Considering that he was in New York City over the weekend to accept his Gold Glove Award, perhaps it shouldn't be surprising that the first thing people noticed about Astros World Series MVP Jeremy Peña was his glove.

"He made some plays even pros couldn't make," Ken Wnuk, his coach at Classical High School in Providence, R.I., told MLB.com. "There was a ball hit on the second-base side of second base. Probably about three, four feet. He ran over, scooped it up, did a pirouette and then threw the kid out at first by about a step. And I mean, he rocketed the ball. The first baseman came over to me and he said, 'Coach, he rips when he throws. That's a hard throw.'"

"I swear to god, in my career, if you look at my best recruits, it took 30 seconds [to recognize their talent]," Steve Trimper, Peña's former coach at the University of Maine, said. "Well, I would say Jeremy was like three seconds."

Peña's family -- his father is former St. Louis and Cleveland big leaguer Gerónimo Peña -- moved to Rhode Island from the Dominican Republic when Jeremy was 9 years old. His parents wanted to provide a brighter future with more options for schooling, which they found in the capital of smallest state in the country.

"It was tough because it was different," Peña said while visiting the MLB offices. "Like, the culture, the food, the weather. That was the biggest shock, not speaking English, not being able to talk to whoever I wanted to talk to. But aside from that, I had a great time. It was easy because I had my family there, my brothers. I made friends at school, made friends through baseball, and then after a year, it was easy."

Peña lived in a diverse section of town, so many of his classmates spoke both English and Spanish -- and there was plenty of good Dominican food to find being cooked both at home and in the neighborhood -- which helped ease the transition.

While Peña had already made a name for himself in the local baseball scene, helping Providence nearly reach the Little League World Series in 2010 ("Don't remind me! I'm still sensitive!" he said with a laugh), there was no guarantee that the scouts would find the young kid with the great glove. New England may be sports crazy, but the weather can wreck havoc on a ballplayer, leading many of the region's best to leave for Florida, Texas or California to get the necessary games and at-bats in.

The first time Wnuk saw him was at baseball tryouts inside the Classical gym because the fields were too wet to hit grounders outside. Still, Peña scooped up everything hit his way.

"I don't [mess] around, I hit the ball," Wnuk said. "I want to see if the kids got enough [guts]. If he's got the talent to get in front of the ball, and I want to see if he can catch it. He was just so smooth. In the front, in between, taking two steps to the left and steps to the right. I must have hit him 40 balls and he missed one."

Trimper nearly missed out his chance to scout Peña at all. Having received tips that there was a special kid playing shortstop in Providence, Trimper rented a car and drove to Providence after the Maine Black Bears had played Holy Cross in nearby Worcester, Mass. But when he arrived at the field, "it started snowing like a banshee."

With the game snowed out and a big game coming up against Stony Brook that weekend, Trimper planned to just chalk it up as a loss and drive back to Orono.

"I'm literally sitting in my car, like the blinker is on, to head back to Maine," Trimper, who is now the head coach at Stetson University, remembered. "And I'm like, 'You know what, let me get a hotel. I came all this way.' I always say, for me, it was that fateful decision to just stay in and stick with it until the snow melted."

When he saw Peña the next day, he was immediately sold.

"It was phenomenal," Trimper said. "He was just a kid back then, so I would say that he didn't show a lot of power at that time, but who does except for a phenom? The one thing I noticed was he took infield/outfield and he had lightning-quick hands. I'm like, I don't care if this kid hits .096 for us, I'm taking this kid to Maine, he's our shortstop. He's gonna save us so many defensive RBIs."

While the world may have been slow to catch on to the shortstop, Peña was never concerned.

"It was different for me because of my experience having a father that played in the big leagues," Peña said. "So, seeing him every single day and talking to him, it felt like it was something I could do. It was different for me because I had that role model in my house."

When Peña showed off his skills at a Perfect Game showcase -- the first tournament that took him out of the state -- new schools came calling. But he remained committed to the university and coaching staff that first took an interest in him.

"Maine came at me early. I think it was my sophomore year," Peña said. "And I was a little kid, you know, skinny. I wasn't the best, I wasn't the fastest, I wasn't the strongest. But Steve Trimper and Nicholas Durba, they saw something in me that I didn't see at the time and other schools definitely didn't see at the time. Once I went to that Perfect Game tournament, and I got exposure and all the other schools start showing up and there were talks for the Draft, I was like, You know what, I'm going to stick with the people that believed in me from Day 1."

