"I made the Majors as a photographer. That was my only way into the ballpark," Steve Moore told me over the phone. "That's why I pursued it. I wanted to be a player -- everybody does."

Moore speaks quickly, as if the next idea is already sparking in his brain and he just needs his mouth to keep up. If you didn't know better, you'd think he was some fresh-faced kid just off the bus with an endless well of passion and enthusiasm. Instead, he's been doing this for over 40 years now.

"I didn't want to go to work and hate my job," Moore said. "I don't know what percentage of Americans go to work and hate their job, but it's a lot. I wanted to look forward to going to work and this did it for me. Then [I needed to] figure out how to get paid for it."

There may be only 780 active Major Leaguers at any given time -- a frighteningly low number for anyone trying to succeed on the ballfield. But the people with their faces pressed against viewfinders, for baseball photographers like Moore who spend their days down in the photo pits, the odds aren't much better. You've got to hustle. You've got to have a good eye. And as Moore makes quite clear, you've got to have a lot of luck.

He got his start as so many people do: He took the grunt work. He called up newspapers and took on small jobs, including shooting in the Minor Leagues. That eventually led to a few chances to snap some pictures from Yankee and Shea Stadium. From there, it was up to him to keep the pressure on, keep hustling. He called editors who barely cared to hear from him and he kept offering up photos until people took them. It was simply what a young photographer had to do to get noticed.

