These are the most unusual places that have hosted teams in Spring Training

When you think of Spring Training, two states immediately come to mind: Arizona and Florida. They have hosted the Cactus and Grapefruit Leagues for decades now, but it wasn't always that way. For a long time, there wasn't much consistency to where teams prepared for their seasons, and that inspired bold new ideas.

Some destinations were only briefly hosts. Others were much more familiar.

Cuba

Baseball was already quite popular in Cuba by the time teams decided to play their spring warm-ups there. The New York Giants were the first, setting up camp in Havana in 1937 as they prepared to successfully defend their National League crown. By the next year though, they moved on to Baton Rouge, La., and never returned for anything more than the occasional exhibition.

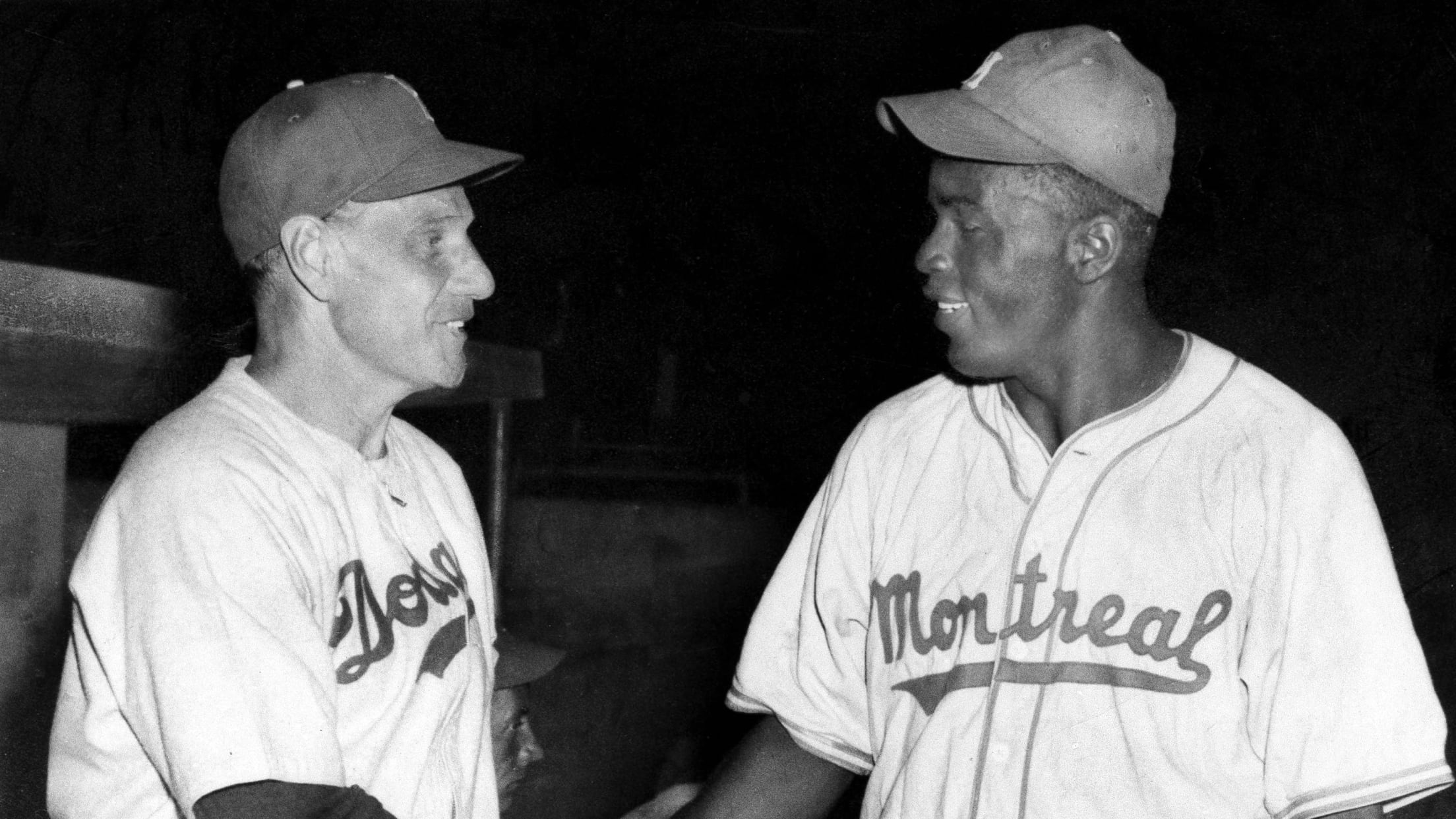

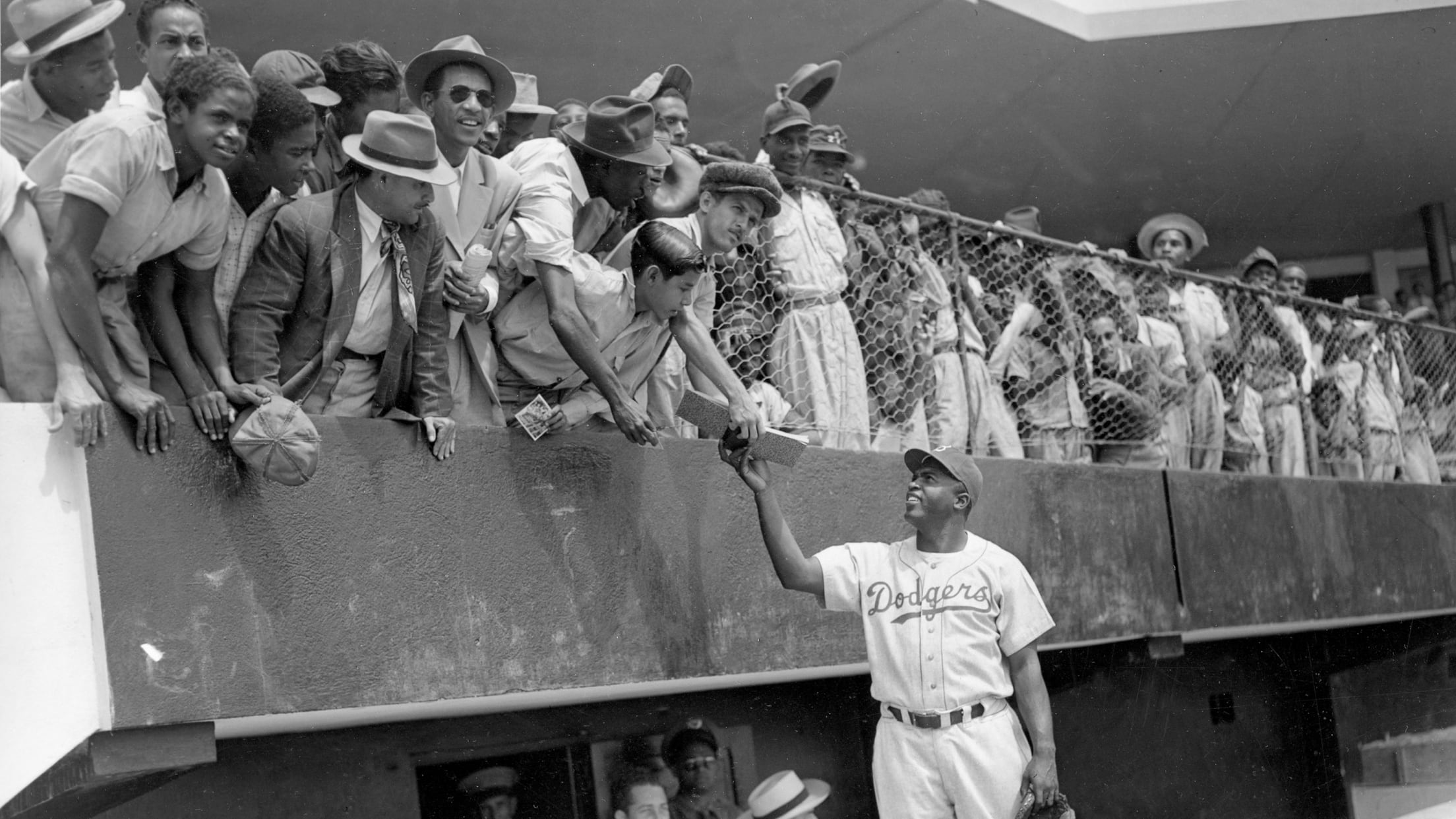

It was the Giants' crosstown rivals who became a more familiar presence in Cuba. The Brooklyn Dodgers set up shop at La Tropical Stadium in both 1941 and 1942 before travel restrictions kept them stateside for the next few years. When they returned in 1947, it was a historic occasion -- Jackie Robinson's first foray with the Major League club.

