U.S. Civil Rights Trail Honors the Jackie Robinson Training Complex

"What Happened Here Changed the World"

(L-R) Roy Campanella; Don Newcombe; Dan Bankhead; Jackie Robinson. Four prominent Dodger players in Major League Baseball history are together for a photo at Historic Dodgertown in the early 1950s. Roy Campanella won three National League Most Valuable Player Awards and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1969; Don Newcombe is the first player to win the National League Rookie of the Year, the Cy Young Award and the National League Most Valuable Player; Dan Bankhead is the first African-American pitcher to make his debut in the Major Leagues; Jackie Robinson one of American history's greatest heroes was a 1949 National League Most Valuable Player and was elected to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 1962.

1945-1946

The Brooklyn Dodgers sign seven of the first nine African-American players to professional baseball contracts. They include Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe. In his autobiography, "Off The Record," former Dodger Vice President Buzzie Bavasi wrote, "Walter (O'Malley) had as much to do with Jackie's (Robinson) reaching the big leagues as did Branch Rickey."

April 15, 1947

Jackie Robinson breaks the color barrier and makes his debut in Major League Baseball on April 15 in a game at Ebbets Field. Dodger President and General Manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson initially to a contract on October 23, 1945 and assigned the former UCLA four-sport star to play for the Montreal Royals in 1946.

In his book, "The American Diamond," Dodger President Branch Rickey wrote, "The ownership of Brooklyn at the first meeting in New York approved Negro employment. That was a new day for ownership in professional baseball and (the board of directors of the Brooklyn Baseball Club) were heartily in favor." In 1947, Dodger ownership consisted of Rickey, Walter O'Malley, John L. Smith and Dearie McKeever Mulvey. It would take more than a decade for all Major League clubs to have an African-American player in a big league game.

August 26, 1947

Dan Bankhead makes his Major League debut with the Dodgers to become the first African-American pitcher in the Major Leagues. Bankhead homered in his first Major League plate appearance.

September 30, 1947

Jackie Robinson becomes the first African-American player to make a World Series appearance. On October 5 in the same World Series, teammate Dan Bankhead is a pinch-runner as the first African-American pitcher in a World Series game.

Robinson wins the first-ever Rookie of the Year Award in 1947 (for both leagues) after batting .297 with a National League-leading 29 stolen bases, an award that would later be named for him. He is inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962 as the first African-American player.

1948

Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida becomes the first and only integrated Major League Baseball Spring Training site in the South.

The Brooklyn Dodgers concluded their Spring Training at Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida with two exhibition games. The Dodgers and their Montreal Royals' minor league club both have African-American players who will be staying in the same living quarters and eating in the same dining room as all other players and personnel. Until the early 1960s, Dodgertown will be the only integrated Spring Training base in Major League Baseball in the South.

March 31, 1948

The Brooklyn Dodgers play the Montreal Royals in an exhibition game at a field near the Vero Beach Airport. It is the first time in Spring Training in the South that a Major League team has African-American players. Jackie Robinson hits a home run in the first inning leading off for the Dodgers as they defeat Montreal, 5-4. Roy Campanella's contract that day is purchased by the Dodgers, making him the third African-American player for the team, the others being Robinson and Dan Bankhead.

An aerial view of Historic Dodgertown, circa the mid 1950s. In the foreground is Field No 1 and Field No 2 to the far left. In the background are the former Naval Air Station barracks that in 1948, for the first time, provided integrated living and dining quarters at a Spring Training site in the South as ordered by the Brooklyn Dodger co-ownership of Branch Rickey, Walter O'Malley, John Smith and Dearie McKeever Mulvey.

April 20, 1948

Roy Campanella becomes the first African-American catcher to play in Major League Baseball. He later became a three-time National League MVP and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969.

October 5, 1949

Pitcher Don Newcombe becomes the first African-American to start a World Series game in Game 1 of the 1949 World Series against the New York Yankees.

October 30, 1950

Walter O'Malley is quoted in a column written by "The Old Scout" and states, "Prejudices have no place in our society and certainly not in sports."

(L-R seated) Mrs. Mary Smith, Brooklyn Dodger co-owner; Harry Hickey, member, Dodger Board of Directors. (L-R standing) Walter O'Malley; Dodger pitcher Joe Black. Walter O'Malley celebrates with pitcher Joe Black at the Dodgers' 1952 National League celebration party at the Hotel Bossert in Brooklyn in September of that year. Black would win the 1952 National League Rookie of the Year and would win Game 1 of the 1952 World Series to be the first African-American pitcher to start and win a World Series game.

