The celebration of the Negro Leagues' 100th anniversary has arrived at a poignant time, amid the renewed efforts of many Americans to address racial inequality.

"The social unrest that we've witnessed recently has led many to turn to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum as a thought-leader," said Bob Kendrick, the museum's president. "They've embraced that we are a social justice and civil rights museum. It's just seen through the lens of baseball."

The centennial also brings an important reminder for today's baseball fans: While MLB has worked to internationalize the sport in recent decades, the Negro Leagues must be credited with some of the game's earliest -- and most courageous -- global endeavors.

Because of the discrimination they faced in the U.S., Black players had little choice but to travel in order to find places where they could earn a living while playing the game they loved. Often, those destinations were outside the United States -- including Canada, Japan and nations throughout Latin America.

"Barnstorming always was part of the Negro Leagues' story, more so than it was with the Major Leagues," Kendrick said. "Because of that, the first experience many foreign countries had with American baseball was through the Negro League players. Our game is global now, and a big part of that reason is because of the Negro Leagues."

The 1934 trip to Japan by a team of future Hall of Famers -- including Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx -- is recognized as a seminal moment that sparked Japan's interest in developing its own professional league.

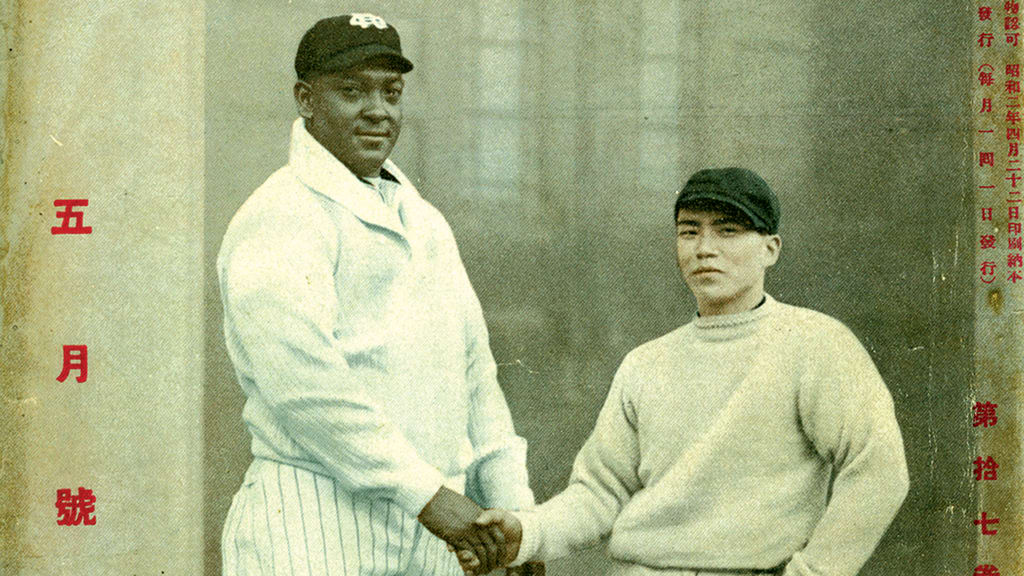

However, the Philadelphia Royal Giants made a similar barnstorming trip to Japan seven years earlier, going 23-0-1 in 24 games against Japanese clubs. It's been said that even the tie was disputed.

The Royal Giants' roster included two members of the Baseball Hall of Fame: catcher Biz Mackey and left-hander Andy Cooper. Mackey is regarded by some historians as the greatest defensive catcher ever; he was known for mentoring a young Roy Campanella with the Baltimore Elite Giants.

"[The Negro Leaguers] treated the Japanese players with great respect," Kendrick said. "They didn't try to run the score up. They taught them the game, and as a result, the Japanese players and fans fell in love with them. ... Many credit the Negro Leagues for sparking the heightened popularity of professional baseball in Japan that has occurred through the years."

