When Charles Bronfman was a kid growing up in Montreal, he had a favorite baseball diamond he liked to play on. Now, being an heir to the Seagram whiskey fortune, it was built on a lot between his parent's home and his uncle's. They tore down the house in between to construct a playground that included a backstop and a home plate. Still.

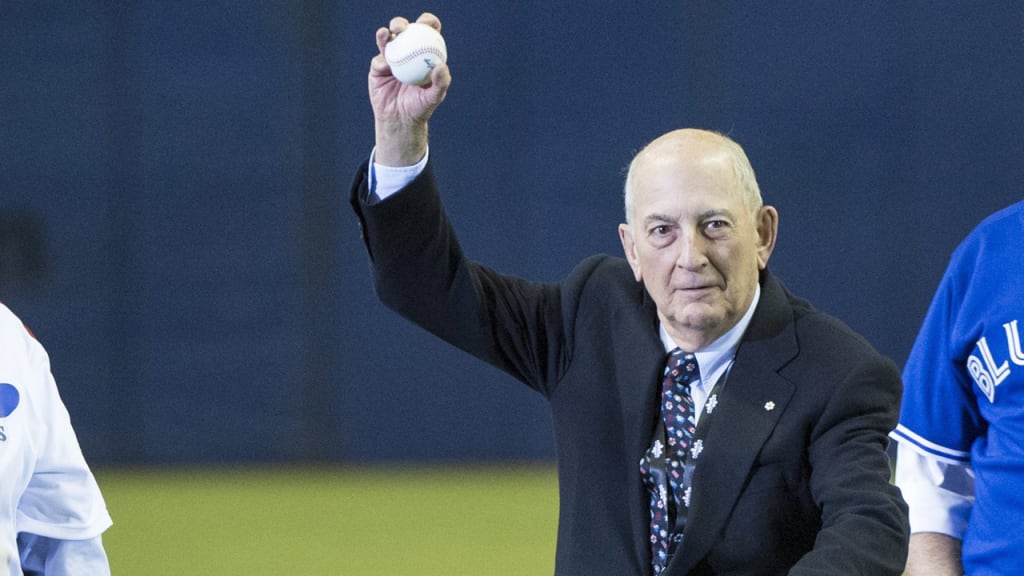

Bronfman, best known to baseball fans as the first owner of the Expos, is in his 80s now. And he's authored a book. "Distilled: A Memoir of Family, Seagram, Baseball, and Philanthropy."

The reality is that the baseball was a relatively small portion of Bronfman's life, and just one chapter in his autobiography is devoted to the sport. Yet, he makes it clear that the national pastime of the United States had an outsized impact on him even though he spent most of his life living in Canada.

Bronfman was deeply involved in the Expos from the time he agreed to become an investor in 1968 -- the team began play the following year -- until selling the club in '90. And the positive ripple effects of that experience reverberate throughout the pages.

Bronfman's decision to invest in baseball was made on his own, not as a member of a dynastic family that included a domineering father and a far more extroverted older brother. He further admits that for all his advantages, he could be uncomfortable in social situations and sometimes had trouble asserting himself.

"It wasn't until the Expos, in my mid-30s, that I was self-assured enough to talk to people, because I could talk about baseball," Bronfman wrote early in the book.

It's a thought Bronfman repeatedly returns to as he tells his story.

"I didn't start to gain positive traction until I invested in the Expos," Bronfman said in his concluding remarks.

There were other pluses to buying in.

"Aside from being a sports fan, I thought it would be good for the city, the province and the country," Bronfman said. "It would be something else for everyone to root for, a potential unifying force."

Bronfman wasn't unaware, either, of how much business Seagram did south of the border.

"I also liked that it would thicken our ties to the United States," Bronfman said.

At one level, the Expos chapter illustrates how far Major League Baseball has come since since Bronfman was involved. Back then, Montreal was awarded a franchise without an adequate stadium or even any committed investors.

Still, this can also be viewed as the first tentative step toward the internationalization of baseball, a process that has since grown to include such ambitious projects as the World Baseball Classic and regular-season MLB games being played in Mexico, Japan, Puerto Rico and Australia.

Even then, though, there were examples of how baseball could transcend national boundaries. Bronfman pointed out that former Canadian prime minister Lester Pearson, who attended the party to celebrate the birth of the first MLB franchise outside the United States, was a huge fan.

"The story was that while Pearson was in office, if the World Series was on and there was an afternoon game, he wouldn't have any appointments so that he could watch the game," Bronfman said.

Bronfman provides a lively reminiscence of his Expos years. He's particularly proud of choosing the tricolored "beanie" caps, noting that they can be seen on the streets of Montreal to this day. Bronfman also covers the first Spring Trainings in West Palm Beach, Fla., braving the cold at homely little Parc Jarry before moving into Olympic Stadium and the challenges of keeping star players in Montreal, especially as the free agency arrived and the exchange rate with the U.S. dollar worsened.

There is plenty here, too, for those who aren't interested in sports. Bronfman's recollection of growing up in a family that possessed fabulous wealth is fascinating. He is engagingly honest about his own shortcomings and the family disputes that cost them their heirloom company. Bronfman makes a compelling case that giving away millions isn't as simple as it sounds.

And when it came to wrapping up his remarkable life, to putting it all in perspective, Bronfman returned once again to baseball for the summation.

"As I know from my baseball days, no one bats a thousand," Bronfman said. "But as I look back, I'd say that I have a damn good batting average."