Babe Ruth and running don’t seem to go together very well. While The Babe is regarded as one of the greatest athletes of all time, his commitment to physical fitness clearly paled in comparison to his love for food and beer. And with his power at the plate, it’s not like he needed to leg out many bunt singles.

To my knowledge, he didn’t run any races, and he probably didn’t log many miles either. But the number of times he trotted around the basepaths in Major League games -- 714 to be exact -- in an era when entire teams were hitting fewer baseballs out of the park than he did, is the main reason we have celebrated his accomplishments for an entire century.

This year marked the 100th anniversary of The Babe’s first season with the New York Yankees. Ruth, who came into the league as a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, played his first game as a Yankee on April 14, 1920, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. The Yankees lost that game to the Athletics, and Ruth, playing center field that afternoon, collected his first two hits with New York. The Babe finished that season with 54 home runs and 135 RBIs, both of which led all of baseball. Ruth would go on to set the Major League career home run record, which stood for decades.

Ruth was a fascinating figure long before he arrived in New York, and he remained so until his death in 1948. As this important anniversary approached, I combined my passion for running with my constant desire to learn more about the man who revolutionized sports; who is, in my opinion, the greatest athlete in history. What follows is a unique roadmap that weaves through the most significant landmarks in Ruth’s life. I explored most of these places on foot, running races in the cities, small towns and ballparks that ultimately made The Babe.

If you’re a fellow runner and a baseball fan with a special appreciation for Ruth’s legacy, I hope you’ll register for one or more of the races described here. But even if you’re only as dedicated to running as The Babe was, you can still check out any of these destinations at the same pace that the Bambino himself might have. The courses may change over time, but the presence of Ruth’s legacy in these locales remains everlasting.

Baltimore Running Festival

Every October for the last 20 years, runners have taken part in races through the city where George Herman Ruth was born and raised. The Baltimore Marathon, Half Marathon and 5K begin in the Inner Harbor area, a short distance from the brick row house at 216 Emory Street where Ruth was born on Feb. 6, 1895.

The last half-mile of the races take runners along Eutaw Street, past a nine-foot tall and 800-pound bronze statue of The Babe and in between Oriole Park at Camden Yards and the brick warehouse that now serves as a backdrop to the stadium. The statue was designed to depict Ruth in 1914, when he began his professional baseball career with the Baltimore Orioles, then a Minor League team.

During Ruth’s childhood, his father owned and operated a cafe located just beyond where the left-center-field wall at Oriole Park currently stands, and George Sr. and his family lived in adjoining rooms there. The most compelling connection to the Baltimore Running Festival is that as a mischievous child, Ruth would often hang out at the Lexington Market, located a few blocks from the current ballpark. According to a Baltimore Sun article from 1995, on several occasions, Ruth knocked over baskets of fruit and vegetables and then ran away from angry vendors toward home. The route from the market to Ruth’s house follows, at least for a few hundred yards, the same streets as the last part of the courses for the Baltimore Marathon and Half Marathon.

I completed the Baltimore Half Marathon on a crisp fall day in 2016. A few minutes after crossing the finish line and collecting my medal -- in the shape of a Maryland Blue Crab with Baltimore’s skyline engraved on the inside of it -- I took a short walk around Camden Yards to Emory Street, where today, the house that Ruth was born in serves as a shrine celebrating his life. The Babe Ruth Birthplace & Museum is open to the public, and it includes exhibits featuring rare memorabilia from Ruth’s baseball career as well as from his childhood and his life away from the game. If you make the 26.2-mile run or the 13.1-mile trek and your sense of direction is off, you can follow a pathway of baseballs painted on the sidewalk beginning at the Ruth statue (located at the entrance to Oriole Park at Camden Yards on Eutaw Street) and ending at the National Historic Site.

The Providence Marathon, Half Marathon and 5K, and the Narragansett Beer Races

The Babe’s Minor League career was short and sweet. He played for the Baltimore Orioles -- a top-tier Minor League team -- during the first part of the 1914 season. Then, on July 9, his contract was sold to the Boston Red Sox for about $25,000, along with the contracts of fellow Orioles players Ernie Shore and Ben Egan. The Red Sox threw the 19-year-old Ruth to the wolves, adding him to their big league roster as soon as he reported.