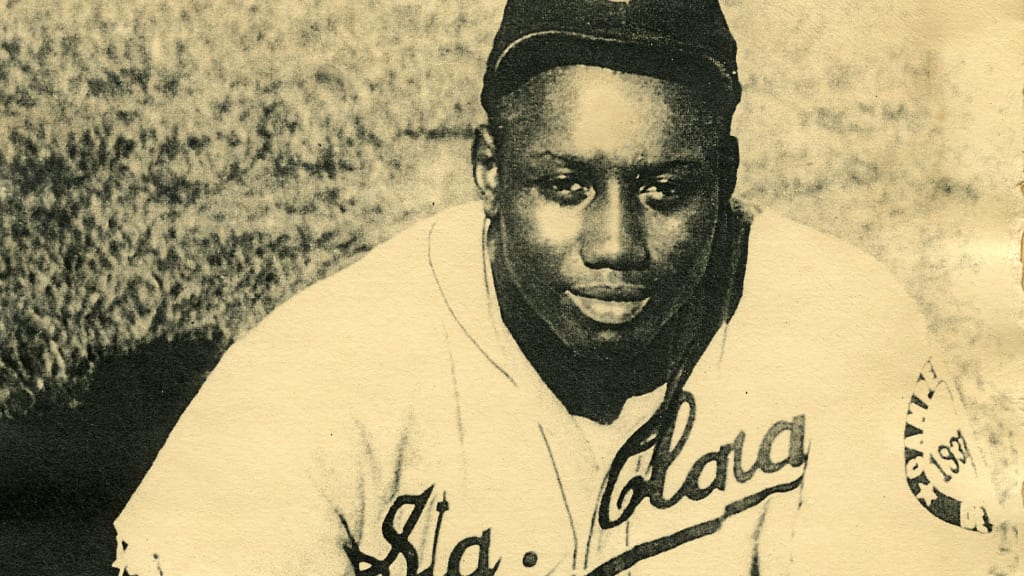

Similarly, the Negro Leagues had an extraordinary effect on Latin American baseball culture. Oscar Charleston, viewed by many historians as one of the greatest all-around players ever, was revered in Cuba thanks to his years of playing winter ball there. In fact, Kendrick said many of the Charleston images and scrapbook artifacts at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum came from Cuba.

"You had to leave your own country to find acceptance," Kendrick said. "The players were treated better in other parts of the globe than they were at home."

Mexican businessman Jorge Pasquel is an essential figure in any comprehensive examination of baseball's integration. As president of the Mexican League and team owner, he recruited Major League and Negro League players with lucrative offers prior to Jackie Robinson breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier.

In an attempt to counter Pasquel's ambition, then-MLB Commissioner Happy Chandler enacted a rule in 1946 to prevent players from returning to MLB after signing with Mexican League clubs. (The initial ban was five years, although Chandler granted amnesty in June '49.) Pasquel's outsized personality -- he was called the "George Steinbrenner of Mexico" -- was chronicled by author John Virtue in "South of the Color Barrier: How Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League Pushed Baseball Toward Racial Integration."

"He signed Black players, paid us good salaries and didn't stand for any segregation," Hall of Famer Monte Irvin wrote in the book's foreword. "That proved that Black players and white players could play together as teammates. I don't think that Jorge gets as much recognition from baseball as he deserves for his contributions toward eradicating baseball's color line."

