Darryl Strawberry's Saturday evening is nearly over, but the most important few minutes of it may be just beginning.

Strawberry, 54, who is a Christian minister these days, has just delivered a powerful and emotional sermon on a back field at East Moriches Middle School on Long Island. Over the course of 45 minutes, Strawberry spoke about his struggles with drugs and alcohol, battles that nearly ended his life and turned what appeared to be a Hall of Fame baseball career into something less. He spoke about how finding God saved his life and gave him purpose.

Somewhere in the crowd of about 500 people from Suffolk County -- an area that has lost more people to heroin overdoses than anywhere else in New York State in recent years -- is a man in his mid-20s suffering from addiction. At the insistence of his concerned sister, the man reluctantly agreed to attend the mid-June event, set up by the South Bay Bible Church, and listen to Strawberry.

Desperate to get the man help, the frantic sister walks up to an area in front of the stage from which Strawberry delivered his sermon. She waits while most of the people in the crowd either shake hands with the former baseball star, ask him to sign an autograph or pose for a photo with him, and then she introduces herself.

She's not interested in having Strawberry sign a baseball. She needs his guidance, and more than that, she needs Strawberry to speak with her brother one-on-one. Without hesitation, Strawberry agrees to do so, and he walks with her from behind the school to a huge grass field on the side of the building where the young man is waiting.

With tears in her eyes, the woman introduces her brother to Strawberry, and the three begin to talk while slowly making their way to a parking lot in the front of the school. When they get a few feet away, Strawberry stops.

"You need help," Strawberry said to the man, who had already admitted that he uses heroin every day.

A conversation ensues between a man clearly in denial and a man who has been there.

In the somewhat loud and combative discussion, the man tells Strawberry that he had been in a drug rehabilitation center more than once and that he doesn't want to go back to that specific place.

Strawberry counters quickly.

"I will find the right place for you," he said. "I will make sure that you are in a center that is better than where you were before."

The man comes back with another reason why getting help is not the best option.

"If my mother finds out that I'm using drugs again, she will kick me out of the house," he said. "When rehab is over, I will have nowhere to live."

"Listen to me," Strawberry shouts. "You're not making any sense. You're going to die if you don't get help. I will talk to your mother. I will do everything I need to do to make sure that you can still live with her. But you need to get help."

Finally, the man is silent, and after a few seconds of being stared down by the 6-foot-6 Strawberry, some part of the message has gotten through.

"I will definitely think about it," the man said. "I want to get better."

Realizing that getting the man to consider returning to rehab is as good as he could do that night, Strawberry reiterates part of his message from the sermon and then provides the man and his sister with his contact information.

"It's time to let other people help you," Strawberry said. "It's time to let God into your life. He will set you free. I'm no more important or special than you or anyone else who is dealing with addiction. If God saved me, he will save you."

With the sun beginning to set on the bayside town, Strawberry finally makes his way to the parking lot -- about 20 important minutes after he had originally planned to leave town.

A Friendship in Faith

A day earlier, Strawberry had arrived in East Moriches from his home in Orlando, Fla., where he and his wife, Tracy, have lived for the last few years. Like Strawberry, Tracy is also a minister and spends considerable time discussing her journey from addiction to living a life free of substances.

Tracy is not with Strawberry on this trip to Long Island; she is at another location, speaking to a separate group of people. Instead, Strawberry is in East Moriches with John Luppo and his wife, Christine, and for two days, they are staying at the plush home of Rose Marie Bravo, who formerly ran companies like Burberry and Saks Fifth Avenue, and is now a member of South Bay Bible Church. Bravo and her husband, who are out of town, have lent the home to the church to host Strawberry and the Luppos.

Strawberry initially met Luppo at a Super Bowl party in 2010 and shortly after ran into him again at a birthday party. At the time, Luppo, a longtime Wall Street broker, was struggling with alcohol addiction and what he refers to as "other demons."

