Bryce Harper “had a very good year … I don’t think he had an elite year,” said Phillies president of baseball operations Dave Dombrowski earlier this winter.

While Dombrowski wasn’t really incorrect in that statement – Harper did hit 27 homers, but failed to earn a place either on an MVP ballot or the All-Star team for the first time in a full season since way back in 2019 – it’s certainly the kind of comment that’s going to draw some attention.

It did, obviously. Harper later posted a video of batting practice over the holidays where he was prominently wearing a “not elite” shirt, and Dombrowski had to scramble to explain what he’d meant. Whether he intended his comment as a motivational tool or if it was simply more honesty than you’d expect from a modern front office executive, it’s clear that Harper has taken it to heart.

Given Harper’s importance not only to the Phillies lineup but also to his own legacy as a nearly-certain future Hall of Famer, it’s a pretty important question as he heads into his age-33 season, which will somehow be his 15th in the Majors.

“Can he rise to the next level again?” Dombrowski had said. “I don’t really know that answer. He’s the one that will dictate that more than anything else.”

Quite right. Let’s find out.

Wait, did Harper really have a disappointing year?

No! Not by the standards of mere mortals, anyway. Harper added another 3.5 WAR to his career total (now 55.6, per FanGraphs), and his 129 OPS+ (which is “29% better than average”) ranked him tied for 36th among the 215 batters who took at least 400 plate appearances. That is, scientifically speaking, “really good.” He out-hit Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Cody Bellinger, Alex Bregman, and Gunnar Henderson.

It’s also the weakest year he’s had since 2019, his first year with Philadelphia, and even that season won’t be seen by everyone as being worse than 2025 despite the mildly lower OPS+ of 126, because he drove in 114 runs that season. If “36th in OPS+” is still quite good, it’s also not “ninth,” which is where he ranked among qualified hitters over the previous five seasons. “Good, but not elite,” as Dombrowski said. Well, yes.

It mostly says a lot about how spectacularly Harper has performed in the past that he can hit 27 homers, produce better than all those stars we just named, and the end result is still worry about what (if anything) is going wrong. You have to be really, really good to earn that kind of reaction.

OK, so he was still really good. Why wasn’t he as good as he’d been before?

Harper did miss almost all of June with a right wrist injury, which likely cost him what would have been a sixth 30-homer season, and that mark alone might have changed the narrative here. So there’s that, but it also reportedly was bothering him for much of 2024, when he was excellent.

That aside, let’s quickly knock off the reasons that aren’t here.

- No, he didn’t strike out more. He actually dropped his K-rate slightly, from 22% to 21%.

- No, he didn’t hit the ball less hard. His hard-hit rate was in the 77th percentile, in line with previous years.

- No, his bat isn’t slow now. His bat speed was identical in 2024 and 2025, in the 81st percentile.

- No, it wasn’t ‘bad luck.’ Harper’s expected stats and actual ones were close to identical.

Those are the obvious areas of worry to check, and there’s nothing there. You might next look at a hitter’s home park to see how it played, and it’s indeed true that Citizens Bank Park has played less hitter-friendly as the years have gone on – the wind is an underrated factor there – but considering that Harper had a .941 OPS there last year against a mere .760 mark on the road, it’s pretty clearly not about his home field, either.

That’s all what it’s not. He still performed worse, so what was it?

Wait, we’ll get back to that in a minute, there’s a more important question to answer first.

This is all because he’s not getting as many pitches to hit due to lack of protection in the lineup, right?

Sort of, but not exactly, and also mostly no.

It’s definitely true that Harper doesn’t get a lot of great pitches to hit, with his 43% in-zone pitch rate being the lowest (!) of any qualified hitter. “A glaring element of this is that, of anybody in baseball, he gets the least amount of pitches to hit,” said Harper’s agent, Scott Boras, and he’s completely accurate to say it.

But that’s always been true. When Harper won the NL MVP Award in 2015, his in-zone rate was also 43%, and it was also the lowest of any qualified hitter. Between 2016 and ’24, his in-zone rate was 44%, still the lowest of any qualified hitter. This has essentially always been the case.

The reason that’s happening isn’t really because of lineup protection, which has been a huge talking point in Philadelphia for some time. It came up a lot when Harper, who had been hitting ahead of Kyle Schwarber before his wrist injury, returned to hit behind Schwarber, usually with J.T. Realmuto or Alec Bohm behind him. There are things to like about each of those players, but they’re not Schwarber, either. And yet …

- Zone rate (April/May): 42.5%

- Zone rate (July-Sept.): 43.6%

If anything, Harper saw slightly more strikes after Schwarber moved from behind him in the lineup to ahead. That actually makes sense, as we’ve long known that protection comes from ahead, not behind. But it’s a barely perceptible change, and again this is similar to Harper's entire career. It’s probably not about lineup order.

So what is different, then?

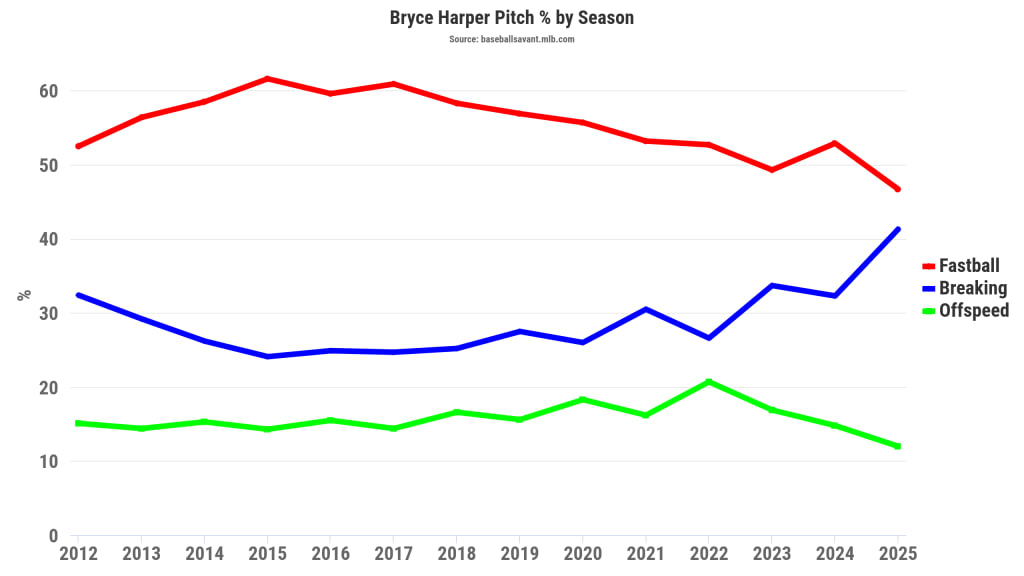

OK, so if the "pitches to hit" issue isn’t really a new one, what is new is that the kinds of pitches he’s seeing have changed a lot. It’s been known for years that pitchers have been using fastballs less often in favor of pitches that move, and so that means that pretty much every batter has seen an increase in breaking balls. But for Harper, it’s been more than just a small increase.

Only three batters with regular playing time saw a higher breaking ball rate than Harper did, and two of them – Nick Castellanos and Jorge Soler – can charitably be described as “readily willing to chase outside the zone.” The average Major League hitter saw 31% breaking balls last year, a mark which ticks up a portion of a point annually. But Harper has seen his breaking ball rate jump up from 26% in 2022 to 41% last year, a massive increase. Throw in the offspeed pitches, and Harper now sees a fastball less than half the time, one of the lowest rates in the game.

See if you can understand why.

- Harper's wOBA vs fastballs, 2021-25:

- .478, .409, .413, .412, .397

- Harper's wOBA vs breakers, 2021-25:

- .336, .351, .342, .323, .319

Over the last five years, Harper has been an elite fastball masher, ranking sixth in wOBA – that’s Weighted On-Base Average, you can think of it like OPS – behind four future Hall of Famers and the man who just had one of history’s greatest rookie years, Nick Kurtz. While he’s hardly inept against breakers, there’s a gap of 50 or more points every single year there; over the last two seasons, he’s 79th against breaking balls, similar to non-mashers Xavier Edwards or Jake Cronenworth.

