“Strikeouts are up,” goes the narrative, and in this case, the narrative is fact, because the narrative is true. The topic of strikeouts taking over the game has been a subject of discussion for many, many years, going back to Mickey Mantle being criticized for whiffing back in the 1950s.

Those pesky whiffs are, again, up in 2021 … sort of. To look at the raw numbers, it’s indisputable. Entering Monday, 24.1% of plate appearances end in a strikeout. That’s higher than last year’s 23.4%, and 2019’s 23%, and 2018’s 22.3%, and, well, like we said, the last time it didn’t hold steady or rise was when 2005 saw a slight dip from 2004. You know all this. We’ve broken no news.

Here’s the interesting thing, though: All plate appearances are not created equally. Nearly 30% of the way through the 2021 season, actual professional hitters, the ones paid to hit baseballs with varying degrees of effectiveness, haven’t really struck out more than they did in 2020. If you take pitchers hitting out, this is what it looks like when comparing 2020 to '21 for position players only. (We're breaking our cardinal rule of not showing this to multiple decimal points just to illustrate how close it is.)

Non-pitcher strikeout rate (as of Monday morning)

2020: 23.43%

2021: 23.48%

That's ... nothing. It's the same. So, why, then, is the overall strikeout rate up?

Well, we’ve always said that the No. 1 indisputable culprit of strikeouts are the pitchers, that they throw with increasing velocity and better knowledge of spin and in ever-shorter bursts, that you can blame the pitchers far, far more than you can blame hitters for trying to launch or handle the shift or whatever ... and that’s still true, but in a different way.

This time, you can blame the 2020-21 strikeout increase on pitchers … hitting. Or “hitting,” perhaps more appropriately.

That is, pitchers have always been bad hitters ("every patron of the game is conversant with the utter worthlessness of the average pitcher when he goes up to try and hit the ball," wrote the Sporting News in, wow, 1891?) and now they are worse than ever. Understandably so, of course. They didn't hit in 2020 when the designated hitter was instituted in the National League due to the pandemic. They don't hit in the Minors. They're not around to be good hitters, because they are not hitters.

Furthermore, they’ve struck out, as a group, 47.1% of the time, which, yes, is also the worst of all time. That’s another way of saying that they've whiffed 645 times in 1,370 plate appearances. (The biggest whiffer: Pittsburgh's Tyler Anderson, who has struck out 14 of his 18 times to the plate.)

That massive influx of whiffs -- nearly half the time a pitcher comes up, he will hit nothing but air, if he bothers to try to hit at all -- is responsible for almost all of the increase from 2020 to 2021, because both leagues used the designated hitter in the pandemic-affected 2020 season. That is, in 2018, pitchers batting were whiffing 42.2% of the time. In 2019, it was 43.5%. And this year, back up to 47.1%. At this rate, if pitchers are still hitting in 2040, they will strike out more than 100% of the time they bat. We joke ... but only a little.

So it's not position players who are driving the 2020-21 increase. Furthermore, position-player strikeouts have dropped slightly from April to May.

April: 23.8%

May: 23.1%

Plus, the swinging strike rate of 11.4% is equal to last year’s, making it the first time since 2010 that we haven’t seen an increase.

It’s fair, of course, to note, that comparing 2020 to ‘21 comes fraught with risk, since we’re comparing a season that took place mostly in warm weather to one that’s taken place mostly in the cold, and temperature affects everything. Then again, the highest strikeout-rate month going back to 2010 is September, the second highest is April and the May through August grouping shows little difference. There’s very little first-half (20.6% from 2010-20) vs. second-half (20.9%) strikeout rate difference in recent history.

So, while comparing 2020 to ‘21 is not a perfect use case, it’s not like one season skipped a high-strikeout month and the other didn’t. (That will change when we get to September 2021, of course.)

But wait, there’s more. You’re correctly thinking right now that pitchers don’t last as long in games as they once did, and therefore get pinch-hit for after just one or two plate appearances, somewhat limiting this effect. That’s true. Thing is, they have to be hit for by someone, and that someone is usually a backup (i.e., not good enough to be a daily starter) and subject to the unofficial “penalty” that makes coming in cold off the bench more difficult.

Those pinch-hitters are better than the pitcher batting, but worse than a non-pinch-hitter batting, and wouldn’t you know it … pinch-hitters are striking out more than they ever have, too, 30% of the time this year, though still retaining value via walks and power.

