Speaking with Cincinnati native Tom Tsuchiya, you can tell right away that he's living out his dream.

"I always loved baseball, since I was a kid," Tsuchiya told me in a phone call. "My parents were big fans coming from Japan. In Japan, the national sport is not sumo, it's baseball. They came at the right time [for the Reds], in the late '60s, and then me and my brother were born in the early '70s. It's always been a part of my life."

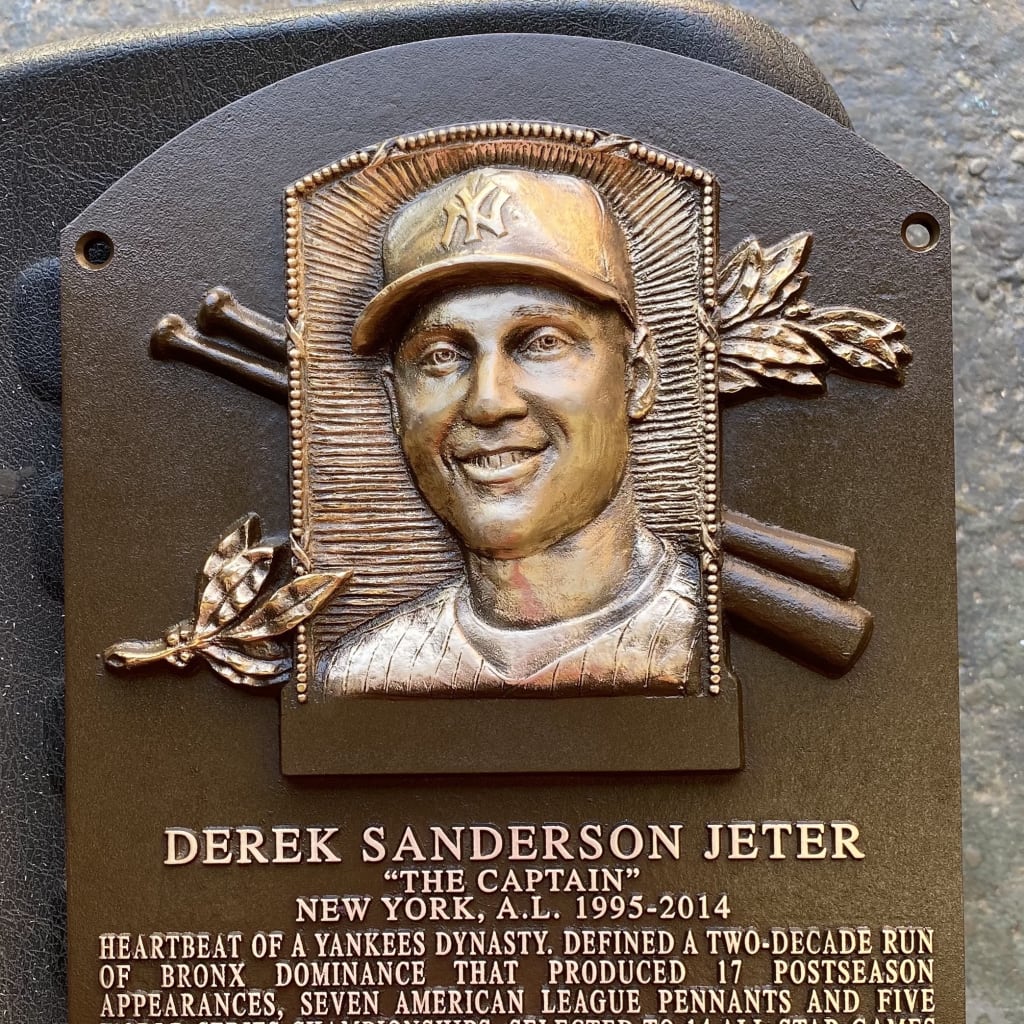

Tsuchiya first got his start in the baseball plaque-making business at his hometown stadium: Great American Ball Park. He created the Pete Rose, Tony Perez and Johnny Bench sculptures, among others. He also helped build the impressive 1869 Red Stockings exhibit.

He's done sculptures for the Padres Hall of Fame and is currently working on an Ichiro bust for the Mariners Hall of Fame.

And since 2016, he's been the National Baseball Hall of Fame's go-to plaque creator. The process doesn't start with him, though. It begins, as expected, in Cooperstown.

