A version of this story was originally published in April 2021.

As Shohei Ohtani renewed and expanded his rare role as a true two-way player for the Angels in 2021, the Babe Ruth comparisons began anew.

The Bambino is a big and therefore easy legend to latch onto. But now that Major League Baseball is officially recognizing the Negro Leagues as Major Leagues, the various bits of two-way trivia linking those two players -- fun though they may be -- are no longer historically accurate.

To draw a direct line from Ruth to Ohtani is to ignore the rich history of Negro Leaguers who were two-way topliners.

“For me, the excitement of Ohtani creates the exact opportunity we have today, to say, ‘Nah, it’s not just Ruth,’” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. “Maybe this will put the spotlight on those legendary players that people did not know.”

Major League Baseball is working with the Elias Sports Bureau to determine the best way to blend the available Negro League numbers with the data we’ve long had on hand from MLB, and that process is not yet finished. But when it is, the official records will be newly replete with players who shined in every facet of the game.

Due to financial limitations, Negro League teams were typically comprised of only 18-20 roster spots, and so it was commonplace for players to both pitch and play the field.

“The Negro Leagues consisted not only of league games but barnstorming games,” says official MLB historian John Thorn. “The need to have a reserve team often meant that everybody got to play everything.”

For Ted Radcliffe, who played in the Negro Leagues from 1929 to 1946 as a pitcher and catcher, playing both ways was not just a role but a brand. In a 1932 doubleheader between his Pittsburgh Crawfords and the New York Black Yankees at Yankee Stadium, Radcliffe hit a grand slam and caught the great Satchel Paige’s shutout in the first game, then threw a shutout of his own in the second. Renowned writer Damon Runyon saw the performance and dubbed him “Double Duty” -- the moniker Radcliffe, one of the Negro Leagues’ most lively ambassadors, would proudly wear for the rest of his 103 years.

“Duty was masterful,” Kendrick says. “He was a great character, a great promoter and a great storyteller. But sometimes lost in the character is the fact that he was one helluva baseball player.”

There were other great Negro League pitchers who could handle a bat, including Hall of Famers Ray Brown and Hilton Smith.

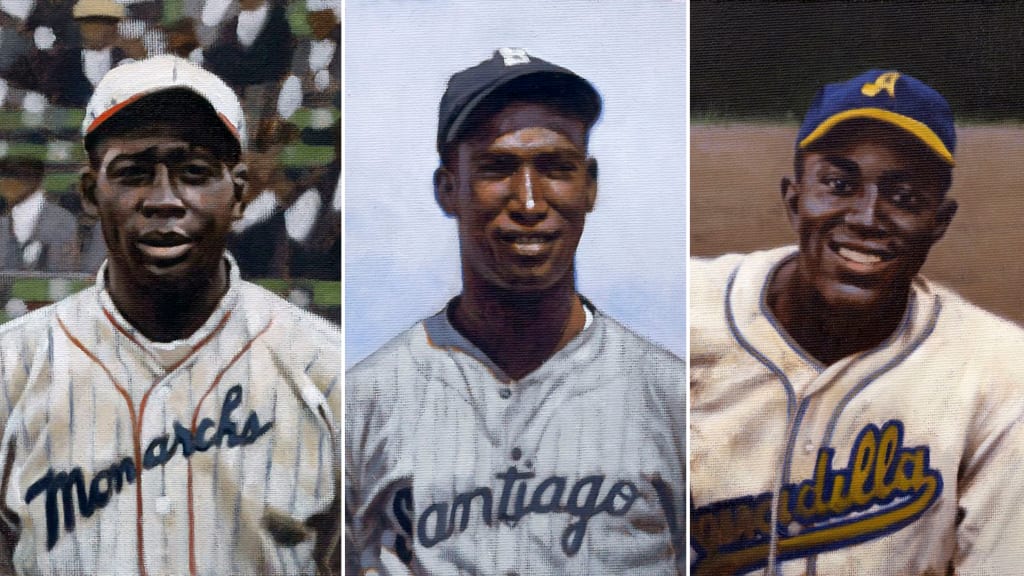

But if the goal is to center on true two-way greatness, then three Negro Leaguers stand out among all others. Though they all have a spot in Cooperstown’s hallowed Hall, their names are hardly household.

