David Montgomery once said that his parents bought their first television, when he was 4 years old, so they could watch the Phillies in the 1950 World Series. When he grew up, he played ball at Wissahickon Park near his home in the Roxborough section of Philadelphia.

Years later, Montgomery could still recite every turn of the 20-minute drive to Connie Mack Stadium. As an undergrad at the University of Pennsylvania, he sat in the bleachers with friends and watched the games while competing to see who could eat the most hot dogs and ice cream.

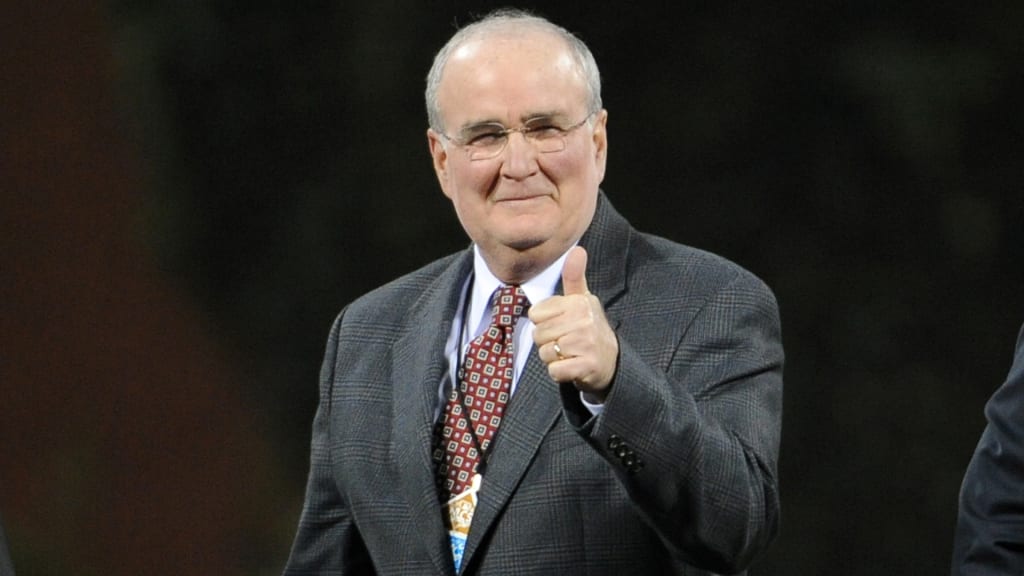

From that typical teenaged-fan upbringing, Montgomery used his intelligence and work ethic and a well-placed break or two to become the face of the Phillies’ front office and a behind-the-scenes force in Major League Baseball for decades. He was club president when the organization transitioned from Veterans Stadium to Citizens Bank Park in 2004 and during the most successful period of sustained excellence in franchise history, from ‘07-11, which yielded five straight National League East titles, two pennants and the '08 World Series championship.

Montgomery was so influential at MLB’s New York headquarters that he was considered a legitimate candidate to one day become Commissioner.

After spending nearly a half-century in baseball, the widely admired Montgomery passed away Wednesday morning at the age of 72 after a courageous five-year battle against jaw cancer. And when he did, his most enduring legacies weren’t wins and losses or the considerable power he wielded. No, Montgomery's legacies were his unwavering civic-minded approach to the business of baseball, his familial attitude toward a front office that expanded dramatically under his watch, his fierce loyalty and his passion for the game.

“David was one of Philadelphia’s most influential business and civic leaders in his generation,” said Phillies managing partner John Middleton, who ultimately became the team’s front man after Montgomery took a leave of absence as president and CEO in August 2014 following his diagnosis that May. “For 25 years, he has been an invaluable business partner and, more importantly, an invaluable friend.

“He was beloved by everyone at the Phillies. Leigh and I are saddened beyond words at David’s passing and extend our love and sympathy to Lyn, his children and grandchildren.”

Montgomery returned as chairman in January 2015 and was believed to be cancer-free before the disease returned with a vengeance early last year.

His absence leaves a large void not only in the executive suite at the ballpark but across the baseball landscape.

“Dave Montgomery -- and I mean this sincerely -- was one of the great human beings I’ve had the privilege to know,” an emotional Commissioner Emeritus Bud Selig said from his Milwaukee office. “From the time I met him in the early 1970s, he was amazing. Schedules. Wild Card. Interleague Play. Everything. I can’t tell you the contributions this man made to the game.

“When we had deliberations on all the things he and I worked on, you want to know something? I never heard him talk about the Phillies. It was all what was best for baseball. He ran a great franchise. Don’t misunderstand me. He loved the Phillies. But he always put baseball first.

“Nobody worked any closer with David than I did. He spent endless hours working for the industry. Endless hours. We were very close friends. I just had so much profound respect for him. I mean profound. There weren’t very many people I met in my career who were as helpful and cared about the game the way he did. You’re lucky in life if you meet a Dave Montgomery. It doesn’t happen often, if at all.”

Commissioner Rob Manfred also spoke glowingly of Montgomery's character: “I am deeply saddened on the passing of my dear friend David Montgomery. David was a first-class representative of his hometown team, the Philadelphia Phillies, for nearly half a century. He never forgot his days as a fan at Connie Mack Stadium, and he carried those lessons to Veterans Stadium and Citizens Bank Park. David’s approach to running the franchise and serving its fans was to treat everyone like family. He set an outstanding example in Philadelphia and throughout our game.

