MLB.com is celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month by highlighting stories that pay tribute to some of the most significant and talented players from Latin America in the game's history.

---

Neither Liván nor Orlando Hernández can claim the title of “best Cuban pitcher in Major League history.” That distinction best suits Red Sox legend and Hall of Famer Luis Tiant. Neither right-hander took home a Cy Young Award or an ERA title or led his league in strikeouts in his time in the Majors. Liván was a journeyman who suited up for nine franchises in a 17-year career; Orlando pitched in the big leagues for just nine seasons.

And yet, without many of the accolades we associate with big-time pitchers, the half-brothers loom large in discussions about Cuban participation in the Major Leagues -- both because of their personal sagas as defectors who risked it all for a chance to pitch in the U.S. and because of their instant impact during the month when legends are made: October.

'I Love You, Miami'

Prior to the 1990s, it was rare for a Cuban athlete to defect during international play. That began to change after the Soviet Union, which Cuba was dependent on economically, collapsed in 1989, resulting in severe scarcity and food shortages on the island, a time known as el período especial -- the special period.

In ’91, star pitcher René Arocha became the first ballplayer to defect; he made it to the Majors with the Cardinals in ’93.

Liván Hernández was a 20-year-old prospect representing Cuba at a tournament in Monterrey, México, when he, too, made the decision to flee on Sept. 27, 1995. He made his way to the Dominican Republic, and in January 1996, less than four months after he snuck out of his team hotel, he signed with the Marlins -- South Florida offered the comfort of a large Cuban community -- for four years and $4.5 million. He made his Major League debut in September of that year and became a full-time member of the Marlins’ rotation in June ’97.

In his rookie season, Hernández impressed with his ability to deceive hitters by mixing pitches and posted a 9-3 record (and started 9-0) with a 3.18 ERA and 72 strikeouts in 17 starts for the Marlins, who made the postseason for the first time in their five-year history as the National League Wild Card team.

It was in the NL Championship Series against the Braves that Hernández truly made a name for himself, however. After pitching in relief in Game 3, he drew the start in Game 5. Dueling against future Hall of Famer Greg Maddux, Hernández set an NLCS record with 15 strikeouts (albeit, it has been noted, with the aid of a generous strike zone from home-plate umpire Eric Gregg) and pitched a complete game. The Marlins won 2-1 en route to capturing the National League pennant.

Hernández was named NLCS MVP.

“He just had everything going,” Hernández’s manager at the time, Jim Leyland, recalled in the ESPN 30-for-30 documentary "Brothers in Exile" about the Hernández brothers that aired in 2014. “He just totally overmatched them.”

