7 strangely specific MLB rules and the even stranger stories that inspired them

The latest edition of the MLB rulebook is 284 pages long. Most of those pages are filled with things you know: 60 feet, six inches to home, what happens when a ball clears the fence, what a standard fielder's glove looks like. Some of those pages, however, are filled with pretty weird stuff -- so weird, in fact, that there just has to be a story behind why someone thought to include it in the first place.

Why are there stipulations regarding spectator overflow? Which baseball revolutionary once successfully ran the bases backwards? You have questions, we've got some excellent stories.

Rule 6.04(c): No fielder shall take a position in the batter's line of vision, and with deliberate unsportsmanlike intent, act in a manner to distract the batter. (PENALTY: The offender shall be removed from the game and shall leave the playing field, and, if a balk is made, it shall be nullified.)

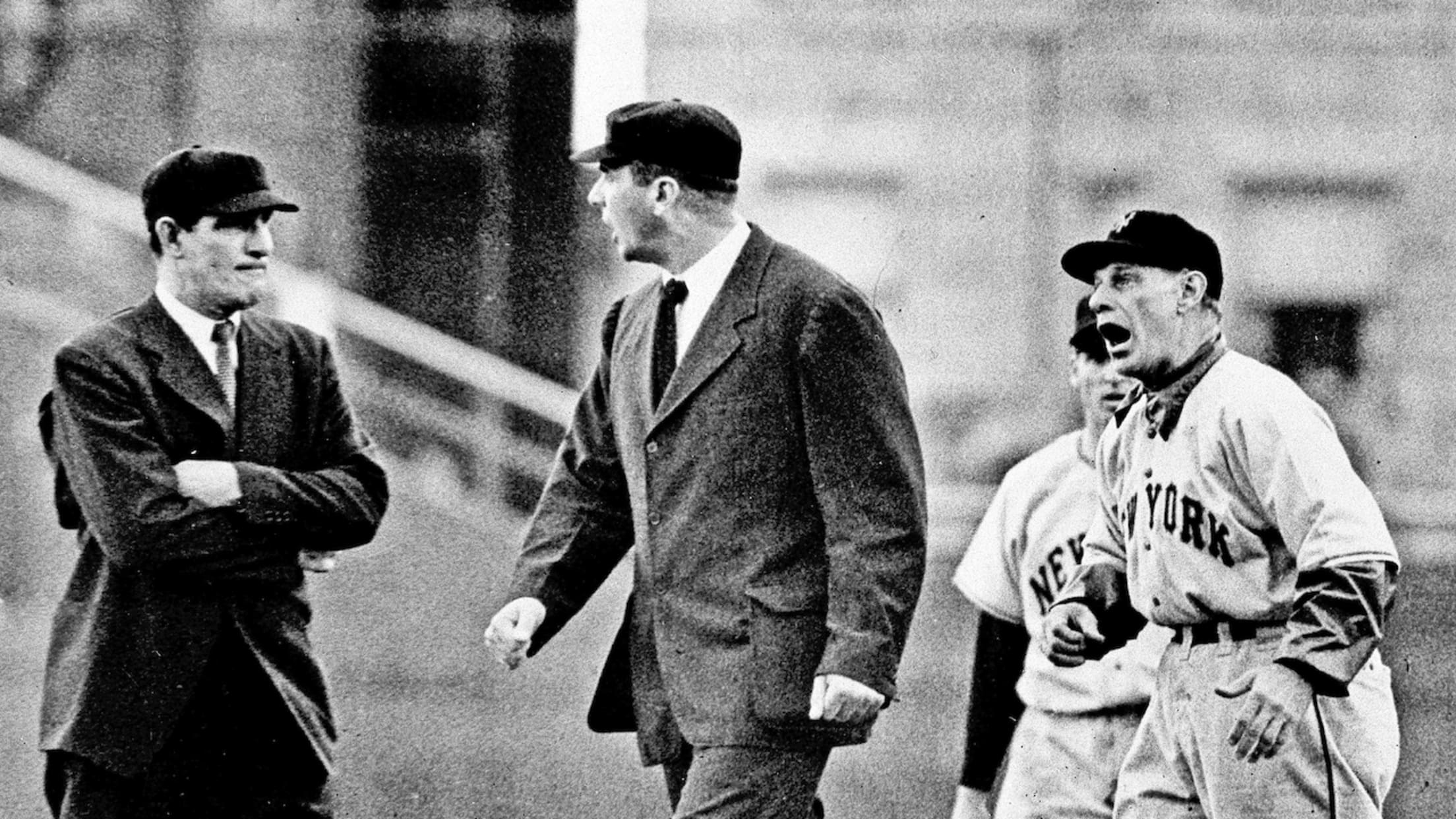

During one of his at-bats against the New York Giants on August 9, 1950, Boston Braves third baseman Bob Elliott requested that the second base umpire shift his positioning slightly -- the ump was in Elliott's line of vision, making it difficult for him to pick up the baseball. Where most would see a simple professional courtesy, however, New York second baseman Eddie Stanky saw an opportunity: Before the next pitch, he strode over to where the umpire had been standing and began doing jumping jacks.

