A version of this story originally ran in February 2022.

As a kid, Roberto Clemente did chores in his hometown of Carolina, Puerto Rico, to save up for a bicycle, which cost about $20 at the time.

Once he bought one, he would use it to trek into San Juan to watch Puerto Rico’s Winter Baseball League -- one eventually renamed in his honor -- which in the 1930s and ’40s was a sanctuary for Negro League players looking to continue playing in the colder months.

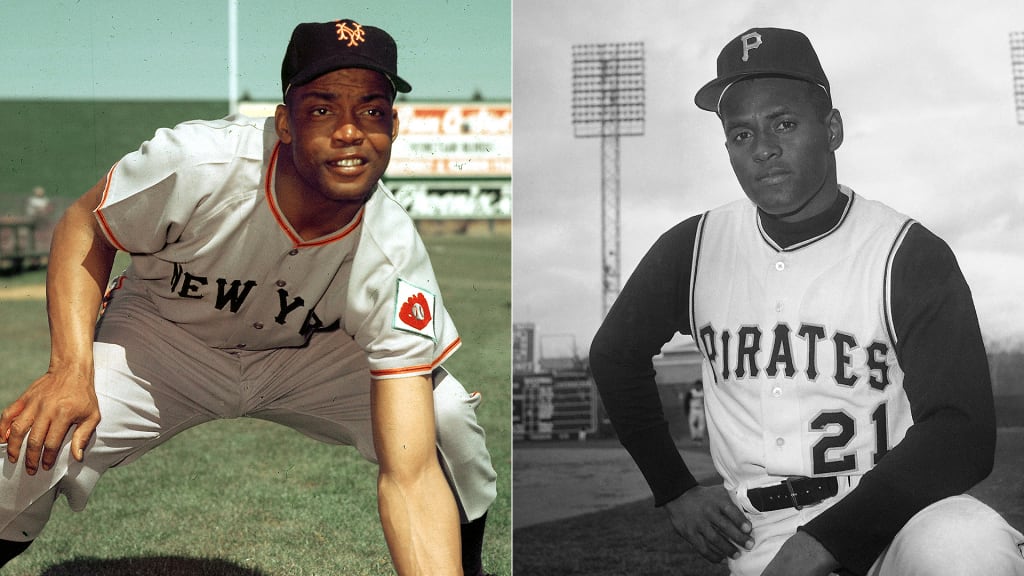

At Estadio Sixto Escobar, Clemente would climb a tree in right field and saddle a branch to look out on the Senadores de San Juan and whichever team they were playing at the time. But in 1945, when Clemente was 11 years old, the youngster would watch one person over all others: Monte Irvin, a member of the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles, who played great defense and made incredible throws from right field.

One special day in that 1945 winter, Clemente didn’t head for his perch in right field. Instead, he walked up to Irvin -- who was born 103 years ago Friday -- and got an experience he’d never forget.

“Monte handed Dad his bag so Dad could walk in for free,” said Roberto Clemente Jr., Clemente’s first son. “And once they went in, Monte opened his bag and gave dad a glove.”

Call it a sign: Clemente went on to be a right fielder like his childhood idol, Irvin. The fact that Irvin gave Clemente a glove would serve as foreshadowing: The Great One would go on to become the greatest defensive right fielder in baseball history with 12 Gold Glove Awards.

But as important as the gift from Irvin was, even more crucial was the example he set for the young Clemente as a fellow minority who was a superstar on the island, with his MVP season for the Senadores. Following in the footsteps of a player who looked like he did when the Majors were taking the first baby steps toward integration, Clemente went on to be a beacon for minority and working class populations.

Irvin was nearly the first Black player in the white Major Leagues. He was recommended by Negro League team owners as one of the best equipped players to join MLB, and Dodgers GM Branch Rickey asked Irvin about the possibility. But Irvin had just returned from service in World War II, where not only was he discriminated against based on his skin color as he had been in baseball, but he also showed symptoms of PTSD.

Clemente moved to Pittsburgh in 1955 after he’d been drafted in the Rule 5 Draft from the Dodgers at age 20 by Rickey’s Pirates. It came six years after Minnie Miñoso joined Cleveland to become the first Afro-Latino in MLB in 1949, the same year Irvin reached the Majors with the Giants.

