Like all great things in life -- from garage bands to software companies -- it started in a basement. The National Ballpark Museum -- located just 315 feet from Coors Field -- is a space devoted to the Roman Coliseums of modern life, filled to the brim with the greatest jewels from the game's classic ballparks. And it all started in the private residence of CPA and baseball superfan Bruce Hellerstein.

"If there's a regret, it's not being able to see these old ballparks in person," Hellerstein, the 72-year-old founder and curator, said in a recent phone call, "but I did the next best thing to try to create their feeling."

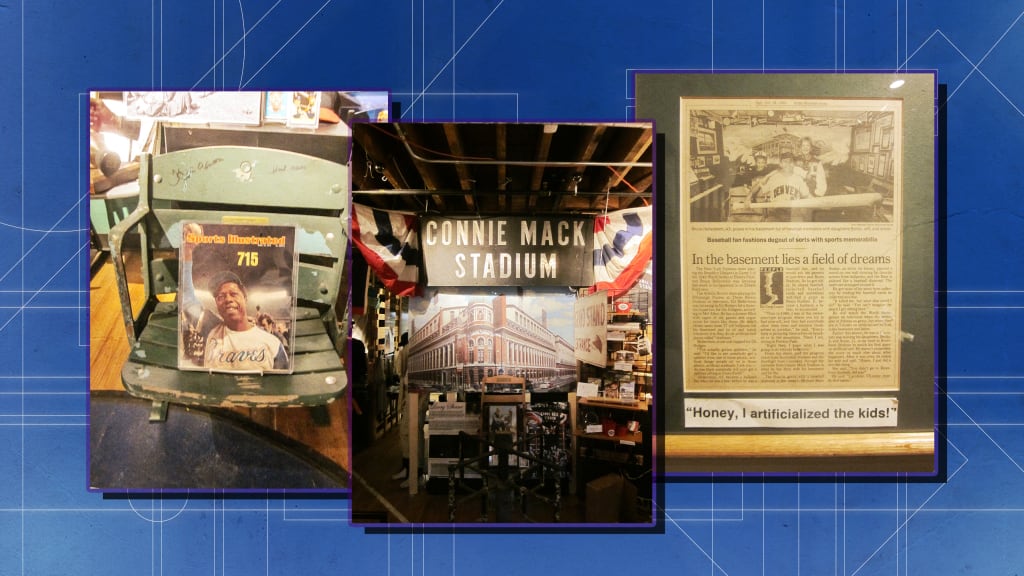

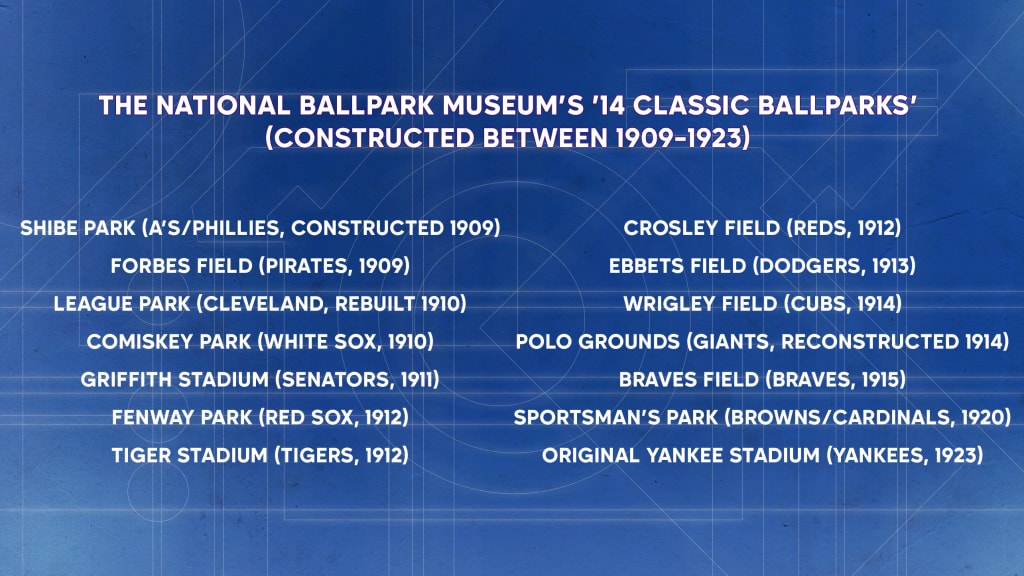

As soon as you walk into the museum, you're met with touchstones from what Hellerstein refers to as the "14 classic ballparks," defined as being built between 1909-23. You walk through the turnstiles from Philadelphia's Shibe Park -- built in 1909 -- before coming across one-of-a-kind pieces from Ebbets Field's marble rotunda, featuring a baseball chandelier and globes in the shape of baseballs. There's a piece of the architectural facade from the third deck of the original Yankee Stadium. It's one of what may only be two pieces left in existence -- and no one knows where the other resides.

"It's probably in someone's closet -- if it even exists, really," Hellerstein admits.

So, just how does a person go about creating a museum devoted to the ballparks themselves? For Hellerstein, it's what he fell in love with as a child.

"It's like no other place on Earth, being in an old ballpark -- just the sense of the game and the neighborhood. And it's so different from anything else in sports," Hellerstein said.

A third-generation Denver native, Hellerstein grew up a Denver Bears fanatic, the biggest baseball team in Colorado history before the Rockies moved in. The Bears were regularly atop their division, and Bears Stadium -- as it was called before eventually becoming Mile High Stadium -- could regularly sell out its 20,000-seat capacity. So many fans would attend the exhibition games that Cleveland and the New York Giants staged that they'd have to extend seating onto the warning track.

It was a second-grade show and tell when he first realized he loved the baseball cathedrals a little more than his classmates.

