Dodgers manager Dave Roberts issued a vote of confidence in Kenley Jansen on Wednesday night.

“Kenley’s our closer,” Roberts said, after Max Muncy’s 10th-inning home run walked off the Blue Jays at Dodger Stadium, letting Jansen off the hook for his sixth blown save in 32 chances, thanks to a Rowdy Tellez homer.

That the question is even arising would have been shocking not so long ago. Jansen has been the Dodgers’ primary closer since 2012 and their franchise record-holder in saves since ‘16. He’s approaching the 300-save mark for his career and is a three-time All-Star star who has been one of the most dominant relievers of his era. The Dodgers re-signed him to a five-year, $80 million contract in January 2017, a deal that runs through the ‘21 season.

But the fact that Jansen has slipped from his peak is indisputable. And that’s a problem for the Dodgers, not so much as they sail toward a seventh straight National League West title, but certainly as they gear up for an October run that they hope will yield a long-awaited championship.

The solution to that problem could involve Jansen moving away from his reliance on the pitch that made him such a singular force in the first place: his cutter.

Here’s a look at why it’s come to that, and where Jansen could go from here.

Still good, just not the same

It’s not as if Jansen has been ineffective. The 31-year-old’s park-adjusted ERA and FIP are still better than average, and of more than 150 Major League relievers with 40-plus innings through Thursday, Jansen ranked 26th in strikeout rate, 20th in walk rate and 12th in strikeout-to-walk ratio.

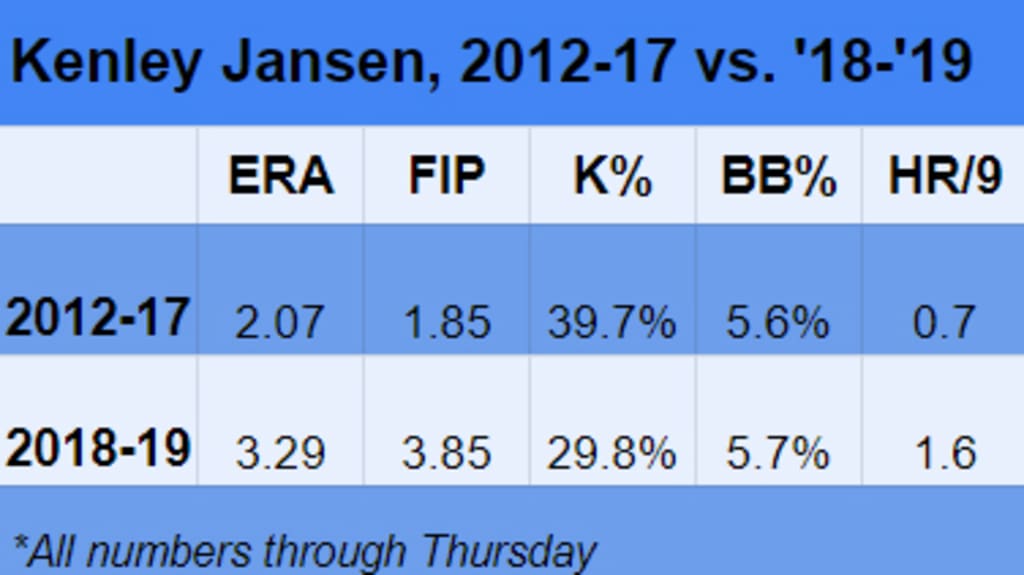

At the same time, a comparison between Jansen’s past two seasons and the previous six shows a stark dropoff.

It’s only been a dramatic fall because Jansen was on top to begin with. But some ill-timed homers -- and homers are an issue for many pitchers these days -- have contributed to three blown saves in the past two World Series, plus six more in 2019. Jansen’s 81% conversion rate in save opportunities is his lowest in seven years.

Cutting it up

Throw cut fastball after cut fastball to hitters who know what’s coming but are helpless to stop it. That was the formula for a closer who was enshrined in the Hall of Fame earlier this summer (Mariano Rivera), and it has been a successful formula for Jansen as well.

Throughout most his career, Jansen has thrown the cutter 85-90% of the time, and he’s had no reason not to. For many years, it rarely got hit.

“In the early part of his career, he just overpowered the league,” Roberts said recently.

But things have changed. Since 2017, the pitch’s average velocity has dropped from 93.2 mph to 91.7 mph. It’s missed bats less often, while yielding more and more hard contact.

In 2017, opponents slugged .306 with five homers in 196 at-bats ending on cutters. Since then, they’ve slugged .429 with 21 big flies in 357 at-bats, including Tellez’s shot into the right-field bleachers to tie Wednesday’s game in the ninth inning.