Ruth pitched well enough to win his debut against the Cleveland Indians on July 11, but over the next month, he would only take the mound one more time. On Aug. 18, he was sent down to the Minors -- to Providence, R.I., to be exact. It was in that small city, 40 miles from Boston, that The Babe’s incredible ability began to take shape.

While he hit just one home run during his lone season at Providence, Ruth pitched in some big games for the Grays, helping the team win the International League championship. Between the 1914 championship and the notoriety that Ruth brought to both the team and the industrial city, it was a banner year for the Grays, who played their home games at Melrose Park in South Providence.

There are several races in Providence each year, but the Providence Marathon is the premier running event in the city. Each spring, thousands of runners take on the 26.2-mile course, as well as the half marathon and 5K challenges that all begin and end in downtown Providence -- the neighborhood that Ruth and most of his teammates lived in during the 1914 season.

Runners in all three races begin by heading south toward the site where Melrose Park once stood and which is now a parking lot. Of the three courses, the 26.2-mile route travels the farthest south along the Providence River, and although it doesn’t run directly in front of the site of Melrose Park, runners can get a good look at the South Providence neighborhood that was home to the Grays in the early 1900s from a path directly across the water.

Although I have not run any of The Providence Marathon races yet, I plan to knock one of them off my “Babe Ruth bucket list” in the near future. But knowing that I would be publishing this story before that could happen, I chose to run another Providence-area race.

I picked a running event that I believe the Bambino would have approved of, the Narragansett Summer Running Festival. The midsummer 5K, 10K and half marathon take place in nearby Easton, Mass., a small New England town located halfway between Providence and Boston -- the two cities that the Babe pitched for after getting traded to the Red Sox. Part of Ruth lore, of course, is that he had a penchant for drinking beer and having fun, and this running festival is not only sponsored by a beer company, but its tagline reads, “The Narragansett Beer Races, the Most Fun Racing Series in New England.”

Ruth also loved the New England countryside, so much so that he purchased a farm in rural Massachusetts during his time with the Red Sox. As I weaved through several picturesque communities on a 90-degree July morning in 2019, I got a better understanding of why The Babe enjoyed spending time there. Every one of the 13 miles that I ran featured breathtaking scenery, and after the last tenth of a mile, I crossed the finish line and collected a medal in the shape of a giant beer bottle cap. I then took a few sips of an ice-cold Narragansett and made a toast to the Sultan of Swat.

Run to Home Base

Before the most significant deal in sports history, when Ruth’s contract was sold to the Yankees prior to the 1920 season, he was a top-line pitcher for the Red Sox. Ruth’s first Major League game was at Fenway Park, and during his six seasons on the mound with Boston, he posted an 89-46 record with a 2.19 ERA. He won 23 games and earned an American League-best 1.75 ERA in 1916. The following season, Ruth won 24 games and led the Majors with a now-incomprehensible 35 complete games.

The Babe also showed glimpses of the unprecedented power he would ultimately bring to New York, leading the Majors with 11 home runs in 1918 and with 29 in ‘19. Ruth’s contributions played a big role in bringing three World Series championships to Fenway Park, including the last one the team would win for almost a century.

Each summer, the Boston Red Sox Foundation organizes 9K and 5K races to raise funds for the Home Base program, dedicated to providing veterans, service members and their families with clinical care, wellness, education and research.

Both races begin directly in front of Fenway Park on Jersey Street. Runners cross the Charles River on the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge, wind their way through Cambridge and then make their way back to Boston. The final part of both races is tremendously gratifying for any sports fan. I will always remember running into Fenway Park and making my way onto the outfield warning track, raising my hands as I dashed beside the Green Monster and finally made my way to the finish line at home plate.

