Second part of a two-part investigation into lefties in baseball, with part one focusing on position players.

A funny thing happened on the way to the Cy Young recently. When MLB.com's Will Leitch and I got together to draft the likeliest pitchers to win the Cy in 2020, it was pointed out that only two of the 20 names we'd selected (Clayton Kershaw and Hyun-Jin Ryu) were left-handed.

That seemed odd, and interesting, though of course the two of us picking a handful of names is hardly scientific. Still, it sent us down a rabbit hole. Were there really fewer great lefty starters in baseball, or is this just a fluke? If there are, then why? Is it just one of those cyclical things, or something more meaningful?

The first thing we did to try to answer that question was to simply look at the 2019 season through the lens of Wins Above Replacement. In WAR terms, a 2-WAR season is considered "average," so we thought an easy thing to do would be to look and see how many lefty pitchers had a 3-WAR season (i.e., above-average) or better last year, and if it was noticeably lower than the rest of history.

Last year, there were nine 3-WAR southpaws in baseball (Matthew Boyd, Patrick Corbin, Marco Gonzales, Cole Hamels, Kershaw, John Means, Mike Minor, Eduardo Rodríguez, and Ryu; there were 28 from righties). Dating back to the start of divisional play in 1969, so spanning 51 seasons, that's the third-fewest in a season -- with one enormous caveat.

Fewest 3-WAR lefties in a season, 1969-2019

7 -- 1994

8 -- 1981

9 -- 2019

9 -- 1992

10 -- five seasons tied

11 -- five seasons tied, including 2018

You see the issue there, right? 1994 was a strike year, where teams averaged 115 games. 1981 was also a strike year, where teams averaged 107 games. WAR is a counting stat, so fewer games played means less time to pile up stats. (Only one hitter in 1981, for example, reached even 25 home runs.) So if we're talking about fewest great lefties in a full season, then we just saw the smallest number in a half-century. Maybe there's something here!

That's not an analysis without its own flaws, obviously, because pitchers simply don't pitch as many innings as they once did, so it's harder to reach any particular WAR threshold. So instead, let's just look at "high-quality lefties over a reasonable number of innings," which we'll do by looking at seasons since 1969, ranked by fewest lefties to throw 100 innings and do so with an ERA+ of 125. (An ERA+ of 100 is league-average for that given season, important since the offensive environment changes so much over the years, so a 125 would be 25% above average. It's also park-adjusted, helpful in the era of Coors Field.)

Fewest 100-inning, 125 ERA+ lefties in a season, 1969-2019

4 -- 2006

5 -- 1999, 1992, 1980

6 -- nine seasons tied, including 2019, 2018, and 2015

OK, so maybe it's not totally unprecedented, but it's definitely on the low end. So far, this is interesting, but not declarative.

But beyond that, there was something notable about last year's playoff rosters, too. The Astros went with an all-righty roster for the ALCS, then did so again for the World Series. That hadn't happened in more than a century, dating all the way back to the first World Series in 1903. This is supporting evidence, not proof; it's still interesting to note that only 2% of Houston's postseason pitches, all in the ALDS, came from lefties.

We've seen this before, though. The 2017 Phillies went all year without a lefty starter. The 2013-16 Brewers somehow went 474 consecutive games without a lefty making a start.

But then again, we're not necessarily just talking about all lefty pitchers. Lefties started 29.1% of games in 2019, which is either higher than their "28% since 1904" number or lower than their "29.7% since 1969 number," depending on what you prefer. Either way, it's not a terribly interesting number in and of itself. There were nearly the same number of lefty starts in 2019 as there were in 2004. No, instead we're looking for very good lefty pitchers.

So let's look forward, for a second. What did the projections expect for 2020? We understand that 2020 won't end up being a full 162-game season, but when we pulled these numbers, the projections didn't know that yet. So, how many above-average lefty pitchers did the computers see for the upcoming season?

Not ... many.

Projected 3+ WAR lefties, 2020

We might just be in a down period. But even if that's the case, well, where are those missing top lefties? Is there reason to believe that it's just about fewer lefties entering the sport? Well ... maybe, actually.

We looked at the Draft over the last 25 years, dating back to 1994. During that quarter-century, just over 19,500 pitchers were drafted. Of that group, just over a quarter (27.5%) were left-handed. If we rank those 25 draft years by lowest percentage of lefty pitchers, look what happened:

Lowest percentage of lefty pitchers drafted, 1994-2019

23.9% of all pitchers -- 2018

24.3% -- 2019

24.8% -- 2016

25.8% -- 1995

25.6% -- 2007

The smallest number of lefty pitchers drafted, both in raw total (157) and percentage of all pitchers (23.9%) happened in 2018. The second-lowest was 2019. Toss in 2016, and the three smallest lefty pitcher Draft classes of the last quarter-century have come in the last four years. That doesn't seem like a coincidence.

