Six seasons into the Statcast player tracking era, 2020 has brought us something new.

Gone is the previous camera/radar hardware combination that had fueled the system between 2015-19. In, as was noted in detail on the MLB Technology Blog in July, is an entirely new set of gear powered by Hawk-Eye, the camera system best known for fueling instant replay in professional tennis.

As was written at the time, "the Hawk-Eye Statcast system utilizes a total of 12 cameras around the park for full-field optical pitch, hit and player tracking. Five cameras operating at 100 frames per second are primarily dedicated to pitch tracking, while an additional seven cameras are focused on tracking players and batted balls at 50 frames per second."

That's compared to a single radar and two sets of three cameras apiece in the old system, and so far, so good. Now, what does this mean to you, the interested observer? At the lowest possible hanging fruit level, it means simply that more balls are being tracked. With the old radar/camera system, about 89% of batted balls were tracked; this year, through the end of August, that number is more like 99%. That's noticeable, right away.

But let's talk about something far more interesting than that. Let's talk about what's become known as pose tracking, a new phrase that's about to become extremely important.

With the old gear, players were, for lack of a better term, blobs. Their position was measured in terms of where their center of mass was, but that was about it. There was no indication of arms or legs, no real way to track explicit movements, arm motions or swing paths. That was fine, for what it was; it was, after all, the first time anyone had been able to track player movement at all in real time. It was incredibly useful to track starting depth, ending positions, different types of defensive shifts, running speed, strongest catcher throwing arms and so on.

But it was limiting, too, for all the reasons you could imagine. Did this first baseman do a better job of stretching for a throw than that one? No idea. Did a batter in a slump have a subtle change to his swing mechanics? We'd have loved to have known. Such are the limitations of blobs.

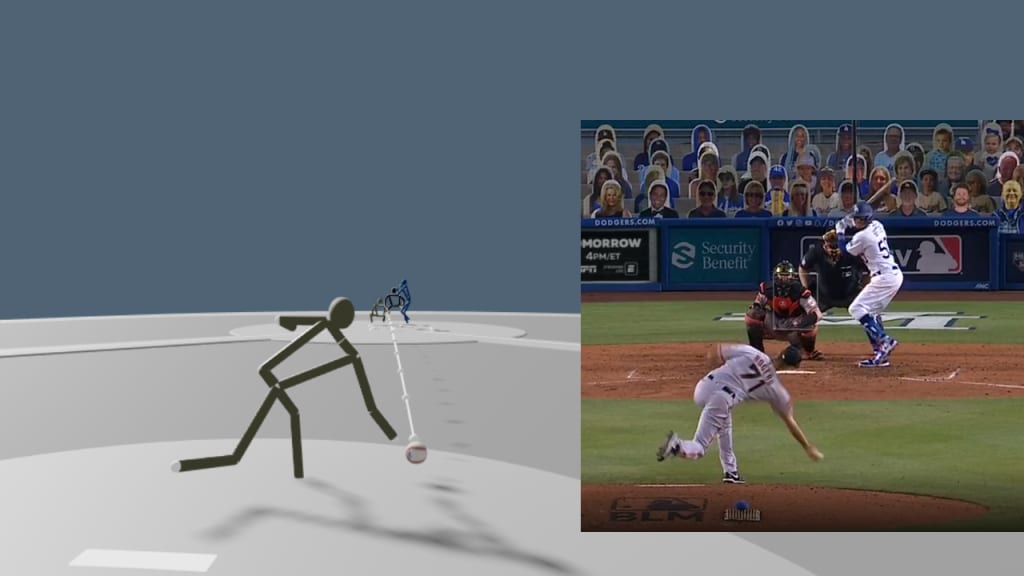

With pose tracking now an option, those kinds of questions -- and more -- are now potentially answerable. You can see what that means in the example picture below. See those green lines? They're arms, legs and everything else that makes a player look like a human -- and that opens all sorts of new doors.

Now that we've got a month-plus of data in all 30 parks -- that's the 29 normal North American ballparks and Buffalo's Sahlen Field, though of course Toronto's Rogers Centre will also be included once the Blue Jays are allowed to return there -- let's share some real-world examples, shall we?

Back on July 23, the Dodgers and Giants kicked off the West Coast portion of Opening Day in Los Angeles, with the Dodgers taking an 8-1 victory. Want to know what Giants submariner Tyler Rogers, owner of baseball's lowest release point, looks like? Here he is throwing a strike to Mookie Betts in the seventh inning.

