The leaderboards are at once familiar and foreign.

We know the names of American and National League legends like Walter Johnson, Babe Ruth and Bob Feller. And of Negro League legends like Bullet Joe Rogan, Turkey Stearnes and Cool Papa Bell.

But to see these names unseparated by the sin of segregation and actually alongside each other on lists of season or career leaders for batting average, homers, wins, innings, etc. -- all under the same league umbrella -- is staggering.

This was baseball as it ought to have been. And it happened in a little-known circuit called the California Winter League.

Thirty-seven years before Jackie Robinson integrated MLB, the California Winter League (CWL) added not just a Black player but an entire Black team -- Rube Foster’s traveling Leland Giants. And from 1910 until the league folded in 1947, that’s how it was, with Black teams and eventually Negro League teams playing against and, in many seasons, dominating white teams that included scores of AL and NL players. The teams themselves were still segregated, but at least the league allowed Black players to compete on the same stage as their white counterparts.

“It gave the country a rare look at high level integrated professional baseball,” author and researcher William F. McNeil wrote in his 2002 book on the league, “more than 25 years before organized baseball got the message.”

McNeil’s book, “The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League,” is the best, most comprehensive resource for information about a league not typically cited or studied (even the excellent, vast resource that is Baseball-Reference is mostly blank when it comes to the CWL). And as the recently formed Negro League Statistical Review Committee continues the important -- and complicated -- process of incorporating Negro League numbers into the official MLB register, it’s fascinating to look at a league where no such after-the-fact incorporation is required.

The CWL’s players had done that work already, when they opposed each other on America’s most significant integrated baseball stage of the early 20th century.

* * * * * * * *

The first instance of formal segregation in baseball occurred in 1867.

This was two years after the Union had defeated the Confederacy. The Civil War’s turning point occurred in the state of Pennsylvania, at Gettysburg, and Pennsylvania produced more Black soldiers than any other state in the Union. Yet it was a Black baseball team in the Keystone State that prompted the sport’s first official environment of exclusion.

As baseball’s rules became standardized in the mid-1800s, teams sprung up throughout the United States. And when Black men were excluded from joining white teams, they formed their own. One of these was Pennsylvania’s Pythian Base Ball Club, which went 10-1 in its first full season in 1867 and became a big draw in the Black community. On the heels of that success, the Pythians were one of 266 clubs to apply for membership in the Pennsylvania state chapter of the National Amateur Association of Base Ball Players.

At the Pennsylvania State Convention of Base Ball Players, 265 applications were accepted.

You can guess which one was not.

So it went as the early Majors emerged.

The only Black player in the nascent National League is believed to have been William Edward White, the son of a plantation owner and his slave. White passed as white and played in a single game for the Providence Grays on June 21, 1879. In 1887, Cap Anson and the Chicago White Stockings refused to take the field for an exhibition opposite Black players Moses Fleetwood Walker and George Stovey of the International League’s Newark Little Giants. And on July 14 of that year, the International League voted to ban the signing of Black players to new contracts.

That’s how the color line was born.

Though a number of Black players competed in the fledgling Minor Leagues in the 19th century, none of the attempts to integrate the Major Leagues from the 1890s up until Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers on April 15, 1947, were successful. There were instances of Black teams competing in otherwise white leagues (notably, the 1890 York Colored Monarchs were running away with the Eastern Interstate League before the rest of the league voted to disband). And the Cuban Winter League, which was active from 1878 to 1960, had Black players wintering in the island nation and competing in the first half of the 20th century.

But in the U.S., by the end of the 1890s, Black professional players had to play on all-Black teams, and any games between Black and white teams took place outside the channels of “organized baseball,” typically on barnstorming tours. This would not change, of course, until Jackie came along.

That’s what makes the open-mindedness of the California Winter League so remarkable. In the first four decades of the 20th century, it was the only professional league in the country in which Black players and white players of Major League caliber competed against each other in something other than scattered exhibitions.

Back in the early 1900s, baseball was a budding enterprise in the Golden State, which, for Black teams, became a land of opportunity.

