On a chilly February morning in Tampa, Fla., Yankees infielder DJ LeMahieu stood on the top step of an empty dugout at George M. Steinbrenner Field and pondered the upcoming 2020 season. The three-time All-Star paused for a moment and thought about his first year in New York, when the Yankees overcame a tidal wave of injuries to win the American League East division but fell short in the 2019 American League Championship Series against Houston.

“I think we have a big chip on our shoulder, collectively as a group,” LeMahieu said. “I expect this season not to go smoothly, but I expect us to be standing at the end.”

He wasn’t referring to an as-yet-unforeseen global pandemic, but LeMahieu’s prediction that 2020 would not go smoothly was beyond prescient. Fast forward to Aug. 5, when the Yankees traveled to Philadelphia for a doubleheader. Both games were slated to go seven innings. Tropical Storm Isaias had forced the postponement of the Aug. 4 game at Yankee Stadium, so for Game 1, the Yankees were the “home” team but wore their road grays. Phillies manager Joe Girardi penciled in a designated hitter, and the public-address system at Citizens Bank Park blasted canned crowd noise and walk-up music that favored the Yankees. It was the 10th game of the season for the Yanks, the fifth for the Phils. Cardboard cutouts of fans populated the lower seating bowl. One hundred miles away, Rickie Ricardo -- filling in for an under-the-weather John Sterling -- and Suzyn Waldman called the game on radio by watching it on monitors in the WFAN broadcast booth at an otherwise vacant Yankee Stadium.

As bizarre as baseball in the time of coronavirus has been, there were also comforting signs of familiarity in that twin bill opener. LeMahieu led off the bottom of the first against right-hander Zack Wheeler and fell behind, 1-2, then battled back and poked Wheeler’s sixth offering into right field.

“Stop me when you’ve heard this one …” a masked Marly Rivera -- one of the few actual humans allowed to witness the game in person -- tweeted from the press box in Philly while on assignment for ESPN. “DJ LeMahieu with a leadoff hit to RF with two strikes.”

“‘The Machine’ continues to just chug along,” YES announcer Michael Kay said from Yankee Stadium.

It was the start of a 3-for-3 day for LeMahieu -- his fifth multihit performance in seven games -- that raised his average to .459. Even though it was early in the season, the hot start was impossible to ignore, especially considering LeMahieu had tested positive for COVID-19 just a month earlier and missed the July 23 opener as he worked himself back into game shape. Once he was cleared to return, LeMahieu joined his teammates and noticed the same hunger and attitude that existed in Tampa before the shutdown.

“Being around the guys,” he said, “I can see a lot of positivity, a lot of optimism, a lot of excitement for the season.”

The Yankees share one goal -- to win the World Series -- and LeMahieu, despite suffering a sprained left thumb in August, will continue to play a prominent role in that pursuit. But there is more to LeMahieu than meets the eye, and while fans in New York have fallen in love with “The Machine” for his MVP-caliber play on the field, they haven’t had much opportunity to get to know the tight-lipped 32-year-old.

Until now.

***

There are three things that, in case you haven’t noticed already, everyone knows about DJ LeMahieu:

He’s really quiet.

He’s super nice.

He’s really not a big talker.

Woody Saylor, a retired postal worker from Northeast Pennsylvania, has been manning the door to the Yankees’ clubhouse during Spring Training for the past 16 years. Without fail, when LeMahieu arrives for work each day, he gives Saylor a warm greeting.

And not a whole lot more.

“He doesn’t say much,” Saylor says. “But he’s one of the nicest guys you’ll meet.”

An executive member of the Yankees’ team security detail concurs, adding, “I’d take 25 guys like him on our team.”

The unassuming LeMahieu is so adept at flying under the radar that, even after a full season in New York, many still were unsure of his back story.

LeMahieu? Isn’t he Canadian?

I thought he’s from Louisiana.