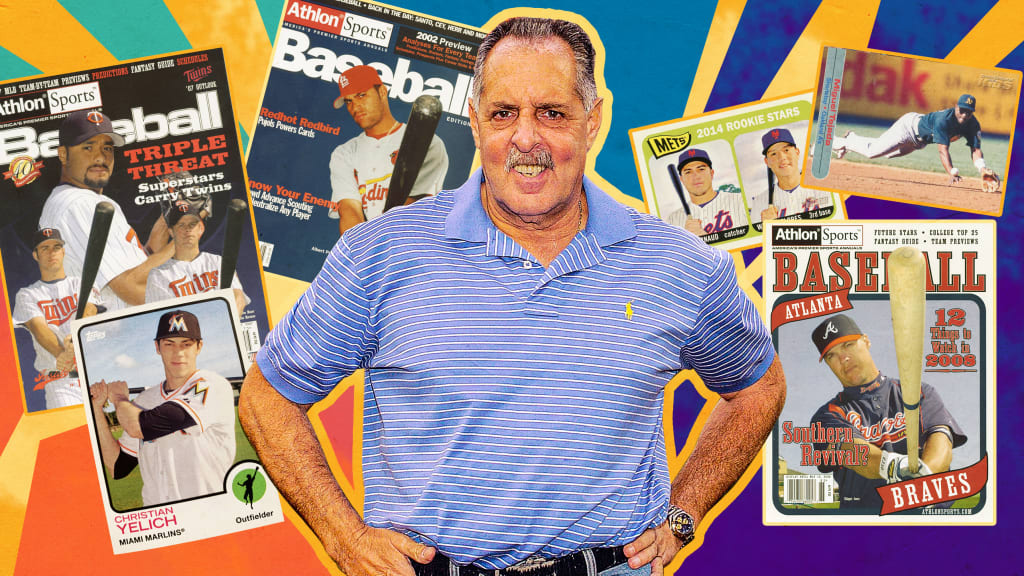

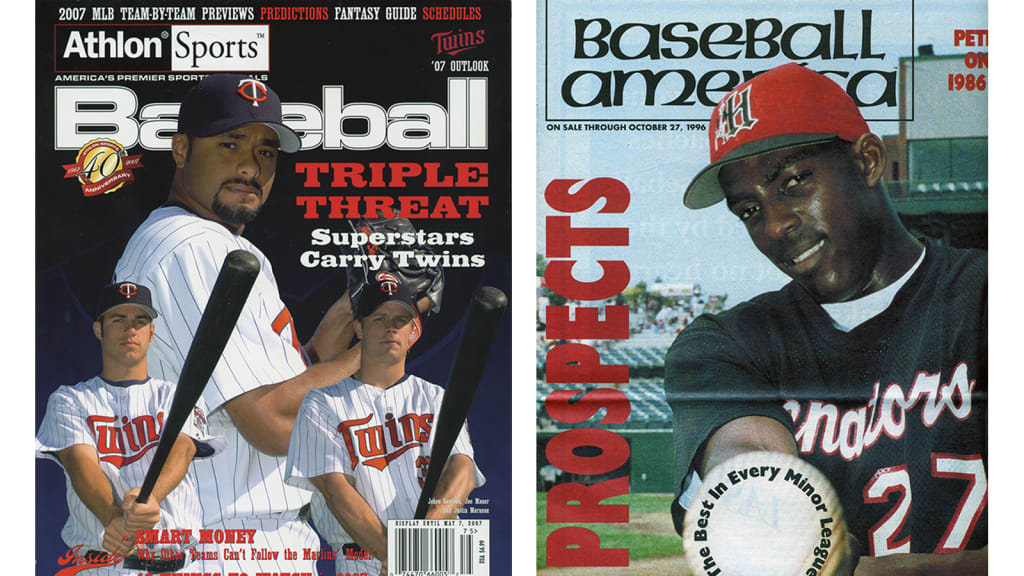

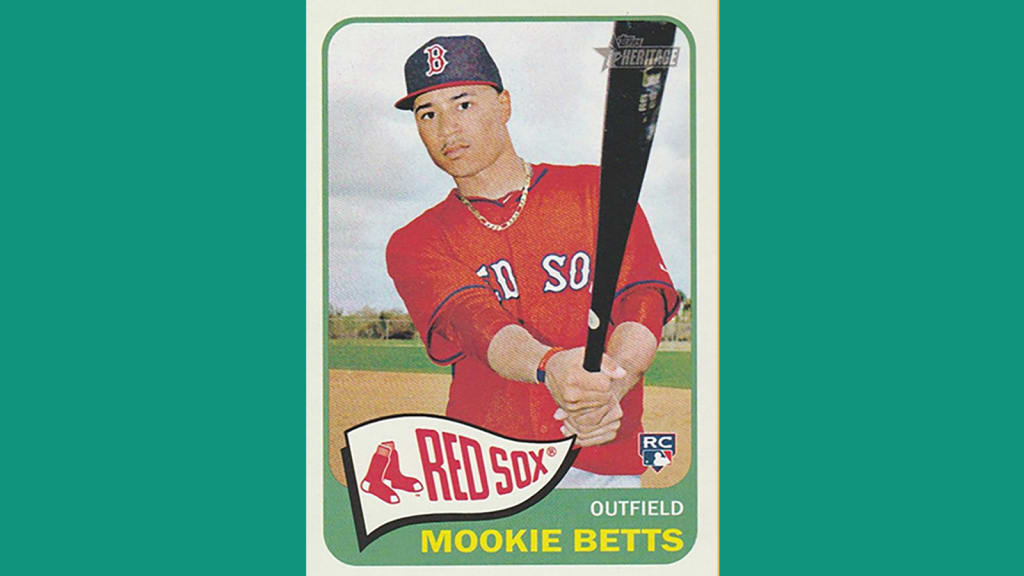

He would go to Spring Training with a notecard for every team filled with the 35-40 players on the roster he needed to photograph. They posed, bat in hand, uniform looking crisp and new. They were clean photos, ready to be sold and used for baseball cards, magazines and newspapers. He would be prepared when people came to him. He makes it clear that he's no one special, that plenty of other photographers work just as hard, take just as many good shots and did all the things he did to make their mark.

"The key to my success was when editors needed a particular player and nobody had it [among their regular photographers], they called me up," Moore said. "I said, 'Sure. I have it.' They do that three or four times, and you have it every time -- or they asked for 20 players and you got 18 of them the way they want and they're ready to go and they get them the next day -- you do that enough, they're gonna start calling you first."

He had to approach players, both scrubs and stars, and get their photo. Most of Moore's interactions were blasé, boring, simply a task that needed to get done. Sometimes they weren't.

Tony Gwynn used to bust Moore's "chops" for wearing last year's sneakers and agreed to get his portrait done ... once Moore proved on his little notecard that he had photographed everyone else on the Padres team.

