Discover the mysterious origins of some of baseball's most well-known terms

Last year, we brought you the wild and winding stories behind some uniquely strange bits of baseball slang. For example: Did you know that Dennis Eckersley coined the term "walk-off" just months before serving up this walk-off?

Here's the thing, though: Baseball has a lot of uniquely strange baseball slang. Like, two centuries worth -- and wherever there are weird words, there are even weirder explanations for them. Let's go down the rabbit hole together.

Naturally, the accepted terms for the next two batters in the order draw inspiration from ... [squints at cue card] the interior of a ship?

Yes, like a sailing ship. As you can probably guess, to be"on deck" was to be in the main area of ship, aboveboard, and to be "in the hold" was to be in a holding place below deck. There's some speculation that the termspicked up in popularity after WWII, perhaps due to association with aircraft carriers, where pilots waiting their turn to take off would be "in the hold."

No one's quite sure how "in the hold" became "in the hole," though the association with "fire in the hole" is a pretty appropriate one:

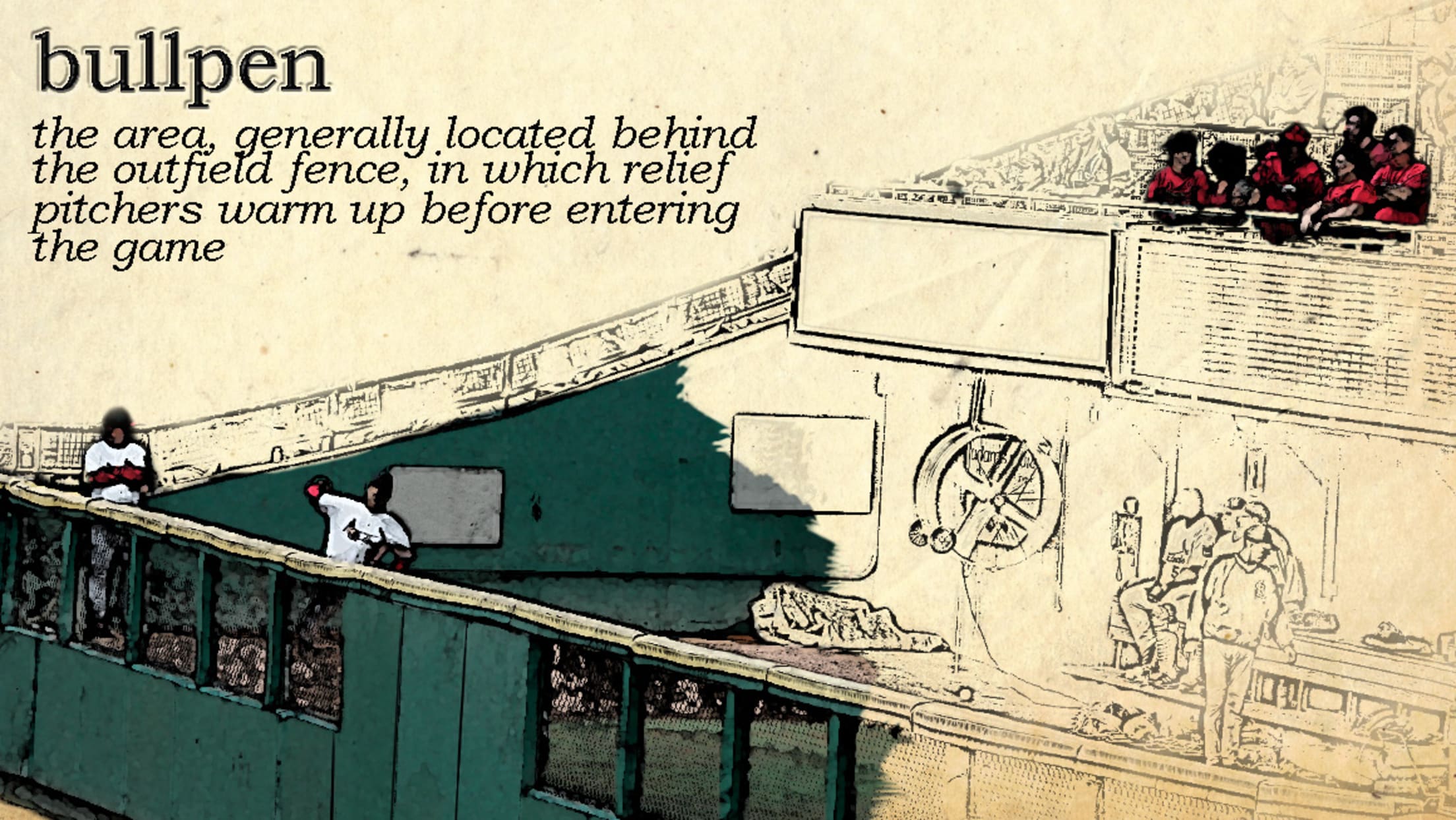

Surprisingly enough, the history of "bullpen" as it's used in baseball is unclear. That certainly hasn't stopped baseball fans and historians from trying to understand it, though, and they've concocted some truly excellent theories over the years. A brief rundown:

- It's a reference to the pen in which rodeo bulls were held before being released into the ring.

- The term comes from 19th century holding cells, which were often called bullpens -- inspired by the bullish features of police officers.

- Legendary Giants announcer Jon Miller once claimed that it originated in the Polo Grounds, where relief pitchers warmed up near a stockade just behind the left-field fence.

- In perhaps the single most Casey Stengel anecdote of all time, Stengel suggested that it was actually managers who came up with the term. Tired of listening to relievers "shoot the bull" in the dugout, the theory went, skippers decided to send them off beyond the outfield fence where they couldn't be a distraction.

Our personal favorite, though, involves tobacco advertising. Outfield fences in the 19th century often featured ads for Bull Durham tobacco -- though sadly, not all of them came with the promise of a free steak:

Since relief pitchers warmed up in a pen nearby, the name was born.

"Shortstop" is such an everyday part of the game that you might never have stopped to think about what the heck it actually means.