"We exchanged numbers," Luppo said over breakfast. "Darryl led me to Christ. Darryl supported me through a lot of things and really helped me understand more about God. A few months after that, he introduced me to my wife, and a year-and-a-half later, he married us."

Today, Luppo serves as the executive manager of Strawberry Ministries. In his role, he books and organizes Strawberry's speaking engagements, most of which are through schools and churches, although prisons have also been on the list of places that Strawberry's anti-drug crusade has taken him. Luppo travels with Strawberry throughout the country and assists him with just about every detail imaginable.

Before working together, the two became close friends.

"We had similar stories," Luppo said. "He was a successful baseball player, and I was a big success on Wall Street. But we were also both addicts, and there was something missing in our lives. Maybe it was an identity crisis where we didn't know who we truly were. We were both able to fill that hole with God, and God replaced those anxieties or frustrations.

"Darryl and I are like the two characters in the movie Twins," Luppo continues. "He's 6 foot 6, and I'm 5 foot 4. We come from different worlds, but we have a common father in God and we have a common bond, which is what we both went through. We both had it all and then lost it all, and now we are brothers in Christ. We both care about helping others, and we want to let as many people know that there's help out there if you have a drug problem."

As breakfast wraps up, a young boy and his father walk up to Strawberry, who is leaning back in his chair with a cup of coffee in one hand. The boy asks Strawberry for an autograph, and the former ballplayer -- who spent parts of five seasons with the Yankees, winning three championships -- gladly signs a piece of paper.

"I've never seen him so relaxed," Luppo said. "He's really at peace with everything in his life."

A Life of Ups and Downs

After their breakfast, the group drives back to Bravo's home. They navigate their way down a long private driveway that leads to a brown house. When they arrive, Luppo opens the front door into a screened-in porch.

Strawberry looks at his watch and realizes that he has several hours before that evening's sermon.

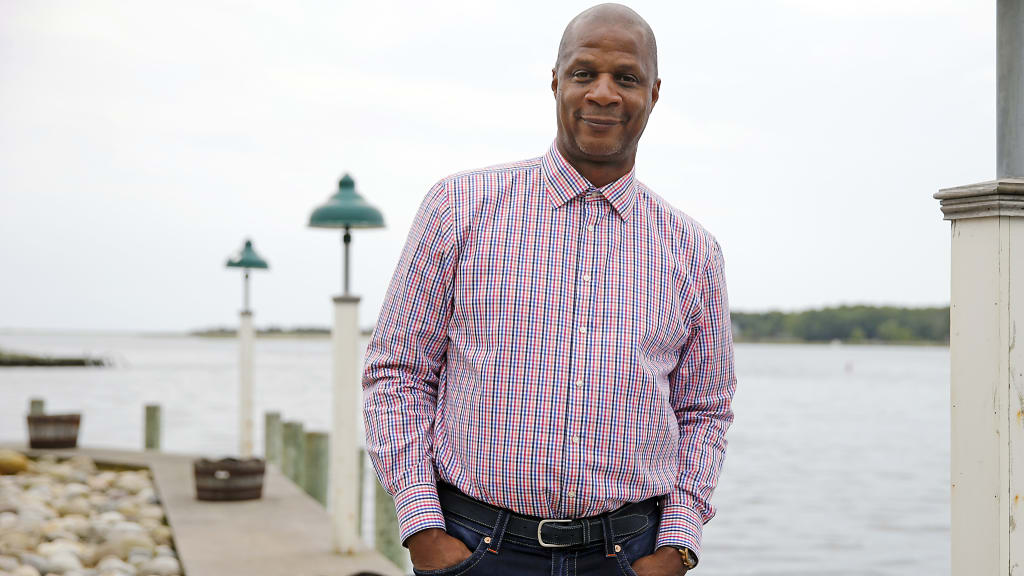

Wearing a pair of jeans and button-down shirt, he makes his way out to the backyard -- a huge expanse of perfectly manicured green grass -- and sits down on a wooden lounge chair facing Moriches Bay. Luppo is not far behind.

