Across the world, millions of people continue to work remotely while practicing social distancing. Routine social interactions that we may have once taken for granted, like making small-talk with a colleague or meeting an old friend for lunch, are now sorely missed.

During this unprecedented period of prolonged isolation, Orioles players past and present, who share the timeless bond of having played in professional baseball, have found ways to stay connected with one another.

Dick Hall was born September 27, 1930, in St. Louis, Mo. A right-handed pitcher and outfielder, he spent nine seasons with the Orioles, and is a two-time World Series champion. While with the O’s, Hall was known for his pinpoint command; he issued just 80 non-intentional walks in 770 innings for a 1.005 WHIP, and was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame in 1989.

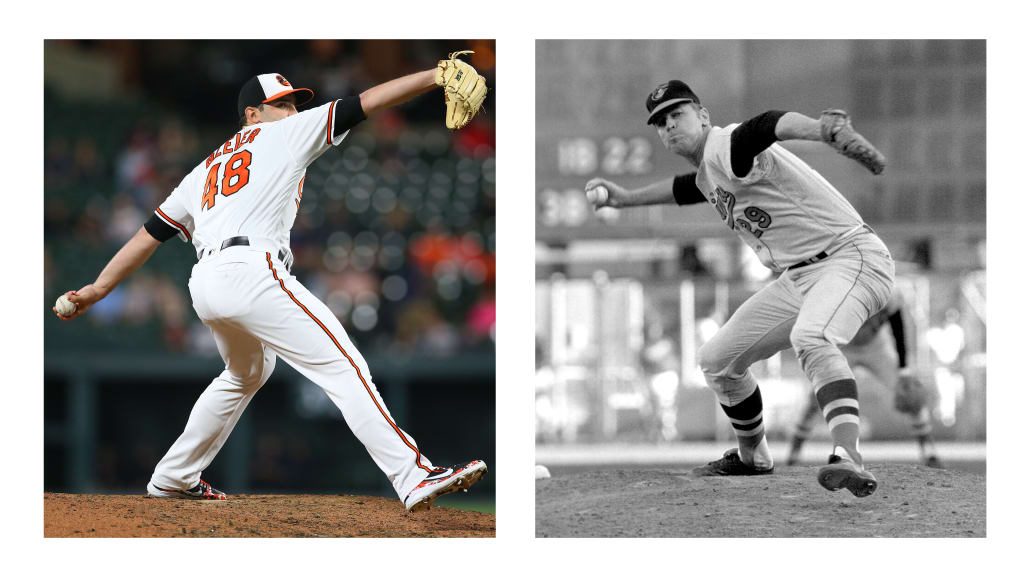

Last month, Orioles reliever Richard Bleier called to check in on Hall, who has lived in the Baltimore area since his playing days.

“I can talk baseball for 90 hours,” Hall jokingly warned at the beginning of the call. “So if I talk too long, let me know.”

The conversation began with the two pitchers discussing their current whereabouts. Bleier joined the call from the backyard of his West Palm Beach, Fla. home, while Hall was in Timonium. Although there were more than 1,000 miles and 56 years between them, they had more in common than they realized.

The two shared a mutual friend in Orioles Legend and Hall of Famer Jim Palmer. While Bleier only knows Palmer the broadcaster, Hall once carpooled with “Cakes" and Dave McNally from their homes in the Baltimore suburbs to Memorial Stadium.

Both men are fathers, with Bleier and his wife, Brett, having welcomed their first child, daughter Murphy, into the world in January. Hall, now 89 years old, is a great-grandfather, with several of his great-grandchildren living in the region.

The two Orioles spoke for nearly an hour, with Hall reminiscing about 30-hour train rides from Chicago to Boston and pitching at Memorial Stadium. He even recalled the night he spent at Branch Rickey’s house before signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1951.

When Richard Bleier made his Major League debut in 2016, he was playing the same game that Hall once did, but it had changed dramatically. Gone were the days of trains shuttling players from city to city. And travel wasn’t the only part of the game that had evolved.

“When I started back then, you really didn’t get any coaching,” Hall explained. “I never saw a video of myself or the opponent. They didn’t have such things.”

Even without the analytics and specialized coaching of today’s game, Hall put together an impressive career, going 93-75 with a 3.32 ERA and 71 saves in 495 games (74 starts).

A few days earlier, catcher Austin Wynns had connected with Orioles Hall of Famer Eddie Watt.

"My experience on the phone with Eddie was amazing,” shared Wynns. “It's not every day you speak with a man of his era. He is an encyclopedia of knowledge of the game of baseball and it was an honor to have a conversation with him."

Much of Watt’s knowledge came from the eight seasons he spent in Baltimore, from 1966 to 1973. During that time, he made 363 appearances for the Orioles, going 37-34 with a 2.74 ERA, the third-lowest career ERA of any pitcher in Orioles history. He was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame in 2000.

While speaking with Wynns, who is one of three young catchers on the Orioles 40-man roster, Watt emphasized the importance of the relationship between the pitcher and the catcher, calling it “the most important relationship on the field.”

Having last played for the Orioles nearly 50 years ago, Watt also stressed never taking anything for granted, and “appreciating every moment in this game.” Wynns, who turned 29 in December, soaked up every piece of knowledge he could from the 79-year-old veteran.

Wynns wasn’t the only Orioles catcher checking in on a player from the past during this unplanned hiatus from baseball. Earlier this month, 25-year-old Chance Sisco reached out to 81-year-old Vic Roznovsky, who appeared in 86 games for the Orioles between 1966 and 1967, primarily as a catcher.

