Why is a game 9 innings? These are the backstories behind baseball's iconic rules

For decades, baseball has remained such a constant that its rules and structure have become as cherished as its greatest players. The run-scoring environment might have changed a bit since 1905, but the fundamental look and feel of the game hasn't. Legendary sportswriter and Spink Award winner Red Smith, as always, said it best: "Ninety feet between bases is perhaps as close as man has ever come to perfection."

But, while Red certainly had a point, the story behind that perfection was less divine intervention than a whole lot of trial and error. So, how did baseball get here? Why are there four balls and three strikes, anyway? You have questions, we have answers.

Why do pitchers throw overhand?

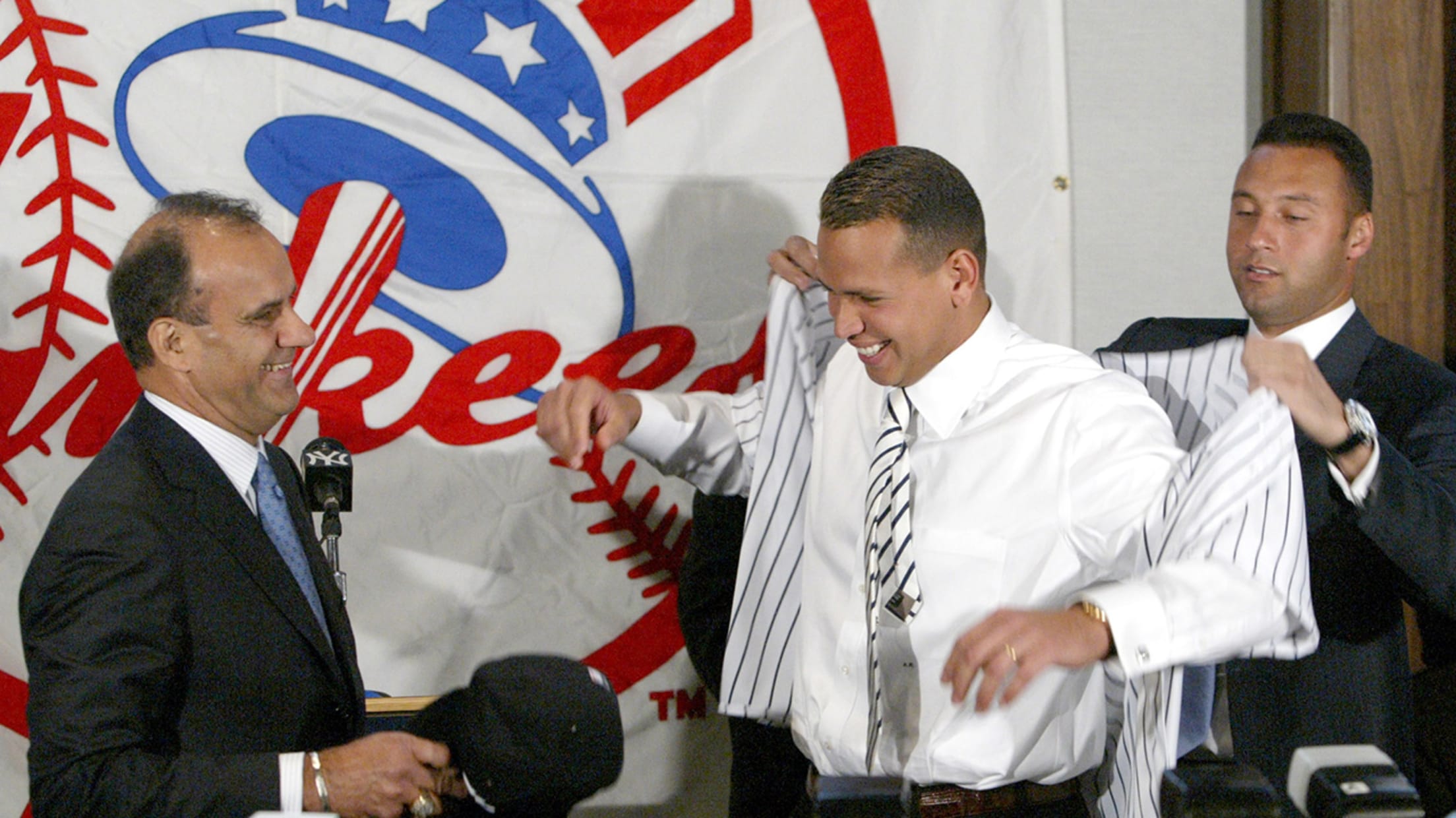

Chad Bradfords of the world aside, baseball history has been written by men throwing overhand. But it wasn't always this way: For decades, every pitcher had to throw with their arm directly perpendicular to the ground, as you can make out in this illustration of a game from the 1860s:

(Incidentally, this is also why they're referred to as "pitchers" -- they pitched the ball in the traditional sense of the term, with a stiff underhanded motion, almost like tossing a horseshoe.)

If that sounds like a pretty easy time for hitters, well, that was the point. Baseball evolved from other stick and ball games like cricket, so, like in those games, pitchers weren't originally intended to be in opposition to the batter. Their purpose was simple: Offer the ball up in a hittable position and get out of the way. Presumably tired of getting shelled year after year, pitchers like Tommy Bond started pushing the envelope inch by inch, creating greater speed and movement with essentially sidearm deliveries -- until, in 1872, the perpendicular rule was relaxed to allow for greater range of motion.

At that point, all bets were off: Pitchers -- recognizing that they could throw harder, locate better and throw more ferocious breaking balls -- began to creep their release point all the way up to a three-quarters arm slot by the early 1880s. Finally, in 1884, Cincinnati Red Stockings boss and "Father of Professional Baseball" Harry Wright made it official: Pitchers could deliver the ball any way they wanted. The move fundamentally changed the relationship to the batter, and changed much of the game with it -- from the rule stipulating that batters could dictate where the pitch was thrown to the function of balls and strikes. Speaking of which ...