So as we embrace the Negro Leagues as a big league-worthy brand of baseball, let’s give these three amazing athletes their due.

“Bullet Joe” Rogan

Had he gone by his given name, Charles Wilber Rogan still would have been a great ballplayer. But the “Bullet Joe” moniker -- born out of Rogan’s blazing fastball -- provides an added mystique.

Same goes for the words of contemporaries like the late catcher Frank Duncan, who caught both Rogan and the legendary Satchel Paige and concluded, “Bullet had a little more steam on the ball than Paige, and he had a better-breaking curve.”

That’s a high endorsement. And per the data collected for the Seamheads database, Rogan put his stuff to good use with 130 wins, a 2.66 ERA and a 142 ERA+ (or 42% better than the league average) in 228 games (167 starts) over 15 seasons with the Kansas City Monarchs. Such pitching productivity is enough to earn Rogan a place alongside Paige and “Smokey Joe” Williams in the conversation about the best Negro League pitchers of all time.

But Rogan, who stood a small but strong 5-foot-7, 160 pounds, added to his allure with his reputation as a superb defensive center fielder and a fantastic hitter with a particular talent for doing damage with the low ball. The offensive stats compiled by Seamheads credit Rogan with a .336/.409/.510 slash, a 155 OPS+ (or 55% better than league average), 51 homers, 111 doubles, 60 triples and 111 stolen bases in 728 games.

Though we don’t know for certain, the best guess is that Rogan was born in July 1893, which means he would have turned 27 years old during the Negro Leagues’ first season in 1920. This came after Rogan had served in the Army and been the best player on the 25th Infantry Wreckers and after he had traveled with the All Nations team, a racially and ethnically diverse barnstorming ballclub that traveled the Midwest in the 1910s.

In other words, Rogan had some years under his belt by the time the Negro Leagues got going.

But that didn’t stop him from becoming, along with Oscar Charleston, one of the Negro Leagues’ first superstars.

“Rogan was the quintessential two-way player,” Kendrick says. “He had perennial 20-game winning capabilities. And when he wasn’t pitching, he hit cleanup and played the outfield and led the Negro Leagues in stolen bases when he was 38 years old.”

Some of Rogan’s season stat lines are comically good. In 1924, for instance, he went 18-6 in 203 innings as a pitcher while batting .386 with a 1.000 OPS in 206 plate appearances and leading the Monarchs to the first Negro World Series title.

As Paige once said, while taking delightful liberties with the limits of the dictionary: “He was the onliest pitcher I ever saw, I ever heard of in my life, was pitching and hitting in the cleanup place.”

The one and “onliest” Bullet Rogan passed away in 1967, 31 years before he was voted into the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee. Prior to his death, having settled in Kansas City, he spent 23 years working for the United States Post Office -- an unlikely place to find one of the greatest baseball players of all time.

Martín Dihigo

The bloated size of the modern bullpen has made positional versatility more valued than ever at the Major League level. So if Dihigo were playing today, he would undoubtedly be a hot commodity.

Seamheads’ database credits Dihigo with no fewer than 235 innings apiece at first base, second base, shortstop, third base, left field, center field and right field in a professional career that spanned 1922 to 1945.

What about catcher, you ask? Well, Dihigo caught six innings in 1929 in the American Negro League, so he briefly covered that one, too.

“You could play him anywhere,” Thorn says. “The one place you didn’t want to play him was catcher because of the risk of injury. You didn’t want to lose him for any length of time.”

And, yes, Dihigo also pitched -- 973 2/3 innings that we know about in the Caribbean and Mexican winter leagues and 459 1/3 innings in the Negro Leagues, per the Seamheads research. He had a 3.28 career ERA to go with his .312 career average and .916 OPS as a switch-hitter.

No wonder Dihigo was known as “El Maestro,” or “The Master.”