For some reason, Elliott and his teammates were unfazed, and the game passed without incident. Stanky wasn't going to let a little setback spoil his plans, however. Two days later against the Phillies, he was back at it, this time targeting Philadelphia catcher Andy Seminick. Finally, Stanky got the reaction he was looking for -- Seminick was furious, and demanded that the home-plate umpire take action.

There was just one problem: None of the umpires could find a rule preventing it -- somehow, Major League Baseball had lasted for nearly a century without ever having reason to outlaw jumping up and down in a batter's line of sight. In uncharted territory, the umpires allowed Stanky to continue for the rest of the game, hoping to track down National League President Ford Frick afterward to get some clarification.

Frick, however, was nowhere to be found, so the next morning the umpiring crew reached out to Stanky's manager, Leo Durocher, and requested that Stanky cut it out until an official ruling could be made. But Durocher -- befitting the man who literally coined the phrase "nice guys finish last" -- wasn't having it, and told Stanky to recommence with the jumping jacks. "Smart ballplayers have been pulling stuff like that for all the 25 years I've been in baseball," he told the New York Times, "and as far as I'm concerned it's perfectly legal."

Stanky was happy to oblige his skipper and left the umpires no choice but to eject him. That would hardly ease tensions, though: While sliding toward second base later in the game, Seminick took out Stanky's replacement, Bill Rigney, and touched off a benches-clearing brawl that required the NYPD's help to quell. After the game, Frick finally made his ruling, instructing umpires to eject fielders for "antics on the field designed or intended to annoy or disturb the opposing batsman."

Though the language has changed and expanded, the rule has remained on the books ever since. As for Stanky, well, there's a reason his nickname was "The Brat."

Rule 4.05: The manager of the home team shall present to the umpire-in-chief and the opposing manager any ground rules he thinks necessary covering the overflow of spectators upon the playing field, batted or thrown balls into such overflow, or any other contingencies.

These days, it's hard to imagine a situation in which a team would need to come up with ground rules regarding an "overflow of spectators upon the playing field," but as always, we refer you to the cardinal rule: There's a reason this is in the rulebook, and the reason is exactly as weird as you'd expect.