GM Branch Rickey intentionally chose Cuba for Robinson's first camp, as its baseball-crazed citizens were more accustomed to seeing African-American players. Robinson, Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella and Roy Partlow still had to stay in separate hotels from their white teammates, but Robinson won manager Leo Durocher over.

Durocher was so taken with Robinson that he wasted little time in squashing out a rumored petition signed by some of the white players who didn't want to play with him. He gathered the team in the kitchen of the Cuban hotel where everyone else was staying, and said, "This fellow is a great ballplayer. He's going to win pennants for us. He's going to put money in your pockets and mine. So, I don't want to see your petition, and I don't want to hear anything more about it."

Sure enough, Jackie made the team. The Dodgers went elsewhere for Spring Training in following seasons though, and a team would not return to Cuba until Rickey had moved on to the Pirates. A 1953 camp in Havana did not go well, and that was it.

Dominican Republic

One year after Jackie traveled to Havana for his first big league camp, he found himself in another Latin American country for his second: the Dominican Republic. After being promised $50,000 to relocate their camp, the Dodgers visited Santo Domingo, then known as Ciudad Trujillo for the Dominican president, Rafael Trujillo.

The New York Times raved about the Dodgers' accommodations:

"The [Dodgers] are headquartered in the Hotel Jaragua, which is slightly more impressive than the Taj Mahal. It gleams whitely in its setting among palm trees. A hundred yards beyond, the blue waters of the Caribbean curl against the beach. That's the kind of joint our Brooks have as their home. So far no one has complained."

The hotel might have been nice, but the Dodgers were not blown away enough to be tempted to return. Their longtime Spring Training facility in Vero Beach, Fla., was in the works and their Minor Leaguers were already using it. The Dodgers officially turned Vero Beach into "Dodgertown" in 1949 and didn't play anywhere else for the next 60 years.

Bermuda

Before the Yankees were a vaunted powerhouse, they were merely an unremarkable American League team called the Highlanders. They rarely competed for the pennant and were fully in the cellar after a 1912 season that saw them lose 102 games with an all-time low .321 winning percentage.