Although he won a national championship with LSU in 2009, LeMahieu spent just two years of his life in Baton Rouge. And no, he isn’t Canadian, although his mother is. And she is a big reason why LeMahieu, now in his 10th big league season, is one of the game’s most humble stars.

David John LeMahieu was born on July 13, 1988, in Visalia, Calif., the only child of Joan and Tom LeMahieu. Tom played college baseball at a small Christian college in Sioux Center, Iowa, called Dordt College (renamed Dordt University in 2019), where on April 9, 1977, he hit for the cycle against Yankton. From the beginning, he nurtured his son’s love for baseball, taking him to Spring Training games in Arizona when DJ was just a toddler. Tom and his son talk just about every day, with “probably 75 percent” of the conversation hovering around baseball.

“My dad’s still kind of my mentor,” LeMahieu says. “He’s had just a huge impact on my career, for sure.”

When DJ was 7, the LeMahieu family moved from California to Las Vegas. A year later, they packed up for Madison, Wis., where they stayed for five years until they moved to Bloomfield Hills, Mich., a suburb of Detroit. LeMahieu enrolled at Brother Rice High School, a private all-boys Catholic school with a nationally renowned baseball program. But the family’s moves were not part of some grand plan to groom their son for the big leagues. A review of Joan’s curriculum vitae makes that plain to see.

Joan LeMahieu’s mother grew up on a small farm in rural British Columbia, the daughter of hard-working Dutch immigrants who lived through World War II. Joan’s mother dropped out of school in the Netherlands after seventh grade, but she encouraged her daughters to set their sights on attending college. Joan heeded her mother’s words and, after working on the family farm from a young age and working at a bank to pay her own way at Dordt, began a highly successful career in venue management, event development and hospitality. She specialized in the planning and opening of large venues such as stadiums, convention centers and multipurpose centers.

The Detroit Lions were getting set to open Ford Field around the start of the millennium and needed someone to spearhead the project. They were impressed by what Joan had accomplished at Madison’s Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center and hired her as general manager of the 65,000-seat stadium. The opening of Ford Field in 2002 was lauded as a rousing success, and The Detroit News named Joan LeMahieu one of its Business Women of the Year.

It must have been pretty cool for a teenage boy to have a mom running Ford Field, scoring backstage passes to WrestleMania and eating all the free hot dogs he wanted … right?

“She put me to work,” LeMahieu counters. “I was always, like, working in the warehouse and stuff like that.”

LeMahieu understood from an early age that his compassionate yet hard-working parents would always do what was best for the family. Nearly two decades later, those values and lessons remain part of LeMahieu’s DNA, as his Yankees teammates marvel at his work ethic and dedication to his craft.

“I just try to learn from DJ,” says fellow All-Star Gleyber Torres, who along with LeMahieu forms one of the most dynamic middle-infield combos in baseball. “He was so great last year. Every time he would go to the cage, I would try to follow him and try to learn everything about his routine. It’s amazing what he does every time he steps to the plate.”

***

Sophia Rose Ebbing turns 5 this year, and whenever she watches a Yankees game with her dad, Pat, and sees LeMahieu on TV, she’ll get excited and say, “Uncle Too-Day!”

Pat and DJ have been best friends going back to their days at Brother Rice, where, as a freshman, LeMahieu supplanted an assistant coach’s younger brother as the team’s starting shortstop, and as a junior and senior, became Michigan’s first and only two-time Gatorade Player of the Year. (Even Kalamazoo Central’s Derek Jeter only won the award as a senior.)

LeMahieu’s athletic accolades and overall talent -- he also played varsity basketball, and friends say he could have played quarterback if he went out for football -- were evident, but his work ethic remains legendary, to the point that his buddies are almost reticent to rehash it.

“I know it’s the corny thing that’s in every story, but he just worked and worked and worked,” says longtime friend Brad Galli, a sports anchor for ABC’s Detroit affiliate, WXYZ. “During football season, we would do these agility drills at 6 a.m., and DJ would be in there before us hitting. He hit like crazy. We’d be eating breakfast in the cafeteria, and he’d be hitting. All the time. All the time.”

