Baseball's butterfly effect: Small moments that forever changed MLB history

In 1961, meteorologist Edward Lorenz entered a microscopically different value into his computer model -- .506 rather than .506127 -- and discovered that it had drastically altered the results of his weather prediction. His subsequent paper titled, "Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?", officially coined the term "the butterfly effect": the theory that small events can have significant consequences.

Which brings us to baseball. You could tell the game's story in a handful of iconic moments: the end of the dead-ball era, Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier, the Shot Heard 'Round the World. But so much of MLB history was set into motion on a much smaller scale -- some fortuitous timing here, a seemingly innocuous decision there, and some of baseball's greatest careers and memories were born.

Wally Pipp's headache

What better place to start than with the man whose name became a verb? It's worth noting that Pipp had a very solid career with the Yankees -- he was acquired in 1915, when the Bombers had posted just one winning record over the past eight seasons, and immediately stabilized the middle of the New York lineup. He led the league in home runs twice, and with the help of some guy named Babe Ruth, he helped the Yankees capture their first World Series title in 1923.

In the midst of all that production, Pipp even helped out New York's scouting department. In particular, one player caught his eye: a first baseman with prodigious power from just down the road at Columbia University. Pipp liked him so much that he told his manager, Miller Huggins, to sign him -- and just a month later, Lou Gehrig was a New York Yankee.

Of course, at the time, Gehrig was still just a relatively unknown prospect, while Pipp was an established veteran. That is, until June 2, 1925, when Pipp came to the ballpark a little under the weather. As the legend goes, he had a headache that he just couldn't shake -- possibly from being hit in the head by a pitch a couple games prior -- and asked the team trainer for a couple aspirin. Huggins overheard, and he decided to pencil his young backup in the lineup.

Contrary to popular belief, that wasn't the beginning of the Iron Horse's legendary games played streak -- that came the day before, when he registered a pinch-hitting appearance against the Senators. Still, Gehrig finished the year hitting .295 with 20 homers, and the Murderers' Row Yankees never looked back. As for Pipp, he was later hospitalized with double-vision related to the incident and ended up with a .230 average and just three homers on the season. The Yankees put him on waivers that winter, and he was claimed by the Reds, where he played the final three seasons of his career.

Aaron Boone plays an ill-fated pickup game

In the winter of 2003, Boone was on top of the world. Yes, the Yankees had fallen to the Marlins in the World Series, but the team only got there because its third baseman hit one of the most dramatic home runs in the history of the game. Perhaps you remember it:

Those postseason heroics, combined with a solid '03 campaign in which he launched 24 dingers, convinced the Yankees to hand Boone the third base job going forward. Entering a contract year with a full-time gig on a team that had been to six of the past eight Fall Classics, things were looking up. And then, he decided to play a game of basketball.

