There’s nothing like a great baseball story. But baseball has been around a long time, and in some cases, it can be hard to tell whether those stories are too good to be true. Which is why MLB Mythbusters is here to help -- we'll be diving into some of the game's greatest legends, trying to separate fact from fiction.

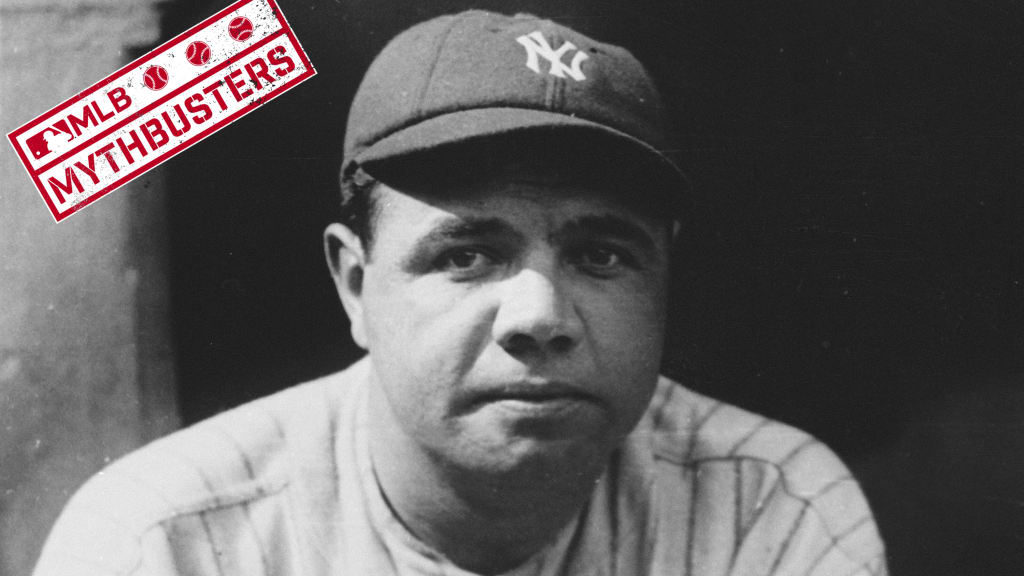

First up: On the Babe's 125th birthday, we investigate arguably the most famous home run in baseball history.

The myth: Did Babe Ruth really call his home run off Charlie Root in Game 3 of the 1932 World Series?

The context: Oct. 1, 1932. Wrigley Field. The Yankees, having cruised to wins in Games 1 and 2 at home, head to Chicago looking to capture their third World Series title in the last six years.

Cubs fans, though, have other ideas. Their team hasn't won a title in 25 years, and they are ready, ragging on Ruth, Gehrig, and the rest of New York's cavalcade of stars from pretty much the moment they get off the bus -- booing, hissing, throwing the occasional fruit, whatever it takes. (Ruth allegedly got so fed up during batting practice that, after launching several homers to end his session, he walked over to Chicago's dugout, guaranteed a sweep and then taunted some autograph seekers on his way off the field: "Did you hear what I told them? I told them that they ain’t going back to New York." Again, this is hours before first pitch.)

Once the game starts, all bets are off. Cubs players are even getting in on the act now, perching on the top step of the dugout and talking trash at every Yankee who steps up to the plate -- "callin’ me big belly and balloon-head," Ruth would later recall. The Babe responds with a towering three-run blast in the top of the first, then takes the field for the bottom half and gets plunked by a lemon from the left-field bleachers.

With two runs in the third and one more in the fourth, the Cubs have clawed their way back. Wrigley's heckling has built to a roar. Ruth steps to the plate in the top of the fifth with the game tied at four ... and has shutting up the entire city of Chicago on his mind.

The evidence: What happened next is one of the most hotly debated topics in the history of American sports, so let's begin with what we know.

- We know that Ruth, even in decline at age 37 (1932 marked the first time in seven years that he didn't lead the Majors in home runs) was still arguably the best baseball player on the planet. He slashed .341/.489/.661 during the regular season, good for a truly bonkers 201 OPS+.

- We know that he was really, really feeling it that day. His batting practice was, by all accounts, jaw-dropping: “[He's] on fire,” Gehrig told the Tribune after taking it in. "He ought to hit one today; maybe a couple.” Then he went out and went yard in his first at-bat.

- We know that he was fired up -- Chicago was giving it to him from every direction, from the stands to the dugout, and he was giving it right back.

- We know that he was, well, Babe Ruth: the living legend, the movie star, the consummate showman, the man who once mailed a sick child a baseball with the message "I'll knock a homer for you on Wednesday," then went out and hit three.

- And we know that, during his at-bat in the top of the fifth, he got into it with some Cubs players. He took strike one, exchanged some words and held up one finger to Chicago's dugout. He took two balls, then another strike. After strike two, he pointed with his right hand -- to starting pitcher Charlie Root, or to the dugout, or out to the flagpole beyond center-field -- and on the very next pitch, he hit one onto Sheffield Avenue to put the Yankees ahead for good.

But just what was that gesture, and what did it mean?

The argument for: According to Joe Williams, a columnist for Scripps-Howard, the answer was obvious: Ruth had pointed to dead center field and called his home run. The story ran in the next day's New York World-Telegram, complete with a booming headline: “Ruth Calls Shot As He Puts Home Run No. 2 In Side Pocket.”

And, in the days before television, that was enough. The whole thing just felt true: This was quite possibly the biggest celebrity in the country, a man larger than life; of course Babe Ruth called a home run in a hostile environment in Game 3 of the World Series, because he was Babe freaking Ruth. The legend soon spread like wildfire, with plenty of eyewitness to back it up over the years -- from teammates like Lefty Gomez to Wrigley PA announcer Pat Pieper to even Supreme Court Justice and diehard Cubs fan John Paul Stevens, who attended the game as a kid and swore that Ruth called it.

"Ruth did point to the center-field scoreboard," Stevens recalled. "And he did hit the ball out of the park after he pointed with his bat. So it really happened."

The argument against: So, what's the problem? Well, there are a few. For starters, of all the reporters at Wrigley that day, the majority didn't make any mention of it: not Red Smith; not Shirley Povich; not even Grantland Rice, a man who never missed an opportunity to be as dramatic as humanly possible. The Chicago Tribune managed to have two differing accounts in the same issue: Westbrook Pegler claimed that Ruth "laughed derisively and gestured at him, 'Wait, Mugg, I'm going to hit one out of the yard,'" while Irving Vaughan maintained that the Babe was simply counting how many strikes were on him. What's more likely? That half of such a collection of sportswriting talent simply missed the biggest athlete in the country talk junk at the plate in the middle of the World Series, or some scribes (including, as it happens, those from Ruth's hometown) got a little overexcited?

Not even the man himself seemed particularly convinced. Ruth's initial response was more muted than you'd expect from someone who'd just called their shot in the World Series -- immediately after the game, he demurred, implying that he'd just been talking some trash in between pitches. An interview he gave early in 1933 seems awfully definitive:

Hell no. It isn't a fact. Only a damned fool would have done a thing like that [...] Then there was that second strike, and they let me have it again. So I held up that finger again, and I said I still had one left. Now kid, you know damn well I wasn't pointing anywhere. If I had done that, Root would have stuck the ball in my ear. I never knew anybody who could tell you ahead of time where he was going to hit a baseball. When I get to be that kind of fool, they'll put me in the booby hatch.

It wasn't til the called shot became The Called Shot that he doubled down, telling Chicago Daily News reporter John Carmichael "nobody but a blankety-blank fool would-a done what I did that day." And even then, his story changed constantly -- in one interview he picked out a specific spot in the bleachers, in the next he was merely pointing to the outfield, in the next he dreamt about the homer the night before. Eventually it became nearly impossible to get a straight answer out of him, as if he relished the ambiguity: While filming "Pride of the Yankees" together several years later, Root claims that the Babe acknowledged the story wasn't true, but added, "made for a [heck] of a story, didn't it?" (For what it's worth, just about every Cubs player, from Root to catcher Gabby Hartnett, went to their graves vehemently denying that it was true.)

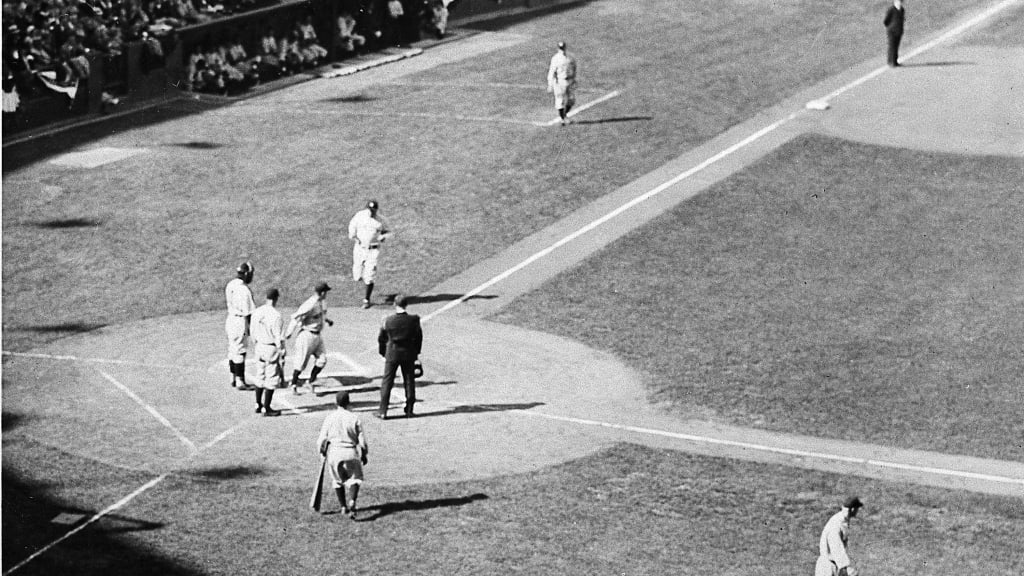

Which brings us to the final item of evidence: the video. Inventor Harold Warp only went to one baseball game in his life, but it just so happened to be Game 3, and he just so happened to record some of it for posterity -- including Ruth's infamous at-bat. In 1999, his family unearthed the footage and shared it with the world ... and, well, see for yourself:

Definitive? Hardly, but it sure does seem as though Ruth's gesturing -- including those two fingers held up to indicate two strikes -- is directed at the third-base dugout, rather than out to center field.

So, after all that, where do we stand? Did Babe Ruth call his shot, or didn't he?

The verdict: He did, just maybe not in the way we usually imagine it. It seems safe to say that, if Ruth really had pointed his bat out to dead center field and then immediately parked a baseball there, the contemporaneous reporting (not to mention the Babe's ensuing response) would've been more consistent; it's awfully hard to believe that anyone in the press box would've missed it, and that Ruth would've been so coy until later on.

But we know that there was plenty of jawing back and forth, everyone seems to agree that Ruth was counting strikes, and the video pretty clearly shows that something was about to happen on that next pitch. So the most likely answer is a bit of both: No, Ruth didn't precisely predict his homer, but he did stride up to the plate, fans and opponents jeering at him, and tell the world "hey, watch this." Which is still 1) sort of calling his shot and 2) most important, an absolutely incredible flex, the sort of thing that kids will try to emulate for decades afterward. Because, like any good myth, believing in the story is way more fun.