Ideally, we'd be able to go to the amateur levels and scour high school and college data to see how many lefty pitchers we have there, but that kind of data doesn't easily exist, so we're left with a few cherry-picked anecdotes. LSU, for example, went the entire 2019 season without a lefty, mainly due to injury.

In the shortened 2020 season, only 11% of LSU's innings came from lefties. That's 17 1/3 innings from freshman Jacob Hasty and 12 2/3 from community college transfer junior Brandon Kaminer -- though, as Kaminer's LSU profile states, he's a "a strike thrower with an advanced feel for his change-up and slider [and] has a mid-to-upper 80s fastball that is capable of getting into the low 90s," which is exactly the kind of profile that may not be appealing to the Majors right now.

OK, so it seems like there's something here. What could be causing this? We spoke to some experts around the sport, and we have some theories.

Theory 1: It's because velocity is all the rage.

"With the newer thought that 'higher velocity equals better,' that puts lefties at a disadvantage," said an analyst for a National League team, "because they tend to have lower average velocities. This may push lefties into relief in attempts to increase their velocity, and push some of them into [lefty specialist] roles."

Right. Baseball is all about velocity, now more than ever before. That's in part because it's easier than ever to track at lower and amateur levels, and -- not that we haven't known it's good to throw hard for decades, obviously -- because the data has made it very clear that it matters.

In 2010, now-Braves analyst Mike Fast's seminal "Lose a Tick, Gain a Tick" piece estimated "that a starter’s run average would increase by about 0.25 for every mph lost off his fastball, and 0.45 per mph for a reliever." In 2014, FanGraphs revisited the study and found the effects held true. In 2019, MLB.com's Tom Tango concluded in a study that "I think we can safely say that it's about 0.20 runs per 9 IP per MPH." And earlier this month, Chris Langin, an intern at data-driven pitching factory Driveline Baseball, shared yet another study that showed the same.

Put another way, in 2019, look at the difference in outcomes on fastballs (four-seams, two-seams, and sinkers) split by velocity. It's enormous. Velocity is valuable.

95 and above: .249 average, .419 slugging

94 and below: .291 average, .514 slugging

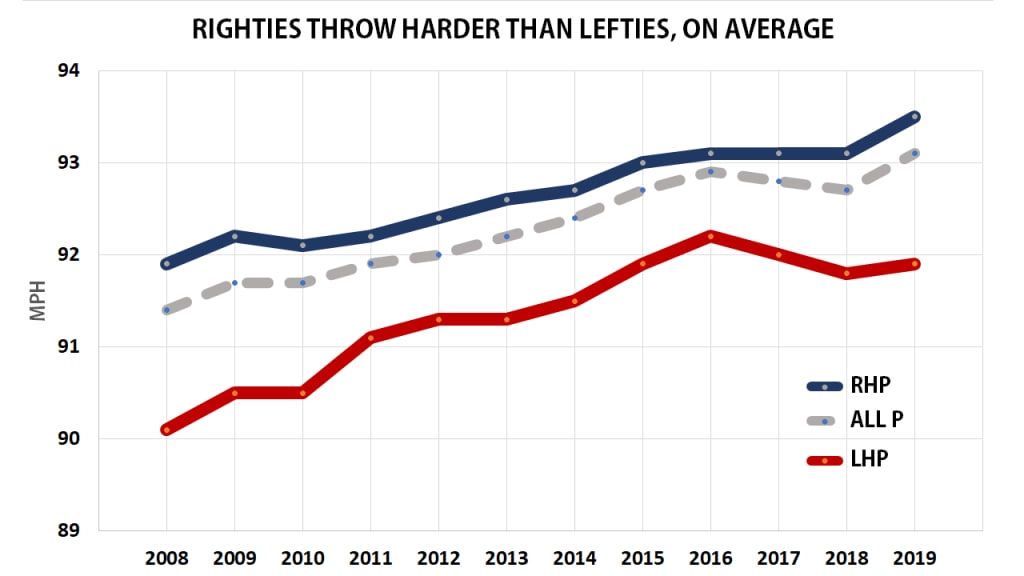

As you already know, velocity has been increasing across the bigs for years, but it hasn't been equally distributed. Last year, only 11.4% of pitches that were 98 mph or higher came from lefties, and 33% of those came from a single pitcher, Aroldis Chapman.

That said, lefties have consistently been one to two miles per hour lower -- and, oddly, there's been a small decline since a 2016 peak, while righties keep going up.