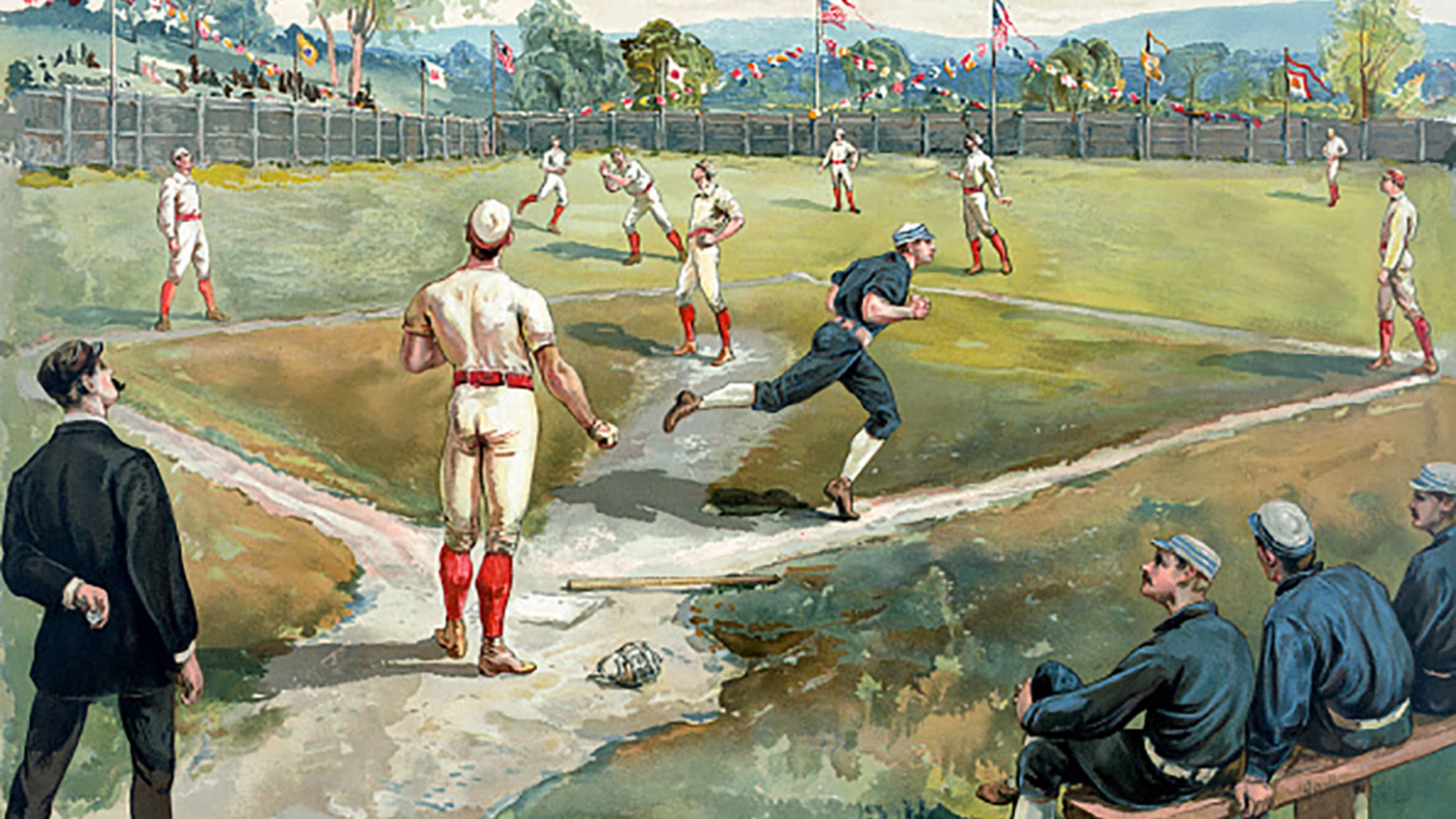

Thanks to the formation of the American League two years prior, the first modern World Series was played in 1903. The matchup featured Honus Wagner and the Pittsburgh Pirates against the upstart Boston Americans -- whose rotation was led by some guy named Cy Young.

As you might imagine, anticipation was high. So high, in fact, that when the Series shifted to Pittsburgh for Game 3, Exhibition Park couldn't fit the entire crowd: The announced attendance was a little over 18,000 fans, but so many more snuck through fences that eventually some 20,000-25,000 had swarmed the field:

The city had to call in over a hundred police officers to handle the crowd, which stood 10 deep in front of the backstop and just a few feet from each foul line by the time the game actually started. Since the spectators clearly weren't going anywhere, ground rules needed to be written, and the responsibility fell on Pirates player/manager Fred Clarke.

Clarke's decision? Any ball that rolled past the outfielders and under the rope separating the field from the fans would be ruled a ground-rule triple. The four games played at Exhibition Park -- the World Series was a best-of-nine until 1905 -- featured 17 ground-rule triples, and Boston rallied from a 3-1 deficit to win the championship in eight games.

Rule 5.09(b)(10): Any runner is out when, after he has acquired legal possession of a base, he runs the bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the defense or making a travesty of the game.

The first thing to know about Herman "Germany" Schaefer is that he was a consummate showman -- the type of guy who would call his own game-winning homer, hit it to that exact spot, then slide into every base on his way home.

That's a story for another time, though. Instead, let's talk about Schaefer's Washington Senators taking on the Chicago White Sox back on August 4, 1911. With teammate Clyde Milan on third as the winning run, Schaefer stood on first base with just one out -- the perfect opportunity to attempt a steal and draw a throw to second base, allowing Milan to score.

Alas, when Schaefer took off, Chicago's catcher hung on to the ball, foiling the plan. Now standing on second, there was nothing for Schaefer to do but sit tight and hope that one of his teammates could come through at the plate ... or, alternatively, to steal first base and try the whole thing again.

Without any hesitation, Schaefer got up and took his lead on the wrong side of the base. Then, on the very next pitch, he sprinted and slid back into first. Probably more baffled than outraged, the White Sox protested to the umpire without calling time -- and in the ensuing commotion, Schaefer got up and started running to second again, this time getting caught in a rundown. Alas, the shenanigans were for nought: Milan attempted to score while the attention was on Schaefer, but the White Sox noticed in time and threw him out at the plate.

