In case you’re wondering whether it’s unusual for the Braves to be using Jorge Soler -- a player who is large and powerful, but not terribly fast or renowned for his contact or on-base skills -- atop their lineup, as they’ve been doing for the past four games, know that Atlanta manager Brian Snitker saw it coming.

“I like Soler there,” Snitker said. “I figured he’d want to drug test me after he looked at the lineup.”

We have no intel on whether Soler actually did consider such a request. We can, however, offer this: Unusual? Try borderline unprecedented. It's incredibly rare to see a situation like this on more than a one-off basis.

What we mean by that is that for about a century and a half of baseball, leadoff hitters followed a certain expectation. They’d be fast above all else, they’d work a count, they were often middle infielders or center fielders, power was a bonus but not a requirement and, in many cases, they were not physically large. Think Kenny Lofton, or Pete Rose, or Vince Coleman.

Just look at Thursday, really. There were 12 games across the Majors, and of the 24 leadoff men, 19 were middle infielders or center fielders. Four more were starting in outfield corners or at DH, but with extensive histories at second base or center field. Aside from Pittsburgh third baseman Ke’Bryan Hayes, the outlier here … was Soler.

That traditional perception of what a leadoff hitter must be has changed a little as power has become more valued -- think Ronald Acuña Jr. or Trea Turner, who can slug a homer as well as steal a base -- but the general idea is there. For generations, speed atop the order was treasured, power was nice-to-have and, until extremely recently, the love for speed overshadowed the demand for on-base skills, which is how Billy Hamilton and Juan Pierre spent so much time atop lineups.

It was, for decades upon decades, just how it was done.

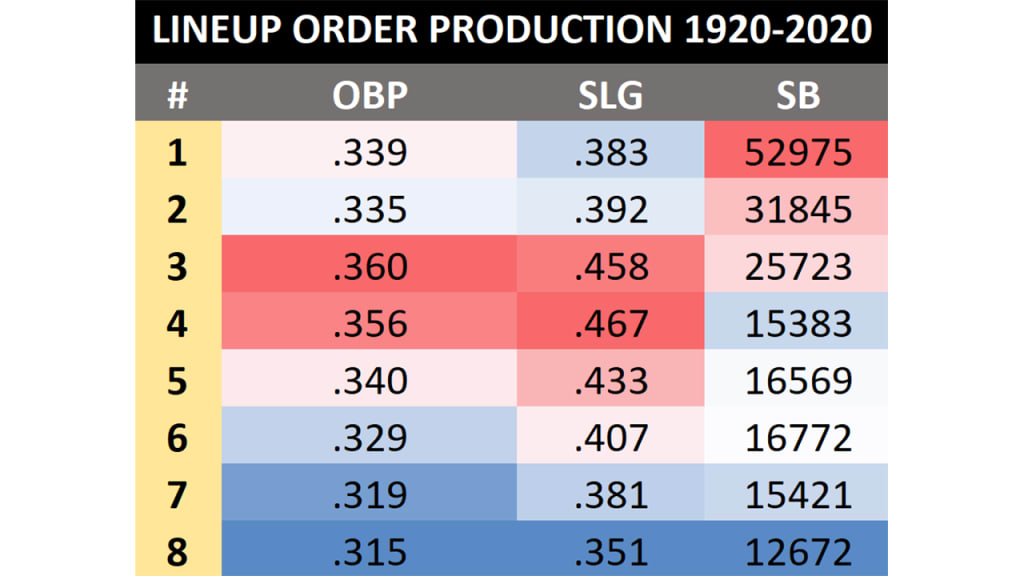

You can see that by looking at the lineup spots in the century from 1920-2020, leadoff men had the fourth-best OBP of the top eight spots, the sixth-best slugging percentage … and more stolen bases than the four-through-six spots combined.

Soler, however, is not fast. In eight seasons, he has 10 stolen bases and three triples. Last year, he was in the 41st percentile of Statcast sprint speed, and this year, he’s in the 44th, making him slightly below average.

He’s not small -- listed at 6-foot-4, 235 pounds, he’s the second-heaviest active Braves position player -- and he’s far from a middle infielder. While he’s played a competent right field for Atlanta, his best position is designated hitter, which is where he’d spent the majority of the past three seasons with Kansas City. Nor, really, does he have an elite ability to get on base; his career on-base percentage is .330; the Majors during his career have had a .320 mark.

He does have outstanding power -- in 2019, playing in one of the hardest parks to homer in, he led the AL with 48 blasts -- but that kind of profile, the large powerful slugger with unimpressive speed and decent-but-not-great on-base skills has, throughout history, hardly ever been seen atop a lineup in more than a cameo appearance.