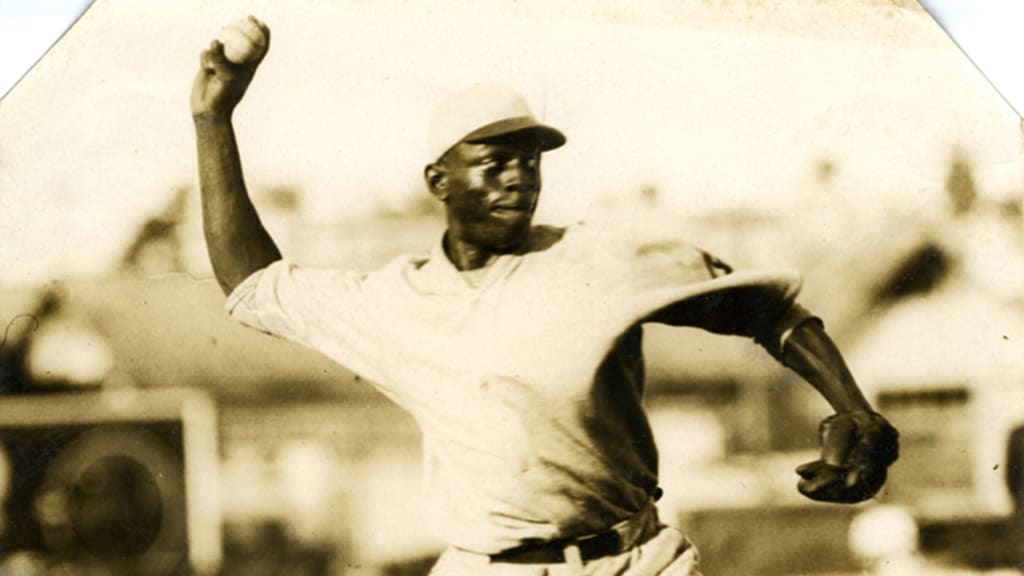

Mexican baseball journalist Paola Ríos has confirmed that Satchel Paige was among the first African Americans to play in the Mexican League in 1938 -- nearly a full decade before Robinson's debut with the Dodgers. Along with Paige, Irvin and Campanella, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell were among the Negro League legends to play in Mexico from the late 1930s through the '40s.

"It was the first time in my life that I felt free," Irvin wrote. "We could go anywhere we wanted, eat anywhere we wanted, do anything we wanted and not have to worry about anything. We just had a wonderful time and I owe that experience to Jorge Pasquel."

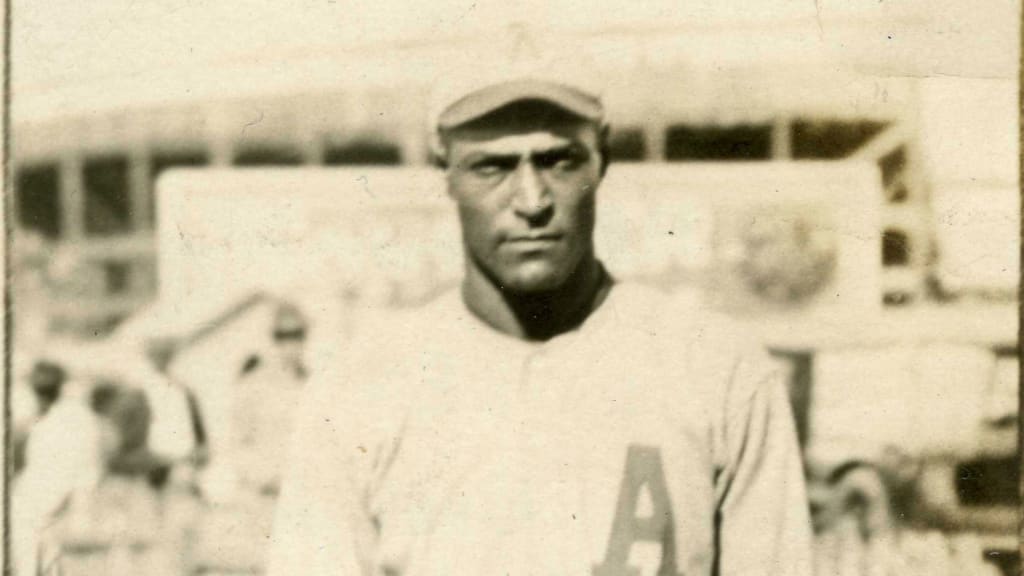

The Mexican League of that era also featured one of the most singular talents in baseball history: the brilliant pitcher/infielder/outfielder Martín Dihigo. According to Virtue, Dihigo is the only player ever elected to the Cuban, Mexican and Venezuelan baseball halls of fame, in addition to Cooperstown.

Although white Cubans played in the Major Leagues prior to 1947, Black Cubans -- such as Dihigo -- were barred in a manner similar to African Americans. Thus, Dihigo starred for many seasons in the Negro Leagues, while often playing in Cuba or Mexico during the winter. Hall of Famer Buck Leonard was said to describe Dihigo as "the best ballplayer of all time, Black or white."

A team known as the Cuban Giants, established in the Northeast near the start of the 20th century, was the first widely known Black professional baseball team in the U.S., according to author and historian Gary Ashwill. (The players were African American, not Cuban, but the name was chosen for marketing purposes.) In 1900, the Cuban X-Giants -- successors to the original club -- became the first team of African Americans to play a confirmed game in Cuba, Ashwill said.

