This article was first published in 2022 on the 30th anniversary of the "Homer at the Bat" episode of The Simpsons.

Thirty-two years ago on Tuesday, an all-time sports miracle happened, one that embiggened the entire history of competitive athletics.

As told in the legendary "Homer at the Bat" episode of The Simpsons, which aired on Feb. 20, 1992, the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant team went from a miserable 2-28 year in ‘91 (which was, somehow, their best season to that point) to an undefeated 30-0 regular season in ‘92, thanks primarily to a homemade bat made magic by lightning. It is the greatest turnaround in sports history.

Even so, owner-manager C. Montgomery Burns remained unsatisfied by his team's success. With the one-game championship against rival Shelbyville looming, Burns spent lavishly to import nine All-Stars in an attempt to guarantee himself a title. He got the victory he desired, but it hardly went as planned, because eight of his nine ringers were unable to actually participate, felled by eight separate misfortunes in the hours before the game.

Still, Springfield won anyway, thanks to nine home runs from Darryl Strawberry before a walk-off hit-by-pitch to break a 43-43 tie from pinch-hitter Homer Simpson, one of the rarest ways to end a game.

Flags fly forever, as they say, even if that flag is a hastily-hung banner partially obscured by the ghostly visage of an unstuck-in-time Ozzie Smith.

But 30 years on, it feels like something is missing. We never did get to see that collection of nine All-Stars on the field at the same time. We never did get to see what the combined might of the ringers would do to Shelbyville, or Fort Springfield, or even North Haverbrook.

We’ll never know, of course. But maybe there’s a more interesting question. What would they have done to the Major Leagues of the time? How good were the nine All-Stars selected in 24 hours by general manager Waylon Smithers, after apparently scouring the American League, the National League and the Negro Leagues, a surprisingly progressive (if woefully past due) order given by the infamously crusty – but not Krusty – Burns?

What we’re trying to get to is this: If not for arguments over British prime ministers, incompetent hypnotists, illnesses tragic and otherwise, the solving of hundreds of open New York City homicides, and all the rest, just how good would Burns’ team of ringers be together, in real life, against the real-life Major Leaguers of 1992? Would they suffer from the lack of Homer’s mighty wallops? On the other hand, might team doctor Nick Rivera’s degree from Hollywood Upstairs Medical College render six months of health impossible anyway? Could they even make road trips via Burns' preferred travel method of auto-gyro?

Fair questions, all. So how are we going to do this? Two methods, really. We’ll do it the math way (estimated WAR totals), and then we’ll do it the fun way (MLB The Show simulations). Using these two methods, we'll examine a trio of scenarios based on how Ol' Monty Burns decides to fill out the rest of his roster.

But first, we have some questions.

* * *

“And the next man wants to hit the ball too. And there he goes off in that direction. And everyone is happy.” – Marge Simpson, while attempting softball play-by-play

There’s an immediate problem in trying to figure this question out. A few of them, really, not including the “is wildly overthinking a 30-year-old cartoon episode the best use of your time” concern that is slowly growing in the back of our minds.

The first issue is that there’s only nine Major Leaguers here. That might be fine in the construct of a single game, but even Roger Clemens needs a few other arms in the rotation over the course of a season. (Though we have a sneaking suspicion that Moe Szyslak might be a surprisingly good junkballer.) Mike Scioscia may have enjoyed running the solid contaminate encapsulator, but over 162 games, he’d probably have enjoyed having a second catcher around even more. We’re going to need to fill out this roster.

But even that raises more questions. Should that second catcher be a perfectly cromulent 1991-'92 big league backstop like, say, Ron Karkovice or Benito Santiago? Or is it more along the lines of … Lenny and/or Carl? We’re going to have to account for that.

The second issue is that while these players all had good-to-all-time-great careers, that’s not exactly what they were in the winter of 1991-’92, which was not actually a good period for many of them. Don Mattingly and his sideburns, for example, was one of the biggest stars in the game from 1984 through ‘89, posting a .902 OPS with six consecutive All-Star appearances. But the end of the 1980s marked the end of his peak, as a string of back injuries limited him to a mere .643 OPS in 1990 and a .738 across 1991-’92. Sax had his final good season in 1991, and was below-average in parts of three more seasons after that. Scioscia's poor 1992 brought his career to an end. A back injury limited Strawberry to 43 games and just five homers. Even Boggs managed to squeeze a lousy 1992 in the midst of a Hall of Fame run of great years.