"There was a girl that said, 'I went to Bears Stadium to see the Denver Bears,'" Hellerstein remembers. "Well, I was more excited to see Bears Stadium than the Denver Bears. I had to see this place. And I was always intrigued with ballparks. I would ask Denver players, 'What was it like playing in Oklahoma City? Indianapolis? What do these places look like?'"

(It shouldn't be surprising, then, that the museum has a room devoted to the Bears. "I don't mean to brag, but we have the best collection, we have the rarest stuff that exists. It's a very, very special room," Hellerstein said.)

It would take a few decades and a personal development class for Hellerstein to fully realize his life's goal. While others were perhaps dreaming of expensive yacht trips around the world, Hellerstein had a much different idea.

"They had a session, with the music and everything, where you visualize your perfect paradise," Hellerstein said. "No oceans or mountains -- mine was all ballparks. So, that gave me the idea -- because our basement was unfinished -- to create a museum in my basement. That's where it all started."

So, if you were in Denver in the mid-80s and knew where to look, you could head to Hellerstein's basement where, instead of the usual furnishings like old leather couches or a pool table, you'd enter "The Ballpark Room." With the floor painted to look like a baseball field and with assorted other memorabilia, you'd find seats from all 14 of the classic ballparks -- something you'll still find when you walk inside the museum in its new digs today.

"In the IRS world, it's unheard of to have a public museum in your home," Hellerstein said with a laugh, showing off his professional bonafides. "The IRS doesn't like those sort of things. They want real museums, not just in name only."

So, in 1999, as his collection expanded, he opened the museum in a new space, becoming a charitable non-profit organization along the way. No longer housed in his basement, now it was located just a stone's throw from Coors Field -- with Hellerstein's office located in the back rooms. (As the museum has continued to grow, Hellerstein has left for a nearby space, no longer doing his work next to his cherished memorabilia.)