"This would become a regular tradition, with African American teams traveling annually to Havana for fall series against Cuban League teams," Ashwill added. "Starting in the [winter of 1906-07], African American players were signed to play in the Cuban Winter League."

Negro League players also witnessed one of the more troubled chapters in the long history of baseball in the Dominican Republic. Rafael Trujillo, the dictator who ruled the country for more than three decades, sent an intermediary to enjoin Paige, Gibson and Bell to play for his team, Los Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo, in 1937. (Trujillo had renamed the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, after himself.) The Negro League stars helped Trujillo's team win the championship -- while feeling the pressure of armed soldiers positioned around the ballpark, Paige later said.

Canada's role in Major League Baseball's integration is well-known, most notably through Robinson's 1946 season with the Montreal Royals. Robinson's daughter, Sharon, has said how much her parents enjoyed the warmth and friendliness of Canadians they encountered that summer.

Quebec has another claim in shaping 20th century baseball history: In 1922, an African American named Charlie Culver played in six games for Montreal of the affiliated Eastern Canada League, according to Quebec baseball historian Christian Trudeau.

Decades after Culver's stint in Montreal, many former Negro League players arrived in Canada, said Andrew North of the Centre for Canadian Baseball Research, as MLB's integration brought about the gradual end of the Negro Leagues.

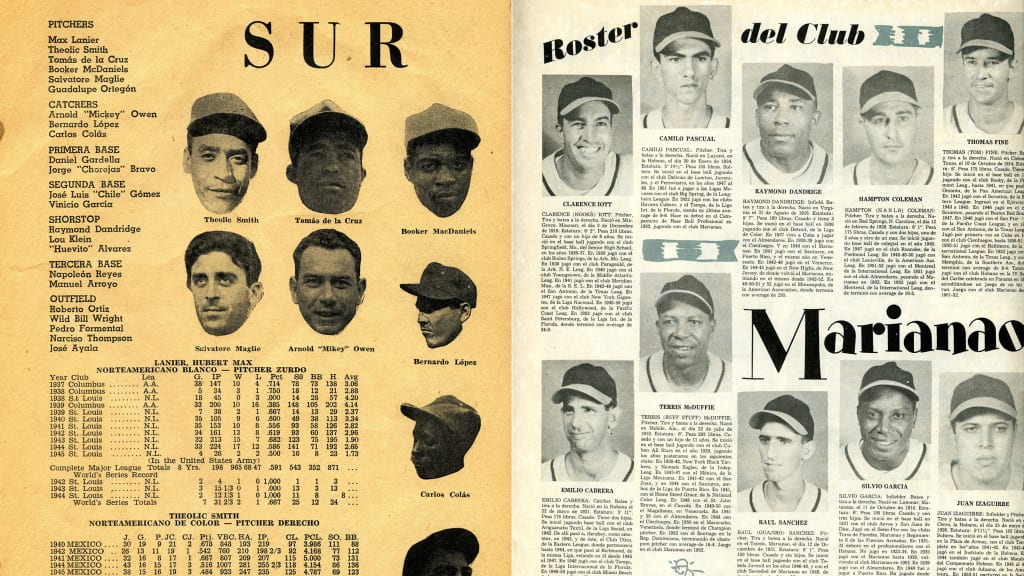

According to baseball historian James A. Riley, the Manitoba-Dakota League -- based in Manitoba and North Dakota -- featured four former Negro League players now enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame: Willard Brown, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day and Willie Wells Sr.

Trudeau's research has concluded that at least 98 former Negro League players appeared in the Quebec Provincial League. Sam Bankhead was a player-manager for the league's Farnham Pirates in 1951, thus becoming the first Black manager or coach in affiliated Minor League Baseball. (Bankhead's brother, Dan, was the first African American pitcher in MLB history, having debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers a little more than four months after Robinson in '47.)

In a research article for SABR, Charles F. Faber wrote that famed Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson formed the Satchel Paige All-Stars and brought the team on a barnstorming tour that included stops in Canada. Perhaps no player exemplified the itinerant lifestyle of the Negro Leagues better than Paige. Above all, Paige and his peers must be celebrated as ambassadors for the game, as their grace and perseverance in the face of discrimination have left a global legacy for the game they loved.