With beautiful scenery in front of him, Strawberry is completely open about the not-so-beautiful years that are now behind him.

Strawberry's problems began when he was a child living with an abusive father.

"We don't all have good homes behind closed doors," Strawberry said. "My father was physically and emotionally abusive. One night, he brought a shotgun home and said he was going to kill our whole family. That's when we stood up to him and finally got him out of the house for good."

But Strawberry had already turned to drugs and alcohol by then.

"I started drinking and smoking marijuana when I was 13 years old," he said. "I was already in trouble coming out of junior high school. I was smoking a couple joints before I got to school, and there were times when I wouldn't even go to class. I would go into the bathrooms and start a fire because I was high and I didn't want to go to class. I continued to drink and use drugs when I got to high school, even though I was playing sports."

A few weeks shy of his high school graduation, Strawberry was selected by the New York Mets with the first overall pick of the 1980 Draft, and he would soon report to the team's rookie league club in rural Kingsport, Tenn. There, he used the same vices to cope with being away from home for the first time.

"At that time, I just drank more and smoked more than when I was in high school," he said. "People don't realize that drinking and smoking marijuana are going to lead to other drugs, but they do. Eventually, marijuana and alcohol are going to stop working, and you need to get to a different place."

For Strawberry, the jump from marijuana and alcohol to drugs with stronger effects came at about the same time he made the leap from the Minors to the Majors. He remembers that on his first road trip with the Mets, veteran teammates offered him cocaine.

"That was part of the Big League lifestyle at that time," Strawberry said. "The drug when I came up was cocaine. I went to the back of the plane and tried it, and I liked it. I fell into the same lifestyle as everyone else, drinking and using cocaine."

Despite the continued substance abuse, Strawberry thrived on the field, especially during the 1980s and 1990 season with the Mets. After taking home the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1983, Strawberry earned the first of eight consecutive All-Star selections in 1984. In 1986, the right fielder hit 27 regular season home runs along with a longball in Game 7 of the World Series that all but clinched the title against the Boston Red Sox.

Yet even as he was succeeding on the diamond, and also raising a family with his first wife, Strawberry could not find happiness.

"Playing baseball wasn't a problem," Strawberry said. "That was easy. I pretended I was happy because I was successful playing baseball, but I was never a real man. I was never a real husband, and I was really never a real good father. I just wanted to do what I wanted. So it was great to accomplish all of those things as a baseball player, but that didn't make me a man."

As the years rolled on, things only got worse for Strawberry off the field. Just before the start of his final season with the Mets, Strawberry -- whose first wife filed for divorce in 1989 -- entered an alcohol rehabilitation program. He would enter treatment two more times during his playing career, once while playing for his hometown Dodgers, and once while with the Giants.

"I enjoyed living the heathen lifestyle," Strawberry said. "I enjoyed the women and the partying, and I didn't want to give it up. When people say they didn't love that lifestyle, they're lying."

Strawberry signed with the San Francisco Giants in 1994, but prior to the next season, he tested positive for cocaine. Citing a clause in Strawberry's contract, the Giants released him.

"When I was finished with the Giants, I didn't care about playing baseball anymore," Strawberry said. "I had enough money at the time. Then, after I went through the whole process of being suspended for 60 days, I started getting calls about possibly coming to play in New York again. The thought of returning to New York to play baseball was the only thing that sparked my interest in ever playing again."

By June 1995, George Steinbrenner signed Strawberry, and what came next was an even more tumultuous time for the 33-year-old than the previous decade. When the Yankees declined to exercise their option on Strawberry's contract after the '95 campaign, the outfielder began the next season with the St. Paul Saints of the independent Northern League.