* * * * * * * *

The seeds of western migration that would eventually lead to the Giants and Dodgers relocating and setting off a baseball boom on the West Coast were sown in the Bay Area, where bankers and businessmen who had moved from the northeast formed various amateur teams.

By 1869, the baseball scene was legitimized enough to attract a visit from the Cincinnati Red Stockings. The first professional team walloped the boys from the Bay (they were beating a team named the Atlantics, 76-5, before it was mercifully called off in the fifth inning). But this was a key step toward the California clubs understanding what it took to play at a pro level.

California’s first pro league, the Pacific Base Ball League -- featuring four teams from San Francisco -- was formed in 1878. The rival California League formed a year later, and the first iteration of the Pacific Coast League followed in 1887.

Southern California first got in on the action with the 1892 formation of the Los Angeles Seraphs (later, the Angels… though of course not the Angels franchise we know today), who won a California League pennant in their inaugural season. And when Major League teams began playing exhibition games up and down the coast in the 1890s, the concept of a winter baseball league took shape.

The first California Winter League had a false start in 1895, when it formed and folded within a month, and a Northern California Winter League came to be in 1897. By the early 20th century, there were both northern and southern circuits, but the latter emerged as the most popular league because of the warmer climate and ability to attract the country’s best players. (Walter Johnson pitched for Santa Ana in consecutive winters from 1907-08 through 1909-10, leading the league in wins twice and helping the Yellow Sox to a league championship in his first season.)

But things really get interesting when we get to the winter of 1910-11.

That’s when Rube Foster, who in 1920 would organize the first Negro National League, brought his traveling Leland Giants to California to participate in the California Winter League. Foster’s roster, which included future Hall of Famer Smokey Joe Williams, made its presence known by fishing second behind the champion San Diego Griefers.

After a year hiatus, Foster returned to California in 1912-13, this time with his Chicago American Giants. And in 1915-16, Foster’s club won the league championship with a roster that included not only Smokey Joe but another Hall of Famer in shortstop Pop Lloyd.

Of course, just because these Black teams were accepted in and successful in the CWL didn’t mean racism and segregation didn’t rear their ugly heads on the West Coast.

In the spring of 1914, the American Giants had scheduled a barnstorming tour in the northwest, including a series of exhibitions along the coast, against the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League -- a team managed by Walter “Judge” McCreadie. San Francisco Seals owner J. Cal Ewing spoke out against the plan.

“If I were a player, working for McCredie,” he said, “and he asked me to go out and play against these colored fellows, I would refuse to do it for him.”

PCL president Allen T. Baum agreed and insisted that PCL teams should not play games against Black teams or allow Black teams to use their parks.

This had a domino effect on the CWL, which primarily used PCL parks for its games. By 1917, Baum’s decree had filtered down to the Los Angeles-area clubs. The facilities available to Black teams were too small to generate enough attendance and revenue to make the trips feasible, so there is no record of Black teams participating in the league from 1917-19 (on the flip side, there is a record of Babe Ruth suiting up for a few games in the winter of 1919-20). The league itself faced extinction.

But whereas the adversity created by the PCL ban could have spelled the CWL’s demise, it instead led to its heyday.

* * * * * * * *

Now a gentrified, “it” neighborhood where upper-class Los Angelenos flock, Boyle Heights, on the city’s east side, has a dramatic, diverse history.

When Los Angeles was still under Mexican rule, in 1845, the Indigenous group known as the Tongva was displaced and relocated to an area on the east bank of the Los Angeles River then known as El Paredon Blanco (The White Bluff). After Los Angeles was seized by American forces, the site was razed to the ground in 1847, and 22 acres of the land were purchased by an Irish immigrant named Andrew Boyle, who would inspire the name Boyle Heights.

In the late 1800s, Boyle Heights was primarily home to the large estates of affluent, white Protestants. But in the early 1900s, as those residents divided their estates into smaller parcels and sold them off at more affordable prices, it became an immigrant enclave. Boyle Heights was one of the few communities in the area that did not have housing restrictions against non-whites. So it became home to thousands of Eastern European Jewish immigrants and people of Mexican, Japanese, Armenian, Italian, Russian and Black descent. An American melting pot had come to Boyle.