Galli was among the group of friends who went to Cincinnati’s Great American Ball Park in 2015 to show their support for LeMahieu when he made his first All-Star team, and their paths sometimes cross in a professional setting. While covering the Tigers’ Spring Training in Florida for WXYZ, Galli met up with LeMahieu in Tampa.

“I came back and said, ‘He’s the same guy,’” Galli says. “Sure, we all evolve, we all grow in different ways, but who he is at his core is always the same. He got to Spring Training super early on the first day. He likes to stay late. That work ethic was always there.”

So was the humility. Ebbing, the best man when LeMahieu married his college sweetheart, Jordan, in 2014, describes him as “one of the most quiet and humble guys you’ll ever meet. He’s just a bring-your-lunch-pail-to-work kind of guy, kind of blue collar.” Then as now, LeMahieu was a fierce competitor for whom no situation was too big, whose words carried much weight as a result of being dispensed so infrequently.

But Ebbing also notes some of the quirks and personality traits that have remained unchanged over the years. “Ultra-loyal” to his roots, LeMahieu lives in Birmingham, just a few miles away from Brother Rice. He’s a Red Wings season-ticket holder, rarely missing a game at Little Caesars Arena during baseball’s offseason. He loves playing cards with his friends -- “For a multimillionaire, he’s one of the most frugal poker players you’ll ever meet. And then the guy just doesn’t make a mistake,” Ebbing says with a laugh -- and he’s a chess wizard, once defeating Ebbing in four moves.

Far from some robot programmed just to play baseball, “The Machine” also has a huge heart.

“What most people don’t know about Deej is that he’s one of the most caring people,” Ebbing says. “My daughter is autistic and calls him ‘Uncle Too-Day’ because it sounds like DJ. DJ’s just really good with her because he’s soft-spoken, he’s not demonstrative and he’s kind of like a gentle giant. It’s been pretty neat as a best friend seeing him become almost like an uncle to my daughter.”

***

Leaning on the railing of the home dugout at GMS Field, reflecting on his journey to this point, LeMahieu does not take for granted the fact that he has a legitimate chance to win a World Series with the New York Yankees this year. It was right here a decade ago, while playing in the Florida State League, with some of his games played on the very field in front of him, that LeMahieu “wasn’t sure if I was going to be cut out for baseball.

“But I feel like, at the same time, that season, more than any other season, is what made me who I am.”

LeMahieu’s memory is a little fuzzy on the date, but his recall of the batting average figure is exact: .220. He remembers it being around the All-Star break, but in actuality it was just a month into the 2010 season -- his first full year as a pro after being taken by the Cubs in the second round of the 2009 Draft. LeMahieu was batting .220 with a paltry .229 slugging percentage, and he couldn’t help but wonder what his college buddies back in Baton Rouge were doing.

One year earlier, LeMahieu and the Tigers had stormed through the 2009 College World Series. They advanced to the best-of-three finals against Texas at Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, Nebraska, where LeMahieu rose to the occasion. His seventh-inning homer in the series opener had cut the Longhorns’ lead, but LSU still trailed in the ninth, 6-4, and was down to its final out when LeMahieu stepped to the plate and ripped a game-tying double into the left-field corner. In the 11th, LeMahieu led off with a walk against Brandon Workman, stole second with two outs, advanced to third when the catcher’s throw went into center field, then scored the go-ahead run on a Mikie Mahtook single. The Tigers won, 7-6.

“That was the most courageous, never-say-die resolve that I’ve ever seen from one of my teams in 27 years of coaching,” LSU head coach Paul Mainieri said after the game.

Two nights later, the Tigers were national champions, and the sophomore LeMahieu was named to the All-Tournament Team.