So, to some extent, it’s just that: Scouting reports have reacted to how to pitch him, and he’s yet to show he can react back. Until he does, expect to see an otherworldly amount of spin.

Anything else?

Always. As we said: Harper never sees good pitches to hit. What’s different, if somewhat inconsistent, is that he was once fantastic at laying off of them, ranking at various points in his career as a well-above-average chase rate kind of guy. That’s no longer true, and hasn’t been for some time, as he’s now quite willing to go outside the zone to find something to hit. That’s generally a hard way to succeed, and it was no different for Harper, who hit .182 with three homers outside the zone last year.

Here’s the trick, though: For all the talk about what happens outside the zone, Harper’s performance on pitches inside the zone was weaker than it had been since 2016. That, again, was still well above the Major League average, because he’s still a very good hitter.

“A good pitch to hit” isn’t always the same thing as “a pitch in the strike zone,” though it’s a decent proxy, but some of this simply comes down to “do damage when you get that pitch.”

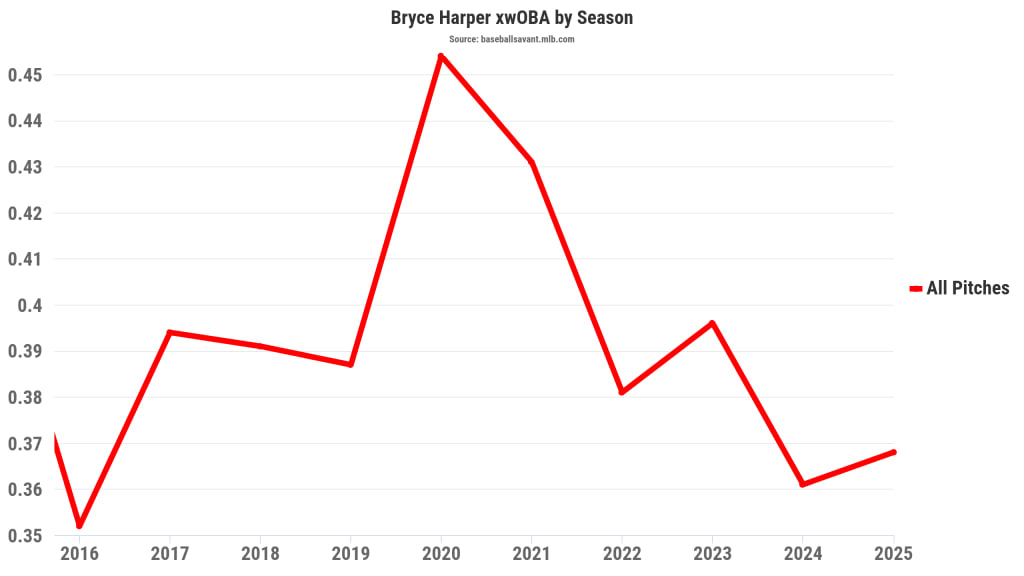

Is this just what it looks like when you’ve been in the Majors for 14 seasons?

Oh, well … kind of, yes.

Rick Ankiel was Harper’s center fielder the day he debuted, against a Dodgers team that started Chad Billingsley on the mound. It’s been a long time, is the point, and if we look at a fancier Statcast metric like expected wOBA, which looks at quality of contact as well as quantity of contact, well, that’s sort of the shape you’d expect to see. Giving 2020 the appropriate grain of salt for how short it was, that was also his age-27 season, long considered at or near a hitter’s peak. No one stays great forever, not even the greats.

So can he be elite again in 2026?

Well, sure. We’re talking about a hitter coming off a really good season, or a great season for most hitters. The core measurable skills are all there. A little less chase here, a little more damage on hittable pitches there, and we’re not that far away from another Extremely Good Harper season, even if it gets a little less likely each year that we’ll ever see MVP Harper again.

The current projections, for example, roundly expect Harper to hit 30-to-35% better than average in 2026. It would be his 10th consecutive outstanding year. If this is the beginning of the end, we should all be so lucky. It might take a while to get here.