According to MLB official historian John Thorn, the position was created by Doc Adams, member of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, one of the game's founding fathers and the owner of one heck of a beard:

At the time, baseball wasn't a nine-man game -- the only things required to field a team were a pitcher, a catcher and a defender at each base, with surplus players being placed in the outfield.

This created some fielding issues, however. The earliest baseballs were handmade and very light, and it was nearly impossible to throw them any significant distance -- like, say, from the outfield to the infield. So Adams had an idea: Position a fielder in the "short field," or shallow outfield, to help get the ball back into the infield more quickly and efficiently. Since most throws from the outfield came toward third base or home plate -- and most batters pulled the ball -- it only made sense for him to stand on the left side of the diamond.

As baseballs became harder, they were capable of being both hit and thrown farther, allowing the new "shortstop" to move into the infield.

These days, "hat trick" is more commonly associated with hockey, but its origins actually lay in cricket: After famed English bowler H.H. Stephenson took three wickets (outs, basically) on three consecutive pitches, adoring fans held a fundraiser in his honor and bought him a hat with the proceeds. Since early baseball shared much of its DNA with cricket, it was only natural that the term would extend to batters striking out three times in the same game.

"Golden Sombrero," on the other hand, is purely baseball's creation. The thinking was simple: What's grander than a hat? Not just a sombrero, but a golden one. Legend has it that the term was coined by former Padres outfielder

What we do know is that strikeout slang hardly stops there. Five strikeouts in a game is a platinum sombrero -- or, if you're feeling a bit more inspired, an "Olympic rings." Six strikeouts in a game, however, is where things start to get really fun. Believe it or not, there's an actual name for this extremely rare event: a Horn, as in former Orioles slugger Sam Horn, who whiffed six times against the Brewers back in 1991.

At the time, Horn was believed to be the first non-pitcher to, er, "accomplish" the feat, so teammate Mike Flanagan decided to name it after him. Alas, if only Sam had known that he wasn't alone: At the time, five other big leaguers were members of the six-K club, and in the years since, two more have joined them. The most recent instance? Geoff Jenkins, in a game against the Angels back in 2004.

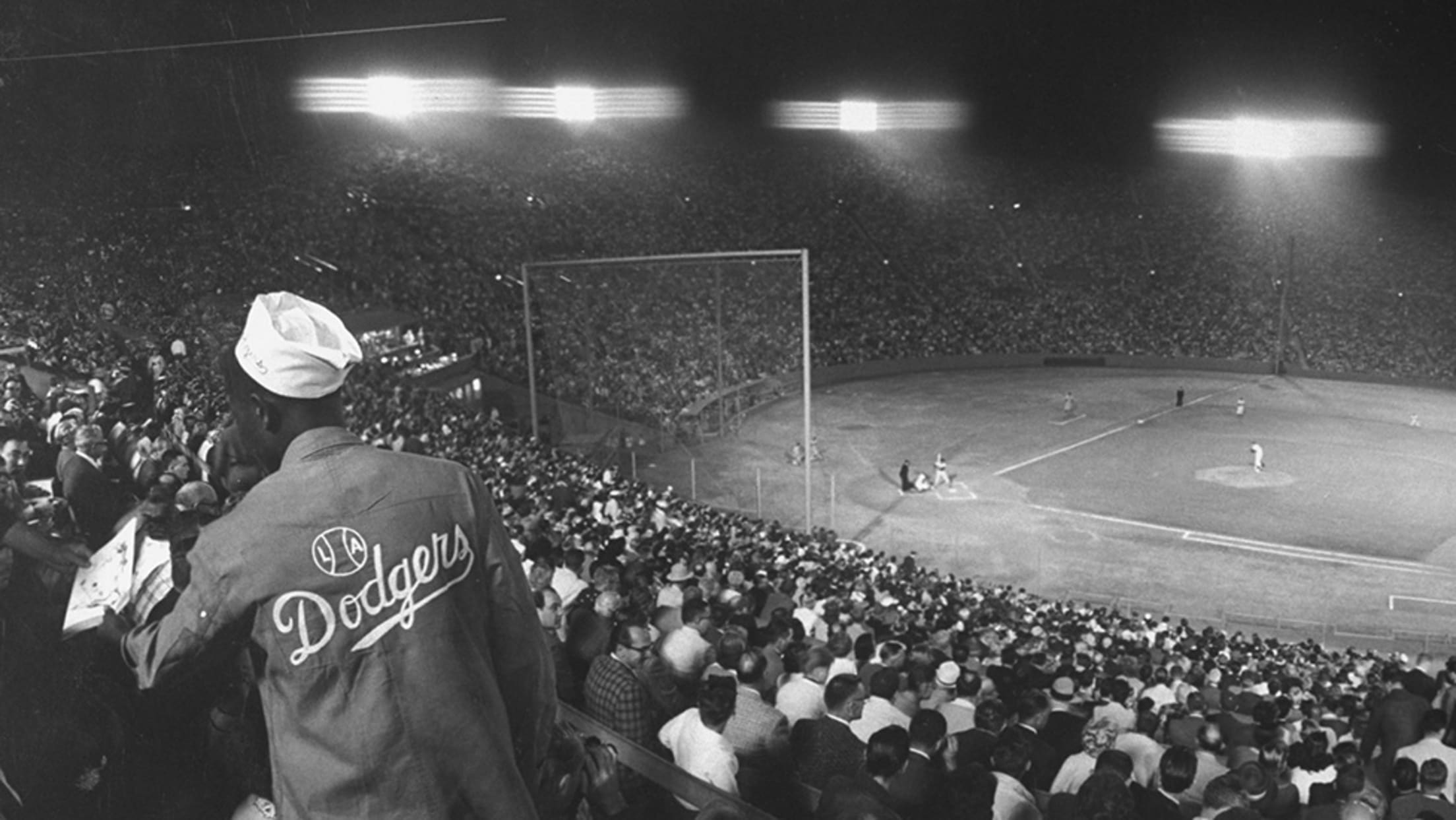

When the Dodgers decided to move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles at the end of the 1956 season, they did so without any idea where they'd play when they got to the West Coast.

The ballpark of owner and real estate tycoon Walter O'Malley's dreams was a massive undertaking, one that wouldn't be complete until Dodger Stadium officially opened in 1962. So, in the meantime, the team needed a temporary home -- and, after some searching, it finally settled on the Los Angeles Coliseum. The Coliseum, as you may have heard, was not designed with baseball in mind. Which was how you ended up with this:

No, that's not a mirage: The Coliseum's left-field foul pole was just 250 feet (!) away from home plate. Just how does the term "moonshot" play into this, you ask? While pitchers hated the new dimensions -- it even inspired Warren Spahn to personally lobby for a new rule stipulating that home runs had to travel at least 300 feet -- batters quickly learned to adapt. One hitter in particular embraced his new home park: Dodgers lefty Wally Moon changed his swing dramatically to hit high fly balls to the opposite field, inspiring local journalists to dub them "moon shots."