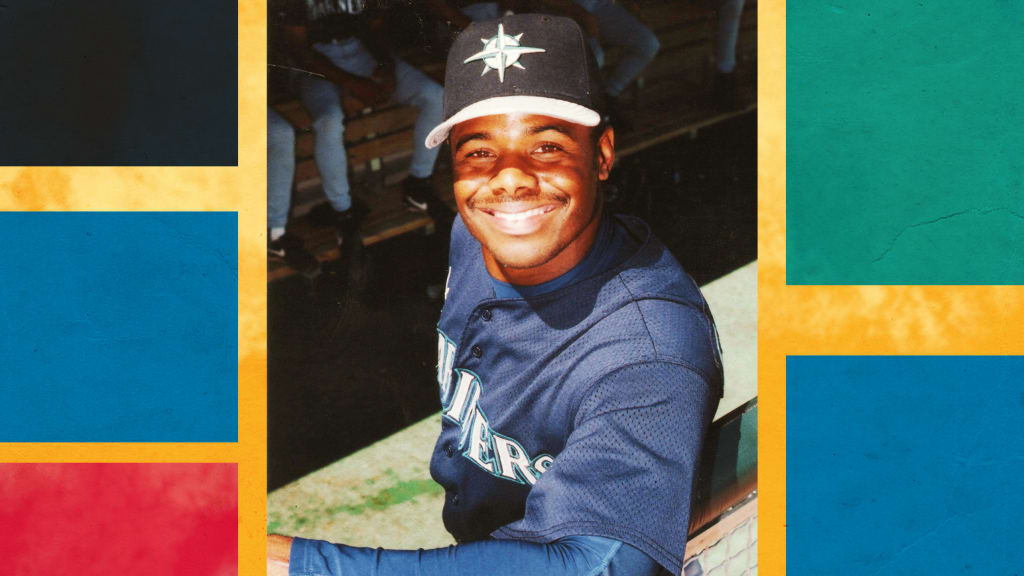

And then there was Ken Griffey, Jr. Junior was a superstar, who was constantly in the media spotlight, so he enjoyed giving Moore a hard time and playing games with him as he attempted to snap a sellable photo.

"He's a wiseguy," Moore said, fondly remembering the bouts of photographic cat and mouse they would play.

"He'd see me focusing in on him while he's in the dugout in the middle of the game, and he put his hat on backwards," Moore said. "He saw me, so I turn away, and I look out of the corner of my eye. He put his hat on frontward and I spin and shoot it and get it. It might not even be in focus, but he doesn't know that. And then he snapped his fingers like 'Damn, you got me on that one.' Next time I did it, he had his cap back on backwards. And he played games like that -- he knew I was trying to get pictures of him."

Looking for one specific photo, though, Moore asked Griffey directly. Moore told Junior that he would be in town for the next two weeks and would like to get a shot of Griffey leaning against the rail, smiling. Griffey agreed. So, five or six days later, Griffey came up to him.

"We can do those photos now," Griffey said. "If you'd like."

"I almost flipped out, like, 'Wow, he asked me?'" Moore remembered. "What he liked was that I asked for an appointment."

Of course, one other photographer standing nearby saw the opportunity to muscle in on the photo -- something that didn't bother Moore because he was a friend. But Griffey didn't like the imposition.

Griffey yelled at him, "This picture is for him only! He asked for this particular pose and he asked in advance."

Moore breaks down laughing as he shares the story. He had to tell the other photographer that it was OK, that Griffey wasn't really going to shove the camera down his throat.

Moore's photographs -- many of which are now cataloged and archived on his site, Steve Moore Archives -- have graced magazine covers, photo spreads, and countless baseball cards. While the covers are nice and the spreads will even give credit, there was always a special thrill when Moore's photos were used on those little pieces of cardboard.

"I used to go to baseball card stores when the new cards came out and flip through boxes of them," Moore said. "And I'd go, 'That's mine!'" after noticing the subtle differences that marked these as his photos.

"Of course, back then, common baseball cards were like a nickel," Moore joked. "I'd pick out whatever I had and they'd make a big sale of like $4, and I'd go home with the cards that I shot."

(For those curious, while card companies will sometimes mail boxes of product to their photographers, that's not usually the case.)