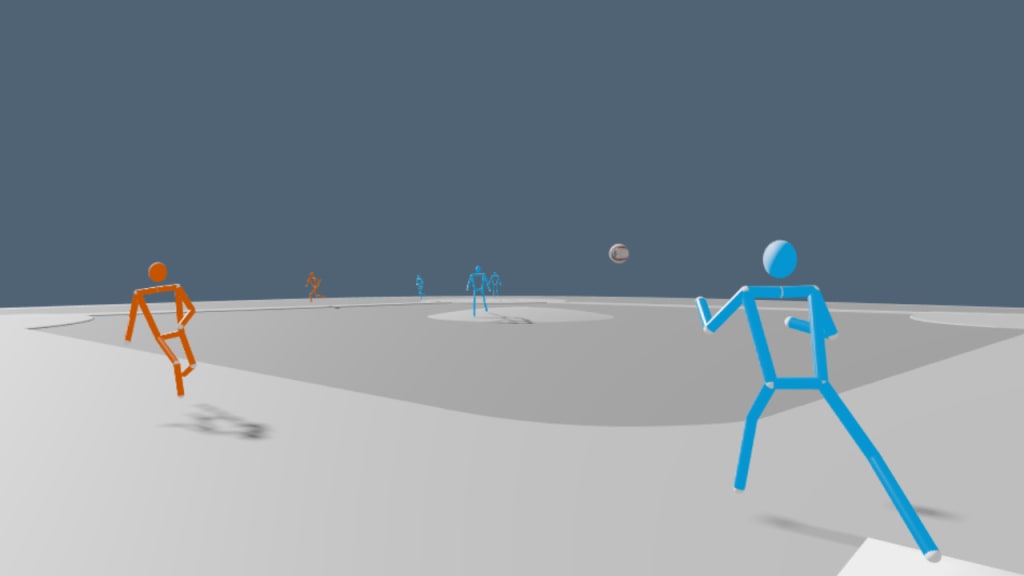

How does it feel to be second baseman Enrique Hernández trying to turn a 1-4-3 double play in the ninth as runner Alex Dickerson bears down on you? Perhaps a little like this.

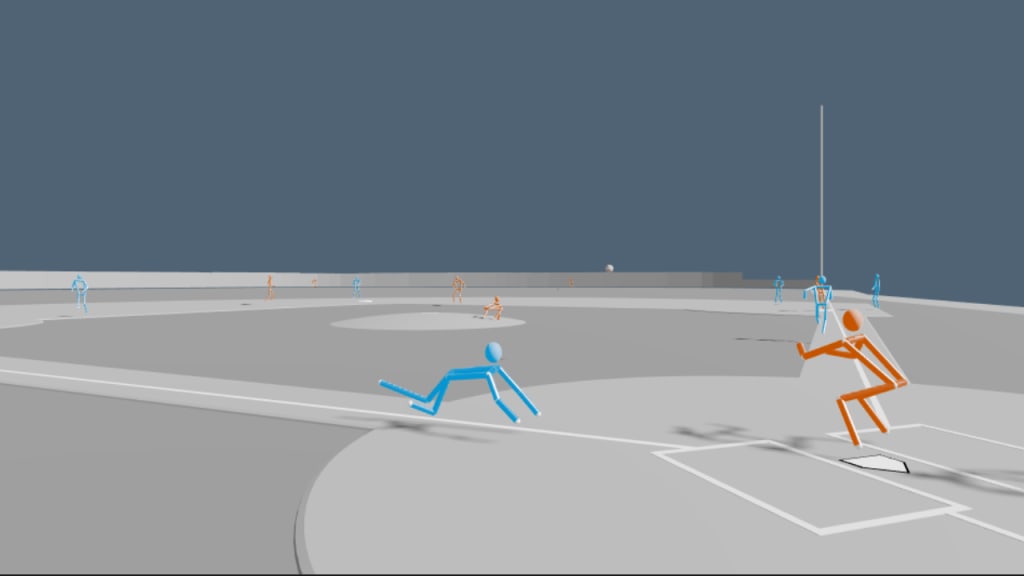

Did you like Betts sliding into home to score on a challenged 4-3 fielder's choice? We did, too -- and note the pitcher crouching on the mound to avoid being hit by Donovan Solano's throw.

The game was started for the Giants by Johnny Cueto, famous for his ever-changing pitching windups -- and his "shimmy." Last week, on the ESPN2 alternate Statcast version of "Sunday Night Baseball," we shared a collection of Cueto's deliveries from that July 23 game. He apparently enjoyed it so much that he shared it (with, we should add, his own selection of soundtrack) to 267,000 of his own Instagram followers.

So: What can be done with all of this? Each of the 30 teams are working on that right now, to be sure, but it's not hard to imagine where this leads.

From an entertainment perspective, the possibility of putting a "camera," virtual though it may be, literally anywhere on the field -- two feet in front of the catcher, perched atop the left-field pole, from the point of view of the shortstop and so on -- where traditional cameras can't go leads to endless possibilities.

From an analytical point of view, it's easy to see players and clubs being interested in knowing things like if a player hits the ball harder deep in the zone or in front of the plate, or if a struggling pitcher has changed his pitching motion in some way, or exactly how a shortstop's feet are moving while attempting to help him improve his reaction times.

Or, perhaps, things we haven't even considered yet. If we know baseball teams, they're always thinking about the next big thing. This might just be it.