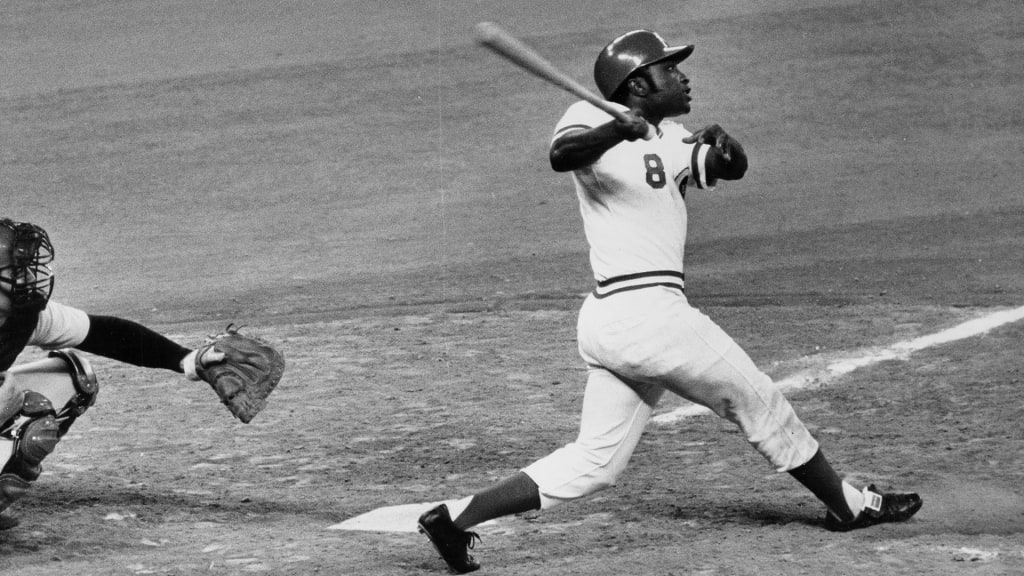

The way you remember Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, who passed away on Sunday at 77 years of age, might entirely depend on when you came of age as a baseball fan.

If you're an older fan, you might recall him as the young star who made his debut two days after his 20th birthday and helped push the expansion Colt .45s/Astros into relevance. If you're a little younger than that, it's probably as the heart of the Big Red Machine in Cincinnati, a two-time MVP who won two rings. Maybe you remember the "Wheeze Kids," when he rejoined with Reds teammates Tony Pérez and Pete Rose for a World Series run in Philadelphia in 1983, or, for over two decades, part of ESPN's Sunday Night Baseball broadcasting team along with Jon Miller, or even as one of the voices of the popular MLB 2K video game series.

If you were fortunate enough to know him in person, as Eduardo Pérez was when he shared his thoughts on MLB Network on Monday morning, your memories might be far more personal. There's no shortage of ways to remember a man who was involved in assistance for disabled children, won a civil rights lawsuit, famously loved jazz, suffered the worst of racial insults as a young player, wrote a controversial letter about entrance into the Hall of Fame, and later became the namesake of a briefly famous site dedicated, mostly, to yelling humorously about broadcasters.

But before all that, he was simply a ballplayer, one of the greatest of all time. If you saw him play, that might seem redundant. Well, of course he was. Didn't you see what he could do? But for those of us who never got the chance to watch him -- his last game, for the 1984 A's, came nearly four decades ago, meaning most anyone under 50 has no real recollection of him on the field -- it's important to remember he wasn't just a baseball legend. He was legitimately one of the greatest players who ever lived.

We can quantify that, obviously, using methods both old and new. While you might think that Wins Above Replacement, which obviously didn't exist during Morgan's career, can't adequately capture all that he did, it's certainly a good place to start. (We're using the FanGraphs version.)

Most Wins Above Replacement, second basemen (1901-pres.)

130.3 -- Rogers Hornsby

120.5 -- Eddie Collins

98.8 -- Morgan

84.4 -- Nap Lajoie

Of course, we're talking about different eras, and then some. Hornsby was born in 1896, Collins was nine years older. Both were finished with their playing careers by the time Morgan was born in 1943, and the sport they played only vaguely resembled modern baseball; no cross-country travel, no night games, no integration, few relievers. Neither ever played west of St. Louis. Morgan, meanwhile, broke into a sport with 20 teams in 1963, and left one 21 years later that had him playing games in Seattle and Toronto.

So if you want to say he was the greatest second baseman of the last 100 years, you'd get no argument. If you want to take into account the change in eras and say he was the best second baseman ever, that's easy enough to argue, too. Set aside second base, really. He's tied for 20th-most all-time in Wins Above Replacement, just behind Rickey Henderson and Jimmie Foxx, just ahead of Eddie Mathews and Carl Yastrzemski. There's Hall of Famers, and then there's Hall of Famers.

It's not hard to see why, either. It's because when you look at all-time greats, you're generally looking for either elite peaks (like Sandy Koufax, who had a relatively short career) or sustained excellence (like Hank Aaron, who kept on hitting for over 20 years). Morgan, however, had both.

Long-running excellence

Of his 22 years in the Majors, 19 of them (setting aside youthful cameos in 1963-'64, and 1968, when he injured his knee 10 games into the season) featured Morgan getting at least 350 plate appearances. In every single one of those 19 seasons, he was an above-average hitter. (Here we're using OPS+, which sets '100' as league average for that year.)

Nineteen isn't the most ever. Morgan was a great hitter, not the greatest hitter. But as you can imagine, it surely rates well, and no one else on this list needs any introduction.