On the other end of the spectrum, at the time the episode aired, Ken Griffey Jr. was entering his age-22 season and had hit only 60 of his 630 career home runs. We’re not taking careers, we’re taking snapshots at the time, so we’re not taking 1985 Mattingly, when he won the MVP. We’re not taking 1997 Griffey, when he won MVP. We’re in the world of 1992, where these very good players probably weren’t the actual best players. (The producers reportedly approached and were rebuffed by Carlton Fisk, Rickey Henderson, Nolan Ryan and Ryne Sandberg.). So there’s that, too. We'll stick with the players we've got, and take a weighted three-year average of 1990-’92 WAR for each.

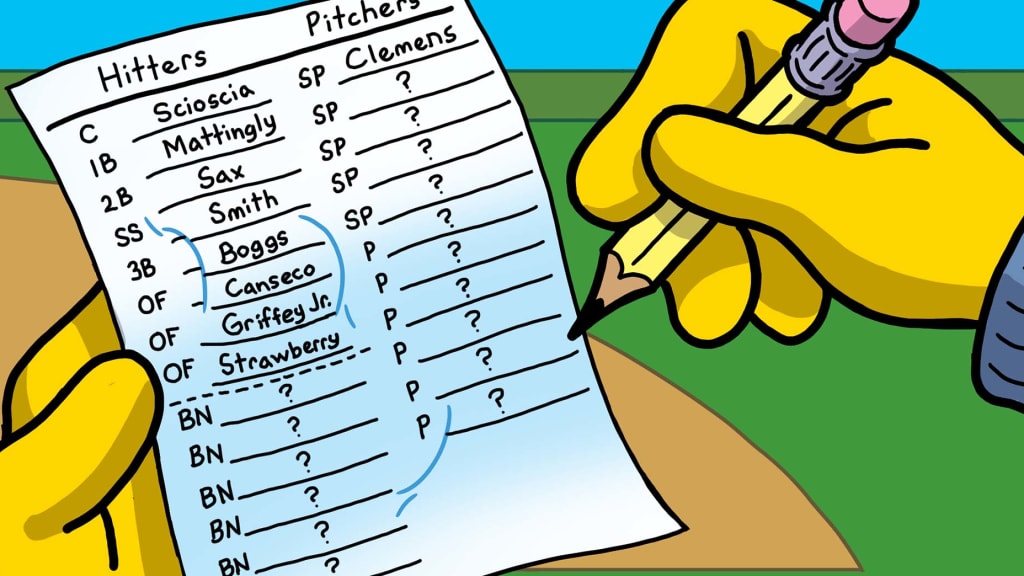

There’s also the question of how much a manager matters. For all the brilliance involved in sending in the “hit a home run” sign to Strawberry, Burns also pinch-hit for his greatest star – who, again, had already hit nine home runs – in the name of gaining a minor platoon advantage. He might think it’s what smart managers do to win ballgames, but the percentages aren’t exactly in his favor. There’s also the minor factor of giving indecipherable signs, somewhat outdated training methods and writing out an inefficient lineup that had Sax hitting in the top two with Griffey Jr. down in sixth.

Still, these are minor inconveniences compared to things like having a right fielder who has been dead for 130 years, as was the original plan. (Burns, it turns out, may not have been very good at this.) Most teams of 1992 would have jumped at the chance to have a core comprised of these nine stars. Right?

* * *

“Are you better than me?”

“Well, I've never met you, but, yes.” – Darryl Strawberry giving an accurate self-scouting report to Homer Simpson.

To fill out the roster, Burns needs 16 players, and let’s not overthink injuries, trades and callups here, even though obviously that would factor into real life. (This is not real life. We're also not going to parse the difference between softball and baseball here, though it's possible the baseball is made out of Secretariat.)

Your first thought is likely: Well, just fill out the roster with the other employees of the power plant, the Homers and Lennys and Carls who were already there. Much fun as it would be to see the residents of Springfield stick with the team, remember that they did go 2-28 in league play against fellow beer leaguers the previous year, needed the help of literally a magic bat to improve in ‘92, and went into the ninth inning of the championship merely tied, despite Strawberry's nine homers. Now, you've put them into the highest league in the land. So it’d be bad. How bad?

Well, think about it this way. In real life, Jim Levey had the worst-ever position player season, -4.0 WAR in 1933, and also the fifth-worst, -3.3 WAR in 1931. Yet even he was good enough to play 17 seasons of professional baseball and parts of three years in the National Football League, plus join the Marines. (Ironic aside: He actually did end a game with a walk-off hit-by-pitch, just like Homer did. He is smiling upon us.) Maybe Groundskeeper Willie could match up to that, but could Carl Carlson? Frank Grimes? We argue not. If Levey was a -4 WAR player, Springfieldian position players are -10 WAR full-season apiece, at best.