Why are batters given four balls and three strikes?

"Three strikes you're out" has been a foundational rule of baseball since the very beginning -- it was even codified in the 1845 Knickerbocker Rules, thought to be some of the very first written rules of the game. For everything else, though, it's been a long and winding road.

Again, baseball's primary objective in the mid-19th century was to let batters put the ball in play as much as possible. So, naturally, those batters were given plenty of chances to make that happen. And we do mean plenty: Initially, called strikes didn't even exist, and when they were instituted in 1858, they came with caveats -- the first pitch couldn't be a called strike, and umpires were required to warn each batter that a certain pitch would be called a strike in the future.

[Game show voice] But that's not all! The idea of a "ball" didn't yet exist, either, so eventually pitchers recognized that they could continue to deliver pitches well wide of the plate and wait for the batter to get impatient. As you might imagine, this created some, uh, pretty drastic pace of play concerns: Batters, free to wait for the perfect pitch, would see up to 40-50 pitches per at-bat -- in one 1860 game between the Brooklyn Atlantics and the Brooklyn Excelsiors, 665 pitches were thrown ... over three innings.

Games were routinely called due to lack of daylight, so, in 1863, called balls were instituted. Even when the concept was introduced, though, it was slowly and tentatively: Only every third "unfair" pitch was called a ball, meaning a batter could only walk after nine (!) pitches outside of the strike zone.

As run-scoring declined and pitchers began to do more than just feed batters, the rule was frequently adjusted -- first to eight balls, then to seven, then to six and so on, until in 1889, the league settled on four.

Why nine innings (and why nine men in a lineup)?

In baseball's infancy, not only was it a game without a clock, but it was also a game without a set number of innings. Instead, teams played until one of them scored 21 aces -- the 19th century equivalent of a run.