October 1, 1952

Joe Black's performance in Spring Training at Dodgertown earned him a spot on the 1952 Dodger Major League roster. He becomes the first African-American pitcher to win a World Series game as a starting pitcher, 4-2 over the New York Yankees in Game 1 at Ebbets Field. Black would be named the 1952 National League Rookie of the Year for his pitching.

A color aerial view of Historic Dodgertown showing Holman Stadium and the heart-shaped lake by the ballpark. The lake in its shape was a tribute from Walter O'Malley to his wife, Kay. In 1962, despite the presence of Southern "Jim Crow" laws, Walter and Peter O'Malley made seating integrated allowing any baseball fan to sit wherever they pleased at Dodgertown.

1954

Dodger President Walter O'Malley privately builds a pitch-and- putt nine hole course by the heart-shaped lake on the Dodgertown base to provide recreation to all players. The golf courses in the city were private and not integrated.

July 17, 1954

For the first time in Major League Baseball history, the majority of the Dodgers' lineup are minorities with Jackie Robinson (3B), Jim Gilliam (2B), Sandy Amoros (LF), Roy Campanella (C) and Don Newcombe (P) starting the game against Milwaukee, won by the Dodgers at County Stadium, 2-1. All five players were originally signed by the Dodgers, and earned their spot on the Major League roster because of their Spring Training play that season at Dodgertown.

December 22, 1954

The Brooklyn Dodgers will not play an exhibition game in Birmingham, Alabama. The Sporting Newscontains a news item that "The Brooklyn (Dodgers) club has adhered to its policy of playing no games where any or all of its players cannot participate."

February 8, 1955

Jackie Robinson, interviewed in Look magazine said Walter O'Malley told him "The club (Dodgers) wouldn't hesitate to put nine Negroes on the field if they were the best nine available players."