Do the same thing for pitchers – the worst season was -2.2 WAR from Steve Blass in 1973, the year that his sudden inability to throw strikes cost him his career – and we’re saying Lenny Leonard is, charitably, a -5 WAR full-season pitcher. There are 9 more of him, too. Take this approach, throw in some playing time estimates, and now we’ve got a roster, one that has nine Major Leaguers and 16 major losers.

Then, we'll swap out those 16 non-ringers with replacement-level (0.0 WAR) players, and then finally with league-average (2.0 WAR) players, too, giving us three ways to look at it. Then, we’ll get to the fun part. We’ll do the exact same thing via simulation thanks to a copy of Lee Carvallo's Putting Challenge -- sorry, we mean MLB The Show -- with 1992 rosters uploaded, and changing the rest of Springfield's roster to suit our needs.

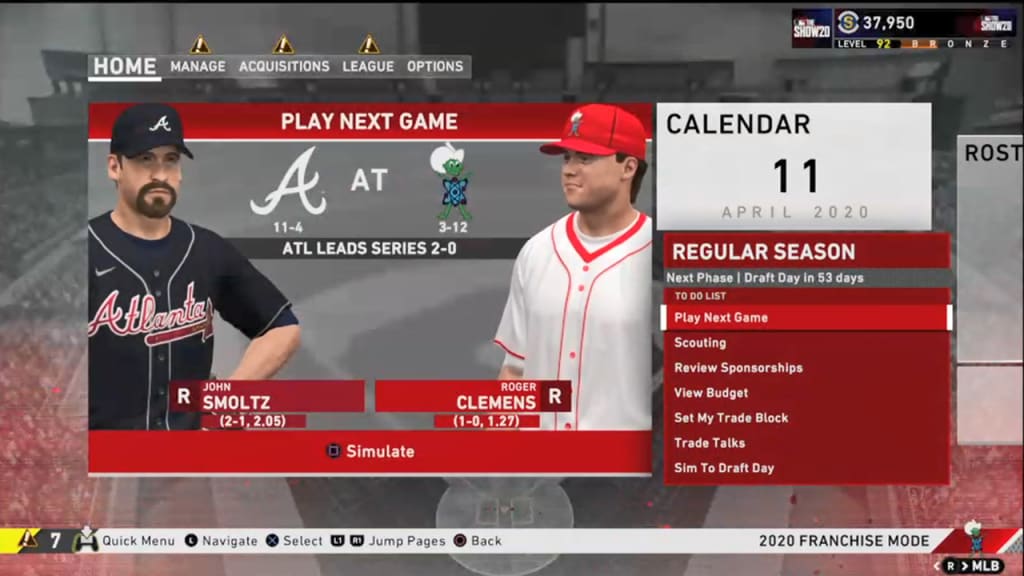

For MLB The Show, we chose to sub Springfield in for the Marlins, in part because they did not exist as a real team in 1992, and in part because Florida definitely borders Ohio, Nevada, Maine and Kentucky, as is canon for Springfield’s home. Yes, we updated their uniforms.

Here’s what happened.

* * *

"No matter how good you are at something, there's always about a million people better than you.” – Homer to Bart. “Gotcha. Can’t win, don’t try.” – Bart

With our tests in place, we ended up with three wildly different results.

1 – With Springfield residents as filler

What WAR suggests: This team would be absolutely dreadful.

Every game not started by Clemens is a near-guaranteed loss, and the bullpen makes sure to blow some of his starts, as well. This group would be worth approximately -29 WAR, and since the general shorthand is that a 0 WAR team would win about 48 games, this is a 19-143 club. Maybe that seems extreme, but remember that about 85% of their innings have to come from unathletic amateurs who may or may not have crayons stuck up their noses. We cannot overstress that this team went 2-28 against similarly unathletic amateurs just the year prior, and that was considered a good season. Now they’re in the Majors.

In real life, the weakest batting club in the 162-game era was the 1979 A’s, who lost 108 games. The weakest pitching club was the 1974 Padres, who lost 102. Combine them, then make it worse. This is worse.

What happened in MLB The Show: This team was … absolutely dreadful, which is a nice confirmation of the WAR test.

We ran this twice, making sure every other player had a ranking of no more than 5 on the 0-99 scale. (We adjusted the ringers for their weighted 1990-'92 WAR so Clemens, for example, was a 98.) The first season came out to 27-135. Clemens went 15-8 in 241 innings over 33 starts, with a 2.17 ERA. Every other pitcher combined won 12 games, somewhat surprisingly. One particularly tortured reliever was asked to pitch in 100 games, and posted an 11.17 ERA for his trouble. We didn't give him a name. Let's say it was ... Moe.