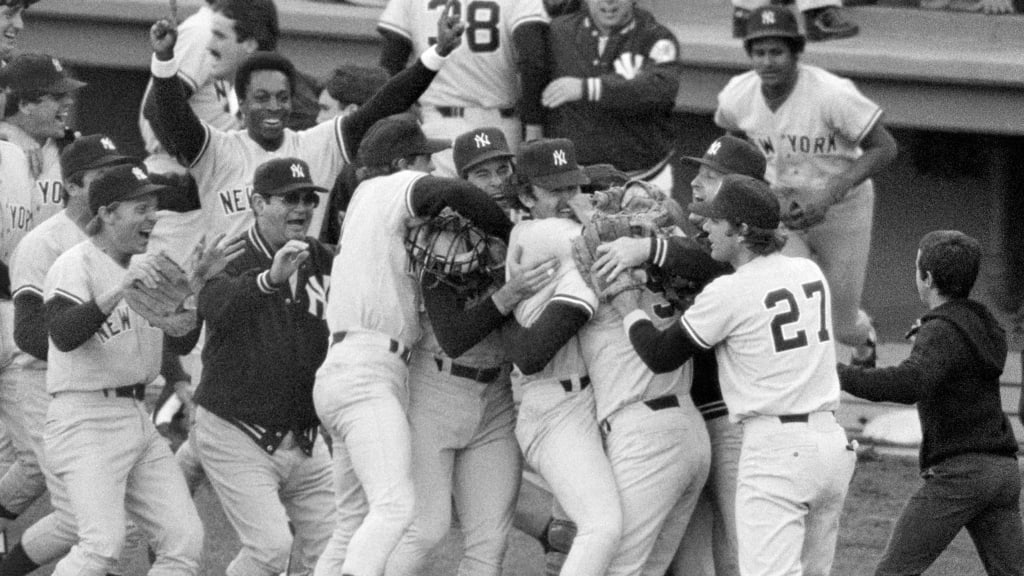

The sale of Ruth from the Red Sox to the Yankees sparked the greatest rivalry in sports, and in the century that has passed, there have been several central figures in the battle of the two franchises. In 1978, Yankees shortstop Bucky Dent became an unlikely hero when he hit a home run over the 37-foot left-field wall at Fenway Park, the same Green Monster that I ran alongside. Dent’s home run secured a Yankees victory that afternoon in a one-game playoff that came on the heels of a monumental late-season comeback. The Yankees went on to win the Fall Classic, and Dent took home World Series MVP honors.

Dent accompanied me to Boston on the weekend I ran the Fenway Park race in 2017, and nearly 40 years after his teammates greeted him at home plate, well, he greeted me in the same spot. Not a bad moment to keep in your memory bank forever.

Bronx 10 Mile

The South Bronx, and specifically the corner of 161st Street and River Avenue, is where the most important chapters of Ruth’s legacy were written.

Three seasons after Ruth joined the Yankees, the team moved into Yankee Stadium, having worn out its welcome at the Polo Grounds, where The Babe had become more of an attraction than his team’s landlord, the New York Giants.

Ruth’s immense, game-changing popularity was the reason the Yankees needed a new state-of-the-art facility, and in 1923, the Bambino christened Yankee Stadium with an Opening Day home run, the first long ball hit there. He finished that season with a Major League-leading 41 home runs and 130 RBIs, powering the Yankees to their first World Series championship.

In the Bambino’s 15 seasons with the Yankees, he led the league in home runs 10 times, crushing more than 50 long balls in four seasons. Ruth’s 60 home runs in 1927 set a record that, although since broken, remains revered.

It was at Yankee Stadium that Ruth not only helped the Yankees win their first four championships, but it also was where he established himself as one of the biggest celebrities in the world. By the time Ruth played his last game for the Yankees in 1934, he had clubbed more than 700 of his 714 home runs.

Each September, thousands of runners begin the Bronx 10 Mile a few blocks northeast of Heritage Field, where The House That Ruth Built stood for more than 85 years. After heading north along the Grand Concourse for about five miles, the runners turn around near the New York Botanical Garden and follow the same route back toward Heritage Field and the Yankees’ current home.

From my experiences, the best part of most races is the finish line, and that is especially the case with the Bronx 10 Mile. Just before reaching the 10-mile mark, the course turns right, bringing runners from the Grand Concourse to 161st Street. As the runners cross River Avenue and head toward Babe Ruth Plaza, they are flanked by Yankee Stadium on the right and the site of the actual field that the Bambino played on to the left before reaching the finish line.

Although this wasn’t a destination race for me, it was certainly on my bucket list. I’ve now run it twice, and each time, I thoroughly took in the atmosphere at Heritage Field, where after crossing the finish line on a historic spot, runners can be found relaxing and posing for photos that offer a special backdrop: Yankee Stadium.

Race to Wrigley 5K

Ruth earned legendary status because he hit so many home runs. He became part of American folklore because of how dramatically he hit those home runs, and because of how far several of them traveled.

Of all the home runs Ruth slugged, none was as famous or dramatic as the one he smashed in Game 3 of the 1932 World Series at Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

The Yankees held a 2-0 lead in the Fall Classic, and before Game 3 began, things got heated at Wrigley. As Ruth launched one baseball after another into the seats during batting practice, fans began to taunt him, some reportedly even throwing lemons at him.