Roznovsky, who lives in Fresno, Calif., a couple hundred miles north of where Sisco was born, recalled his playing days with the Cubs, Orioles, and Phillies, including being a member of the 1966 World Series champion Orioles team.

“You got traded over there and you win a World Series in your first year [with the Orioles],” said Sisco. “How about that?”

“That wasn’t too bad,” Roznovsky joked. “I was there a couple more years. I got the ring, and it was great for me.”

In addition to playing the same position for the same team, albeit many years apart, both Sisco and Roznovsky throw right-handed and bat left-handed, a rare combination for a catcher in the Major Leagues. Roznovsky, who was known for having a rocket of an arm behind the plate, even coached Sisco on throwing out would-be base-stealers.

“The thing you have to do as a catcher is have the same throw all the time behind your ear,” he explained. “You don’t want the ball moving; you want it to go straight.”

While much of the conversation focused on the past, towards the end, Roznovsky set his sights on the future.

“Do you think you’re going to have a good year for yourself?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” Sisco replied without hesitation. “I’m confident in this season. Obviously, we’re not playing right now, but we’re trying to get back there as soon as possible. We need baseball back.”

When the two catchers spoke about the possibility of the Orioles travelling to Anaheim this season, Roznovsky already had a plan to meet Sisco in person.

“Get me a good seat, me and my wife,” he said. “You can get me dinner after the game. I’ll buy the beer, and you get the food. Okay?”

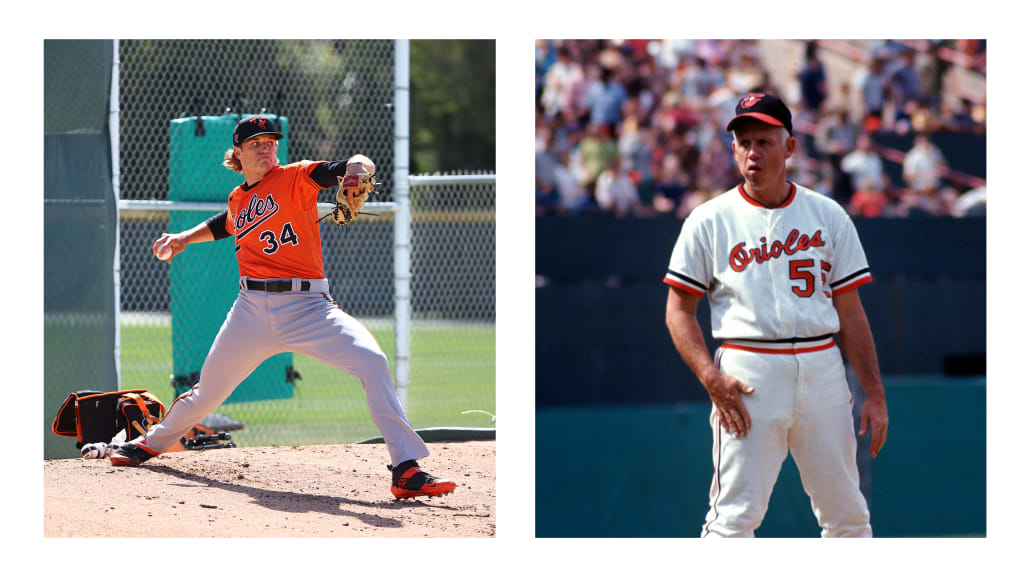

Meanwhile, minor leaguer Isaac Mattson and Orioles Hall of Famer Billy Hunter were making their own plans for an in-person meeting once the baseball season finally gets underway.

Mattson, a reliever, and Hunter, who wore many hats throughout his near 50-year baseball career – including as a shortstop, coach, manager, and athletic director – are both from small western Pennsylvania towns. The two caught up with one another on the phone last week.

A member of the Towson University Athletics Hall of Fame, Hunter originally signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1948, and was at one point considered the heir apparent to Pee Wee Reese before being traded to the St. Louis Browns in 1952. After one season in St. Louis, the team — along with Hunter — moved to Baltimore. He would go on to make the start at shortstop on Opening Day 1954, the club’s inaugural season in Charm City.

Following his playing career, Hunter spent 13 years as the Orioles third base coach before managing the Texas Rangers for two seasons. He then became the head baseball coach at Towson State University before being named athletic director there in 1984. In 1996, he was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame.

Mattson, who was originally drafted by the Los Angeles Angels in 2017, was traded to Baltimore last offseason along with Kyle Bradish, Kyle Brnovich, and Zach Peek in exchange for Dylan Bundy.

“You’re going to get a shot at the big league club this year, right?” the 91-year-old veteran asked.

“Hopefully. That’s the plan,” Mattson replied. “I’m training and trying to stay as motivated as possible given the circumstances.”

Part of Mattson’s training, he explained to Hunter, involved building a pitcher’s mound in the backyard with his father so that he could continue to throw and be prepared when the season does begin.

“If you’re with the big [league] club, you can count on me coming to say hello to you personally,” Hunter told Mattson. “I’m wishing you really good luck, and looking forward to meeting you [in person].”

That same sentiment echoed at the end of each call between the current players and Orioles Alumni. No matter where they were in the country at the time, they made a meaningful connection with each other, one that they hoped to continue. Now more than ever, it is crucial to stay connected, and to look out for those who may be feeling isolated. Because of technology, the distance between two people is no longer an obstacle to friendship, and these players proved that age isn’t, either. When baseball does return, there will likely be a few more former players in the stands at Camden Yards, cheering on the next generation of Orioles.