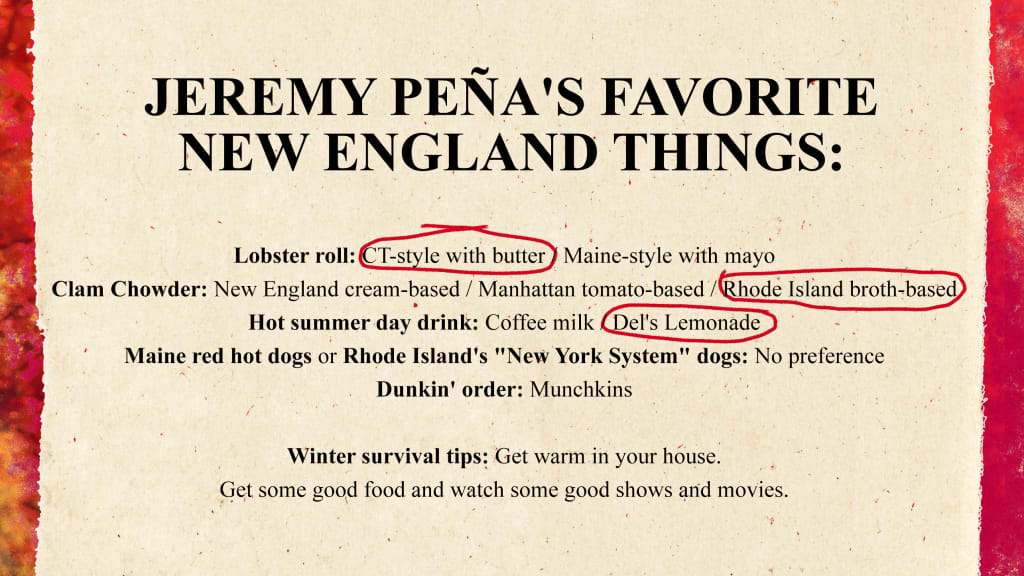

Though he may have been playing way up north with very few home games and lacking the attention he might find in other places, he loved his time there. In the summer, there were beautiful parks and paths through the wilderness he could hike. He loved to fish. The winter, though, was a little harder.

"You lock yourself in your house and sleep," Peña joked. "You watch shows in your apartment."

That's not entirely true, though -- at least, according to Trimper.

"Jeremy literally hung a tire," Trimper said. "I remember in his apartment or dorm room in school and he's banging on this tire in his apartment in the ice and cold, just trying to get stronger."

"When I got to Maine, it was the first time when I actually start working out. I never did weights, started eating more," Peña said. "Just being around the guys, too. Like these guys were driven. They're stronger than me, bigger than me. So, I was always striving every single day to try to get to their level. And I say we just fed off each other."

While Wnuk and Trimper knew they had a special player, even they couldn't necessarily predict what the skinny shortstop from Providence would become: A Gold Glove-winning World Series MVP who cracked out 22 home runs in his rookie season. But they knew the kind of work ethic he had -- and more importantly, they knew the kind of person he was.

"He is the most selfless player I think I've coached in 30 years, where he wants to compete and win so much," Trimper said. "But he wants to do it not because he wants a record, or even a contract, it's more because he gets the joy of winning. Competing and winning -- that's his addiction."

"If a kid made an error on the team, as the guys are coming back in, he'd go to them, 'We'll get them next inning,'" Wnuk remembered. "It was never, 'Jesus Christ, make the play,' it was always, 'We'll get them next inning. Plant your feet, blah blah blah,' He would always help somebody."

Wnuck remembers one of those days some Major League scouts were around the Classical field, taking a peek at Peña. One of the scouts asked him, "What do you think?"

"I said, 'He's the best kid I've had in 30-something years. This kid is good," Wnuk said. "And the guy discounts it, like, 'All the coaches say that about their kids.' I said, 'Buddy, you don't know me. I don't bull--. If the kid [stunk], I'd say, nah, don't bother wasting your time.' This kid is good.

"One of the other scouts, the scout from Houston, looked at me and gave me this smile like, 'Yeah, you're right. Tell him to shut up.' And [years later], they ended up drafting him."