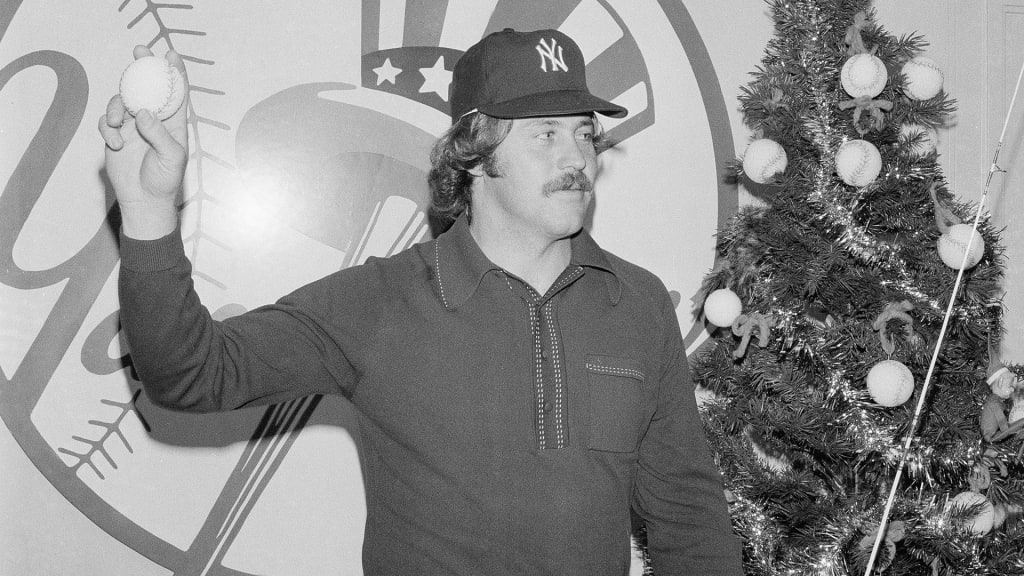

It was 47 years ago, New Year’s Eve of 1974, that baseball changed forever. That was the day that Jim "Catfish" Hunter left the Oakland A’s after an arbitrator named Peter Seitz ruled that the A’s had violated Hunter’s contract by not paying him money he was owed.

In that moment, Hunter -- one of the great pitchers of his time -- became baseball’s first free agent. Ring out the old. Ring in the new.

Hunter signed with the Yankees on a five-year, $3.25 million contract. He may not have fully understood how baseball had been changed forever because of Seitz’s ruling, a year before Seitz essentially ended baseball’s reserve clause, which had previously bound players to their teams until, and unless, they were released. But baseball had changed forever, years after a brave man named Curt Flood had his career end when he challenged the reserve clause all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I hung up the phone,” Hunter said at the time when he learned of the ruling, “and turned to my wife and said, ‘We don’t belong to anybody.’”

Hunter eventually pitched in three World Series for the Yankees, after winning three straight championships with the A’s from 1972-74, before coming to New York. Much later, he became another champion Yankees player afflicted with ALS, the way Lou Gehrig had been, dying at the age of 53 back home in North Carolina.

But after making such fine history in Oakland -- in the Fall Classics and with four straight 20-win seasons -- Hunter made a different kind of history off the field in New York on New Year’s Eve, where the big news on that night wasn’t just a ball dropping in Times Square.

Hunter probably didn’t think he was changing the world because an arbitrator ruled in his favor. But that is exactly what he did.

The money Hunter made when he signed that night at the Yankees’ old offices in the Parks Administration Building (in Flushing, Queens, of all places) seems quaint in comparison to the money modern free agents now make. But it was huge money at the time, ending what the New York Times called “the most celebrated bidding war in American history.”

All because the quiet man from Hertford, N.C., didn’t legally belong to anybody after it was ruled that he could leave Charlie Finley’s A’s and make his own choices about where he wanted to pitch next.

One of the ironic parts of this story -- still such a huge story and turning point in baseball history -- is that even though it was the beginning of the way George Steinbrenner would also change baseball forever, Steinbrenner was suspended from the game at the time because of illegal contributions to the Richard Nixon presidential campaign (a felony for which he was eventually pardoned). So Yankees team president Gabe Paul was the point man in the negotiations. But before Steinbrenner had gone off to serve his suspension, he’d said this to Paul:

“Any time you have the opportunity to get control of a player for cash, go ahead.”

Not long afterward, with Steinbrenner back in control of the Yankees and starting to throw money around, he signed Catfish Hunter’s old A’s teammate, Reggie Jackson, to a five-year contract with a total value of $3.5 million.

Jackson kept winning in New York the way he and Hunter -- whom Jackson once described as the “boss” of the old A’s -- had won those three World Series titles in Oakland. Jackson wanted New York and the stage of Yankee Stadium, the same as Hunter did before him.

“I believe there were higher offers,” Hunter said after signing his contract, “but no matter how much money was offered, if you want to be a Yankee, you don’t think about it.”

So the Yankees beat out the Pirates, Dodgers, Padres, Royals, Expos and Cleveland for Hunter’s services. Hunter had arm troubles in New York and was diagnosed with diabetes, and he only occasionally looked like the pitcher who had gone 88-35 over his final four seasons with the A’s.

Hunter was afraid his career might be over in the summer of 1978, because of shoulder problems. Then, he underwent a 10-minute, non-surgical “shoulder manipulation” at the hands of Yankees team doctor Maurice Cowen. One last time, Hunter was freed up in a different way.

Hunter came back to the Yankees that July, when they were still 13 games behind the Red Sox in the American League East. If he wasn’t the Hunter of old, he was close enough. There is no way that New York would have caught Boston during that unforgettable summer, or go on to win its second World Series title in a row, without Hunter pitching the way he did down the stretch.

Hunter went 2-9 with a 5.31 ERA in 19 starts in 1979, before retiring at the age of 33. Still, he made it to the end of a contract that we’re remembering today, because that contract ought to be remembered.