“I’d play for half my salary if I could hit in this dump all my life,” Ruth told Cubs players before the game, suggesting that Wrigley Field was not a challenging park to hit home runs out of.

Ruth backed up his claim in the first inning, swatting a three-run homer.

In the fifth inning, with the score knotted at 4, Ruth came to the plate with the crowd and the Cubs’ players riding him. As the story goes, The Babe shouted back toward the home dugout, then pointed in the direction of center field. Ruth launched the next pitch into the center-field seats, and the Yankees went on to sweep the World Series.

Historians will forever dispute whether Ruth actually called his shot when he pointed, but regardless of his true intent, the event remains one of the most famous tales in the history of American sports.

The Race to Wrigley takes place in early May. For me, trekking through the streets of Chicago’s Wrigleyville neighborhood and then sprinting into Wrigley Field from the center-field entrance, not far from where Ruth’s “called shot” landed, was one of the coolest running experiences I’ve ever had.

After entering the ballpark, which is more than 100 years old, the race led me and my competitors along the concourse from center field toward left field and around to home plate. The best part of the race was running back out of the ballpark underneath the famous Wrigley Field marquee, which that morning read “Race to Wrigley 2018.”

The medal I received after crossing the finish line a block away was a silver replica of Wrigley Field’s signature red sign, the perfect keepsake from a memorable race.

New York City Marathon

While Ruth was carving his name into sports lore in the Bronx, he lived at various locations on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Following his playing career, The Babe spent his last days in uniform at Ebbets Field as a coach for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The New York City Marathon weaves through all five of the city’s boroughs, including Brooklyn and the Bronx, before concluding in Manhattan’s Central Park. With more than 50,000 runners competing in the New York City Marathon, the race -- traditionally held in early November -- is the largest of its kind, as well as one of the most recognized running events in the world.

Completing the New York City Marathon in 2017 in a personal-record time of 4:01:50 will always be one of my greatest thrills, but the whole experience of running the 26.2 miles that led me to its iconic finish line in Central Park was just as exhilarating. Traveling from Staten Island to Central Park on foot and passing through neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Manhattan gave me greater perspective on just how special the Big Apple is.

Ruth loved hamming it up for the crowd, and when amateur athletes like myself cross the Queensboro Bridge into Manhattan at Mile 16, we get a small taste of what it must have been like to be Babe Ruth. The roar of cheering spectators along First Avenue can be heard long before runners cross the East River and, trust me, it’s electrifying.

There are hundreds of other races in New York every year that are less challenging than the marathon. Two prominent long-distance courses that bring runners close to landmarks from Ruth’s life are the NYC Half and the Brooklyn Half, both of which start near the former site of Ebbets Field.

Boston Marathon

The Boston Marathon is the Babe Ruth of running races. It’s the oldest marathon in the world, having first been run in 1897. Featuring the most competitive field, Boston is also the most prestigious marathon. It’s the most difficult race to gain entry into, and its course is one of the single most challenging routes of any marathon on the planet.

From its inception until 1968, the Boston Marathon was held each year on Patriots' Day, a holiday first observed in Massachusetts in 1894 to commemorate the battles that started the American Revolutionary War. In 1969, the holiday and the race were moved to the third Monday in April. The Red Sox began playing a home game on the morning of the race in 1903, and that tradition is still in place today.

The most exciting run of my life brought me past Fenway Park, when I ran the Boston Marathon in 2019. Although I was dealing with the rigors of the course at Mile 25, I was energized by the sight of Fenway Park and the iconic Citgo sign that looms behind the ballpark. The familiar sounds of a baseball game -- which could be heard from Lansdowne Street behind the Green Monster -- were comforting. In retrospect, I’m even more amazed with the history of this great race, especially when realizing that more than 100 years before I competed in it, runners dashed along the same course and past the same ballpark. When my running predecessors made it to Fenway Park in 1918, little did they know that Ruth was on the hill for the Red Sox, pitching a complete game against the New York Yankees.

Ruth’s playing career also ended in Boston. Following his tenure with the Yankees, Ruth signed his final contract as a player with the Boston Braves at Braves Field prior to the 1935 season. He played in just 28 games for the Braves that year before hanging up his spikes.