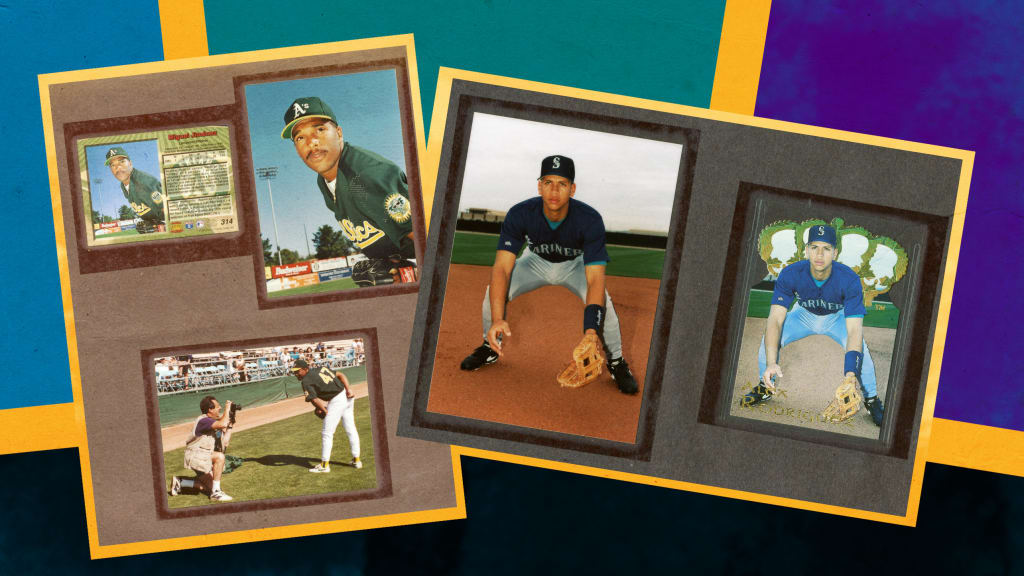

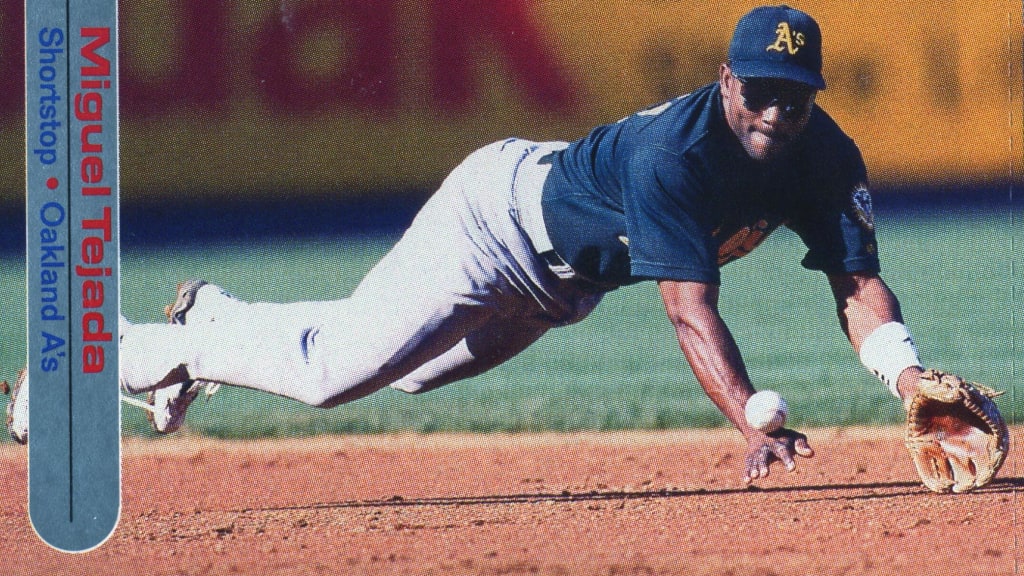

His favorite card, the one that stands out most in his memory, is one that had to be carefully torn out of a sheet. Moore tells it like it happened just yesterday, like the entire day has been captured perfectly in his memory.

"I was at Yankee Stadium one day," Moore said. "And Yankee Stadium on a beautiful day in August, around 10 minutes to four to 20 minutes after four -- it's the most gorgeous light in the world. You could have your cameras set on anything and the picture would be beautiful just because of the light. It's right before the sun goes behind the stadium. When it's halfway behind, you get that black background with the sun, like a spotlight on whoever you're shooting.

"So, the Oakland A's are playing the Yankees during that time, a beautiful day. And I go into the first-base photo pit. We normally shoot batters and stuff. I decided to shoot the shortstop, [Miguel Tejada], who was having the best season of his career. The first or second pitch was a ball hit up the middle and he dove. I was still using film at the time, it wasn't even digital. He dove, and I nailed it."

Tejada didn't actually make the play -- the ball rolled under his glove and into the outfield -- but that's not what matters. What matters is that this was the MVP that season, a superstar captured in action. Plus, it doesn't hurt that it looks like he's making the play.

It first ran as a "double truck" or double-page spread in Sports Illustrated -- a big deal because SI had their own photographers on staff.

"If you have something spectacular, they'll pay for it," Moore said about SI. "If it's generic, they won't even look at it."

It was then used as a card in the quintessential '90s magazine, SI for Kids. While Moore has plenty of his cards -- though not all that he's shot -- this was one Moore wanted to keep and give out to his family members. It was a photo that displayed a lifetime of hard work and he wanted to share.

Moore has a tell that he watches for when trying to get one of those perfect pictures.

"If you're shooting the plate and a guy hits a liner to third base, there's no chance that you could pivot and get that," Moore explained. "But if you're on the third baseman, and you see his eyes start to bulge out of his sockets, you start shooting and make sure you're on him. A lot of times if you're a split-second slow, you try to get on him and you get the left-field fence with autofocus.

"You blow it too, and don't let any photographer tell you that he never blew one," Moore adds. "It happens all the time. Sometimes you get lucky."

That's all par for the course in the job Moore has loved for over 40 years. He may not be a household name, but if you've bought baseball magazines or opened up a pack of cards, you've likely seen the game through his eyes, through his lens.

Maybe Todd Zeile summed it all up best. Zeile played for 11 different teams in his big league career, and every time he wound up in a new jersey, Moore had to get the new photo. So, after another trade and another photo session, Moore approached him.

"When we were done, I asked him, 'You don't seem to like getting photographed. Why are you so cooperative?' He just looked at me and said, 'It's part of the game.' I like that answer."

---

Photos by Steve Moore / Steve Moore Archives. Design by Tom Forget.