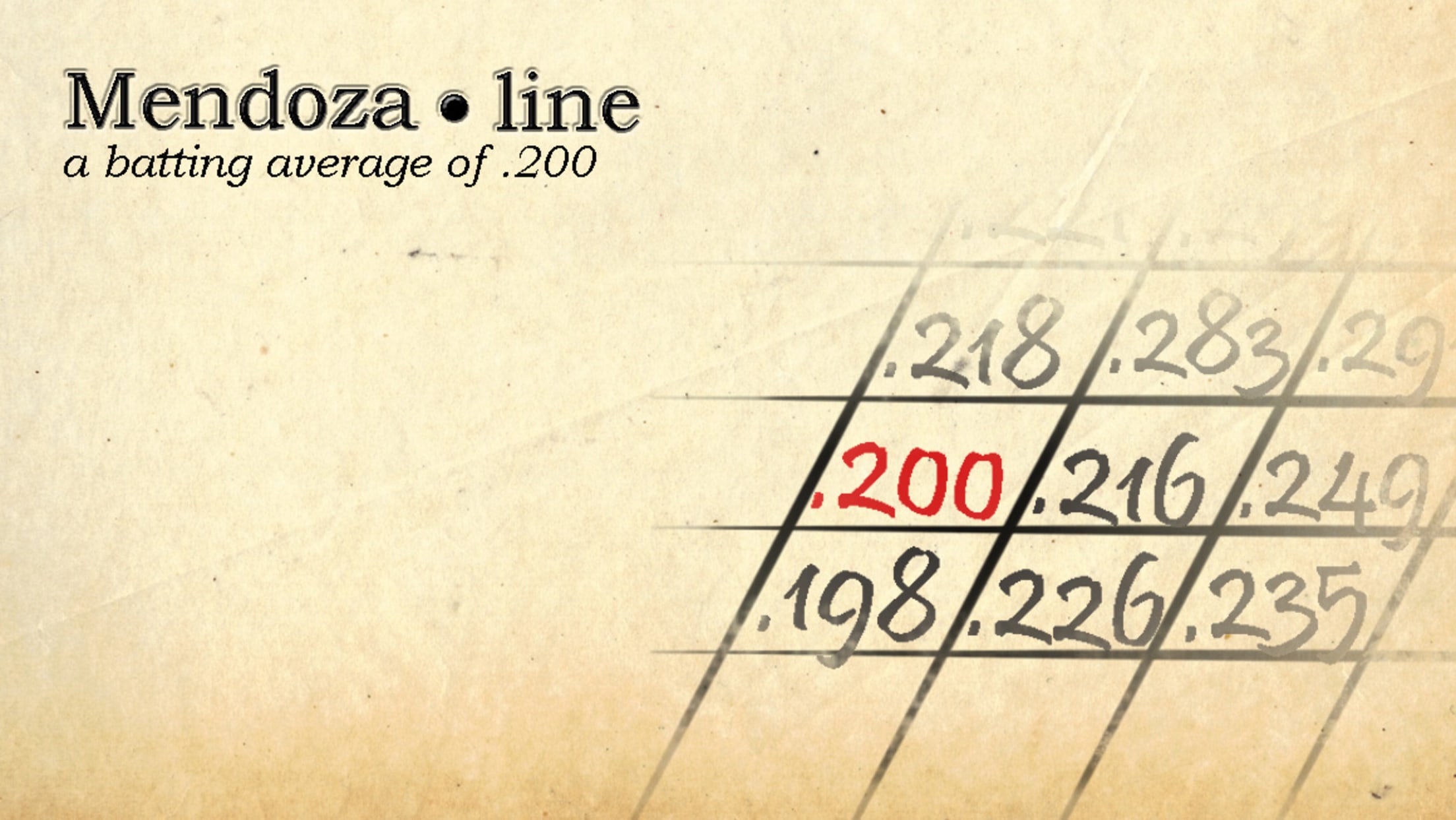

Over a nine-year Major League career, Mario Mendoza was a solid defensive shortstop for the Pirates, Mariners and Rangers. His bat, however, was ... well, it wasn't great: Mendoza was a lifetime .215 hitter, and from 1975-79, he finished below .200 four times -- a mark that became known as the Mendoza Line. He was, however, a fearless advocate for all those who wished to play baseball in glasses, and for that he has our undying respect:

Credit for inventing the Mendoza Line is generally given to George Brett. In a slump early in the 1980 season, the Hall of Famer told reporters, "The first thing I look for in the Sunday papers is who is below the Mendoza line." Brett eventually mentioned the term to ESPN's Chris Berman, and from there, it spread like wildfire -- eventually becoming a universally recognized shorthand for batting futility.