Boston University purchased Braves Field in 1953, and today, long since being renamed Nickerson Field, it remains an athletic complex for the school’s athletic program -- and it’s located next to the Boston Marathon route at Mile 24.

Philadelphia Marathon and Half Marathon

Not only did Ruth play his first game as a Yankee in Philadelphia, but more than 15 years later, he played the last Major League game of his life in the same city. In between those two landmark dates, Ruth made himself at home in the City of Brotherly Love, batting .357 in 171 games at Shibe Park with 68 home runs -- more than he hit in any other road ballpark.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Ruth’s 548-foot blast on May 22, 1930, at Shibe Park was the longest of his Major League career. Two days before coming close to hitting a baseball out of Yankee Stadium, Ruth connected with a Howard Ehmke pitch in the first game of a Thursday doubleheader in Philly, and the baseball cleared the park’s right-field wall, 20th Street (located directly behind the venue), a two-story row house, the connecting backyards and the houses on parallel Opal Street.

While that moment was a high point in Ruth’s career, what took place in 1935 about a half-mile from Shibe Park was not. But it was even more historic. Playing in his lone season with the Boston Braves, Ruth appeared in his final Major League game on May 30 against the Philadelphia Phillies at Baker Bowl.

Although The Babe had reclaimed some of his old glory a few days before, when he blasted three home runs in Pittsburgh on May 25, he was all but done when the team got to Philly. In his last game, played in front of 18,000 fans, Ruth grounded out to first base in the first inning. In the bottom of the frame, he misplayed a fly ball in left field. When the third out was made, Ruth walked across the outfield to the clubhouse -- located behind center field -- rather than jog to the visiting dugout. Just like that, his playing career was over.

Shibe Park and Baker Bowl were both located in North Philadelphia, on either side of West Lehigh Avenue, about a half-mile from each other. Kelly Drive, which runs through Fairmont Park along the Schuylkill River, is located about a mile and a half west of where the two ballparks once stood. After making their way through the city streets for about 13 miles, Philadelphia Marathon runners get to Kelly Drive and follow a path along the river until Mile 20 before turning back and racing to the finish line in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The 2016 Philadelphia Marathon was my first 26.2-mile race, and that came a year after I ran my first half marathon in the same city. Although I didn’t know it at the time, 2015 was also an anniversary year for Ruth. He played in his first World Series game 100 years prior, against the Phillies at Baker Bowl. Ruth pinch-hit in a Red Sox loss, but his team captured the title in five games.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Base Race

Less than a year after Ruth played his final game, sportswriters from around the country cast their votes in the first Hall of Fame election. Ruth, along with Ty Cobb, Cy Young, Walter Johnson and Connie Mack, earned a spot in the inaugural class of 1936. The National Baseball Museum, as it was known then, had not yet moved to its permanent home, so the five greats would have to wait more than three years for their induction ceremony.

On June 12, 1939, the museum officially opened, and on that same day, members of the first four classes were inducted. The ceremony took place in front of the museum on Main Street in Cooperstown, N.Y. Ruth and the other inductees spoke to the crowd, then took part in a parade down Main Street that concluded a few hundred yards away at Doubleday Field, where they played in an All-Star Game.

Playing against some of the best players from that season, the 44-year-old Ruth came to the plate in the fifth inning and hit a pop fly that was caught in foul territory. Although he didn’t dazzle the crowd with a blast, history was still made at that tiny ballpark that afternoon, as the sport’s greatest player appeared in a game at the field that had been deemed the “Birthplace of Baseball” by a commission more than 30 years prior.

As part of the Baseball Hall of Fame Classic Weekend, normally held each spring on Memorial Day weekend, there’s a competitive 10K race and 5K fun run. I’ve competed in the 10K twice over the last few years, and I can’t wait to run it again. The race starts in the parking lot of Doubleday Field, and runners are invited to warm up on the warning track of the ballpark.

After making a loop around scenic Cooperstown, runners head back toward Main Street before turning right at the village’s only traffic light. The last dash follows a historic stretch of land along Main Street. It also allows runners to trace the steps that Ruth took from the old Cooperstown train station to the Hall of Fame upon his arrival in the quaint town all those years ago, when his journey from the hardscrabble neighborhood of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor to a celebrity on par with any star sports has ever produced culminated in a permanent spot among baseball’s immortals.

This article appears in the 2020 New York Yankees Official Yearbook. To order your copy, please visit www.yankees.com/publications.