From THE CAPTAIN by David Wright and Anthony DiComo, published on Oct. 13, 2020, by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2020 by David Wright and Anthony DiComo.

As far as I could tell, my “Captain America” nickname was the creation of MLB Network broadcaster Matt Vasgersian, who coined it during our second-round game against Puerto Rico [in the 2013 World Baseball Classic]. It spread rapidly on social media and in newspapers from there; within days, fans were mailing me T‑shirts and other paraphernalia related to the superhero. Back in Port St. Lucie, our PR director Jay Horwitz dressed up in a full-body, royal blue spandex suit, taking photos in front of my locker and telling everyone he was Bucky, Captain America’s sidekick. Some of my teammates took to wearing screenprinted T‑shirts featuring my face and Captain America’s body.

As usual, I was a bit uncomfortable being the center of attention off the field. I never felt like I needed a nickname or a superhero persona or anything like that, so I shrugged off the Captain America thing when people asked me about it. But I did appreciate the fans, whose enthusiasm for the concept rubbed off on me. Captain America always looked pretty cool in comic books and movies, carrying around that iconic red, white and blue shield. Even I could admit the comparison was flattering.

The night Vasgersian coined my nickname coincided with one of the most memorable WBC performances of my career. Having already driven home two runs in the game against Puerto Rico, I stepped into the on‑deck circle in the eighth inning with men on first and second, one out and a 4-1 lead. At that point, pitching coach Ricky Bones came to the mound to make a change.

Ricky had been the Mets’ bullpen coach since 2012, which was another fun example of the familiarity between WBC opponents. On nearly every team, I could count teammates and coaches whom I knew well. Those relationships led to a little more trash-talking than in regular-season games, like when I yelled at Carlos Delgado following my walk-off against Puerto Rico in '09. Playing against friends added extra emotion. So when the new pitcher, Xavier Cedeño, walked [Joe] Mauer, I looked at Ricky and just shook my head. It seemed pretty clear Cedeño was pitching carefully around Mauer to load the bases and get to me. (Ricky later admitted that he liked the matchup better, believing Cedeño could get me out with inside pitches.)

I decided to take it personally.

Cedeño threw me four consecutive curveballs, and on the fourth of them, I hit a towering fly ball to the warning track in right-center to drive home all three runs. Rounding first, I stared into the Puerto Rican dugout and tossed my bat in the general direction of Ricky. It was all in good fun, but after that walk of Mauer, I wasn’t going to let the opportunity to trash-talk pass. For the rest of my career, I brought that game up to him at least once a season, saying decisions like that were why he was a bullpen coach and not a pitching coach.

(Disclaimer: I actually think Ricky is more than qualified to be an excellent pitching coach. But it felt great to make that decision backfire on him, and he will never, ever hear the end of it from me.)

At that point, I was hitting as well as anyone in the tournament, having as much fun as I’d ever had on a baseball field. Most important, we were winning. Thanks to those key victories, the Americans had a real chance to take home the gold.

The only bummer? They were going to have to do it without me.

Before the World Baseball Classic began, I started experiencing some left rib soreness. Initially mild enough to ignore, the pain seemed to worsen with each passing day. One off-night early in the tournament, my fiancée Molly and I went to dinner with Jeff Francoeur and his wife in Arizona. I kept fidgeting in my seat at the restaurant, even standing up during the meal to ease the discomfort I was feeling.

I had ignored plenty of injuries in the past, so this seemed like just another challenge. But as the WBC progressed, the ache grew increasingly worse. At one point, I brought a chiropractor to my hotel room because I thought one of my ribs had popped out of place. I was hoping he could snap the thing back into its proper spot.

Following my five-RBI performance against Puerto Rico, my rib felt sore enough that I had to say something to the Team USA training staff. That set off all sorts of alarms back at Mets camp, where team officials began communicating directly with WBC staffers. As far as injuries go, it didn’t seem like a significant issue, but the twists and turns of baseball activities can really wreak havoc on those little core muscles. The Mets were concerned that, with only three weeks until Opening Day, continuing to play would mean risking my health for the regular season. As much as I loved the WBC, it was a bargain we were all unwilling to make.

Minutes before the start of Team USA’s next game against the Dominican Republic, all parties agreed it was best for me to shut it down. About an hour later, I stood in a noisy tunnel at Marlins Park to relay the decision to the media: My red-hot tournament was finished.

Mets doctors wanted to examine me personally, so I went up to New York for a cortisone shot and an MRI, which revealed a mild left intercostal strain.

Team USA went on without me. The night I left Miami, my teammates lost to the Dominican Republic. The following evening, they lost a rematch with Puerto Rico as I watched from New York. One of my teammates found a blue and red Captain America snapback cap and placed it on a dugout pillar, where it stayed propped up the entire game. I wish it had bestowed a little more fortune on them. Our bid to become the first Team USA to win the World Baseball Classic fell a few games short, and while it was frustrating to watch that unfold from afar, I took comfort in knowing I had done the right thing.

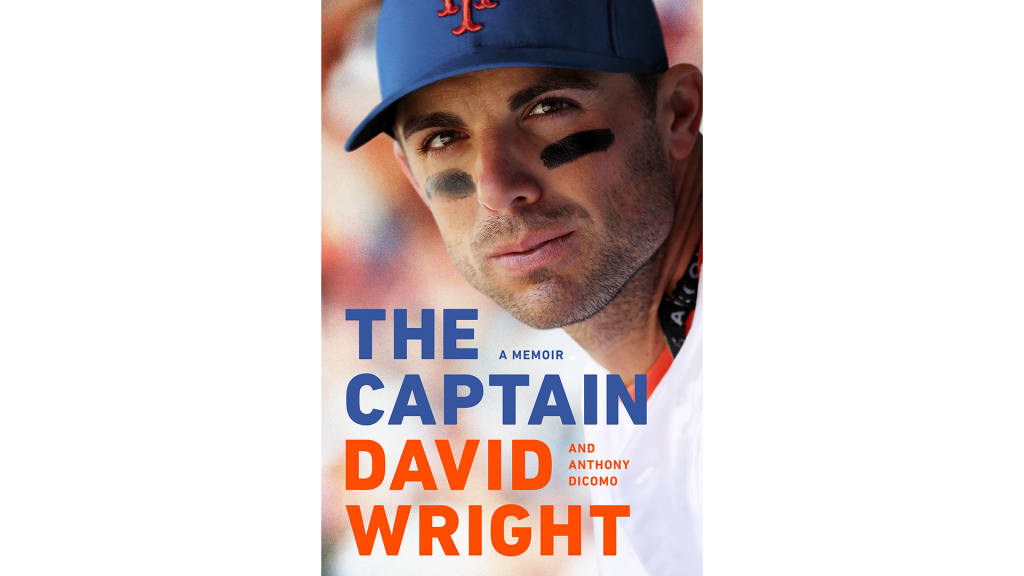

I knew I might never get another chance to win a gold medal. That sucked. But at least a World Series trophy was still very much in play. And as it turned out, something else was in the works. Shortly after my return to Mets camp, Terry Collins called me into his office for an unscheduled meeting including Jeff Wilpon from the Mets’ ownership group, as well as general manager Sandy Alderson and Collins’ entire coaching staff. They wanted to name me the fourth captain in franchise history and the first since John Franco retired in 2004 -- my rookie season.

Although I had heard the whispers earlier in Spring Training, hearing those words out loud floored me. Captains had become increasingly rare in Major League Baseball; at that time, the only ones were [Derek] Jeter of the Yankees and Paul Konerko of the White Sox. The Mets had named only three in their history: Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter, who served as co‑captains, and Franco, whose leadership helped the Mets and New York City heal after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

To be considered in the same light as those guys took my breath away. I thought back to when I was a kid with the Virginia Blasters, when Coach Allan Erbe conducted annual players-only votes to determine our captains. Everyone would write a name or two on a piece of paper, then Erbe would tally up the results and the top two vote-getters would earn the positions for the upcoming season. The two times I received that honor, I felt so proud knowing my teammates thought of me in that way. To have the same opportunity placed before me as an adult, playing for the team I grew up rooting for, was something I did not take lightly.

Which is why I had to say no.

To be clear, I wanted to be the Mets’ captain. Badly. I just didn’t want the title to come from ownership, the front office, or the manager. Like when I was with the Blasters, I wanted the decision to come from my peers or not at all.

To me, captain was not just a ceremonial position. It meant being a leader, a confidant and a trusted authority figure within the clubhouse. It meant setting an example, establishing a culture. Clubhouses are sacred places. I was never going to be some sort of hard-line disciplinarian, but I also wanted the best out of my teammates. If I was going to accept the responsibility of becoming an even more public face of the team, of chastising guys for slacking off or breaking rules -- things I tended to do anyway but which were about to become part of my new job description -- then I needed to make sure those people accepted me as their leader. If I had the title of captain without the respect of the room, I knew my words wouldn’t carry any weight when it came time to fulfill those duties.

Sitting in the manager’s office alongside Jeff, Sandy and Terry, I made it clear the only way I was going to say yes was if my teammates approved the decision.

Locker by locker, I went around the clubhouse and told each of my teammates the story: The Mets wanted to name me captain, but I wasn’t going to accept the role without everyone’s blessing. Because I didn’t want to put anyone in an awkward position, I told them if they were in favor, they should tell Terry or Sandy. If they didn’t want me to be captain, they should voice that opinion, too. If they didn’t feel comfortable saying something directly to management, they could tell a coach or a veteran player instead. The whole idea was that, positive or negative, I’d never know who said what.

Going around the clubhouse, giving that spiel to various players, felt a little strange. Some of them, like Daniel Murphy and Dillon Gee, I had known for years. Others, like Juan Lagares and Wilmer Flores, were rookies without much experience. Still others, like John Buck and LaTroy Hawkins, were longtime big leaguers I had only recently met. It was important for me to talk to each one of them personally, regardless of their stature.

I never did find out what anyone said, but the feedback must have been mostly positive. Less than a week after returning from Port St. Lucie, I was in the trainer’s room, dripping water onto the carpet from the ice wrapped around my strained intercostal, when Collins called a full-team meeting. The whole room broke into applause as he announced the Mets were going to name me captain. As usual, the attention made my stomach roil, but the feeling of having that support was overwhelming. The entire meeting was kind of a blur, as was the press conference to announce the news in Port St. Lucie.

At that point in my career, I was proud of what I had accomplished, both individually and as a teammate. But it all paled compared to this. Being named captain of the Mets was by far the greatest professional honor I had ever, would ever or could ever receive. The title meant my teammates respected me as a person, which was a greater accolade than anything that could go on the back of a baseball card.

The only part of the captaincy that didn’t appeal to me was the idea of putting a "C" on my jersey. I understood the decades-old tradition, but it just wasn’t in my personality to stick out to that extent. My mindset was that a uniform is a uniform for a reason. Even though I might have been a team leader, that was always going to manifest itself behind the scenes. Thankfully, everyone understood, so it was an easy call to leave the "C" off my jersey.

In that and other ways, not much actually changed after the Mets named me captain. I didn’t act differently. I might have enjoyed a little confidence boost knowing people were more likely to listen when I talked, but I wasn’t much of a rah-rah guy or a team-speech guy to begin with. My goal was always to lead by example. When I did feel the need to speak up, I tried to do so behind the scenes, in private moments, with discretion. If guys took what I had to say more seriously because I was the captain, all the better.

In subtle ways, I do think becoming captain made me a better teammate and person. Had injuries not interfered, it probably would have made me a better player, too. The title held me accountable for a lot of things I did both on and off the field, almost as if I had this new spotlight on myself. I knew my teammates were trying to emulate me, so I redoubled my efforts to do everything the right way, from my interactions with the media to my effort level on the field.

Don’t get me wrong, this wasn’t a new concept for me. It’s just that, as captain, the last thing I wanted to do was have a moment of selfishness or weakness, to give away an at‑bat or space out on defense. Rather than spend a single second focusing on, say, how many home runs I had, I focused instead on my preparation and training.

Being captain held me to a higher standard as a player, teammate and leader. I took that responsibility and honor with grave seriousness for the rest of my career.