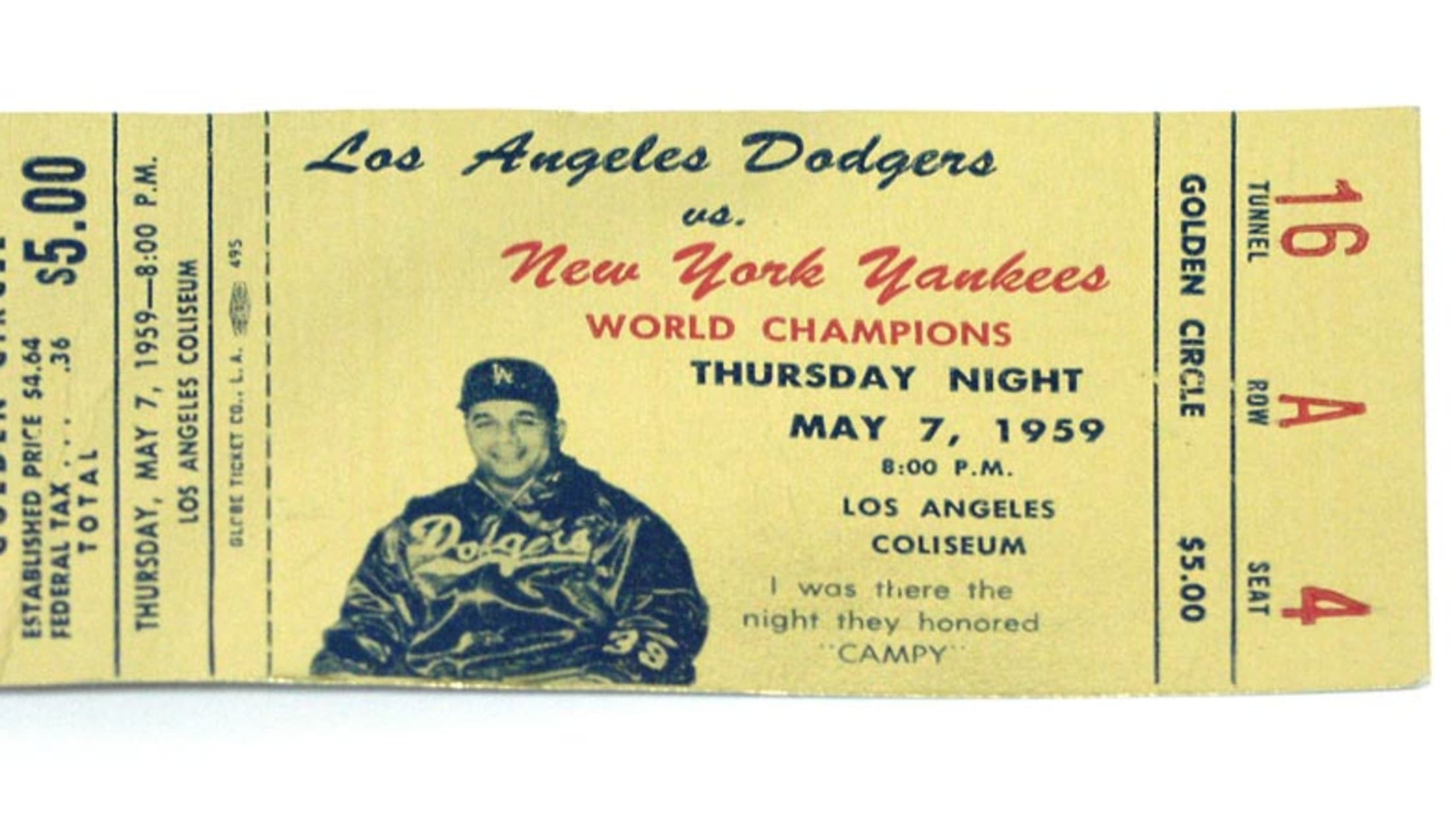

This gold ticket is for the May 7, 1959 tribute game to Roy Campanella to honor the three-time National League Most Valuable Player. Campanella, one of the Dodgers' greatest ever players, was a regular visitor to Dodgertown after his career ended. He had a regular place at Historic Dodgertown where he would sit and talk to anyone after a day of workouts. And at this location, there is still a sign, "Campy's Bullpen."

May 7, 1959

A then record Major League Baseball crowd of 93,103 fills the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for an exhibition game with the New York Yankees to recognize Roy Campanella who retired from playing baseball because of injuries suffered in a single car accident. All the net proceeds of the Dodgers' share are provided to the care of Campanella. Campanella would become a regular fixture in the Dodgers' Spring Training at Dodgertown on invitations from Walter and Peter O'Malley to instruct a new generation of catchers that included John Roseboro, Steve Yeager, Mike Scioscia and Mike Piazza. At Historic Dodgertown, "Campy's Bullpen," his favorite place to unwind and tell stories after a day of Spring Training workouts as a player, is still featured by a sign in its original spot.

October 6, 1959

The Los Angeles Dodgers defeat the Chicago White Sox in six games to win the 1959 World Championship. It is the first time in Major League Baseball history a team has four African-American players on the field for the final out of the last game. On the field in the ninth inning are third baseman Jim Gilliam, second baseman Charlie Neal, shortstop Maury Wills, and catcher John Roseboro. All four players were originally signed by the Dodgers and developed in their minor league system, including Spring Trainings at Dodgertown.

November 1, 1959

Mallie Robinson, mother of Jackie Robinson, writes to Norris Poulson, the Mayor of Los Angeles that "Mr. (Walter) O'Malley, as owner of the Dodgers, gave my son, Jackie, a chance to break the color line in baseball."

August 8, 1961

Dodger President Walter O'Malley wrote a letter to Frank Scott and Robert Cannon of the Major League Players' Association regarding their inquiries of segregation in the South in Spring Training. O'Malley responded, "There are local city (of Vero Beach) ordinances that are not in keeping with our thinking, which, however, cover situations off our self-contained base. Our relations with the local political administration are not cordial at the moment and we have been giving some thought to transferring our base to the West Coast unless we see signs of improvement."

1961

Dodger Vice President Buzzie Bavasi stated in Jet Magazine on segregated seating in Spring Training stadiums, "When we (the Dodgers) sell tickets (for Spring Training exhibition games), the law requires separate sections. We have to comply with the law."

1962

Dodgertown Director Peter O'Malley completely removes the concept of segregated seating, water fountains and bathrooms in Holman Stadium at Dodgertown, despite the prohibition of laws in the South. Columnist Larry Reisman in the TC Palm newspaper wrote March 4, 2010, "The O'Malley family who owned the team who were so instrumental in ending the color barrier in Major League Baseball, helped set an example by integrating the stadium (Holman Stadium in Dodgertown). Schools were finally integrated in 1969."