Most average or better hitting seasons, min. 350 PA

22 -- Ty Cobb

21 -- Barry Bonds

21 -- Hank Aaron

21 -- Carl Yastrzemski

21 -- Stan Musial

19 -- seven tied, including Morgan and Willie Mays

Even at age 40, in that final season with his hometown A's (while he was born in Bonham, Texas, he went to high school and college in the East Bay) Morgan posted a slightly above-average 104 OPS+, not that anyone was paying attention to OPS at the time. Only four players who stepped to the plate at least 400 times that year had a higher walk rate than his 15.1%.

But in addition to the longevity -- only 14 players had more 2-WAR seasons than his 17 -- he had the peaks. His 1975, when he was 31, wasn't just his best year. It was one of the best years anyone's had, ever. He followed it up with one that was arguably even better.

That 1975-'76 peak

The 1975 Reds -- the Big Red Machine -- are in anyone's conversation for the greatest team in history. Having lost the World Series in 1970 and '72, the '73 Reds lost to the Mets in the NLCS, and the '74 team finished second in the pre-Wild Card era to a 102-win Dodger team, despite winning 98 games of their own.

But that '75 team, the one that won 108 games, swept the Pirates in the NLCS, and beat the Red Sox in seven games in one of the most thrilling World Series ever, was the peak. They had three Hall of Famers in the lineup (Morgan, Tony Pérez, and Johnny Bench), would have had a fourth (Pete Rose) if not for his own self-destructive actions, and were led by a Hall of Fame manager, Sparky Anderson.

Chief among them was Morgan, who won the NL Most Valuable Player Award that year with 21 of 23 first-place votes -- Rose took the other two -- by putting up a season that looked like this:

• .327/.466/.508

• 169 OPS+

• 17 home runs

• 67 stolen bases

• A Gold Glove, his third in a run of five straight

• 11 WAR

The 169 OPS+ was the best in baseball that year, and the 67 steals were third-most. That 11 WAR, by FanGraphs' reckoning, is one of the 25 greatest seasons of all time, behind a bunch of years from players who need only be identified by their first names: Babe, Barry, Mickey, Stan and so on.

The next year, 1976, another MVP season and another World Series title, was arguably better. Though the WAR wasn't quite as high due to lesser ratings from the prehistoric defensive metrics of the time, Morgan hit for more power (27 homers, a 1.020 OPS) and still stole 60 more bases.

It was, according to MLB.com's Andrew Simon, the only season in the history of baseball where a hitter scored 100 runs, drove in 100 more runs, walked 100 times and stole at least 50 bases.

In the integrated era of baseball, it's by far the best offensive season from a second baseman who had at least 300 plate appearances and qualified for the batting average title. (We normally wouldn't have to say both of those things, but ... 2020.) In second place? Morgan, 1975. Also in the top six? Morgan, 1974. And rounding out the top 10? Morgan, 1973.

Best hitting seasons from 2B, since 1947

186 OPS+ -- Morgan, 1976

169 OPS+ -- Morgan, 1975

165 OPS+ -- Bobby Grich, 1981

162 OPS+ -- Jeff Kent, 2000

160 OPS+ -- Jose Altuve, 2017

159 OPS+ -- Morgan, 1974

157 OPS+ -- Rod Carew, 1975

155 OPS+ -- Daniel Murphy, 2016

155 OPS+ -- Altuve, 2016

154 OPS+ -- Morgan, 1973

154 OPS+ -- Jackie Robinson, 1951

Remember, also, that OPS+ isn't really accounting for skill on the bases, so this is basically saying that "Morgan minus stolen bases was still an all-time great hitter."

Morgan, in his first five seasons in Cincinnati (1972-'76), hit .303/.431/.499, with 108 homers and 310 steals. (That's an average of nearly 10 WAR per season.)

He could hit for average, power, steal a base, field well, and could he ever draw a walk. That part, that underappreciated plate discipline, is worth a section entirely of its own.

The power of a walk

Despite Morgan's later-career disdain for advanced metrics, the irony of it all is that for all the accolades he received during his playing days, he might have been more appreciated now than ever, and that's because even in years where he wasn't posting high batting averages, he was always, always capable of getting on base via a walk. (In 1980, for example, in a brief return to Houston, he hit only .243, but still finished second in the Majors in walk rate, leading to a solid 115 OPS+.)

In the modern history of baseball, dating back to 1901, Morgan's 16.5% walk rate comes in at ninth, among all players with at least 6,000 plate appearances. That helped him put up one of the all-time hilarious batting lines in the 1976 NLCS, when he failed to get a hit in 13 plate appearances, yet walked six times, giving him a line of .000/.462/.000.

"I was hitting about .280, and I was talking real cocky, and [Houston teammate Ron] Brand said to me, 'Joe, a lot of guys hit .280, but there aren't any other players in baseball who can get on base like you can. That's what you should be proud of, not your .280.' At the time I didn't take what he said in the right way, but now I'm proud of all the walks I get."

Later in the interview, he expressed a thoroughly modern thought -- "I also watch films for hours on my video machine" -- before gracing us all with this anti-slump poem that would fit in perfectly in today's game.

Morgan entered the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 1990, and by whatever measuring stick you choose to use, he's one of the all-time greatest to play the game. One of only 13 players to win back-to-back MVP Awards, likely the single greatest position player of the 1970s, the best player on what might have been baseball's best team, Morgan more than earned his place among the inner-circle greats.