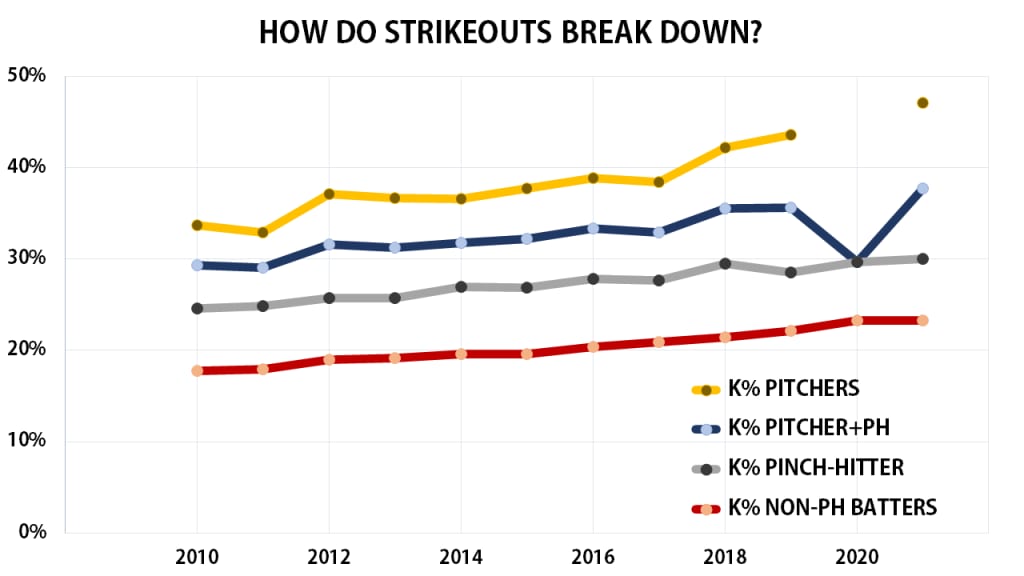

So if you split all the strikeouts into “pitchers + pinch hitters” as one group, and “all other position players” as the other, this is what you get since 2010. Regular position players are striking out steadily more each year. Pitchers have consistently been about 15-20 percentage points higher, though that's about 24 points this year. Pinch-hitters always whiff more than non-pinch-hitters; pinch-hitters and pitchers combined to strike out way more than other hitters. (We looked into filtering only pinch-hitters when hitting for the pitcher, but the difference was negligible.)

All of which is a long way of saying: Position players are trending in the same way they always do, pitchers are hitting worse than ever, and the pinch-hitters replacing them are basically just splitting the difference, leaving some sort of "post-pitcher-hitting" effect even when the pitchers are no longer hitting.

So sure, there's too many strikeouts, and there have been for years, because pitchers are just too good, but when we're looking at larger trends and what's driving them, it's important to remember that pitchers didn't hit in 2020 and may not in the near future, depending on what happens with the DH after 2021.

But if "regular" batters aren't striking out more this season, why is that? The underlying swing and plate discipline numbers aren't that different, nor are batted-ball indicators, and after years of declining usage, fastballs are actually up a tick this year. Shifting is actually down a tick from last year, but there's no increase in hitters going to the opposite field when they hit grounders against shifts. Maybe you'd think hitters are trading contact for power, except hard-hit rate is up this year.

That last part is probably in some part due to the changes to the ball itself, which has also generated discussion that perhaps it has changed pitch movement, though that seems inconclusive so far. (That is, spin rates are up, but spin rates always go up as teams are less interested in employing low-spin pitchers, and pitchers are more effective than ever at converting that spin to movement. And, as we noted, position-player swinging strike rate isn't up.)

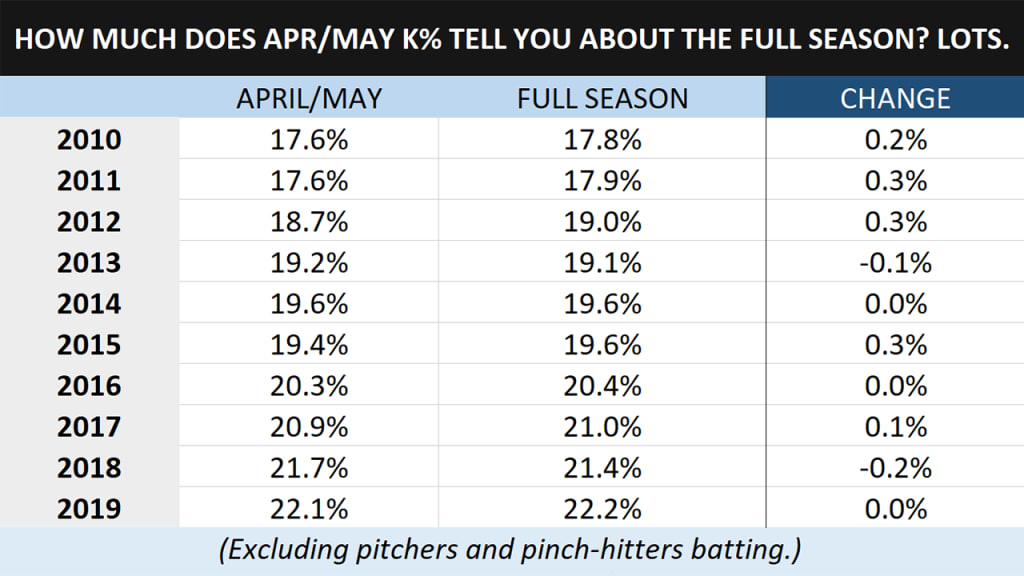

The simple answer is that it's still only 30% of the way through the season, and a high-strikeout September (as we often get) is still likely to push us into "highest strikeout rate of all time" territory. Then again, the (non-pitcher, non-pinch-hitter) strikeout rate in the first two months generally tells you a whole lot about what you'll get for a full season rate.

So maybe what we're seeing now is what we'll get -- which will, of course, be either a record-setting number or close to it.

While it's important to note that pitchers and their massively inflated strikeout rate (and their pinch-hitters and their own big strikeout rates) are carrying some of the burden here, don’t let all of this bury the larger story of what dominant pitching has done to the game; even if you just look at non-pitchers batting, you’ll find that 2021 and ‘20 are still the highest strikeout rate seasons of all time, and pitchers plus pinch-hitters only take about 6% of plate appearances (though they're responsible for 9% of whiffs.) That’s not an issue you get hitters to suddenly "adapt to," and it’s not something you fix by banning the shift (which might actually make the strikeout problem worse).

It’s something you fix with rule changes, just like after the 1968 Year of the Pitcher when the mound was lowered, the strike zone was shrunk, four new teams were added and a few years later the designated hitter was introduced to the American League (all of which came after the strikeout rate held steady or increased each year from 1953 through 1965.) Pitchers didn’t magically get less dominant, that is. They had some help. Baseball was better for it.

Strikeouts, clearly, aren't going anywhere. Pitchers are too good on the mound. They're too helpless at the plate. They're driving this year's whiff increase all around.