Schaefer actually wasn't the first to pull the stunt -- that honor probably belongs to the New York Giants' Fred Tenney -- but he was certainly the last: In 1920, MLB stipulated that any runner who ran the bases in reverse was automatically out. That didn't stop

Rule 6.01(a)(9): It is interference by a batter or a runner when, with a runner on third base, the base coach leaves his box and acts in any manner to draw a throw by a fielder.

In the 19th century, it was commonplace for base coaches to try all sorts of things to distract their opponent, from shouting at opposing fielders to pretending to be baserunners.

The introduction of coaches boxes in 1887 helped curb "the trick of personating runners from third base to home plate," as the New York Times dubbed it, but that didn't stop base coaches from ... getting a little carried away. Case in point: While serving as Brooklyn's third-base coach in 1890, George Smith got so worked up waving a runner in that he decided to run all the way home himself. Understandably confused, the opposing catcher tagged Smith instead of the actual baserunner (though, after a long argument, the umpire did eventually rule the runner out).

Despite seemingly endless compelling evidence to the contrary, baseball didn't make a rule change for several more years -- all base coach interference wasn't explicitly prohibited until 1904.

Rule 6.01(a)(5) Comment: If the batter or a runner continues to advance after he has been put out, he shall not by that act alone be considered as confusing, hindering or impeding the fielders.

Rule 6.01(a)(5) deals with runner's interference, and is pretty straight-forward:

"It is interference by a batter or runner when any batter or runner who has just been put out, or any runner who has just scored, hinders or impedes any following play being made on a runner. Such runner shall be declared out for the interference of his teammate."