"Some of it is the velo thing," said FanGraphs lead prospect analyst Eric Longenhagen, speaking about pitchers entering the pros from high school and college baseball. "Guys are just being selected out. All of these pitchability lefties, their chances of starting are probably greater than these power arm dudes with zero control ... but [the power guy’s] chance of being anything is probably better than the soft-tossing lefty at 88-91."

"So touch-and-feel types get drummed out," said ESPN prospect writer Kiley McDaniel, "and [lefties are] disproportionately that."

“It is rare to find lefties who throw hard and have starter command," Longenhagen added, "and so many of them are washing out.”

"I think the smaller strike zone increasing the need for velocity probably changes the outlook of drafting a certain number of lefties versus righties," said an analytically-inclined pitching coordinator of one Major League team.

“Velocity is the number one thing,” Kyle Boddy said to the Washington Post last year. Boddy founded Driveline Baseball and was hired last fall as the Reds' director of pitching initiatives/pitching coordinator. "You hear all this stuff about, ‘You don’t have to throw hard; you just have to learn to pitch.’ It’s not true."

Or, as Jamie Moyer, the all-time king of "crafty lefties," explained to the Orange County Register in 2019: “Look at the younger generations -- high school, college, Minor Leagues, everybody’s trying to light up a radar gun, throw 100 mph."

If righties are better at doing that, which it seems they are, then this would certainly explain a lot, including why fewer lefties have been drafted.

Theory validity points: 10/10

Theory 2: It's because technology has eliminated a pro-lefty bias.

You know what else is all the rage, aside from velocity? Spin, or more accurately, the movement that a high-spin pitch with excellent spin efficiency can provide. That's generally played out in an up-and-down fashion, with the extremely oversimplified explanation being that it's easier to miss a horizontal bat above or below it than it is to go to the left or right of it. (See: Tampa Bay monster reliever Nick Anderson.)

"There's been a visual bias [in scouting]," suggested Longenhagen. "The vertical break fastball was not something from, where scouts sit [behind the plate], they can discern. The fastball with tail was easier to identify visually. It took the tech for us to learn that. [For example], the Colin Poche spin axis ... we couldn't figure why this guy is missing all these bats. The tech gave us something more concrete. This guy’s got crazy spin angle and his approach angle gives him elite vertical rise."

"Vertical movement is hard to see visually. Horizontal movement is easier to see. We were biased towards that visually for a long time. If it’s true that lefties can’t throw it quote unquote straight ... and straight means one of those vertical breakers that we’re missing ... that would bias us towards lefties in the past that may not be now.”

Tampa Bay's Poche doesn't throw hard -- just 92.2 mph on his four-seamer -- and he doesn't have much of a repertoire, throwing that fastball nearly 90% of the time. But he gained notice as he began to pile up ridiculous strikeout numbers in the Minors, and he posted an elite 34.8% strikeout rate in the Majors last year, thanks to the top vertical rise mark in all the land. As Longenhagen noted, what he does is harder to see visually than a tailing or sinking two-seamer.

"I’m sure there’s some teams looking mostly at spin," said the pitching coordinator. "So I guess the priorities have possibly changed for some organizations?"

Still, it's difficult to fully tease this out with data, because we definitely don't have enough reliable movement data at the lower and/or amateur levels, and the data we do have at the Major League level would be collected only among those good enough to have survived that far in baseball in the first place -- and, in many cases, among pitchers who were drafted 10 or 15 years ago. So while we can't say that this is absolutely true, it certainly sounds plausible.

Theory validity points: 6/10

Theory 3: Maybe lefties throw pitch types that are off-trend.

Sinkers are dead. Fastballs are dead, really, because 41% of pitches were non-fastballs in 2019, continuing a steady creep up from just over 33% in 2008. That's especially true for two-seamers/sinkers, which comprised 25% of all pitches in 2010 but fell to a mere 16% in '19. The reason why is well-known: with everyone going so homer-happy, it's better to miss bats entirely than attempt to induce a grounder or a weak ground ball. When you think of the "crafty lefty" you think of getting by while interrupting timing, more than blowing hitters away.

It hasn't played out in strikeouts, either. Lefty pitchers struck out 17% of hitters in 2002, and nearly 23% in 2019. But righty pitchers have gone from ... 17% in 2002 to just over 23% in 2019. It's a similar story with inducing grounders.

This probably isn't it.

Theory validity points: 0/10

Theory 4: It's a reaction to the fact that there are fewer lefty batters now.

This would make sense, because if there are fewer lefty batters, then lefty pitchers lose some of their advantage, and ...