This, appropriately, was the place where the integrated baseball of the California Winter League thrived for a time. You wouldn’t know it to look at the section of East Fourth Street that now houses a food distributor and an electrical supply store, but Boyle Heights was once a bastion of Black baseball.

Two men were responsible for that. The first was a Black entrepreneur named Doc Anderson, who came to the rescue of the sagging CWL by building Anderson Park, which came to be known as White Sox Park, at East Anderson and Fourth Streets, in 1920. This became home to the league’s annual Black team.

Four years later, a nightclub owner named Joe Pirrone, who had played briefly in the Minor Leagues and was a strong supporter of the league and its integration concept, replaced the primitive White Sox Park with the (slightly) more permanent White Sox Park II, which held about 3,500 fans.

With the Boyle Heights base established for the Black teams, the 1920s became a golden era for the Golden State’s winter circuit. The style of play gradually elevated from what McNeil estimated to be A-ball quality early in the century to something closer to what we would consider Triple-A. Anderson assembled some terrific Black teams, including a 1920-21 unit that featured Rogan, Dobie Moore (a would-be Hall of Famer profiled here), Rube Curry, Hurley McNair and more. The following year, the legendary Oscar Charleston suited up for a team known as the Colored All-Stars in the CWL.

“Some, if they were only white,” wrote the Los Angeles Times of the Black players in the CWL, “would be stars of the first magnitude in the Major Leagues.”

* * * * * * * *

With Pirrone, who had previously pitched in the CWL, recruiting players from across the country for a white squad called Pirrone’s All-Stars, the level of talent was strong on both sides. In 1920, Pirrone’s club had seven position players and four pitchers who had appeared in the big leagues the previous season and three more players who would become full-time big leaguers the following year.

In a typical year, the league consisted of four teams -- three white and one Black. Games were played on Saturday and Sunday afternoons and on holidays.

“It kept the money flowing,” Negro Leagues researcher Phil S. Dixon said of the CWL. “The money that Black players got in those days was just not like the money the white teams got. So that was a way to supplement your income.”

In his conversations with Negro League players before they passed, Dixon heard stories of other supplemental income that emanated from those winters in California.

“One time, I was out in Los Angeles, and Chet Brewer took me to Buster Haywood’s house,” Dixon recalled. “We’re sitting there talking, and Buster says, ‘Chet, did you tell him you’re in the Tarzan movie?’”

Dixon was floored.

“They would go out there and sometimes they were extras in movies,” he said with a laugh. “I said, ‘Chet, which movie was it?’ But I couldn’t get any more out of him.”

(Dixon also heard a story of Mule Suttles appearing as an extra in the Mae West movie “I’m No Angel.” He bought the DVD and looked hard for Mule, to no avail.)

Because of the opportunity and paychecks available, the CWL had no trouble attracting some of the biggest names in the Negro Leagues, including the powerful 1925 Philadelphia Royal Giants -- a squad that included Rogan, Biz Mackey, Rap Dixon, Newt Allen and Crush Holloway.

That club defeated a team called the White Kings to win the league championship -- the first of 13 CWL titles for a Black team in a 16-year span.

The 1927 CWL season was disrupted by an edict from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis that prohibited Major League players from participating in the league, effective Oct. 31 of that year. The league started play a couple weeks early so that a few such players, including Bob Meusel and Babe Herman, could play a handful of games prior to Landis’ deadline. The white teams then had to rely on former big leaguers and Minor Leaguers the rest of that winter, and, in ensuing years, the league had to work around demands that big leaguers only be available to the CWL for 15 days after the conclusion of the Major League season.

In the late 1920s, a third iteration of White Sox Park was built, at Compton and 38th Streets. And here, the concept of night baseball -- an innovation adopted by the Kansas City Monarchs in 1930 -- was eventually brought to the CWL, with White Sox Park illuminated for weeknight games to attract more crowds.