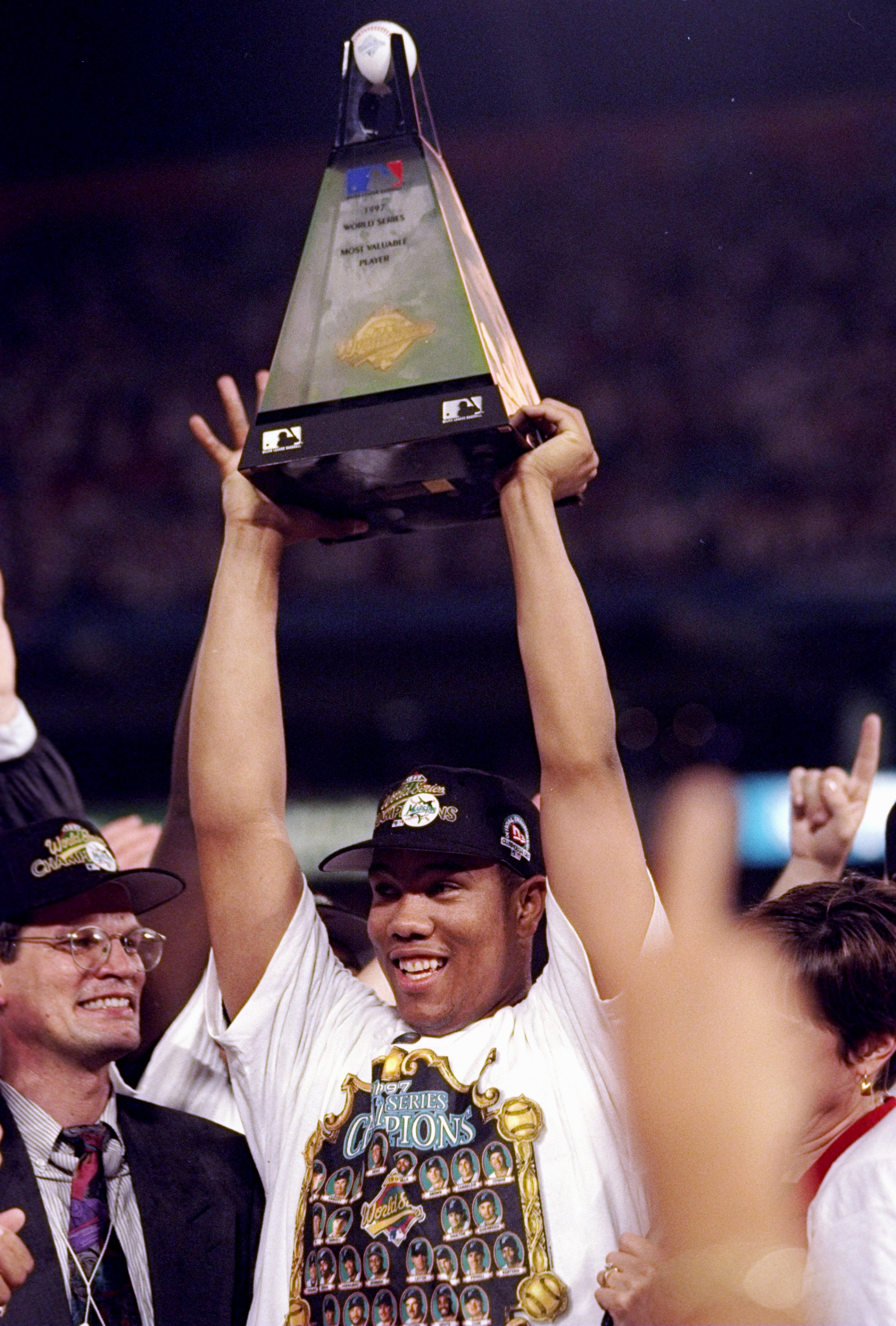

Hernández had pitched in just 18 regular-season games before he took the mound for Game 1 of the 1997 World Series against Cleveland; that’s still the record for the fewest regular-season appearances before a Game 1 start in the World Series in MLB history. After earning the wins in Game 1 and Game 5 to help the Marlins win the series 4-3, Hernández became just the fourth player to be named MVP of both the League Championship Series and World Series in the same year, and the first rookie to achieve the feat.

When he defected, Hernández had left behind his mother, Miriam Carreras, who didn’t get to see him pitch in the World Series. But the Cuban government allowed her to travel to Miami for Game 7, thanks in part, presumably, to a letter Hernández’s teammates signed asking that she receive permission to attend.

Carreras was there to witness one of the most iconic moments in Marlins history, when her son hoisted the MVP trophy in the air and uttered four words: “I love you, Miami.”

The Duke

Hernández's 1997 performance reminded the baseball world that, even after nearly 40 decades of communist rule, talent in Cuba still ran deep. But Hernández insisted that he had an older brother back home who was even better.

“He was better than me. The best pitcher in Cuba. He won the most games of any pitcher,” Hernández was quoted as saying in an Associated Press story in ’97.

That brother, of course, was Orlando “El Duque” Hernández, of the signature high socks and chin-high leg kick. Liván and Orlando were born to the same father, Arnaldo Hernández, himself a former ballplayer. When Liván defected, Orlando was the ace of the Havana Industriales and considered the country’s top pitcher. His .728 winning percentage (126-47) was a record in Cuba. Following Liván’s flight, however, Orlando came under scrutiny from the Cuban government. Considered a threat to defect, he was barred from playing baseball.

In 1997, the day after Christmas, Orlando followed in his brother's footsteps when he and seven other people got into a watercraft and left Cuban waters. The party made it to a small cay in the Bahamas, where they were picked up by the U.S. Coast Guard. Orlando accepted an offer of asylum in Costa Rica. In March 1998, he signed a contract with the New York Yankees for four years and $6.6 million.

From there, Orlando’s first foray in the big leagues turned out to be almost uncannily similar to his younger brother’s. He made his Major League debut on June 3, 1998, and had a 12-4 record with a 3.13 ERA during the regular season, helping the Yankees win 114 games, then a single-season record.

“I looked up at the stands and saw Cuban flags waving, and I heard the applause, I started tearing up,” Orlando said in "Brothers in Exile," recalling his first big league start at the old Yankee Stadium. “That gave me the confidence to go out and pitch.”

“I just love watching him pitch,” fellow starter David Cone was quoted as saying in New York's Daily News after Orlando’s third Major League start. “He may not know the hitters and all their tendencies, but he knows what he wants to do all the time. … He throws strikes. With that high leg kick, he disguises pitches to the point there’s no way to pick them up.”

But like Liván a year earlier, it was in the postseason where Orlando really made his mark.

'I Love New York'

After a storybook regular season, the 1998 Yankees found themselves in a precarious situation ahead of Game 4 of the American League Championship Series. In need of a win to avoid finding themselves down 3-1 to a powerhouse Cleveland team, the Yankees gave the ball to El Duque, who in his postseason debut was tasked with neutralizing the team that his brother had defeated in the World Series.

It was Orlando’s gem in that game -- he dominated the likes of David Justice, Manny Ramírez and Jim Thome to pitch seven scoreless innings and allowed only three hits to help the Yankees win 4-0 -- that gave rise to his reputation as a big-time pitcher.

“El Duque was special in that game,” said his former teammate, Hall of Fame closer Mariano Rivera, in "Brothers in Exile." "... He looked like he was a veteran for 15, 20 years in the big leagues.”

Orlando later pitched seven innings of one-run ball in Game 2 of the World Series against the San Diego Padres, a game the Yankees won 9-3 on their way to sweeping the Friars. Thanks to an intervention by New York Archbishop John Cardinal O’Connor, Orlando was reunited with his own mother and his two daughters, whom he hadn’t seen since his exit from Cuba, just in time for the Yankees’ victory parade through Manhattan's Canyon of Heroes.

During the festivities, Orlando was briefly handed the microphone, and echoing his brother’s words from a year earlier, he said, in Spanish: “I love New York.”

Orlando won two more World Series with the Yankees, in ’99 and 2000, and a fourth with the White Sox in ’05. He finished his career with a 90-65 record, a 4.13 ERA and 1,086 strikeouts in 1,314 2/3 innings for the Yankees, White Sox, D-backs and Mets. In the postseason, he had a 9-3 record with a 2.55 ERA and 107 strikeouts in 106 innings.

In 17 seasons with the Marlins, Giants, Expos/Nationals, D-backs, Twins, Rockies, Mets, Braves and Brewers, Liván had a 178-177 record with a 4.44 ERA. He was a two-time All-Star, in 2004-05 with Montreal/Washington.

“We started off on the right foot, as they say,” Liván remarked in "Brothers in Exile." “There are players with 20-year careers who never won the World Series. But my brother and I did.”