Wait. There are fewer lefty batters now? Why?

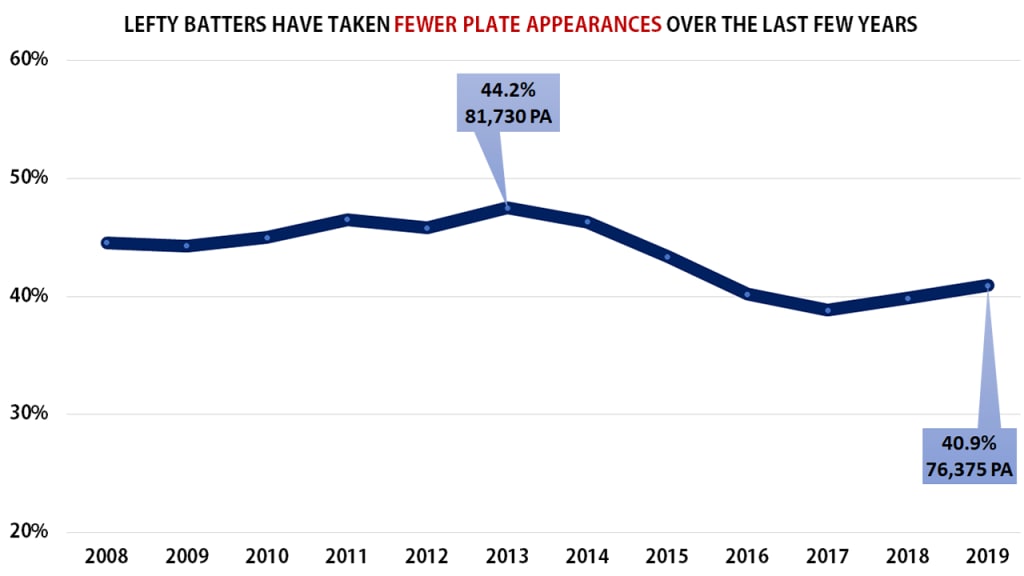

This surprised us too. So much, in fact that we wrote an entire separate article detailing what happened here. But, as you can see, we're down a few thousand lefty plate appearances from where we were just a few years ago. That's not unprecedented, as it had been just as low in 2006, but before that, the rate of lefty plate appearances hadn't been that low since 1983.

As we detailed in the accompanying piece, there are a few different theories as to why that is, but a big part of it seems to be about positional versatility, in that shorter benches require players who are capable of playing several positions, and so this is less about lefty hitters and more about lefty throwers. That is: 2019 had the fewest number of semi-regular (250 plate appearances) lefty throwers since 1964 ... and the highest number of lefty-swinging right-handers ever.

In some sense though, this is counter-intuitive: if there are fewer good lefty pitchers, then you'd probably want more lefty hitters. And that hasn't really played out much.

Theory validity points: 2/10

Theory 5: It's because no one's stealing bases, and a good lefty pickoff move is less valuable.

How about this one? With the sport overrun by strikeouts and home runs, stolen bases -- and attempts -- have collapsed.

Thus, one advantage lefties have always had, the ability to keep an eye on that runner on first base while the righty pitcher has had to look over his shoulder, is gone. Plus, there's increasing anecdotal evidence that more and more pitchers are ditching the windup and using the stretch full-time, which could make them quicker to the plate anyway.

This is unlikely to be a major point that defines whether or not a lefty pitcher gets drafted or succeeds. But it's a minor thing that might take away one advantage lefties had -- or, to put it another way, allows righties to catch up a little.

Theory validity points: 1/10

Theory 6: Maybe righty pitchers are more attractive.

"[For years, the thinking was that] you’d rather have the lefty because they’re just rarer," said Longenhagen, "but I’ve gotten pushback from intellectually progressive front offices that this kind of heuristic, conventional thinking is true.”

In other words, maybe the best kind of pitcher is simply the best kind of pitcher. That's essentially what Joey Votto said to Vocativ in 2016: "It also could be that, in the past, [teams] felt obligated to have a left-hander. Maybe now they’re realizing, just have effective pitchers.”

If that's true, we might be able to see it in the data. We might be able to see that if righties are better at neutralizing lefties, then the requirement of having a lefty might not be as important. That is, if there's a reason righties are more attractive, then the push-and-pull of that is that lefties might be less attractive.

As one National League assistant GM said, "I wonder if this is also a decision [that is] going to be made less on the basis of lefties themselves and more about a subtle change that is advantaging right-handed pitchers."