Here's the thing, though: According to Mendoza himself, Brett isn't the one who came up with the idea. As he told STL Today in an interview:

"My teammates Tom Paciorek and Bruce Bochte used it to make fun of me. Then they were giving George Brett a hard time because he had a slow start that year, so they told him, 'Hey, man, you're going to sink down below the Mendoza Line if you're not careful.'"

Paciorek and Bochte played with Mendoza on the 1979 and 1980 Mariners, and as the shortstop's average continued to fluctuate around the .200 mark, they came up with the line as a way to rib their teammate.

Ironically enough, Mendoza's 1980 campaign was the best of his career: He finished at .245 with a career-high two home runs and .596 OPS. He would get the last laugh, though, enjoying a long and successful career as a manager in both the Minor Leagues and Mexico before being inducted into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.

Technically, the original term was "banjo hit," a phrase similar to "Texas Leaguer," used to describe soft contact that fell in for a hit. Jersey City Skeeters second baseman Ray "Snooks" Dowd first coined it back in 1925, because the sound of the ball coming off the very end of the bat "plucked" like a banjo.

From there, "banjo hitter" grew to encompass any batter who didn't have much power or ability to make hard contact. This wasn't necessarily a derogatory term -- it was sometimes used to describe contact hitters like Bert Campaneris.

Still, for the most part, it was a label you definitely wanted to avoid. Perhaps baseball's most famous banjo hitter? Michael Jordan: "The woods are full of banjo hitters," the Sporting News' Dave Keating wrote as MJ left baseball to return to the Chicago Bulls. "But Jordan's leaving is important for what it says about baseball."

Around the turn of the 20th century, "the bush" was a common slang phrase for rural areas, similar to "the sticks" or "the boondocks." Lower-level Minor Leagues, usually "out in the bushes" in sparsely populated towns, were known as "bush leagues."

The players who participated in bush leagues were looked down on by their Major League counterparts, who saw them as a mix of boorish amateurs and washed-up veterans -- crude on and off the field. William Patten and J.W. McSpadden's "The Book of Baseball" wrote of the bush leagues' "sadness of cheap hotels, rancid food and fetid dressing rooms; of inferior craftsmanship and memories of gone glories."

Once this reputation calcified, "bush" and "bush league" became a catch-all for anything that was seen as unbecoming of a big leaguer. Not even Red Auerbach himself was safe: Elaborating on why longtime White Sox pitcher Johnny Rigney repeatedly referred to him as "bush," Auerbach once wrote, "You might have been an All-American with nine degrees, but if you weren't a big league baseball player, they all called you 'Bush'."