"The process starts as soon as an announcement is made about an election to the Hall of Fame," Jon Shestakofsky, vice president of communications and education for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, told me over Zoom. "At that point, we'll begin by selecting the art that will be the basis of the sculpt that will go on top of the plaque."

Generally, the art is an image that illustrates the epitome of who that person was to fans. What they looked like in their prime. Rollie Fingers has the handlebar mustache, Reggie Jackson has his aviator-style glasses.

The art will then be sent to Tsuchiya, who will take a first stab at it. Drafts of the sculpt will go back and forth between the Hall and Tsuchiya until it's just right.

"It's really a team effort," Tsuchiya said.

Tsuchiya will use the one photograph from the Hall but also watch videos of the player or use other angles of the player's face in other photos. The plaque is in 3D, so it helps to have as many different looks of the player, if possible.

Some faces are more difficult than others. It definitely helps if the player's features are bigger and broader: Beards, glasses or other unique facial elements work well with 3D.

"Big Papi's features work very well for sculptures," Tsuchiya told me. "He's a very bold-looking guy, very strong. Yeah, for sculptures, that really helps a lot."

An all-time closer, on the other hand, was a bit harder to draw.

"Mariano Rivera was kind of challenging," Tsuchiya said. "He's a little bit more fine-looking in terms of the features."

The text part of the plaque doesn't go down to Tsuchiya, it gets paired up later with the player's face at the foundry. That component is written up by a small team from the Hall of Fame and, as you can guess, it can be a challenge.

"It can be a daunting task," Shestakofsky said. "You're trying to whittle down a Hall of Famer's career -- we're talking a decade, two decades of incredible moments in the game that put you in the top one percent to ever put on a Major League uniform -- into 80-100 words. It is a daunting task, a difficult task."

The small team has a rough guideline to kind of go by.

"You need to provide enough insight to where someone, 50 or 100 years from now, can walk into that plaque gallery, read the plaque and get that snapshot of the player's career," Shestakofsky told me. "Why was this person important to the game? You're looking to accomplish something quantitatively with the numbers, but also qualitatively with what makes that person different from other folks who've been a part of this game."

Once Tsuchiya's sculpt is approved by the Hall, it goes to Matthews Architectural Products in Pittsburgh -- a foundry that's been working with the Hall for nearly 30 years. This is where it's cast in bronze with the old-school process of sandcasting. The models are also, of course, sent very carefully.

"Oh yeah, we don't just send it in an envelope," Tsuchiya laughed. "They have special crates that are made. You can drop them off the side of a two-story building and they'll be fine."

"Once Tom sends it in, and we get the approval on the text, we make the polymer which is the process used for our patterns," Matthews senior project manager Paul Storino told me in a phone call. "Tom's model already has the bats and the framing with the olive leaves. We take that and we glue it to the pattern with the text."

Then they can begin the casting process. These days, most casting is done with computer programs, but that would cut out Tsuchiya's magical touch.

"When you do it the way we do it, then you can have an artist make the clays and everything," Storino said. "With computers, you're taking a lot of the handwork out of it."

From start to finish, the entire process involving the Hall, Matthews and Tsuchiya, takes about 5-6 months -- generally from around late January to early June. The Hall of Fame hopes to have the finished plaques in-house about 4-6 weeks before the ceremony.

The inductees don't have a say on the text or image and don't see their bronze busts until that moment when the rest of the world sees them on stage. It's the shining moment, after half a year of hard work, proofing and many back-and-forths. Fortunately -- credit to the entire creative crew -- no players or managers have been unhappy with how they've been immortalized forever.

"Resounding positive feedback upon unveiling of the plaque," Shestakofsky said. "A lot of positivity about how accurately someone is depicted with imagery. And I've heard some great comments about the text as well."

Tsuchiya, who's attended the ceremonies every year since he started making the plaques in 2016, loves to watch the inductee reactions to seeing their plaques.

"Trevor Hoffman gave me a big giant hug," Tsuchiya said. "He's not someone who's supposed to get as emotional, but all weekend, he was like a kid in a candy shop. Chipper Jones, I always loved Chipper, he thought it was pretty amazing. Lee Smith was a super nice guy, he loved his plaque.

"It's very amazing. It's satisfying. Very triumphant ... it's a nice way to celebrate. A great sense of accomplishment."