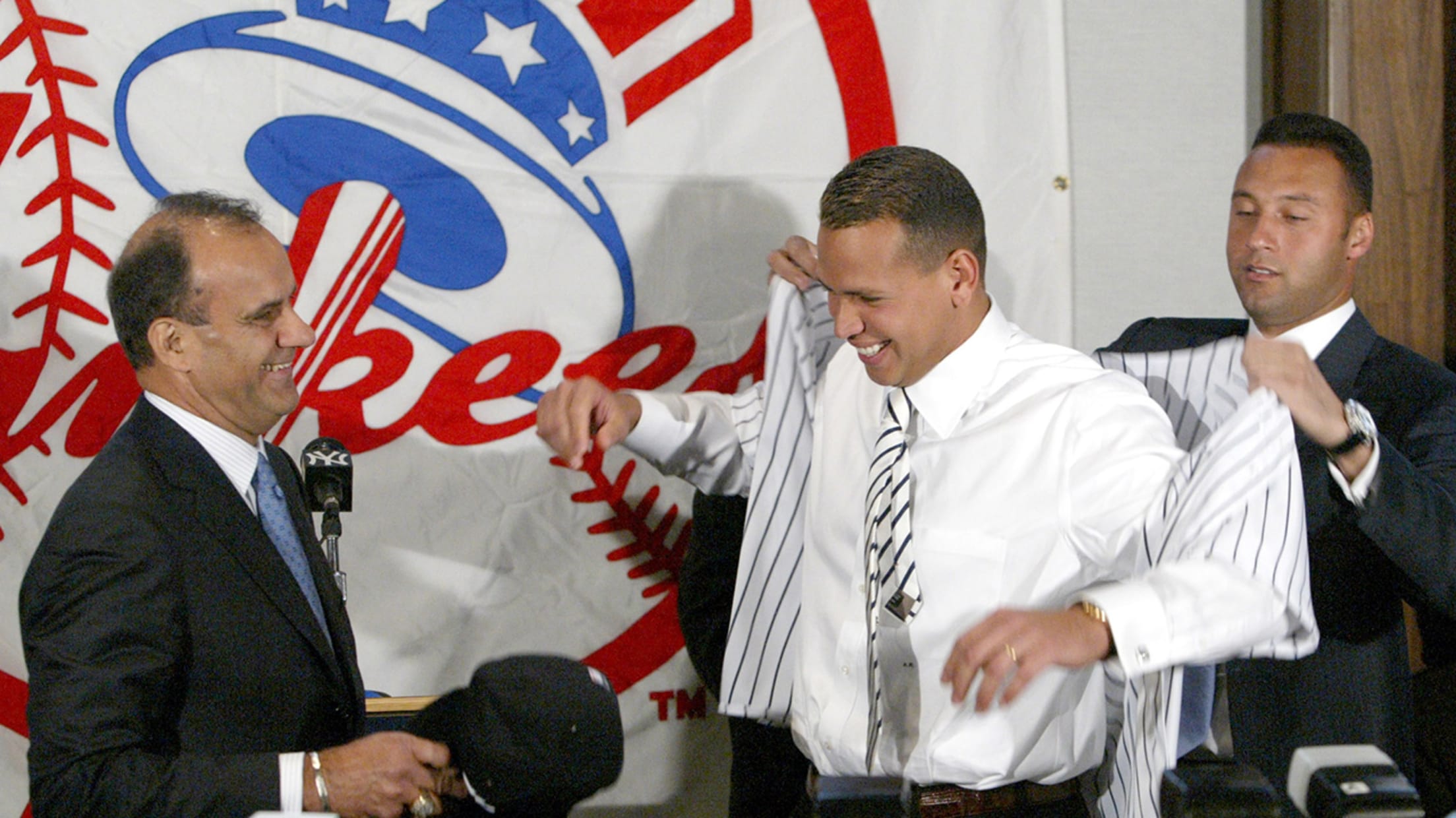

In late February, Boone tore his ACL in a pickup game, knocking him out for the year and violating the terms of his contract. The Yankees soon released him, which left them suddenly in the market for a third baseman. As it happened, a pretty good infielder was on the market:

If Boone stays healthy, who knows what happens? A-Rod almost certainly doesn't come to the Bronx, as the Yankees hadn't been linked to him in trade talks all winter. Without the reigning AL MVP, does New York reach the ALCS? Does Boston, desperate at the non-waiver Trade Deadline, ship Nomar Garciaparra to Texas, freeing up enough salary to get a deal done? Do the Yankees, weighing options at third base after Boone hits free agency, decide to stick a young infield prospect named

A fishing trip kept the DH from coming to the National League

Think of all the advancements in #PitchersWhoRake over the last couple of years. Think of the bat flips, the walk-offs and that rarest of unicorns -- the Bartolo dinger. And now, let this sink in: We have an exceedingly poorly timed vacation to thank.