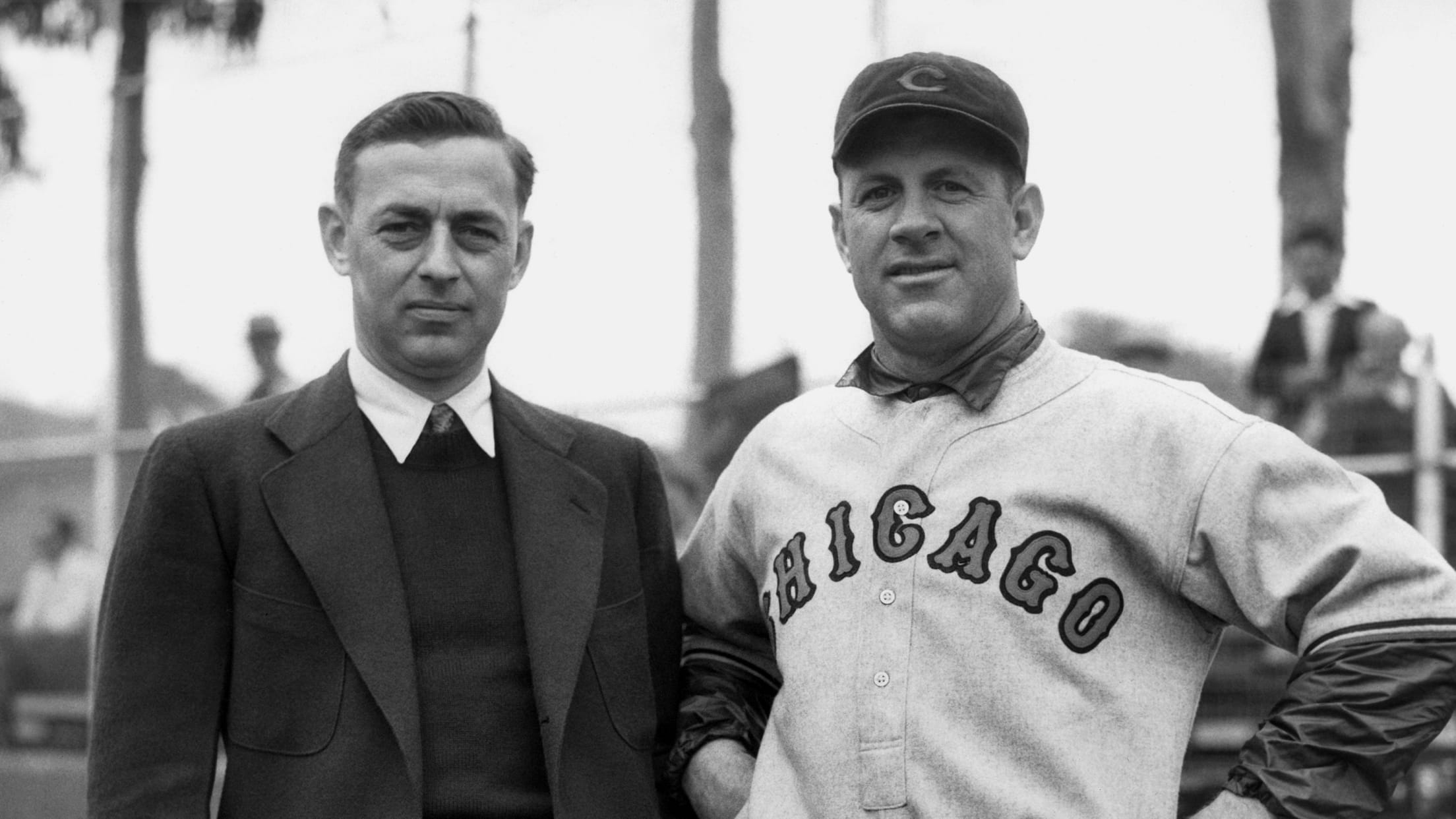

Seeking a change of pace, new manager Frank Chance (of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance fame with the Cubs) looked abroad. The team had been training in various locations around Georgia and Alabama for most of the previous decade, but Chance settled on Bermuda's Hamilton Cricket Grounds. (Yes, cricket.)

It was a strange setting, as the team often biked to the park to scrimmage against a Minor League team that traveled with them, the Newark Skeeters. Chance enjoyed the conditions and it seemed like a return trip to Bermuda would be in order for 1914.

Then, the team got seasick on the boat ride home and went 9-28 through the end of May. All such thoughts were quickly abandoned, as people quickly attributed part of the blame to the atypical Spring Training location. The team, which officially adopted the "Yankees" moniker that year, never returned.

Catalina Island

At first glance, it might not seem so strange that the Cubs used somewhere in California to prepare for the season, especially in the days before Major League Baseball was on the West Coast. The circumstances around their facility were what it made it remarkable. It wasn't just that the Cubs hosted Spring Training on Catalina Island -- they literally owned the island.