While Griffey Jr. mashed 32 homers, which everyone agreed was preferable to learning the terrifying truth, the beer leaguers combined to hit … zero. Not one. Perhaps they shouldn't have selected "feather touch."

On a second try, it was mildly better at 34-128, as Canseco hit 40 home runs. Despite Clemens throwing 235 1/3 high-quality frames this time, Springfield allows 1,608 runs, shattering the previous record by nearly 35%. One reliever went 0-21 in only 74 2/3 innings. This one can be Superintendent Chalmers, moonlighting for the power plant team. Perhaps the most impressive part was actually managing to get through 74 2/3 innings.

OK, so that didn’t work, but maybe that’s not surprising. If there’s anything we’ve learned from the Angels over the last several years, it’s that some elite all-time great stars aren’t enough to succeed if the roster isn’t deep around them.

2 – With replacement-level Major Leaguers as filler

Burns is cheap, but maybe he’s not willing to abide failure on that scale. Having shelled out for the big-ticket names, he might at least be willing to front the Major League minimum for competent baseball players. Not star ones, necessarily, but competent ones. For example, Matt Davidson had a perfectly replacement-level career (-0.1 WAR) in parts of five seasons. He also hit 52 homers and once struck out Giancarlo Stanton. He was good, comparatively.

What WAR says: Well, it's better. Simply going from untenable players to pro ones changes our projection from -29 WAR to +33 WAR, which is a nice indication of how valuable simply having below-average professional baseball talent is. That should be about a .500 team. It’s not great, but it’s something.

What happened in MLB The Show: This time, we supported our stars with players who had ratings in the 40-50 range. Since this is 1992, that means we’re talking guys like Nelson Liriano, a second baseman who'd compile 1.4 WAR in parts of 11 seasons, or Todd Van Poppel, a highly touted prospect who would go on to post a perfectly replacement-level career. Not stars, again, but still professional baseball players.

This time, it went a lot better, but not great. A 74-88 record may be perfectly cromulent, but it’s still not good. Once again, the stars were great – Griffey Jr. led the league in homers with 36, Smith stole 34 bases and Clemens went 23-4 – but Van Poppel was 2-10 and the likes of Jeff Musselman and Steve Ontiveros weren’t exactly picking up the slack.

A second attempt ended similarly, 79-83. No, this won’t do either. Even stars need some help.

3 – With average Major Leaguers as filler

The key, here, is remembering that “average” isn’t bad. It’s actually quite useful. In WAR terms, a 2-WAR player is considered “average,” and in real 1992, names like Eddie Murray and Gregg Jefferies were in that range. Those are names you can win with … in theory.

What WAR says: Average doesn’t buy us new stars, but it does provide us a roster with no weaknesses around our core of ringers, and wouldn’t you know it, that suggests a really, really strong team, something in the neighborhood of 102 wins.

What happened in MLB The Show: This time, we’ll upgrade to players with a ranking between 70-80, which gives us more notable names like former Cy Young winner Rick Sutcliffe (who, in 1992, was 36 and having his last strong season) or Todd Stottlemyre, who was at the time trying to gain his footing in the bigs.

This time, Clemens is backed by Sutcliffe, Kirk McCaskill, Jim Deshaies and other actual decent pitchers, and now we’re talking, because Springfield sets the all-time win record with a scorching 119-43 mark. This time, when Canseco is injured, longtime vet Joe Orsulak steps in to hit 12 homers. When the rotation hands a lead to the bullpen, Mel Rojas is there to collect 47 saves. The value of a full roster has never been clearer.

Let's be exceedingly clear about this: We ran the simulation that came out to 119 wins first, then only much later realized this picture existed. It's a sign!

This first version of the new, improved Springfield team falls in the NLCS. A second run leads to a similar regular season – this time, 115-47 – and another playoff loss, while a third try led to a 113-49 record and ends with the title Mr. Burns so badly wanted coming to Springfield, though he presumably didn’t expect Derek Lilliquist to be getting the final out.

Maybe that’s the real lesson, anyway. A team full of superstars is a pretty nice to thing to have for a single game, even a roster with four future Hall of Famers. (Smith, Griffey, Boggs ... and Simpson.) It’s a great way to win a wager with a rival power plant.

But if you’re trying to play a six-month season, and really get somewhere? Wade Boggs and Ken Griffey Jr. might be vital, but so, too, are Joe Orsulak and Kirk McCaskill. We can bet that Mr. Burns didn’t see that coming.