The Black rosters continued to be lit up by luminaries like Suttles, Satchel Paige, Turkey Stearnes, Cool Papa Bell, Wild Bill Wright, Double Duty Radcliffe, Willie Wells and Dan Bankhead (who would go on to become the first Black pitcher in the AL/NL). A true who’s who of Black baseball, and the white teams in this era were routinely overmatched. (Though the San Diego Gold Club in the late 1930s did have a pretty good outfielder -- a Minor Leaguer named Ted Williams.)

Alas, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, put an abrupt end to that CWL season and was part of a series of changes that would ultimately bring about the league’s demise. The talent level of the league was severely depleted during the war years.

The CWL had one last burst of interest in the mid-to-late 1940s. In 1945, as rumors spread of Jackie Robinson potentially signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Pasadena native suited up for Brewer’s Kansas City Royals in the CWL and had his every move followed intensely by the press.

“Paced by the peerless all-around play of shortstop Jackie Robinson,” wrote the Pittsburgh Courier, “the Kansas City Royals opened the annual winter league exhibition series Sunday with a 4-2 victory over the Service All-Stars at Recreation Park in Long Beach. An overflow crowd attended. Robinson hit a homer inside the park, and was riot on the paths and fielded brilliantly.”

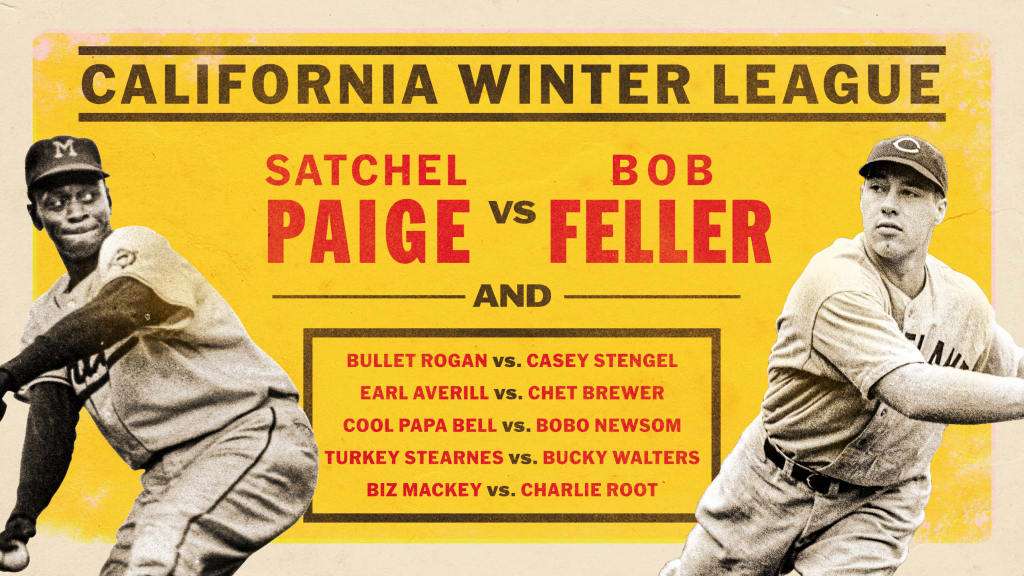

Speaking of brilliant, future Cleveland teammates Paige and Bob Feller had some fantastic pitchers' duels in the CWL in the fall of 1945, ’46 and ’47.

But as was the case with the Negro Leagues, integration in the AL and NL spelled the end of the CWL, which wrapped in 1947.

Also like the Negro Leagues, records of the CWL are inevitably incomplete. McNeil’s book, crafted with the help of newspaper research by Society for American Baseball Research member Walt Wilson, is the closest thing we have to a complete document, and it includes appendixes with a bevy of statistics.

Peer through the leaderboards in the book, and you’ll see fun things like a career strikeouts list topped by Satchel Paige (766), Bullet Joe Rogan (351) and Walter Johnson (321). And you’ll see Babe Ruth leading the league in home runs (with one) in 1919, followed by Rogan (five) and Biz Mackey (four) the next two years.

We’ll never know what the AL and NL leaderboards would have looked like had Black players been permitted to participate at that time. But the surviving accounts of the California Winter League give us a taste of integrated baseball as it could have -- and should have -- been.