In 1919, owner William Wrigley, Jr. bought Catalina Island (located just south of Los Angeles) without ever seeing it. He had little idea of what to expect when he set sail for it, but he immediately fell in love. Within three years, he relocated the Cubs' Spring Training locale from Pasadena to Catalina Island, and it would be their home for the better part of 30 seasons, save for wartime restrictions. Wrigley had big plans in mind for the ballpark, which was constructed with Wrigley Field's dimensions in mind.

Along the third-base line, next to a row of eucalyptus trees planted for shade and protection from errant golf balls from the adjacent course, architects included a dedicated spectators’ entrance to grandstands projected to seat 1,000. Beyond the right-field fence, prescient planners drafted into their blueprints a series of bungalows or “casitas” designed for players and staff with families in tow. About 1,500 feet beyond the bungalows, directly down an extrapolated first-base line, Wrigley built a spring training bungalow for himself and his family on top of a 350-foot hill he dubbed Mount Ada in honor of his wife.

Wrigley made Catalina Island even more of an attraction by opening a 12-story dance hall and movie theater in 1929. It was a legacy that continued after his death in 1932, when control of the island passed down to his son, Philip Wrigley.

The younger Wrigley preserved his father's legacy on the island for several decades until deciding that it was time to move on in 1952. The Cubs relocated to Mesa, Ariz., though the Wrigley family maintained control of Catalina Island until 1975.