That ill-fated full-count pitch actually was off the plate inside to the left-handed Tellez, in an area where Jansen’s cutter had produced just one other homer in his career. Still, Roberts offered a critique of Jansen’s approach afterward, even while defending his job.

“I just felt he had a chance to throw a slider down below and went to the well one too many times,” he told reporters. “Actually, it wasn’t a bad pitch. But when you give a guy with power multiple looks in the same quadrant, it decreases your margin. I know Kenley feels bad, but he got a [strikeout] and some soft contact. Unfortunately, he couldn’t put up a zero.”

Time to diversify

Forget the Rivera example. Instead, how about another pitcher who was at the top of his profession, but as increasing age and decreasing velocity crept up, threw fewer and fewer fastballs, and more and more breaking balls, to compensate?

All Jansen has to do is look across his clubhouse at a longtime teammate. As a young pitcher, Clayton Kershaw threw more than 70% heaters. That number dropped over time, and now, in 2019, he throws far more sliders and curves (56%) than 4-seamers (43%). Kershaw may not be quite what he once was, but has a 2.71 ERA this season, including 1.76 since July 1, and has gone at least six innings in all 22 of his outings.

It’s not just Kershaw, of course. Pitchers across baseball are learning to rely more on breaking pitches, and it just so happens that Jansen has a good one.

Opponents are a mere 1-for-24 against Jansen’s slider this season, with no extra-base hits and seven strikeouts, while missing on 41% of their swings against it. In the past three seasons, they are batting .107 and slugging .120. Notably, the slider has not allowed a single homer in that time.

Nobody is suggesting that Jansen should start throwing as many sliders as Kershaw, especially as a reliever. And some of the pitch’s effectiveness may be due to its judicious usage. But it does provide a nice contrast to the cutter, with an average velocity about 10 mph slower. While Jansen throws the cutter up in the zone, the slider has well over 3 feet of drop -- 4.3 inches better than average for pitches of similar velocity -- and more than two-thirds of them go to the bottom third of the zone or below.

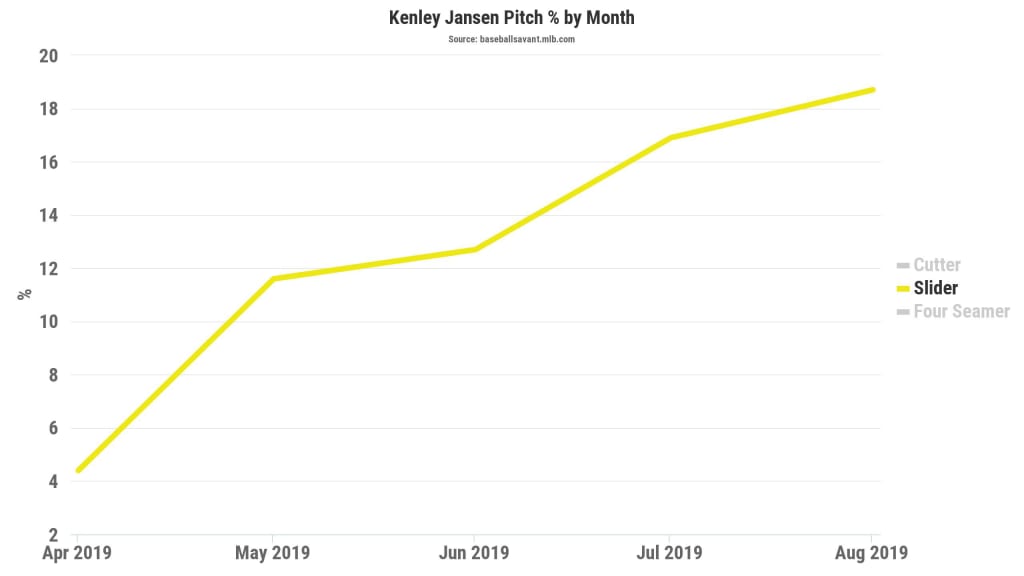

While Jansen not using the slider in that particular instance might have cost him, there is evidence that he is evolving. From 2018 to ‘19, his cutter usage has declined from about 84% to about 77%, with an accompanying rise in his slider usage, which also has climbed with each successive month. (Jansen also throws a fastball that Statcast classifies as a four-seamer about 12% of the time).

It seems likely that trend will continue down the stretch, as Jansen prepares for another postseason of high-pressure, high-leverage moments against dangerous lineups. Jansen is who he is because of the cutter, but if the Dodgers are going to get where they want to go this fall, the slider may have to play a more prominent role.