April 11, 1962

Columnist Melvin Durslag writes in The Sporting News, "Where seating in the baseball stadium (Holman Stadium) has always been segregated, Walter O'Malley removed the signs this year, inviting Negroes to sit anywhere in the park. Perhaps 99 per cent continue to occupy the old Jim Crow seats, but slowly, more are expected to make the shift. In town, O'Malley's popularity hasn't thickened."

March 31, 1965

Jackie Robinson returns to Dodgertown and again makes sports history by being the first African-American to do sports commentary on national television. ABC-TV signed Robinson to provide background on telecasts with announcer Chris Schenkel and the pair combined to do a simulated telecast in an exhibition game at Holman Stadium featuring the Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals.

April 4, 1965

At Dodgertown before the start of the regular season, Maury Wills is named "Captain" of the Los Angeles Dodgers to become the team's first African-American captain. With the distinction, Wills becomes the second African-American team captain in Major League Baseball history after Willie Mays of the San Francisco Giants.

1965

The Los Angeles Dodgers are the first team in Major League Baseball history to have two minorities on the Major League coaching staff with African-American player Jim Gilliam and Preston Gomez from Cuba. Gilliam and Gomez are on the coaching lines at Holman Stadium in Dodgertown to begin their tenure.

1965

A true nine-hole golf course on Dodgertown property is open to the public, the first public golf course in Vero Beach, Florida. African-American Dodger players were not invited to play at the golf courses in the town because they were private and not integrated. Walter O'Malley wanted all his players to have the opportunity to relax after daily workouts by playing golf on the public course he privately built just beyond Holman Stadium at Dodgertown.

April 23, 1974

National Baseball Hall of Fame sportswriter honoree Sam Lacy wrote in the Baltimore Afro-American on segregation issues in Spring Training in the South, "Something had to be done to eliminate these problems (hotel management refusing to provide rooms for blacks) and bring about the all-for-one residency at the same time….Given the assurance that the Dodgers would assume complete responsibility for policing the area, the Vero Beach government promised to keep hands off until called in by the ball club. In that way, (Dodger President and General Manager Branch) Rickey and his associates were able to skirt the local ordinance requiring Jim Crow housing. It was, without a doubt, the first crack in the wall of prejudice that continued to plague baseball for the next 15 years."

Walter O'Malley continued to break ground in advancing the enjoyment of African-American players at Dodgertown. In this aerial photo of Historic Dodgertown, the foreground shows part of the nine-hole golf course O'Malley built on the base property so African-American players could have a chance to have recreation after the training day. Dodgertown Golf Course was the first public golf course in Vero Beach and was open to anyone who wished to play.

1977

In his book, "Baseball's Great Experiment", author Jules Tygiel wrote, "To allow black players to avoid Vero Beach's Jim Crow system, team officials at Dodgertown showed movies, built a nine-hole golf course for the players and had an airstrip that could provide transportation in and out of the facility."

August 16, 1979

The Los Angeles Sentinel newspaper wrote on the passing of Walter O'Malley, "O'Malley was a family man who dominated the game of baseball for thirty-five years and, along with Branch Rickey, gave black players their first real crack at the major league. O'Malley will long be remembered by players of color for his very unique style of courage and for his warm humanity….He went to bat for black players when it was unpopular and he improved the game of baseball by his daring actions."

September, 1980

Dodger Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella is asked in a question and answer session with Sepia Magazine,

SEPIA: "You brought up the name of Walter O'Malley earlier. Was he as much involved with the integration of major league baseball as Branch Rickey?

Campanella answered: "Definitely. When we went to Spring Training in 1948, Mr. O'Malley started Dodgertown, which was formerly the Vero Beach Naval Air Station. He had it set up so that we could eat together and we could sleep together, but we couldn't play golf with our teammates after practice. He (O'Malley) took care of that developing a nine-hole golf course and we also ended up having an 18-hole golf course if we wanted to play."