“I’m not sure there’s another player in history that matches Dihigo’s versatility,” Kendrick says. “He played every position and played them all well. He was extraordinary.”

How extraordinary? Dihigo is in five different Halls of Fame -- in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico and, of course, Cooperstown, where he was inducted in 1977, six years after his death.

Born in Cuba in 1905, Dihigo was raised in a baseball culture where it was not uncommon to move around the diamond. In playing year-round, he developed into a graceful player with a tremendous feel for the game and movie-star good looks. He was tall and fast with a powerful right arm capable of retiring batters when he was pitching and runners when he was in the outfield. He was also beloved by his teammates because he was fluent in both English and Spanish and had so much knowledge to share.

Though he began to pitch less frequently as his Negro League career evolved, Dihigo remained a regular on the mound in the winter leagues, tossing the first no-hitter in Mexican League history in 1938. As if his versatility in the field weren’t enough, Dihigo even served as a player-manager for the New York Cubans of the Negro National League in 1935 and 1936.

“El Maestro” finally retired at the age of 41, but by then he had earned another nickname -- “El Inmortal,” or “The Immortal One.”

“He was the best ballplayer of all time, Black or white,” Negro League legend Buck Leonard once said. “You take your Ruths, Cobbs and DiMaggios. Give me Dihigo, and I bet I’d beat you almost every time.”

Leon Day

The story, as Day once told it, is that when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers’ farm club in Montreal in 1946, he asked Day to join him. Day had just completed his Army service in the 818th Amphibious Battalion and had signed a contract to return to the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, so he turned down Robinson’s request.

Whether that tale is true or apocryphal, we know that Robinson and other Negro Leaguers at that point in time certainly held Day in high esteem. His unusual no-windup delivery made him a deceptive and difficult pitcher to face, and his great athleticism made him an asset at second base and in center field.

Day was the last of the great two-way Negro Leaguers.

“He was something to behold, on the mound or in the field,” Day’s Newark Eagles teammate Monte Irvin once said. “He played center field as good as, or better than, the starting center fielder did.”

Irvin should know. He was the starting center fielder.

Another Hall of Famer and Newark teammate, Larry Doby, considered Day to be the Negro Leagues’ finest pitcher at the time.

“Day could throw as hard as anyone,” Doby once said. “If you want to compare him with Bob Gibson, Day had just as good stuff. Tremendous curveball and a fastball at least 90 to 95 miles an hour. You talk about Satchel... I didn't see anyone better than Day."

Born in 1916 in Alexandria, Va., Day’s Negro League career began with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1934. He basically flung the ball from his ear, an odd short-arm offering inspired by the way he’d whip the ball to first as an infielder. Day’s shoulder gave him fits when he tried to throw overhand, so he invented his own way to pitch.

“I couldn’t throw overhand, so I jerked it at them,” Day once said. “It fooled a lot of hitters.”

Day’s bat was a little slower to develop than his pitching. But by the time he joined Newark in 1936, he was the total package. Though his Negro League career was interrupted by his contribution to the World War II effort, he played 10 Negro League seasons, along with various stints in Mexico, Cuba, Canada, Venezuela and Puerto Rico. He pitched in a record seven Negro League All-Star Games and also set a Negro League record with an 18-strikeout performance in a one-hitter in 1942. In his first start for Newark after the return from the war, he threw a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars.

By the time organized baseball was willing to acknowledge Day’s talent, he was in his mid-30s. He played three seasons of affiliated Minor League ball from 1951-53, but his dynamic days were behind him. He never got the Major League opportunity his talent deserved, and his Hall of Fame entry came much later than it should have. Day was voted in by the Veterans Committee on March 8, 1995, when he was 78 years old. He was elated by the news.

“I’m so happy, I don’t know what to do,” he said at the time. “I never thought it would come.”

Day passed away just five days later, so he never got his day in the sun in Cooperstown that he deserved.

He deserves this much, too: When we say Shohei Ohtani is the best two-way player since Babe Ruth, what we should really be saying is that he’s the best two-way player since Leon Day.