Steinbrenner, who kept a close eye on Strawberry, again brought him back, purchasing his contract from St. Paul in July 1996. The slugger rewarded The Boss for taking another chance on him. In the regular season, Strawberry hit 11 home runs. He hit three more in the American League Championship Series against Baltimore, helping the Yankees advance to the World Series for the first time since 1981. When that season was all said and done, Strawberry was again a world champion, 10 years after winning it all with the Mets.

After battling injuries for much of 1997, Strawberry, who was married for a second time, hit 24 home runs for the Yankees team that won 114 regular season games in 1998. But before the '98 Yankees could cement their legacy as one of the greatest teams of all time, baseball became an afterthought for Strawberry for a shocking reason.

After inexplicably losing weight for much of the season, Strawberry underwent a series of tests. Much to his surprise, he was diagnosed with colon cancer.

"That changed my perspective on life more than anything else did," Strawberry said. "My mom died at the age of 55 from terminal breast cancer, and there I was in my late 30s going through a similar process. I didn't know if I was going to make it or not."

Two days after the diagnosis, Strawberry underwent successful surgery to remove a tumor in his large intestine, and at the end of October, he joined his teammates in the World Series victory parade.

Strawberry's troubles would soon return. The next April, shortly after finishing his chemotherapy treatments, he was arrested for possession of cocaine and soliciting a prostitute. Another suspension was handed down, but at its conclusion, Steinbrenner again brought the slugger back. Strawberry made the most of the opportunity, hitting two postseason home runs during the Yankees' 1999 championship run.

The 1999 World Series marked Strawberry's final chapter in baseball. In 2000, he relapsed again and was ordered by the court to undergo treatment. During that time, the cancer returned, and Strawberry needed surgery to remove his left kidney. After leaving the treatment center without permission in October, he was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

In 2002, Strawberry finally hit rock bottom. Additional drug violations -- including an episode in which he left a rehab facility and was missing for three days before being found sleeping behind a 7-Eleven convenience store in Florida -- led to an 18-month prison sentence. Strawberry would serve 11 months in the Gainesville Correctional Institution, and after that, his second marriage fell apart.

"When I took the uniform off, I was in the midst of a complete downward spiral of addiction," Strawberry said. "I'll never forget the number I wore in prison, T17169. When I was in jail, I refused chemotherapy because I would have much rather been dead. But God was doing for me what I couldn't do for myself. He wasn't going to let me go.

"God had a purpose and plan for my life," Strawberry continued. "When I look back on that, God always knew that I would fulfill the purpose and plan. I finally came to a place where I was brought to my knees, and I looked up and answered the call. My purpose was to preach and to help others."

Having rehashed so much of his life, Strawberry decides that it's time for a short walk out to a dock over the bay.

As soon as Strawberry gets to the dock, he asks Luppo to come out there with him. When Luppo gets there, Strawberry grabs him by the shirt and pushes him toward the water. The much larger Strawberry never lets go of Luppo, but he successfully lightens the mood, and the two share a laugh.

"You see what I have to deal with?" Luppo said.

Answering God's Call

With a thunderstorm looming, Strawberry and Luppo retreat to the kitchen. The pastor of South Bay Bible Church and his family have delivered several lunch platters, including a large plate of sandwiches, pastries and potato salad.

"Let's dig in," Strawberry said while taking a plate from the marble island and placing two sandwiches on it.

As the rain starts to pour, Strawberry takes a seat at the kitchen table, anxious to discuss what he considers the best part of his life.

A few years after being released from prison, Strawberry, who was cancer free, met his wife, Tracy, at a narcotics anonymous convention in Florida. Although Tracy was clean, Strawberry was still using drugs, but when she convinced him to move from Florida to her hometown outside of St. Louis, Strawberry's life turned around for good.

"I knew she was a wonderful person the minute I met her," Strawberry said. "We started having conversations about life. We talked about the struggles we both had. We started dating, and from there, we moved into our own destiny. It was a process that we had to walk through together."

