Why exactly does Fenway Park have the Green Monster, anyway?

Over the years, the Green Monster has grown into one of the most beloved ballpark quirks in America. It's watched over some of the game's most iconic moments and caught some of its most iconic dingers. Celebrities want to sign it. Players want to know what's inside it. Fans are willing to travel from all over the country -- the world, even -- to see it in person. Which is why it's so ironic that the Monster was first built expressly to keep people out.

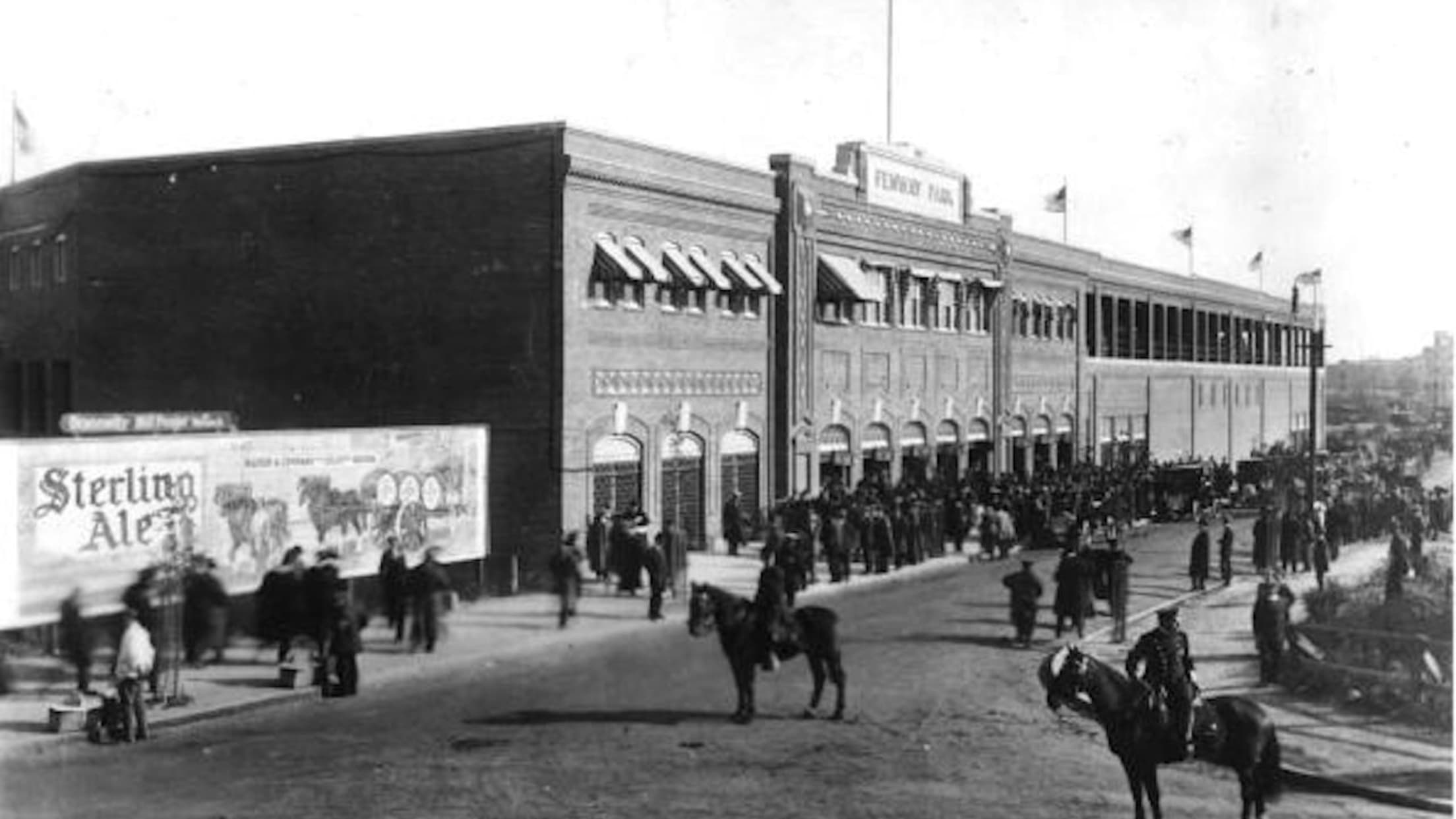

The story begins in the winter of 1910, when then-Red Sox owner and local businessman John I. Taylor decided his ballclub needed a change of scenery. The old Huntington Avenue Grounds had been the team's home since its inception in 1901, but it had seen better days -- there were patches of outfield where grass wouldn't grow and a shed just sort of hanging out in deep center. So, with just a year left on the lease, Taylor began to look elsewhere.

He landed on the corner of Lansdowne and Ipswich streets in Boston's Fenway neighborhood, a previously undeveloped bit of swampland that had been cleaned up significantly since the late 19th century. The area was ripe for growth, and architect James McLaughlin had drawn up some state-of-the-art plans for a steel and concrete marvel that, according to the Boston Globe, would "improve the grounds so that for capacity and character, the accommodations will be second to none in the country."

Taylor had land, a plan and plenty of money -- seemingly everything he needed. There was just one problem: He was worried about fans getting a free view from beyond the left-field wall.

Typically, outfield fences at the time were just a few feet high (remember, this was the Deadball Era, when even hitting a ball that approached the wall was a rarity). But Lansdowne Street just happened to house a few buildings that were fairly high, which -- at least in Taylor's mind -- would enable fans to catch a game from their window or rooftop.

So he had an idea: a 25-foot-high wooden fence, stretching all the way from beyond the left-field foul pole to the center-field flag pole, ensuring that the only people who would be able to watch Red Sox baseball were those who'd paid for a ticket. There was even a little embankment leading up to the wall, later dubbed Duffy's Cliff, that provided some extra seating for overflow crowds:

But it wasn't until 1933, when a fire destroyed much of the park, that the wall -- still just known as The Wall to locals -- would begin to resemble the Green Monster we know and love today. It was rebuilt in 1934 with a concrete base and a hand-operated scoreboard, both of which are still in use today. And 13 years later, the advertisements that had plastered the wall since its first game were removed, and it was painted the same shade of green as the rest of the ballpark -- hence the nickname.

The 1930s also brought another bit of Green Monster lore: a 23-foot-tall net above and beyond the top of the wall, installed in 1936 in order to keep home runs from damaging businesses on Lansdowne. In order to retrieve all those baseballs, team employees would scale a metal ladder to the top. The nets came down in 2003, when owner John Henry swapped them out for 269 seats showcasing one of the coolest views in sports. The ladder, however, remains very much in play, sometimes to hilarious effect: