For Monday’s Game 3 of the World Series, it’s difficult to imagine a larger difference in the resumes of the starting pitchers. Texas has living legend Max Scherzer, a three-time Cy Young winner with a likely place in Cooperstown, who all but single-handedly willed his Nationals team to the 2019 title. Arizona counters with Brandon Pfaadt, a rookie who posted a 5.72 ERA this year -- when he wasn’t serving one of his three stints with Triple-A Reno.

On paper, it’s got to be one of the largest mismatches in recent World Series history. But the games, as they say, aren’t played on paper. Scherzer missed the American League Division Series with injury, and he was hardly his usual dominant self in the AL Championship Series. And Pfaadt? After a just-OK outing against Milwaukee in the National League Wild Card Series, he held the Dodgers and Phillies to a mere two runs over three starts.

That 5.72 ERA sure is ugly, but it also doesn’t really matter at all any longer. In the same way that Kevin Ginkel remade himself this season from unremarkable middle reliever to dominant postseason arm, all that matters is the type of pitcher Pfaadt is right now -- and he’s considerably different than he used to be.

"I think the hardest moment was definitely getting sent down -- that's going to be hard for everybody," Pfaadt said on Sunday. "But I think it all depends on the way you take it, which road you want to take. And I chose the road to the positive mindset and go down and work on things, get better and here we are. It all paid off."

Welcome to the new Brandon Pfaadt

It’s not like Pfaadt has no track record, of course. He led the Minor Leagues in strikeouts last season with 218, and in May, MLB Pipeline rated him as the No. 33 prospect in the game.

But Pfaadt didn’t make Arizona’s Opening Day roster, edged out by Ryne Nelson and -- remember him? -- Madison Bumgarner in the starting rotation. A month into the season, he was tapped to make his debut against the same Rangers he’ll see in Game 3, and it did not go well, as he allowed seven runs on nine hits (including four homers -- Josh Jung got him twice, while Jonah Heim and Leody Taveras did so once apiece) in 4 2/3 innings.

In 23 2/3 innings over five starts, he allowed 22 runs, and Arizona sent him back to Triple-A for most of June. He came back up for one more uninspiring start on June 29, allowing six runs in two innings against Tampa Bay, and back to Triple-A it was. When he came back up for good on July 22, Pfaadt’s ERA stood at 9.82. Batters had hit .346/.402/.700 (1.102 OPS) against him. But the team hadn’t lost faith, either.

“Going up and down,” said Pfaadt during the NLCS, referring to his trips to Triple-A this season, “they said that I would pitch in meaningful games going forward at the end of the season, and that's where we are right now.”

Pfaadt got into 13 regular-season games from that point on, and while a 4.22 ERA isn’t exactly spectacular, it’s considerably better than the 9.82 he’d posted before. While homers remained a problem, the .299 OBP he allowed in that final stretch was massively better than the .402 he’d allowed before. It was actually good, similar to what established arms like Framber Valdez and Kevin Gausman allowed over the same timeframe.

That didn’t happen by accident, of course.

“Every time he came back to the big leagues, it was like, ‘OK, he learned something else when he was down there,’” said teammate Zac Gallen.

Maybe we can learn too. Let’s see if we can find what turned Pfaadt from an up-and-down arm spending half his time with Reno to a starter the D-backs are absolutely counting on in the World Series.

The big change

On July 26, after Pfaadt had made his first start in the big leagues in nearly a month, MLB.com’s Steve Gilbert presciently wrote a newsletter titled “How the D-backs changed Pfaadt's approach before callup.”

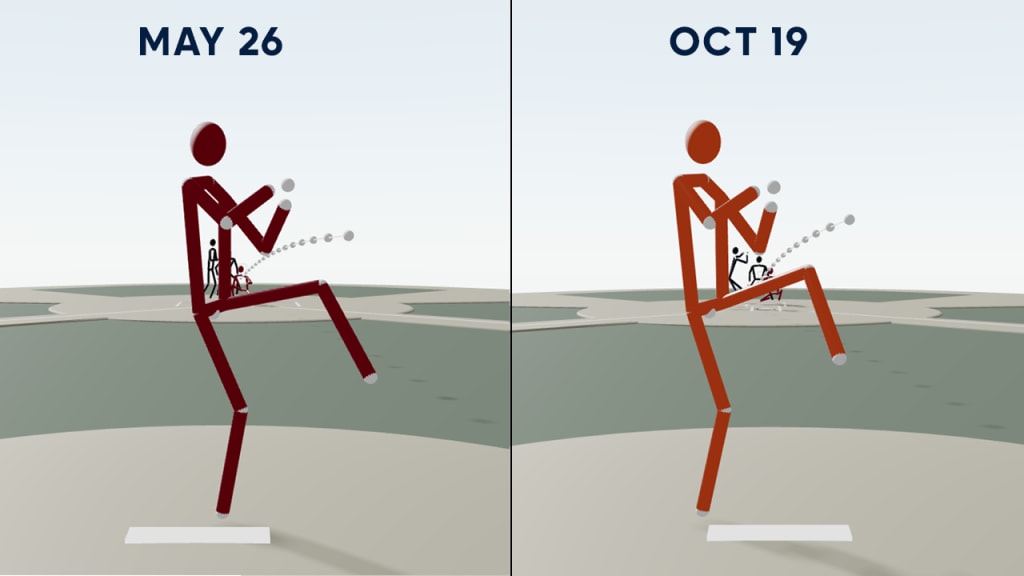

Within, Gilbert described how second-year D-backs pitching coach Brent Strom -- legendary in the game for his eight seasons leading the data-driven Astros pitching staff from 2014-21 -- came to the conclusion that Pfaadt ought to move his position on the mound from the third-base side to the first-base side, a change that is extremely easy to see, especially if we bypass inconsistent camera angles and just get right to the Statcast tracking data, picking random games before and after the change.

Look at the legs and the rubber. It's a huge change.

“Before, he was throwing balls out of his hand which became strikes,” Strom said in July. “Now we have pitches that are strikes that can become balls, which is what I was trying to achieve.”

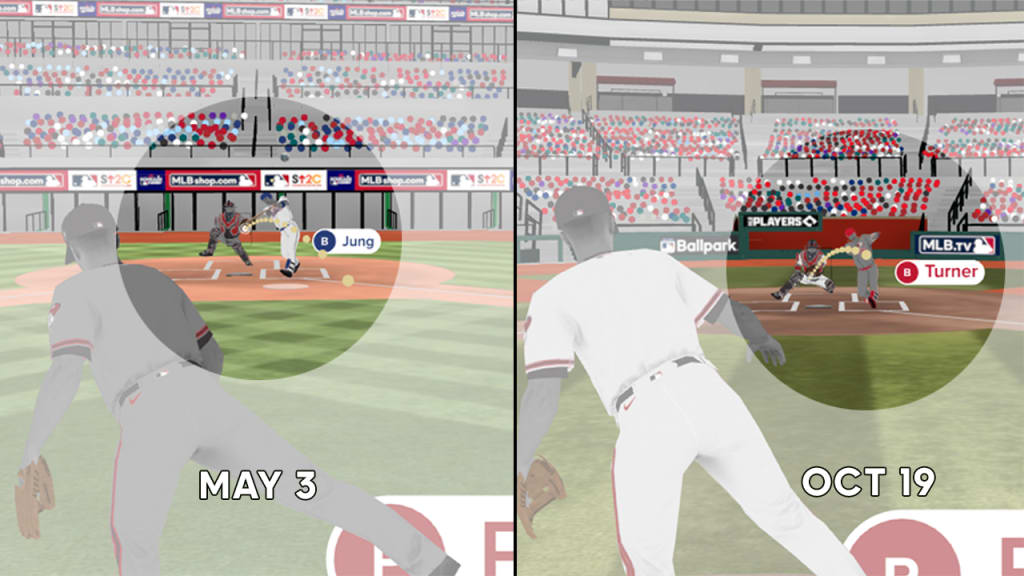

To really illustrate this, let’s cherry-pick at a pair of sweepers Pfaadt threw to right-handed batters, one to Jung in his debut, then another to Trea Turner during the NLCS.

From Pfaadt's old third-base side release point, the sweeper starts as a ball, as Strom said, and curves right into Jung’s bat path -- and 427 feet later, it was a home run. Against Turner, it started out looking more like a strike before moving outside, and Turner swung through it for a first-pitch strike. (Click here for a larger version.)

“There were some adjustments made both times I went down,” Pfaadt said during the NLDS, “and coming back up, the results got better and better every time. One big adjustment was moving to the first-base side of the rubber, just kind of helping those pitches tunnel better.”

During the playoffs, Pfaadt relayed the entertaining details of how Strom had pitched the idea of moving on the mound, even though it had been weeks since he’d been demoted to Triple-A. It started with a mid-July phone call, late at night.

“It might have been 11 p.m.," Pfaadt said. "I was like, ‘What does he want?’ It was moving to the first-base side of the rubber. And he had a whole diagram of every single pitch on every side of the plate. I was in Kentucky for All-Star break. I flew home. I was sitting in my parents' house and [got] a call from Strommy. 'Let's see what he wants.' It was funny.”

So if Pfaadt now looks different than Pfaadt then, it’s because he’s literally standing in a different place. What else?

Now he’s got a sinker

If Pfaadt believes his sweeper and sinker tunnel better now to righty hitters, one important thing is that now he’s got a sinker at all -- which he didn’t in his first stint in the Majors. Pfaadt made those five starts in May, and his sinker percentage was 0%. We can dig into Triple-A pitch data, too. Pfaadt made five April starts for Reno without a sinker, then three more in June without one, and then it showed up as a new pitch for his June 18 start in Las Vegas.

It’s become a decent enough pitch that he’s thrown it 19% of the time in the postseason, but it’s primarily become a weapon against lefty batters -- against the Phillies in Game 7, 37% of his pitches to lefties were sinkers.

Just look at how he attacked Kyle Schwarber, throwing him four pitch types in five pitches, including getting the strikeout on the sinker that he didn’t have before. That came in low while the four-seamer came in high; it came in low while the sweeper did as well. The sinker is something of a bridge between the two pitches.

“I think the sinker helps the four-seam and the four-seam helps the sinker,” said Pfaadt. “Just mixing them and knowing when to use them and keeping them off balance with two fastballs is huge, not for only those pitches but also the offspeed to come into play, too.”

It’s not in and of itself a great pitch -- in September and October, it’s been essentially average, by outcomes and run values -- but it gives batters another thing to think about.

Between the change on the mound and the new sinker, Pfaadt has massively helped his sweeper, which you might consider his only true “plus” pitch.

Pfaadt's use of sweeper

- First 6 starts: .250/.294/.594 (-1 run value)

- Since last recall: .174/.226/.240 (+10 run value)

So now we know that Pfaadt has added a new average pitch (the sinker) and he’s made his best pitch better (sweeper). He also, apparently, eliminated a glove tap that batters may have been able to pick up upon; watch how against Texas in his debut, his hands separated from his glove at the end of his windup, while against the Phillies last week, the hand stayed securely in the glove.

There’s one last key here: the four-seamer, or lack of it.

All of which means his four-seamer gets lit up less

This was the real problem in Pfaadt's first shot at the Majors, that his primary four-seam fastball is … just OK, or maybe not even. At 93.7 mph, it doesn’t have terribly notable velocity. There’s not any particularly interesting movement to it. It’s a straight fastball that’s not thrown hard enough to do any damage.

But in May, without the sinker, without the angle on his sweeper, without the faith in his changeup, Pfaadt threw the four-seamer a lot, nearly six out of every 10 pitches (56%) in his first month in the Majors, which is too much for a pitch that isn’t really effective. Plus, unlike some of his other pitches, it hasn’t even really improved, though he did find some success with it in postseason starts before NLCS Game 7.

Pfaadt's use of four-seamer

- First 6 starts: .339/.391/.645 (-8 run value)

- Since last recall: .316/.358/.653 (-3 run value)

The solution, then, is clear: Just don’t throw it as often. Or, if we can paraphrase the all-timer of a quote Strom offered Theo Mackie of the Arizona Republic in August about why Pfaadt was throwing fewer fastballs: "Because he was [expletive] told to do so."

No kidding. In Game 7 of the NLCS, Pfaadt threw the four-seamer only 16 times, a career-low 25% usage. (It still bit him: Pfaadt allowed a walk, a double and an Alec Bohm homer on the pitch, and the only out came on a sacrifice bunt.)

“Brandon threw the baseball as good as you possibly could have hoped or imagined,” manager Torey Lovullo said after Game 3 of the NLCS. “Once again, it’s a young kid stepping into a huge environment and executing at a very high level. That’s what stands out more than anything.”

Lovullo chose not to let Pfaadt go deeply in any of his starts, likely correctly, in deference to Pfaadt’s truly massive third-time-through-the-order splits, though it’s difficult to know if those still apply to such a magnitude given the changes he’s made -- in August and September, batters facing him the third time through were more “strong” than “legendary,” as they’d been in May and July, and he hasn’t been allowed to face one yet in October.

Pfaadt now owns two of the top five spots on the list of most swing-and-misses in a postseason game by a rookie. He’s not Scherzer, in terms of resume; he’s not even Gallen or Merrill Kelly, in terms of 2023 production. But Pfaadt is not the rookie who was so ineffective he couldn’t hold a Major League roster spot earlier in the season, either. He’s someone who can keep his team in a postseason game, at least the first half of one. Pfaadt might just be someone who can help them win a World Series.