Strawberry married Tracy in 2006, and the couple made a home near St. Louis. Soon after their wedding, the Strawberrys began a foundation that raised awareness for childhood autism.

In addition to that cause, the couple was busy studying the bible with the hopes of someday starting a ministry.

"We sat for years just doing work back in our church in St. Louis," Strawberry said. "We started from the ground up. We had to build character and integrity. At first, we went to a lot of youth detention centers and spoke to kids. Then, we started traveling and doing ministry together, and all of a sudden people began to realize that we were for real and that we were in it simply to help other people. So many people started to send requests for us to preach at their churches."

In 2007, they both became ordained ministers, and in recent years, he estimates, they have spoken at about 400 locations.

"My life has been a transformation like never before," he said. "I'm still Darryl Strawberry, but I don't wear a Mets or Yankees uniform. I don't talk about baseball. I talk about God. I found the purpose of life, and it's about helping others."

In addition to the Strawberry Ministries, the man who hit 335 home runs in a 17-year Major League career has also lent his name to three drug rehabilitation facilities -- two in Florida and one in Texas.

"When I was approached by my dear friend Ron Dock about a group that wanted to open treatment centers in my name, I wasn't sure about the idea," Strawberry said. "I told him that if I can really help people, I'll do it. But I didn't want to do it just for show. I told him that I would want to be hands-on and be able to make a difference in people's lives."

After living outside of St. Louis for 13 years, the Strawberrys pulled up their roots and moved to Orlando, to be closer to the Darryl Strawberry Recovery Centers in Central Florida.

When Strawberry is not traveling, he's at the centers two to three days a week, sitting in on group therapy sessions and talking to patients for hours at a time.

"I don't have a formal role," Strawberry said. "My job is to wake up and go there to help somebody. I have a desire to be there. I don't have to go there, but I want to."

Strawberry has also repaired his relationships with all six of his children.

"I'm blessed that all the pieces that were broken have been put back together," Strawberry said.

With all of the things that have changed for the better in his life, Strawberry has finally found the sense of happiness that had always eluded him.

"I have a joy that is greater than the one you get from having millions of dollars," Strawberry said. "I didn't find complete wholeness until I came to God."

Spreading His Message

With about two hours until Strawberry will be leaving for the school, he decides to retreat to one of the bedrooms for a nap.

At 3:45, he emerges, wearing a white dress shirt, buttoned to the top, a pair of jeans and a pinstriped sports jacket.

"We need God to help us with the rain," Strawberry said. "We need it to stop before 5 o'clock."

The pastor soon arrives at the house so that Strawberry and the Luppos can follow him to the middle school.

When they leave, Strawberry realizes that the rain has finally stopped.

"God knows what he's doing," Strawberry said with a smile.

After a five-minute drive, Strawberry arrives in a parking lot next to the middle school. While still in the parking lot, Strawberry leads the small group of people with him in a prayer outside the car.

As the clock ticks closer to 5 o'clock, Strawberry, the Luppos and a few people from the church begin to make their way to the other side of the school, where a stage is set up and an audience is waiting.

Moments later, the church's pastor introduces Strawberry, and the former ballplayer takes the stage. He recounts his life as a "liar, a cheater, a womanizer, an alcoholic, a drug addict and a sinner." He recounts how he was saved by the grace of God. "Whatever your issues may be, whatever you may be struggling with, you can get through it and you can be set free," he assured the crowd. And afterward, he tries to reach a man whose sister is desperately trying to rescue him from his own downward spiral.

As Strawberry gets into the car at the end of the night, he's asked about the man he spoke with in the parking lot.

"In those situations, you try to get people to understand that their lives can change," he said. "They're struggling real hard, and most of them don't make it. That's why it's so important to educate young people about the dangers of drugs so that they don't get addicted in the first place. Drugs are the enemy, and the enemy is here. If my message got through to one kid in that audience, this was a very good trip."

Tomorrow, he'll head to New Milford, Conn., where his mission will begin again.