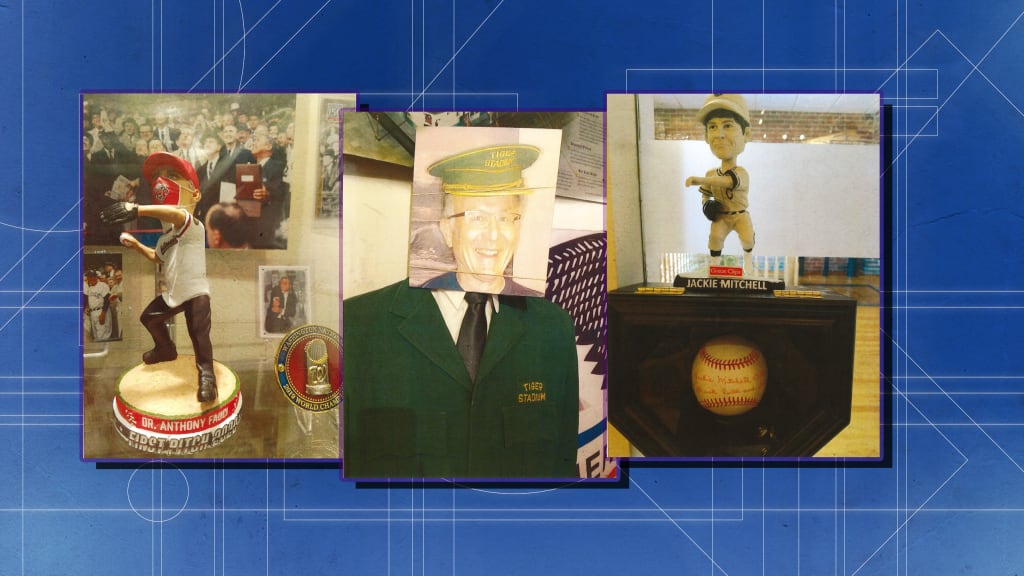

Beyond the 14 seats taken from the original location, the museum has the only full terracotta pieces that framed the outside of Forbes Field in the storefront windows. There are scoreboards and ushers uniforms, the cornerstone of Griffith Stadium -- a big, heavy bronze piece -- along with artwork celebrating the history of these magical places.

The museum may be dedicated to the stadiums, but it doesn't ignore what happens on the field, either. There are pennants and uniforms from teams -- both Major and Minor -- throughout baseball history. There are baseball cards and autographs, bobbleheads ranging from Jackie Mitchell to Dr. Fauci and -- befitting his day job -- Babe Ruth's 1932 tax return. There are even bronzed hands of famous big leaguers made by sculptor Raelee Frazier, herself a museum volunteer.

"We celebrate Stan Musial and Ted Williams and Mickey [Mantle] and Hank [Aaron] and Willie [Mays] and Ernie [Banks] -- all the greats here," Hellerstein said. "Just the biggest thing is we're celebrating our national pastime."

While he's worked hard to put together a collection unlike anyone else's in the world, there are still a few things he won't touch.

"When they tore down Tiger Stadium in Detroit, getting urinals was a big collectible," Hellerstein said. "I don't quite take it to that extreme."

While Hellerstein may be obsessed with ballparks built more than 100 years ago, he knows that the stadiums are nothing without the people that fill them. It's a big part of why he loves these old parks, which were nestled into cramped city streets and whose outfield walls required all sorts of odd angles to work. They were simply a part of the community.

"I mean, if you took Wrigley Field and stuck out in the middle of the suburbs, it's not the same thing," Hellerstein said.

He's heartened to see the crowds coming to the museum, the young fans whose eyes light up when they walk through the cramped spaces and see the history that's around them. He knows they're falling in love with the same thing that captured his heart all those years ago.

"The mission of the museum is to keep the torch going for our national pastime, and very specifically the youth -- getting them just more and more exposed to baseball," Hellerstein said. "I've dedicated my life and my savings to this stuff. ... It's being third-generation, made-of-Denver -- this is my city and my community."

He points out that after turning the museum into a non-profit, the collection no longer belongs to him.

"But it belongs to the community, and so it has a life of its own," Hellerstein said. "That's the mission here, and it's getting that message out to the youth of this country: It's in their hands to keep this thing going."