Allow us to explain. In the years following its adoption of the designated hitter in 1973, the American League saw a distinct increase in offensive production -- and, as a result, a distinct increase in attendance. So, in 1980, the Senior Circuit put it under consideration. The NL was to hold a yes/no vote on Aug. 13, with a simple majority of the 12 teams necessary for the rule to be approved. This is when things went improbably, hilariously off the rails.

Pirates GM Harding Peterson entered the meeting with very straightforward instructions: Vote as the Phillies voted. As for Philly, team owner Ruly Carpenter -- on the left in the photo above -- told his vice president, Bill Giles, to vote for the DH. The reason for this was simple: Philly had Greg Luzinski in left field with young Keith Moreland searching for playing time, two strong bats who weren't particularly skilled in the outfield.

That weekend, Carpenter decided to go fishing, confident that his right-hand man had things under control. That ... did not turn out to be the case. As the meeting began, teams were informed that the rule wouldn't come into effect until the 1982 season. Giles hesitated, unsure whether this new information would change his owner's thinking. And, given that this was the early 1980s, nobody could get a hold of Carpenter, so Giles was forced to abstain.

The final tally? Five against, four in favor and three absentions (including the Phillies and Pirates) -- exactly two yes votes shy of approval. Five days later, the Cardinals fired GM John Clairborne, one of the leading proponents of the rule change, and the NL hasn't held another vote since.

The flu that launched The Year of the Bird

Mark Fidrych began 1976 as an anonymous rookie, one of the last men out of the Tigers' bullpen. He ended 1976 as one of baseball's biggest sensations -- thanks to a very timely illness.

Nothing about Fidrych's pedigree suggested that stardom was imminent. After a stellar, if relatively quiet, prep career in Massachusetts, the Tigers selected him in the 10th round of the 1974 Draft, which came as such a surprise that Fidrych initially assumed he had been drafted into the military. After a solid year and a half in the Minors, Fidrych was a non-roster invitee to Spring Training in 1976, where he managed to make the team despite losing his only decision.

Still, he was basically at the bottom of Detroit manager Ralph Houk's totem pole. Through the first few weeks of the season, Fidrych had only been called on in relief twice, both in mop-up situations. That all changed on May 15.

Fidrych's roommate, Joe Coleman, was scheduled to start that day against the Indians. Unfortunately, though, he woke up with the flu, and managed to convince Houk to give his friend the nod. The rookie responded, retiring the first 14 Cleveland batters he faced, taking a no-hitter into the seventh inning in a 2-1 victory. Ten days later, Fidrych was given the ball again at Fenway Park, where he surrendered only a two-run homer to Carl Yastrzemski in another complete-game outing.

That was enough to convince Houk that Fidrych was worthy of a regular rotation spot, and the rest, as they say, is history: The righty reeled off eight straight wins, including consecutive 11-inning (!) complete games, and the legend of "The Bird" -- a term originally coined by one of Fidrych's Minor League managers, who noticed that his shock of curly hair made him look like Big Bird -- was born. Of course, the mound antics didn't hurt -- as the Sporting News documented just a month after Fidrych became a starter:

He talks to the ball. He talks to himself. He gestures toward the plate, pointing out the path he wants the pitch to take. He struts in a circle around the mound after each out, applauding his teammates and asking for the ball. And he's forever chewing gum and patting the dirt on the mound with his bare hand.

Fidrych was dominating and baffling in equal measure -- he was known to discard balls with which batters had gotten a hit, and routinely shooed away groundskeepers so he could landscape the mound himself -- and the country couldn't get enough. The sensation peaked in a June 28 start against the Yankees, featuring a 7-1 Fidrych against the first-place Bombers on ABC's Monday Night Baseball

A raucous 47,855 fans packed Tiger Stadium, with another 10,000 reportedly turned away before first pitch, and the Bird didn't disappoint -- he spun yet another complete game, giving up just seven hits in a 5-1 win. Fidrych finished the '76 season with a league-leading 2.34 ERA, taking home AL Rookie of the Year honors and finishing just behind Jim Palmer for the AL Cy Young Award. And if it weren't for Coleman's flu, who knows what would have happened?