The following May, LeMahieu looked down at his Daytona Cubs uniform and wondered if he had made a mistake. He knew Rosenblatt was set to host its final College World Series that summer and that his former Tigers teammates would be making a run at another crown. Yet here he was, riding buses around the Florida State League and wondering where the hits had gone. His coach inspected his bats and confirmed that they still had barrels. His dad encouraged him to work through it, to keep his head up.

Looking at the back of LeMahieu’s baseball card, those struggles seem like an apparition. He finished second on the 2010 Daytona Cubs in batting average (.314), RBIs (73), runs (63) and stolen bases (15), and he led the team with 174 hits -- 49 more than any other player on the team.

As always, those phone conversations with Tom were essential.

“He’s just always super positive; that’s why I like talking to him,” LeMahieu says. “That was one of those times where I just had to really dig deep and grind. I definitely had solid coaches that season that were believing in me and pushing me. And then leaning on my dad, it was just a good combo of people around me to kind of get through that.”

One year later, on May 30, 2011, at Wrigley Field in Chicago, LeMahieu made his big league debut, pinch-hitting for a pitcher in the eighth inning and grounding into a double play. He would have just 60 at-bats in a Cubs uniform.

***

There’s something else everyone must know about DJ LeMahieu, something more readily apparent. A couple things, actually.

He’s good at baseball.

He rarely shows emotion on the field.

He’s, like, really good at baseball.

In an effort to clear a logjam of middle infielders, Chicago traded LeMahieu to Colorado on Dec. 8, 2011, and over the next seven seasons, he established himself as one of the National League’s premier second basemen. A free agent after the 2018 season, he signed a two-year deal with the Yankees, and his first season in the Big Apple ended with the biggest hit of his career.

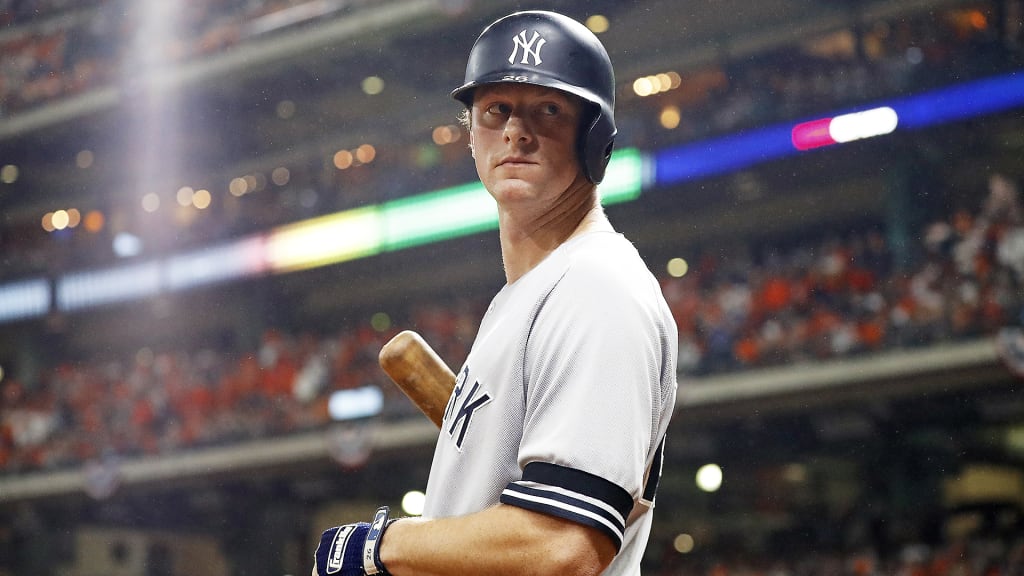

It was Game 6 of the 2019 ALCS at Houston’s Minute Maid Park. The Yankees trailed, 4-2, and were two outs away from going home for the winter. After Gio Urshela singled to lead off the ninth and Brett Gardner struck out, LeMahieu stepped in against Astros closer Roberto Osuna.