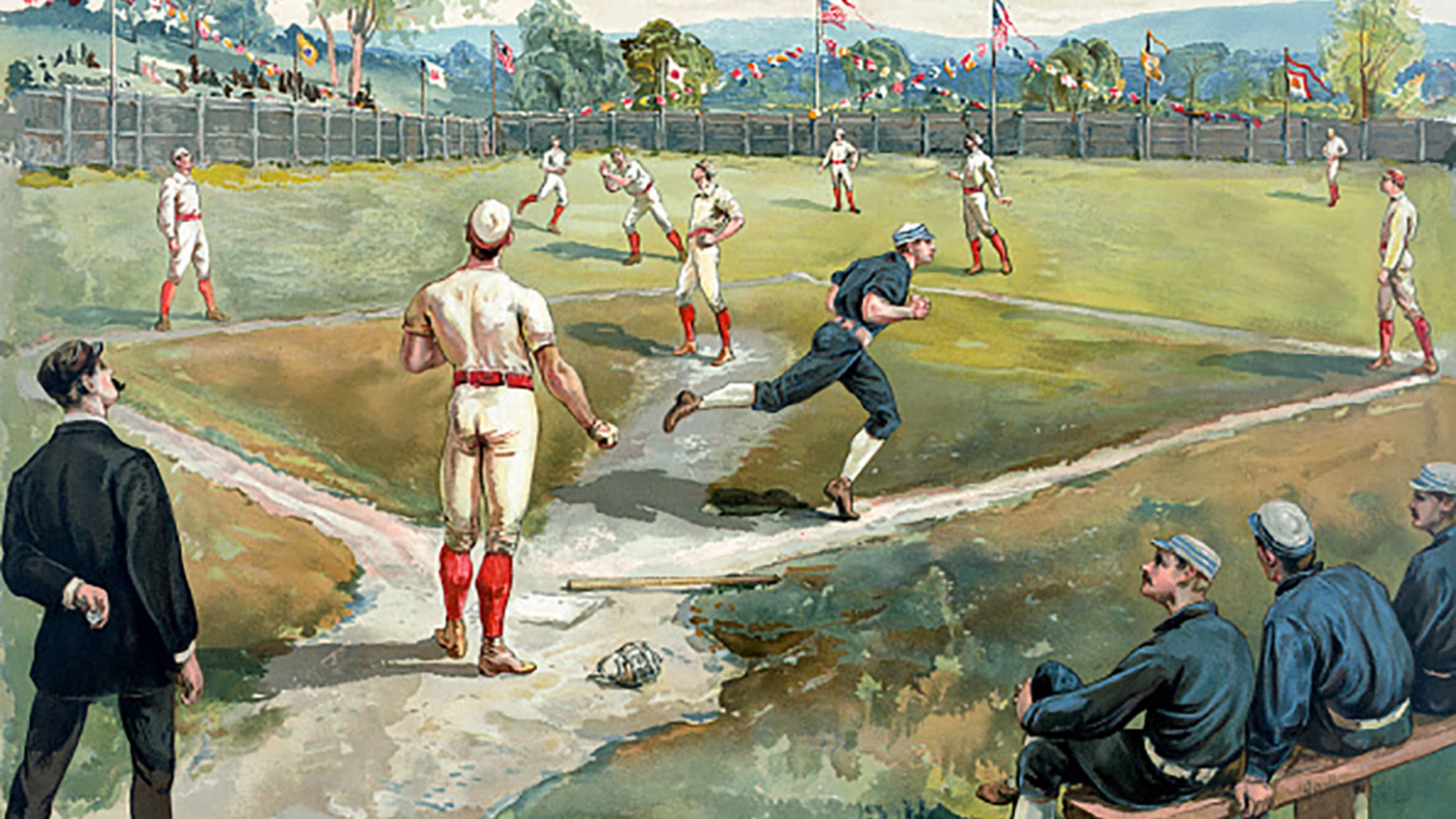

This wasn't a problem at first, in an age in which scoring runs was pretty commonplace -- games lasted an average of only six innings in the 1840s, and featured scores as high as 60-100 combined runs. A problem was brewing, though: As skill levels increased and pitching caught up to hitting, those 21 aces were harder and harder to come by. After an 1856 game ended in a 12-12 tie on account of darkness, it was clear that a change needed to be made. Enter Alexander Cartwright, founder of the Knickerbocker Club and definitely not a real fireman:

That begged the question: Exactly how many innings was the right amount? At that point, the Knickerbockers were torn between seven or nine men to a side -- it all depended on how many were available that day -- and for consistency's sake, the number of players dictated the number of innings played. Alas, this couldn't be decided without some good old-fashioned squabbling. From MLB official historian John Thorn:

In an 1856 Knickerbocker meeting, [two members] backed a motion to permit nonmembers to take part in intramural games if fewer than eighteen Knicks were present ... Duncan F. Curry countermoved that if fourteen Knickerbockers were available, the game should admit no outsiders and be played shorthanded, as had been their practice since 1845.

Sensing that an official ruling was necessary as more and more baseball teams were formed, the Knickerbockers decided to form a committee in 1856 to tackle the issue. The desire for more competitive defense won out, and nine innings -- and nine men -- became the standard for good.

Why 162 games?

Initially, baseball's scheduling was simple: In 1920, the American and National Leagues both had eight teams, and each team would play its league rival 22 times, giving us the 154-game slate that would last for four decades.

And then expansion happened. In 1961, the AL added the Los Angeles Angels and Washington Senators. The next year, the NL welcomed the New York Mets and the Houston Colt .45s. (Yes, this did lead to one year in which the AL's schedule was slightly longer -- they both covered the same number of days, but the NL got more days off.) Suddenly, the simple math was slightly more complicated: Each team playing every other team in the league 22 times would have resulted in an untenable 198-game schedule.

So, MLB cut it to 18 games against each league rival, and 162 games was born. But, while that number has endured, it hasn't been without some controversy as further expansions made the calculation a bit trickier: 76 games within the same division, 66 against non-divisional league opponents and 20 Interleague games. A bit involved? Sure. But, as Thorn explained to Mental Floss back in 2014, good luck changing it: "Baseball is a religion. It becomes the 11th commandment: 162 games."

How did home plate get its shape?

Believe it or not, home plate wasn't always the square-triangle hybrid we know today. Until the turn of the 20th century, games used just about any object teams could find, be it made of metal, marble or even glass. The only thing that mattered was the shape: Home plate had to be circular.

As you may have already guessed, this posed a problem: Imagine sliding into home, only to find your leg scraped or sliced by a piece of rock. (Robert Keating, the man who patented the design for the rubber, even complained that tapping one's bat on home would "jar the batter's hands".) So, in the 1880s, changes were made. The National League mandated a rubber or marble plate in 1885, and in 1887, home plate was transformed into a 12 inch-by-12 inch square -- in line with the other three bases.

This posed difficulties of its own, though -- it was awfully hard to tell whether or not a ball caught the corner when the corner was as small as a single point. The solution? Create a base that was a forward-facing square in the front, to allow for a longer line demarcating the strike zone, while maintaining the diamond look at the back.

Why is it 60 feet, six inches to home?

If you think

For much of the game's early history, the distance from pitcher to home plate was a fuzzy concept -- the Knickerbocker Rules didn't settle on a fixed distance, and by the 1870s, pitchers simply had to stay within a box whose front edge was 45 feet from the front of home plate (again, similar to cricket, though the pitcher wasn't allowed a running start).

This worked for a while ... until pitchers began to move beyond the simple underhand delivery. In 1880, Lee Richmond tossed the first perfect game in Major League history, and John Ward followed up with one of his own just five days later. The two games -- along with the fact that the National League ERA that year was an absurd 2.93 -- sent shockwaves through professional baseball ... and not simply because of Ward's Snidely Whiplash facial hair.

Over the next few years, pitching moved closer to what we know today. Looking to goose offense, the front of the pitcher's box was moved back to 50 feet away, and by 1887 -- with overhand deliveries now the law of the league -- pitchers were required to start their delivery with their feet 55.5 feet from home.

Desperate for some offense with fan attendance on the decline, the Senior Circuit moved the box back one more time. They settled on five more feet -- pushing the pitcher's starting point back to 60 feet, six inches.