February 21, 1988

Tom Moczydlowski of the Vero Beach Press Journal wrote of the integration of Holman Stadium for Dodger exhibition games as narrated by Ralph Lundy, a free-lance writer who wrote for the Negro News Section of the Jacksonville Journal and a member of a biracial committee in Indian River County. "Lundy went to the (1962) meeting (with Dodgertown Director Peter O'Malley) with Rev. Dr. Arnold Wettstein of the Community Church, the president of the biracial committee. They didn't have to talk long to O'Malley before their ideas were approved to end segregation at Holman Stadium. 'He was very receptive and understood the problem. He knew what we were asking." Modzydlowski continued, "Within two days, the "colored" and "white" signs that hung above water coolers and restrooms were removed. The black section of the stadium-the bleachers between third base and outfield - became like another other (sic) seats and the blacks were allowed to sit anywhere they chose."

February 23, 1998

The Vero Beach Press Journal had an article written by James Kirley on the integration of Holman Stadium. "Peter O'Malley who had just been appointed director of Dodgertown (in 1962) remembered signs over Holman Stadium restrooms stating they were for use by blacks." O'Malley said, "We all agreed that had to go immediately…….I said, 'That's crazy! They can sit wherever they want!'"

(L-R) Don Drysdale; Tommy Davis; Sandy Koufax; Maury Wills. These four Dodgers were performance leaders for the Dodgers' great play from 1959 to 1965 where they won three World Championships in 1959, 1963, and 1965. In 1962, Drysdale won the Cy Young Award, Tommy Davis was the National League batting champion, and Maury Wills won the 1962 National League Most Valuable Player Award. In 1963, these four players were part of the 1963 World Champion Dodger team that swept the New York Yankees in four games. In 2005, Tommy Davis stated in an autobiographical book, "Tales from the Dodger Dugout," that he signed a professional contract with the Dodgers because Jackie Robinson called Davis and gave him his strongest recommendation the Dodgers would the best team for Davis to play.

2005

Former Dodger outfielder Tommy Davis writes in a book, "Tales From the Dodger Dugout," how he came to sign a minor league contract with the Dodgers in 1956 when he was a heavily sought after free agent because of a phone call from Jackie Robinson. "When he (Robinson) called, he said, 'This is Jackie Robinson. I'd like to talk to you about the advantages of signing with the Dodgers, what to look forward to. They treat me good and under the circumstances, they're going to look after you." Tommy Davis was a two-time National League batting champion in 1962 and 1963 and was a member of the Dodger World Championship teams in 1963 and 1965.

March 9, 2008

Columnist Richard Griffin wrote, "The reality of the Dodgers' move, removing themselves from reliance on any local Florida community in order to run their own mini-city (mayor and all) for the spring is far more compelling than convenience. It is linked to conflict and the unfolding history of American civil rights…and wrongs. The history of Dodgertown parallels and reflect (Jackie) Robinson and (Branch) Rickey's pioneer work in the great, social experiment of integration."

March 17, 2008

Historian Timothy Gay wrote in the Boston Globe, "(Dodgertown) revolutionized the social structure of baseball, and in a lesser degree, the nation."

February 24, 2009

Charles Fountain wrote for the website "Boston.com" and had this to say of Dodgertown, "And history was made here. And not just baseball history. Branch Rickey brought spring training to this abandoned naval air station in 1948 because the old barracks would be under the control of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and thus free of the local segregation ordinances that blocked the mingling of the races in hotels and restaurants throughout Florida until the 1960s. At Dodgertown, the Dodgers could be a team on and off the field. How much of the integrated team's considerable on-field success during the 1950s may have been born of that? 'It brought the team together, there's no question about that," said (Peter) O'Malley of the Dodgertown intimacy, "and at the most important time of the year.'"

March 13, 2009

Author Charles Fountain was interviewed by News@Northwestern, a Boston university website and said of Dodgertown, "That meant all the Dodger players, black and white (could be housed). Florida was segregated at the time and the Dodgers were the only team that lived together as a team, until the segregation customs and ordinances were struck down in the early 1960s. That makes Dodgertown and Vero Beach historic for reasons that have nothing to do with baseball."

April, 2010

Jeff Idelson, President of the National Baseball Hall of Fame wrote in "Memories and Dreams" the monthly magazine of the Hall of Fame, "We need to thank Dodgers' owner Walter O'Malley for his open-mindedness (in signing Jackie Robinson). When you are next in Cooperstown, stop by his and Branch Rickey's plaques and remember their brilliance in signing (Jackie) Robinson."

November 10, 2014

In dedication ceremonies, Historic Dodgertown is named a "Florida Heritage Landmark" and a Florida Historical Marker is established by the conference center. The marker displays the history of Dodgertown as a Spring Training site in Florida and the language on the sign states "Dodgertown was the South's first racially integrated spring training camp."