Mexico City

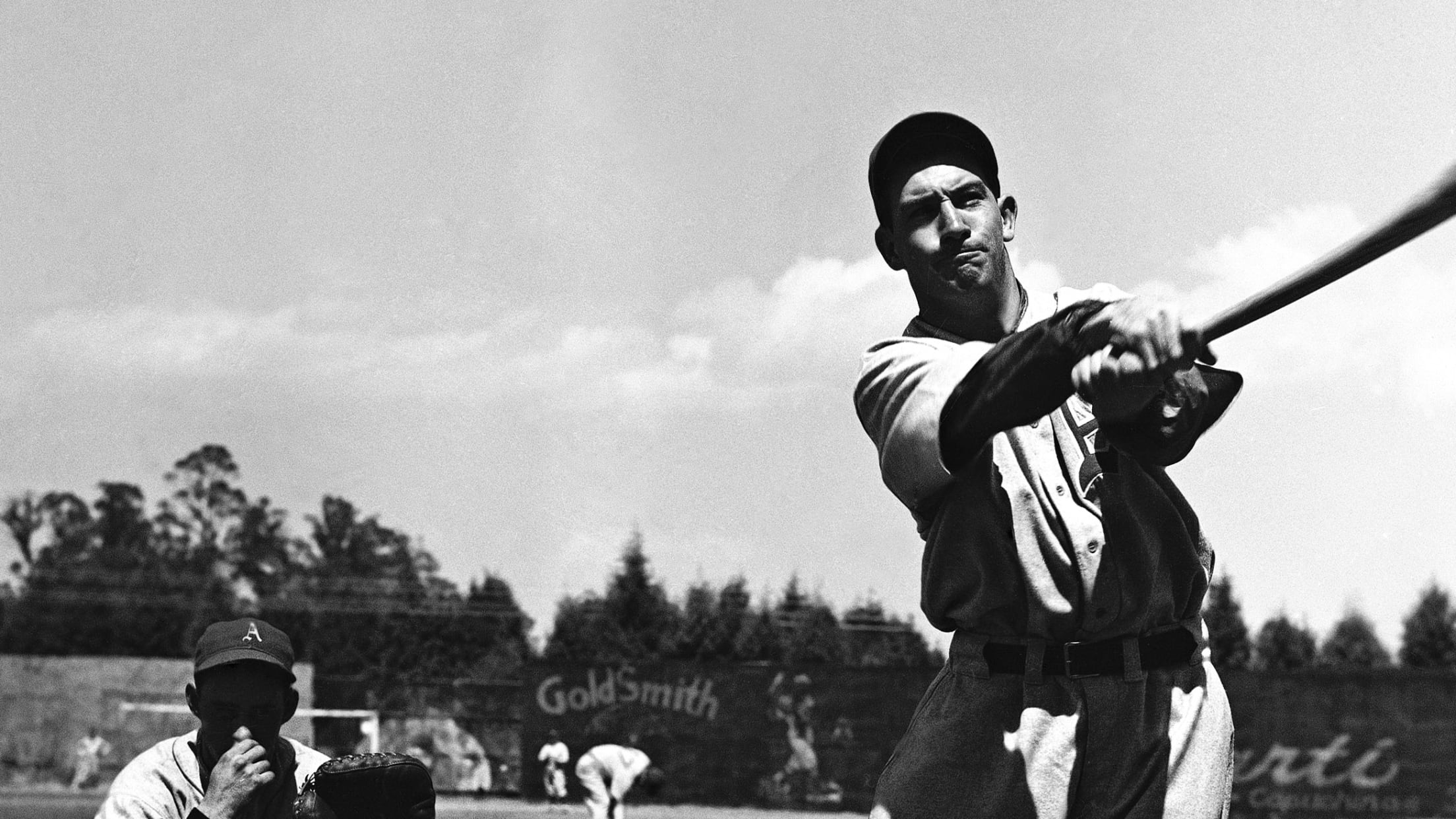

Two teams briefly set up camp in Mexico City to prepare for the season. The White Sox were first, arriving as the defending World Series Champions in 1907 and ready to play eight days of games against Mexican teams. Owner Charles Comiskey had ulterior motives, as he saw Latin America as the next hotbed of baseball talent. He hoped that the visit would help grow the game in Mexico and perhaps pay more dividends down the road.

Although the city greatly enjoyed baseball, the stint in Mexico City did not go well. Players complained about no hot water in their hotel rooms, and there was little telegraph connection with the United States. The prices for the exhibition games were also too high, and Comiskey suffered a loss on the endeavor.

Similar problems hit the Philadelphia Athletics when they journeyed to Mexico City for Spring Training in 1937. They had hoped for a spark after 12 seasons in Ft. Myers, Fla., but found no such luck. Flies and mosquitoes pestered Connie Mack's team and a nightclub near their hotel proved to be both too loud and too tempting. There were also a couple embarrassing injuries for reporters:

Two of the injuries suffered in Mexico City were by attending scribes as the Philadelphia Record's Red Smith spent a week in bed after watching an afternoon game bareheaded and Ivan Peterman of the Philadelphia Bulletin was confined to bed for three days after becoming infected from an insect bite.

The A's didn't return, but thankfully, baseball eventually found its niche in Mexico anyway.