“David was one of my mentors in baseball and was universally regarded as an industry expert and leader. In recent years, I marveled at his courage as he battled cancer and through it all his amazing ability to think of others.

“I will remember David Montgomery as a gentleman and a man of great integrity. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest sympathy to David’s wife Lyn, their children and grandchildren and the entire Phillies organization.”

In hindsight, Montgomery’s ascent to the upper echelons of baseball management may seem to have been inevitable. Of course, it wasn’t.

After graduating from William Penn Charter School in 1964, Montgomery majored in history at Penn, then received an MBA from the prestigious Wharton Business School in '70. At that point, his life could have taken many directions. Montgomery interviewed with Scott Paper Company, Quaker Oats and even the Philadelphia 76ers.

Montgomery was also serving as an assistant football coach at Germantown Academy and reached out to the father of one of his players. The dad in question happened to be Phillies Hall of Fame right-hander Robin Roberts, who put him in touch with Bill Giles, at the time the team’s vice president, business operations.

Giles recounted what happened next in his 2007 autobiography. “It was one of the more interesting interviews I ever conducted -- taking place, as it did, in a locker room and lasting all of about one minute. [Montgomery] certainly wasn’t expecting to be interviewed that day or he would have worn more than a jockstrap. … He worked out, all right. He succeeded me as CEO in 1997.”

In the beginning, though, Montgomery was making $150 a week, working in the ticket office during the day and helping operate the scoreboard at night. It didn’t take long for him to begin proving himself. Before long, Montgomery was named marketing director, then director of sales before being promoted to executive vice president after the 1981 season, when Giles put together a group that purchased the team from the Carpenter family.

Montgomery became chief operating officer in 1992, then acquired an ownership interest two years later and took over for Giles in June 1997.

“I was just blessed with opportunities,” Montgomery told the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1999. “And because it was the focus of what I was doing, it never felt like a job to me. I was just pursuing my passion in sports.”

At Penn, Montgomery's social circle included Ed Rendell, who would go on to become the mayor of Philadelphia and governor of Pennsylvania, and Mike Stiles, who later became a United States Attorney, then COO of the Phillies.

Rendell likes to tell the story about how he reached out to the Phillies in 1992, after he was elected mayor. The city was broke. The previous summer, only 10 of the 38 public swimming pools had been opened and, even then, for six weeks instead of the normal 10. Rendell vowed to open all the pools for the entire summer. But how?

Soon, starting pitcher Terry Mulholland announced that he would donate $1,000 for each win. The Phillies said they would match that and invited others to join in. Before long, enough money had been raised to not only meet the goal, but also to open four more pools that had been closed for years. Similar scenarios were repeated over and over.

“The Phillies are almost always there,” Rendell said in 2015, noting that the organization’s commitment to charity began under Giles and was continued and expanded during Montgomery’s 17 years running the team. “There are some businesses in town that almost always say no. The Phillies never say no. They pick out the charities that are most in need of help, that can have the most impact on people’s lives, and they support them in so many different ways.”

Said Montgomery at the time: “There are things you can control and things you can’t control. I’ve lived through all those cycles as far as winning and losing is concerned. But you can be consistent in one thing. You can be consistent in your commitment to the community. That’s what we believe in. You’ve heard me say it a hundred times. We’re the Philadelphia Phillies, we’re not just the Phillies. We really do have an obligation to take that visibility and use it to shine a light on people who are doing good work in the community.”

In addition to serving on various MLB committees and alumni work for his alma mater -- he was a trustee, a member of the Board of Overseers of the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts and WXPN, Penn’s radio station -- Montgomery gave his time to several other enterprises, including PHL Sports, a division of the Philadelphia Convention & Visitors Bureau; the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce; Need in Deed, a nonprofit working with children in Philadelphia public schools; the Children’s Scholarship Fund; and the Walnut Street Theater.

Despite his status as a powerful authority figure, Montgomery was venerated around the ballpark for his easy affability and approachability. He seemed to know everybody who worked for the team by name and insisted that they call him by his first name.

At times, that even extended to the players. When Scott Rolen first came to the big leagues, he unfailingly referred to the club president as “Mr. Montgomery.” When the young third baseman became eligible for arbitration, a tongue-in-cheek clause was inserted into the contract stipulating that Montgomery was to be referred to as “Dave” and other members of the front office must be called by their first names as well.

For years, Montgomery was a familiar face at the Palestra for Penn home basketball games.

Even though he was ailing, Montgomery traveled to Cooperstown, N.Y., in July to attend former Phillie Jim Thome’s Hall of Fame induction -- and never mind that Thome was being enshrined as a member of the Cleveland Indians.

Montgomery received numerous honors in recent years. Last spring, the new indoor training facility at the Carpenter Complex in Clearwater, Fla., was named in his honor. Montgomery received the Allan H. (Bud) Selig Executive Leadership Award from the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation, the Ed Snider Lifetime Distinguished Humanitarian Award from the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association and has been recognized by the Mural Arts Program, the Boys & Girls Clubs of Philadelphia and the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education.

And Daisy Field, the same field in Wissahickon Park where Montgomery grew up playing baseball as a kid, now bears his name.

Montgomery is survived by his wife, Lyn; three children, Harry, Sam and Susa; one granddaughter, Elizabeth; and two grandsons, Cameron and Will.

Funeral arrangements are pending.