It was LeMahieu’s third straight trip to the postseason, his batting average having climbed with each ensuing series. But nothing in his past could fully prepare him for a moment like this.

“The postseason is what you play for, but you don’t get a chance to play there very often,” LeMahieu says. “It’s like, when you’re in the minors, it’s hard to prepare for the big leagues, and in the big leagues, it’s hard to prepare for the playoffs because you just don’t play those type of games every day. But the more I play, the more comfortable I get, the more excited I am for them.”

Any excitement was undetectable to the naked eye as he faced Osuna. In the batter’s box, after falling behind 1-2, LeMahieu had the same look on his face that he wore on Yankees photo day in Tampa this February when a photographer asked him, “What do I have to do to get you to smile?” A stone-faced stare masked whatever LeMahieu might have felt internally as he took ball two, fouled off Osuna’s next four offerings, then took another ball to make the count full.

“Knowing we were down to our last couple ABs potentially, I just didn’t want to get out,” he says. “I was just focused; I was determined. It was one of the more locked-in at-bats I’ve had. We had a guy on first, and I just wanted to keep it going and just find a way.

“And then the homer just happened.”

Ever since he was a kid, LeMahieu’s natural tendency has been to hit the ball the opposite way, to right field and right-center.

“I guess I just had a slow bat,” he quips, which is as close as LeMahieu comes to cracking a joke.

As a Major Leaguer, he says it’s “a balancing act between trying to force my swing to hit the ball the other way and just letting it happen,” but it’s still very much the same swing path that it has always been. And when it connects flush with a pitch over the heart of the plate, like it did with Osuna’s 94 mph cutter, it can do serious damage.

LeMahieu sent Osuna’s 10th offering of the five-and-a-half-minute-long at-bat over the glove of a leaping George Springer and into the right-field seats, tying the game and extending the Yankees’ season, albeit temporarily. Less than 20 minutes later, closer Aroldis Chapman -- who had never allowed a homer in 13 previous postseason appearances with the Yankees -- served up a walk-off longball on an 84 mph slider to José Altuve.

“That could have gone down as one of the all-time great home runs in Yankees postseason history,” says Ebbing, who chucked his hat across a Michigan barroom in celebration when his buddy went deep.

Although it became something of a footnote, the game-tying shot in the top of the ninth was quintessential LeMahieu. He doesn’t have a huge problem with guys who celebrate big moments on the field, but LeMahieu dancing around the base paths or pounding his chest? Inconceivable. He gave a single clap after the ball cleared the wall, never cracking a smile or breaking stride as he briskly circled the bags.

“I guess I’m just not that emotional of a person, and I’m not out there trying to fake anything, so, I’m just being who I am and trying to win baseball games, and I guess that’s just the best way I know how,” he says. “Some guys, they want to feel the energy and get emotional. It’s not like I think you have to be one way or the other. I like guys who are who they are.”

The Yankees love who LeMahieu is, and they can’t wait to see what he does down the stretch this season. He led the team in WAR and provided much-needed versatility around the infield in 2019, and although Yankees manager Aaron Boone has played LeMahieu more regularly at second base in 2020, the skipper can take comfort in knowing all that “The Machine” is capable of. Asked during Spring Training if he’d sign up for a similar season to last year, when LeMahieu’s .327 batting average was the highest by a Yankees player in a decade, Boone didn’t hesitate.

“Uh, yeah, I’d take a repeat.”

LeMahieu downplays the work it took to get to this point.

“Baseball was always my love,” he says. “I still don’t think baseball’s really a job. I just enjoy it. So when people say, ‘You’re a hard worker,’ I just think I’m having fun playing baseball.” But it’s clear that he’s ready to keep pushing even harder to reach that ultimate goal.

“I think this is a special group. This team is more than talented. There’s a special thing here, and that’s going to really help us in this weird 60-game year.”