What if Barry Bonds had listened to Andy Van Slyke?

The Pirates of the early 1990s are one of baseball's great "What ifs?" Led by three-time NL MVP Barry Bonds, Pittsburgh won three consecutive division titles from 1990-92 -- only to suffer three consecutive heartbreaking losses in the NLCS.

None of them were quite as heartbreaking as '92, though. Down 3-1 in the series, the Pirates stormed back to force a Game 7 in Atlanta and took a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the ninth behind ace Doug Drabek. And then, just three outs away from the team's first World Series appearance in 13 years, the wheels came off.

Jim Leyland decided to leave Drabek in to start the ninth, but behind a double, an error and a walk, the Braves loaded the bases with no one out. Leyland then turned to closer Stan Belinda, who got a sac fly and a pop out to bring Pittsburgh one out away -- with the winning run on second, in the form of the legendarily slow Sid Bream.

Francisco Cabrera lined a single to left field, and with Bonds forced to throw across his body, Bream just barely beat the ball to home plate. The Braves were headed to the World Series again, and wouldn't miss the postseason again until 2008. The Pirates, meanwhile, came undone -- Bonds and Drabek left in free agency, just as slugger Bobby Bonilla had the year before, and Pittsburgh didn't see postseason baseball again until 2013.

But what if things had gone differently? What if Bonds had been positioned differently in left field? What if his throw had been just a few inches closer to home, or arrived just a split-second sooner? It's a hypothetical that still haunts Andy Van Slyke. Van Slyke, Pittsburgh's center fielder, motioned for Bonds to move a few steps in for the light-hitting Cabrera, but Bonds simply waved him off and stayed where he was.

He turned and looked at me and gave me the international peace sign. So I said, 'Fine, you play where you want.'

Had Bonds heeded his teammate's advice, he certainly fields Cabrera's line drive more quickly, and there's a very good chance his throw gets Bream. The game goes to extras, giving the Pirates another chance to finally get over the hump and face the Blue Jays in the 1992 World Series. From there, who knows? Maybe Pittsburgh wins it all, nipping Toronto's dynasty in the bud before it even begins. Maybe the goodwill from a title run convinces Bonds or Drabek to stay. Bonds never goes to San Francisco, and baseball history is forever altered. If you think all that's hyperbolic, don't take our word for it -- just ask the guys at MLB Network:

The Yankees owe Mariano Rivera to a teenager's bad outing

When New York scouts first laid eyes on Mariano Rivera, he was a scrawny shortstop in Panama. The Yanks originally wrote him off, concerned about his lack of size -- he reportedly weighed around 150 pounds as a teenager -- and his ability to hit at higher levels. Luckily, though, the team would get a second look that changed everything ... just at a slightly different position on the diamond.

In the winter of 1989, Rivera's youth team, Panama Oeste, was participating in Panama's national amateur tournament. Things weren't going so well. Oeste's starter got roughed up early in the game, so early that Rivera -- who started the game at short -- volunteered to come on in relief, despite exactly zero experience as a pitcher.

And, amazingly, it went pretty well. He didn't have much of a fastball, but the great athlete with a smooth, simple delivery immediately shined through. A couple of Rivera's older teammates alerted New York's scouts in the area, and the Yankees decided to invite Mo to a tryout camp in Panama City two weeks later. Then-Director of Latin American Operations Herb Raybourn saw the teenager throw just nine pitches -- but that was enough to sign him for $2,000 on Feb. 17, 1990.

Which begs the question: What if Rivera's teammate had pitched pretty well that day? Would Mariano have ever had a reason to take the mound? Would he have simply been an infield prospect that didn't pan out? Thankfully, we don't live in that timeline.