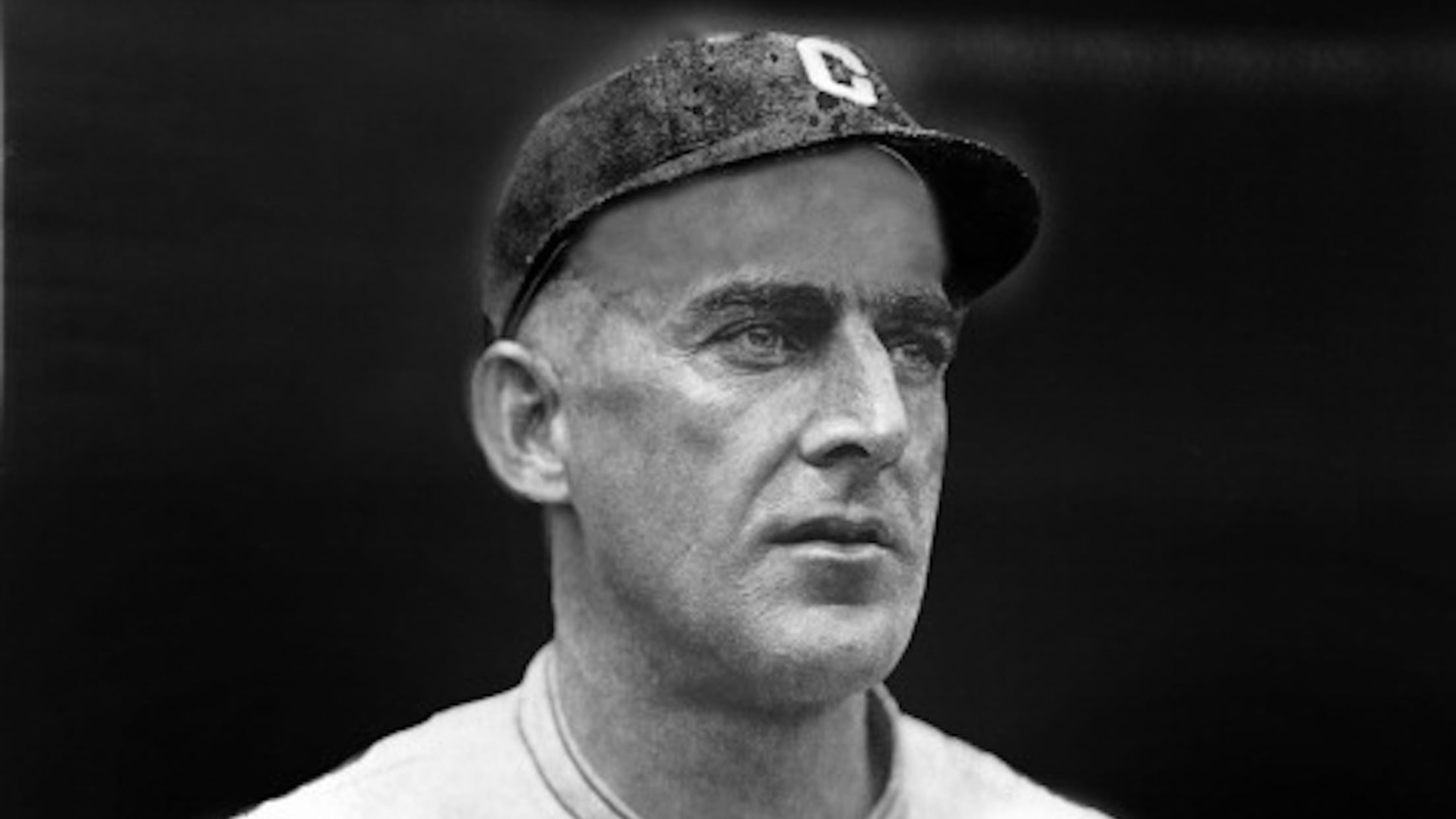

Immediately after that, though, comes the curious comment above, stipulating that if a runner continues to advance after he's already been called out, he may or may not be guilty of interference. If that seems like an oddly specific event to account for in a rulebook, well, you're not wrong: It dates back to 1926, when the Dodgers and Cubs combined for one of the weirdest plays in baseball history.

The Cubs had loaded the bases with just one out in the top of the sixth. With Jimmy Cooney (pictured above) on first,

Maranville's throw back to first was wild, and the Chicago runners were off to the races. Brooklyn pitcher Jesse Barnes finally got to the ball, and as he saw a Cub trying to score he instinctively threw home to his catcher, Mickey O'Neil. O'Neil prepared to make the tag ... only to watch as the runner calmly peeled off and started heading for his dugout: It was Cooney, who despite being called out back at second had kept running as a diversion.

By the time O'Neil realized what had happened, he had followed Cooney halfway to the dugout, and Joe Kelly -- the man who started all this madness by hitting a simple grounder -- was standing on third. Brooklyn protested, but no one could come up with any rule that prohibited the trick, and Chicago would tack on two more runs in the inning.

Wanting to prevent any Cooney-style gamesmanship but also allow for runners who are just trying to stay out of the way, MLB created the provision that exists today, which essentially leaves the matter to the umpire's discretion.

Rule 5.11(a)(2): The Designated Hitter named in the starting lineup must come to bat at least one time, unless the opposing club changes pitchers.