It’s that fact which brings us back to the nearly unprecedented nature of it all. It’s not that no large, powerful sluggers have ever led off; Aaron Judge did it for a single game in 2019. Soler himself did it once in 2015. But we’re not talking about one-offs here, we’re talking about players who have come this far in their career without outstanding speed or on-base skills, and without leadoff experience, who then were asked to start doing it. When has that happened? Not often.

So that’s what we looked for. We went back to the start of AL/NL baseball history, looking for players with Soler-esque careers, which we defined as “players who, through their first 600 career games, had no more than 10 stolen bases, an OBP no higher than .330 and had hit leadoff no more than five times.” Finding that group, we then asked: OK, did any of those guys then go on to lead off at least four times, as Soler has?

The answer is: Really only once that feels the same. It’s actually three times, but light-hitting 1970s infielder Danny Thompson (15 homers in seven seasons) hardly fits the spirit of this, and Wilmer Flores’ six leadoff starts for the 2019 D-backs were scattered throughout the year, not the result of a new plan.

The one similar instance came back in 2011, when Baltimore leadoff man Brian Roberts -- a small, speedy middle infielder -- suffered a concussion in May and, after Robert Andino and Felix Pie failed to fill the spot, was replaced by shortstop J.J. Hardy, who had six stolen bases, a .323 OBP, and 81 homers in six previous big league seasons. (He homered in his first at-bat, led off 63 more times that season ... and then never did it again.)

That, really, is it, which might make this an NL first.

Yet we come not to bury Snitker for this unexpected choice, but to look at the context of it and to say: We understand. Sort of. Because while using a player like Soler atop the order is a non-traditional choice, there are signs that the Braves themselves are changing the way they approach things, like in their use of shifts:

Remember, too, how Atlanta got to this point. Just before the All-Star Game in July, regular leadoff man Acuña Jr. injured his knee and was lost for the season. After a few games with backups Ehire Adrianza and Abraham Almonte, the Braves made a move to acquire Joc Pederson from the Cubs and inserted him at the top of the order.

Pederson actually did quite well there (an .829 OPS leading off in July), as did the offense behind him (Atlanta had the third-most runs in baseball in the two weeks after the All-Star break). Still, the outfield situation got shuffled at the Trade Deadline when the Braves traded for three outfield veterans in Soler, Eddie Rosario and Adam Duvall, so in search of a consistent name to pencil in at No. 1, leadoff belonged to Ozzie Albies for all of August and into September.

Albies looks the part -- he’s a 5-foot-8 second baseman with 17 steals this year -- but his good-power, just-OK-on-base-skills profile is actually similar to Soler’s, and he hit only .229/.282/.458 in 39 games atop the order through last Sunday before being moved back down to the third spot.

“It kind of felt like we had to maximize Ozzie better, and I like him hitting [third],” Snitker said.

Which brings us to Soler, and choices. Lineup construction is always, constantly overrated in the sense that it usually does not make that much of a difference beyond “put your best five guys first and your three weakest guys last.” (Most research suggests we’re talking about a few runs per season of difference, not a few wins, between reasonable lineup choices.)

Snitker has done that; for weeks now, the top five has been Soler, Albies, Freeman, Austin Riley and Duvall in some order, with Dansby Swanson, the catcher and the third outfielder (Rosario, Pederson or Guillermo Heredia) making up the bottom third. That’s all fine.

But within those top five, the leadoff choices are limited. Albies didn’t work out. Freeman and Riley are your best hitters, and it’s long been suggested the best hitters should bat second and fourth -- as they’re now doing. Duvall (.292 career OBP, .287 this year) has 37 homers, but is generally poor at getting on base, making him a worse leadoff pick than Soler.

All of which means that Soler, somewhat by default, is a perfectly reasonable choice, if not necessarily a traditional one. After all, of the available Braves hitters, only Freeman and Riley are projected to have better on-base percentages, and there’s compelling reasons to have them in spots to drive runners in.

“It’s not prototypical or how you would draw it up, but I think a lot of things are changing in the game,” Snitker said, and that’s exactly right. Just because you couldn’t or wouldn’t do this in 1921 or 1971 doesn’t mean you couldn’t or shouldn’t do it in 2021, if it makes sense enough.

Soler won’t steal bases in a big spot. He probably won’t go first to third, or be fast enough to motivate Snitker to start dropping sacrifice bunts with his No. 2 hitter. (Which, considering that’s now Freeman, is probably a good thing.) He won’t look like any leadoff hitter you’ve really ever seen, just like Albies doesn't look like the kind of hitter who should have 30 home runs. Soler is not really the leadoff hitter any playoff team would expect or desire to end up with.

But given the choices at hand, and how much has changed about how the leadoff hitter “should look like,” this unusual pick makes a surprising amount of sense. Soler doesn't look the part. Then again, these kind of choices really never should be about looks, should they?