Caribbean Tour

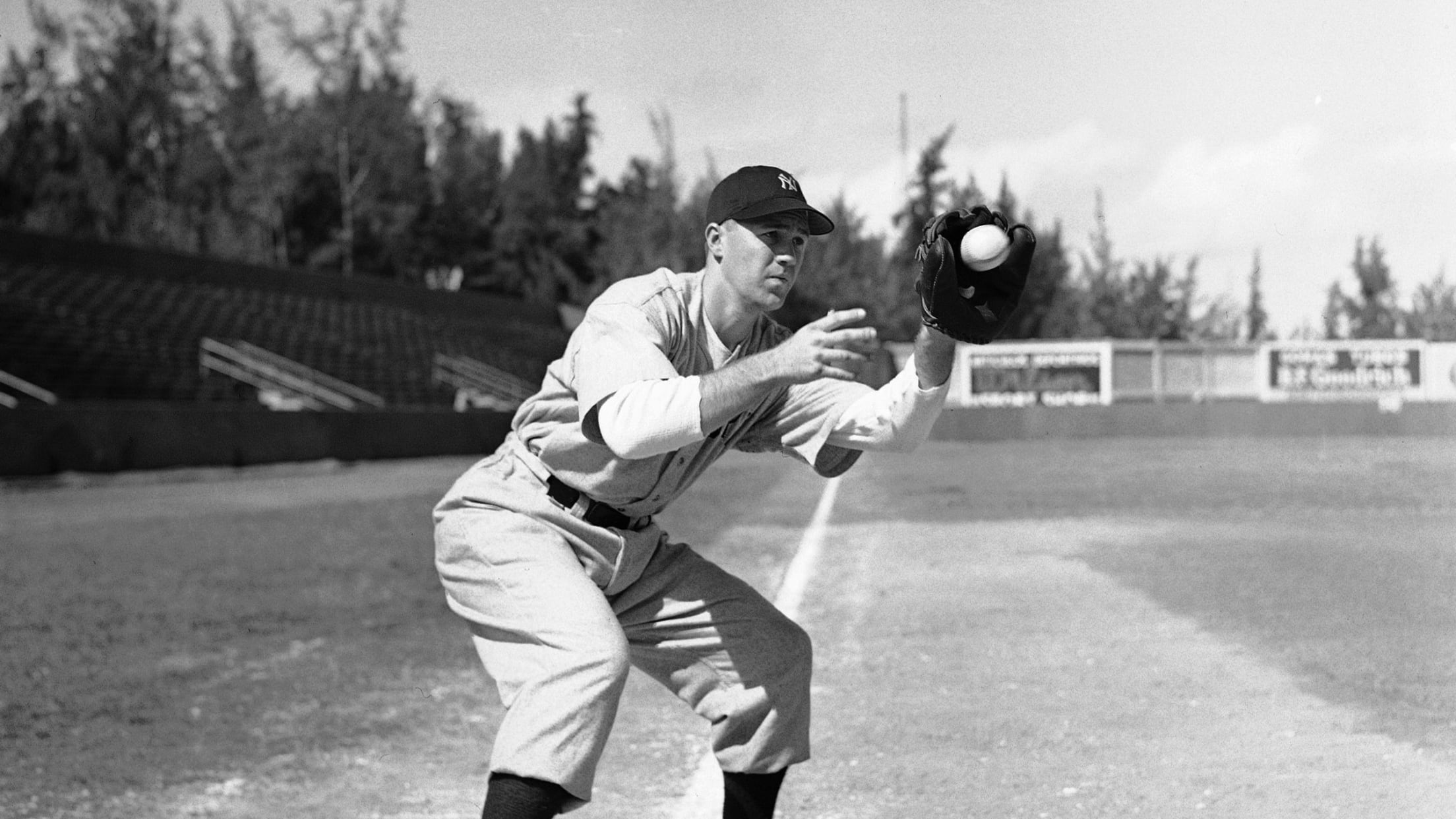

The Yankees turned their Spring Training in 1947 into a traveling show. They began in their normal locale of St. Petersburg, Fla., but quickly moved on to a visit around the Caribbean. Under new manager Bucky Harris, the Yankees played five games in Puerto Rico, six in Venezuela and three in Cuba.

The plan almost went south from the start, as a Puerto Rican rum distillery that was sponsoring the team provided too many samples to the eager players, leading one youngster to act far too reckless:

As the hours sped by and the drinks kept flowing, a debate started over the swimming and diving ability of a certain Yankee rookie. The fellow was built like Johnny Weissmuller in his prime and claimed to be as good a swimmer. Yankee veterans were not impressed and told the rookie to put up or shut up. ...

At midnight, the bettors and the star of the show assembled ... The bet was whether or not the "Yankee Weissmuller" could make the dive successfully from the third story balcony.

Immediately afterward, Harris had to get his team in order and the focus back on preparing for meaningful games.

The remainder of the tour went better. The Yankees’ Venezuela schedule included three contests with the Dodgers in Caracas before departing for Brooklyn's spring home in Cuba.

Controversy couldn’t quite escape them, though it was not the fault of the hosts. Dodgers skipper Durocher got himself in hot water for saying that commissioner Happy Chandler was unfairly targeting him for relations with gamblers, while ignoring Yankees president Larry MacPhail's vices. That led to a stunning season-long suspension that left the baseball world in shock.

Regardless of Durocher’s antics, the Yankees finished up their Caribbean tour with an 8-6 record. It turned out to be the beginning of another championship season.