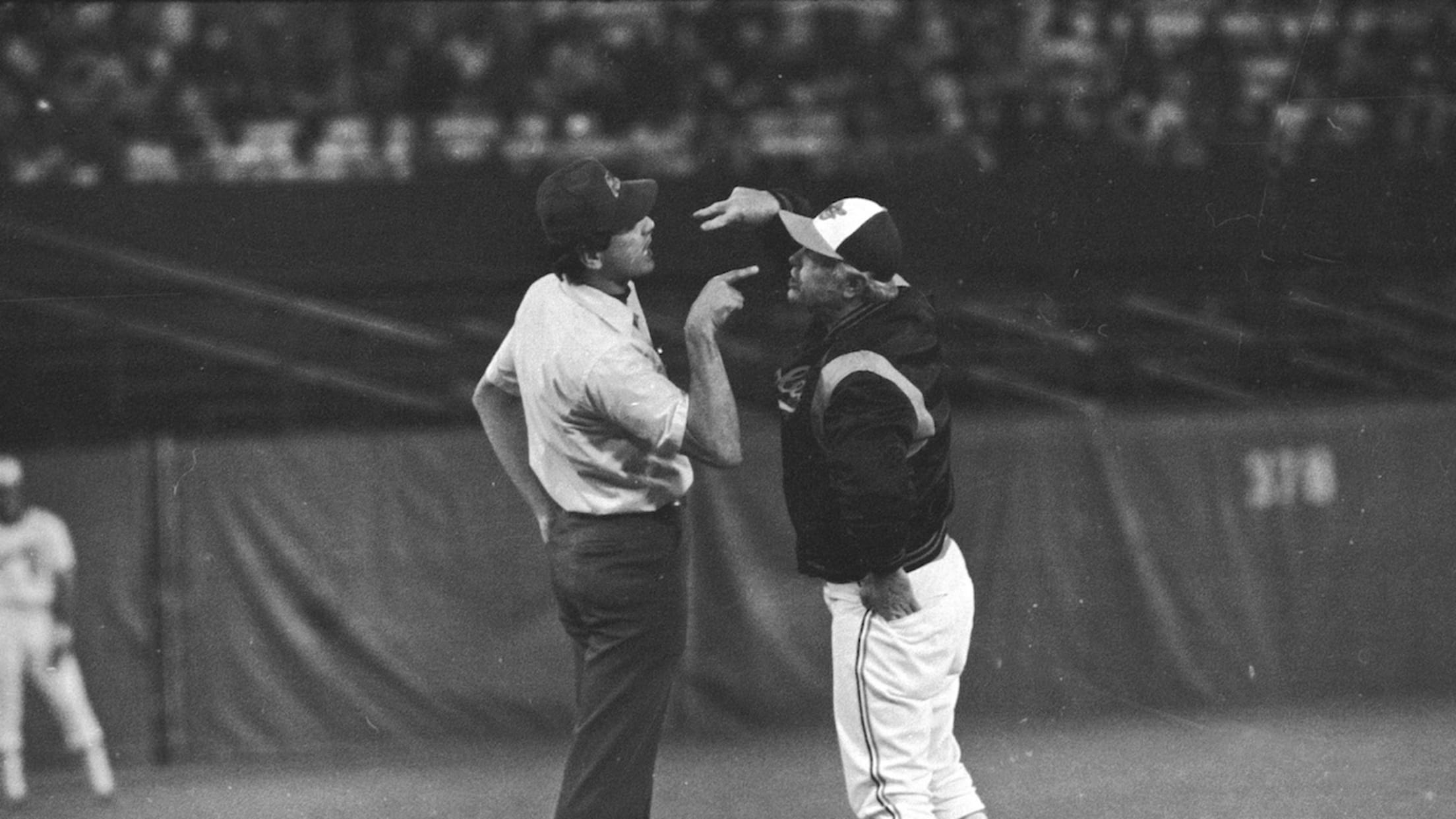

It's only fitting that Earl Weaver would inspire his very own rule -- after all, he once thoroughly ripped up a rulebook in front of an umpire just to make a point.

Sadly, though, the Earl Weaver Rule doesn't involve paper-shredding of any kind. It instead involves the DH, which was established in the American League in 1973 as Weaver was beginning his sixth season as manager of the Orioles. At the time, the new position came with just one stipulation: The designated hitter had to be selected prior to the game and included in the lineup cards presented to the home-plate umpire. Naturally, it didn't take long for Weaver to find himself a loophole.

Rather than simply naming a DH in good faith, Weaver would pencil in a pitcher he had no intention of using that day -- only to send up whichever hitter he actually wanted when that spot in the lineup came around. The move allowed Weaver to choose from his entire bench, picking the ideal batter depending on the game situation.

In 1979 alone, Weaver pulled this trick -- which became known as the "Phantom DH" -- 21 times, 12 of which featured starter Steve Stone. In one of those instances, Stone had already flown ahead to prepare for his start in Toronto. Weaver even named Tippy Martinez as DH one day despite the fact that Martinez was in Colorado for a funeral at the time.

MLB closed the loophole at the end of the 1980 season, stipulating that every designated hitter in the lineup at the start of a game must have at least one at-bat. The rule still exists today, although naming a pitcher as your DH doesn't seem nearly as ridiculous anymore.

Rule 8.01(c): Each umpire has authority to rule on any point not specifically covered in these rules.

Admittedly, this one's cheating: There's no single strange story that inspired Rule 8.01(c), which gives umpires latitude to handle anything unusual that might come their way. Rather, it's the product of decades and decades of them, an entire history of coming up with inventive ways to duck the rules.

Like, for example, when players start trying to use potatoes as decoys. Using peeled, frozen and whitewashed potatoes as baseball doppelgangers was a pretty common trick, and a catcher in the Class D Evangeline League came up with a unique twist on it back in 1934 -- after a pitch, he pulled a potato out of his back pocket and threw it into the outfield.

Thinking it was simply a wild throw, two runners tried to score, only to be tagged out when they discovered that the catcher still had the ball. The umpire -- invoking his powers under 8.01(c) -- ruled the runners safe and refused to accept the catcher's explanation that he had simply found the potato on the ground and was trying to safely remove it from the field of play.

The moral of the story, for both fans and rulebook authors: No matter how many weird things you think you've seen, baseball is always coming up with something new.