February 15, 2015

Historian Michael Beschloss wrote in the New York Times, "The (Dodgertown) camp, with its own barracks and dining halls, would liberate the team from Jim Crow…..But Dodgertown itself could not solve the larger problem of racial segregation in the Grapefruit League. More than a decade after (Jackie) Robinson joined the Dodgers, black players for other teams were still shunned by many Florida hotels and restaurants."

February 19, 2015

American History Professor at Lawrence (Wisconsin) University, Jerald Podair, Ph.D writes an essay titled "Haven of Tolerance" for the importance of Dodgertown and the integration of Major League Baseball in Spring Training. "But Dodgertown was more than just an incubator of talent. Its significance extends beyond the playing field into the social and racial history of Florida, the South, and America as a whole. By offering an integrated and egalitarian workplace, one in which players were judged not by who they were but what they did, Dodgertown was unique not just among Southern Spring Training facilities, but among Southern institutions generally."

2015

In the book "The Black Press and Black Baseball, 1915-1955, author Brian Carroll with Ratuken Kobo, researched the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper that quoted one Dodger player saying of Dodgertown, "The only segregation in Dodgertown existed by ability, not color."

2016

Author Michael Leahy wrote in his book, "The Last Innocents" of the Los Angeles Dodger teams in the decade of the 1960s, "It had become part of the franchise's lore that the Dodgers had done more to advance the cause of racial opportunity than any other team in professional sports. In addition to (Jackie) Robinson, (Roy) Campanella, and (Don) Newcombe, the Dodgers' prominent African American signings had included pitcher Joe Black, infielders Jim Gilliam and Charlie Neal, outfielder Sandy Amoros, and catcher John Roseboro. Some major-league clubs in the 1950s still had yet to sign their first black player."

2016

Continuing in the book, "The Last Innocents," author Michael Leahy wrote, "Led by an indignant Tommy Davis, a group that included (John) Roseboro, (Jim) Gilliam, (Maury) Wills, and (Willie) Davis, went to Peter O'Malley (Director of Dodgertown and son of Dodger President Walter O'Malley) and demanded an end to segregation in the Vero Beach ballpark (Holman Stadium) which had largely limited blacks to sitting in the right-field corner and in a small area by the left-field foul pole. The shame of the segregated bathrooms, segregated drinking fountains, and separate entrances into the ballpark compounded the wrong, the players added. Holman Stadium was part of Dodgertown and Dodgertown was not the South, they told the younger O'Malley…..Well into the next century, Peter O'Malley would remember the moment. 'Tommy (Davis) pointed out things we were negligent on,'" he recalls. "He was eloquent. And I knew he was right."

2016

Author Michael Leahy in "The Last Innocents," "What (Tommy) Davis didn't know at that moment was the extent to which the young O'Malley had already plunged himself into desegregating the ballpark…..By the time (Tommy) Davis finished speaking to him, (Peter) O'Malley had pledged full support. When the team arrived at the ballpark for the next game, a couple of days later, (Tommy) Davis discovered that segregated bathrooms had been integrated. A Dodger employee, operating on orders from the junior O'Malley, had painted over the word Colored everywhere he could find it in the stadium…….(Tommy) Davis thought in that moment that the victory was complete. What he (Davis) didn't know was that the O'Malley family had acted unilaterally, without the approval of Vero Beach officials. The strict segregation ordinance of the town remained on the books, if Vero Beach wished to enforce it."

2016

Author Michael Leahy in "The Last Innocents," wrote "At any time, Vero Beach officials could have charged the Dodgers with being in violation of its segregation ordinance. They didn't. Making no fuss, the officials quietly rolled over. By then, the Dodgers' enormous economic impact on the city had made the team's presence critical to Vero Beach's welfare. The ordinance died in time from disuse." The Dodgers' black players had realized a victory uncommon to that point in the civil rights movement."

January 19, 2019

The U.S. Civil Rights Trail honors Historic Dodgertown to be a selection as part of their dedication to providing information of the history of American civil rights. The U.S. Civil Rights Trail slogan is "What happened here changed the world," and highlights remarkable places in the United States where significant realization of civil rights were made. Historic Dodgertown is the first fully integrated Spring Training team headquarters in the South for Major League Baseball and actions by the Dodgers there led the way for all professional sports.