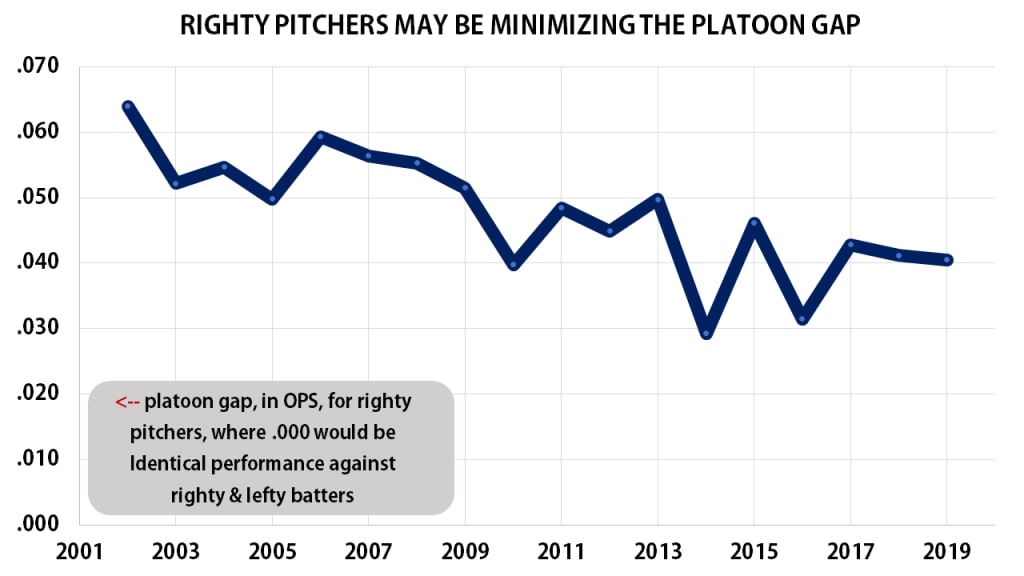

As it turns out, righty pitchers have cut the platoon gap a little over the years, by about 25 points of OPS on an inconsistent downward slope. It's not a big deal, but it's something.

"We’ll do it a little differently," then-Astros manager AJ Hinch said last summer, when his team had no lefty relievers, "but [the bullpen] being able to combat the left-handedness of another lineup is a great advantage for us."

Remember above when we said LSU didn't have a lefty last year? Their coach, Paul Mainieri, told The Advocate last year why that didn't bother him so much: "Even though some guys are right-handed, they actually do really well against left-handed hitters because of what their repertoire of pitches is."

In 2017, Rays manager Kevin Cash spoke to MLB.com about righty reliever Danny Farquhar's success against lefty hitters.

"He's had some success against lefties," Cash said. "The fastball-changeup combination. He throws well against righties also. When you don't have a bunch of left-handed pitchers, you try to find the guy that's had some success and he's probably the most after [lefty Xavier Cedeño]."

The Rays currently employ righty Oliver Drake, who is one of baseball's most dominating pitchers against lefties from either side, allowing a mere .147/.163/.196 line against them in 2019, thanks in part to throwing 60% split finger fastballs, the highest number in the American League.

Theory validity points: 3/10

Theory 7: Maybe it's just a fluke.

Maybe we're overreacting to a handful of numbers. Maybe there's no there there. After all, Blake Snell is generally considered to be a pretty great lefty, but his 2019 was an injury-plagued mess. That's not likely predictive of his future. Then again, that sort of thing happens all the time, to pitchers both lefty and righty. If there had been a full 2020 season, ace lefty Chris Sale was already not going to be a part of it, thanks to his spring Tommy John surgery.

"I still think there’s a lot of randomness involved," said the pitching coordinator, who added that he "still values lefties a lot," and expressed hope his team would select one highly in the upcoming Draft.

"It’s possible," Longenhagen said, "that the sample of lefty pitchers in baseball is small enough that an uncommon number of them have been hurt or failed to develop."

Maybe so. In a decade of Drafts dating back to 2010, only four lefty first-round picks (Sale, Snell, Drew Pomeranz and Kyle Freeland) have managed to post even 10 WAR over a career.

Back in 2008, Newsweek ran a headline that read "SCIENCE: WHY LEFTIES MAKE BETTER BASEBALL PLAYERS." That may or may not actually have even been true at the time. But the world has changed a lot in the last 11 years, and we're seeing that reflected a lot in the types of players and pitchers who get selected, and the types who eventually succeed. We may yet see this turn around; as the pitching coordinator suggested, Sale and Randy Johnson are now and always going to be the near-ideals of pitching dominance.

Still, it's a down period. We're looking to you, Asa Lacy or Reid Detmers, the top two lefty-pitching prospects in the upcoming Draft. No pressure, though.