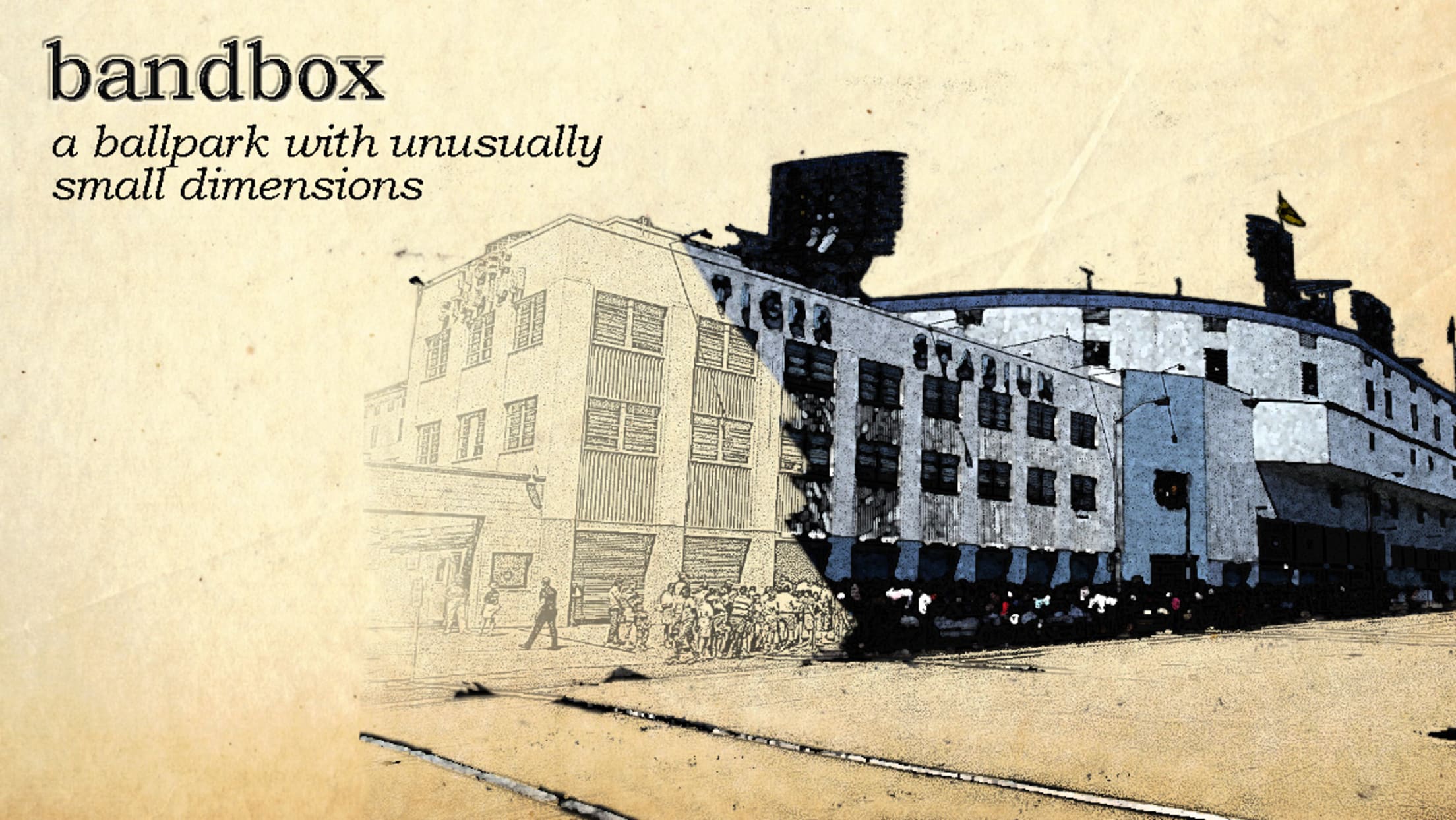

When AJ Reach and John Stone won the rights to an expansion National League franchise in Philadelphia in 1883, they immediately set about looking for a brand new ballpark to go with their brand new team. After four seasons, the Baker Bowl finally opened -- an $80,000, 12,500-seat modern marvel, one of the crown jewels of the dead ball era.

There was just one problem: Philly's grid system was well-established by that point, and the park had to be shoehorned into a small city block. And we do mean small. As a matter of necessity, the right-field fence was a mere 280 feet away, and right-center wasn't much better at 300.

The team tried to alleviate the pressure those dimensions put on pitchers, leaving acres of foul territory all around the park. It even led them to construct one of the park's iconic features: the Baker Wall, a towering portion of the right-field fence that stood 60 feet tall -- 23 feet higher than the Green Monster -- in its final iteration.

Alas, none of it worked. Exacerbated by a pitching staff that was, to put it lightly, not very good -- the Phillies of the Baker Bowl era went a long way toward the franchise reaching the 10,000-loss milestone back in 2007 -- home runs left the park at an alarming rate once cork-centered balls were introduced in 1911. As Fred Lieb and Stan Baumgartner wrote in their history of the team: "Writers with other clubs constantly were poking fun at the Philadelphia home run crop, and blaming it on the small Philadelphia ball park."

This being Philadelphia, the nicknames soon followed. First was "The Cigar Box," but soon fans settled on something more appropriate to the Baker Bowl's rounded shape: "The Bandbox," named after the circular hat boxes of the day.