Before Clemente played an inning as a Pirate, he knew who he was to serve on the field, and it was not just himself. As he took the field against Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers on April 17, 1955, he set an intention.

“He said to himself, ‘I am representing Puerto Ricans. I am representing Latinos, Hispanics. I’m representing Blacks, minorities, anyone of a working class that is suffering out there and suffering from injustice,’” Roberto Jr. said. “And he took that very personally.

“Baseball was secondary to what the name [Clemente] means to people and the impact it has around the world.”

Clemente would only become a stronger player from that first game, though as an Afro-Latino player he had to work twice as hard. Despite baseball being integrated by the time Clemente arrived, prejudices were still strong and hard to overcome, and Latin American players were often unfairly seen as lazy or selfish, especially when they sat out with injury.

A .282 average over his first five seasons didn’t do him any favors, but once the calendar flipped to 1960 and Clemente began to hit over .300 regularly, the honors started to come.

Of course, a cannon of an arm really cemented his legend. Runners feared Clemente, who had an unbelievable blend of throwing strength, accuracy and speedy fielding.

A concise illustration of that fear: On Opening Day in 1965, the legendary Willie Mays took off from second base on a two-out single to right field from Jesus Alou in the fourth inning. Alou advanced to second on the throw home from Clemente, yet the speedy Mays did not attempt to score. The inning ended with the next batter, the game went scoreless in regulation, and the Pirates walked it off in the 10th.

Had anyone but Clemente been out there, Pittsburgh likely would have lost that game.

“When the world’s best baserunner puts on the brakes on a hit to right,” Gaylord Perry said of the play, “you know it’s because the world’s best arm is in right.”

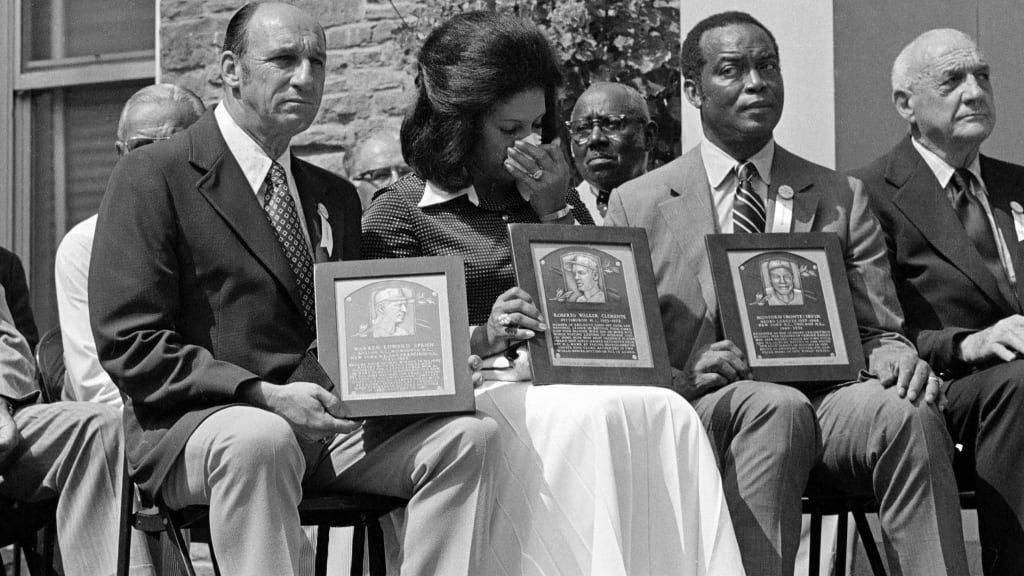

That standoff between two Hall of Famers was inspired in its own right by a lesser-known but just as pivotal Hall of Famer in Irvin. (Clemente and Irvin were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on the same day: Aug. 6, 1973.)

When Clemente watched Irvin from the tree outside of Estadio Sixto Escobar, he didn’t simply marvel at the arm the Senadores’ right fielder had and daydream. He also keyed in on the work Irvin did to be so great.

Clemente would ask teammates to hit him balls to right field so he could create a mental encyclopedia of bounces at each stadium he played in. If he was going to get beat by a baserunner, he wasn’t going to allow it to be because he didn’t get to the ball in time. If he gave himself a step there, he could catch runners by a few steps with his arm.

“Clemente always told me he developed a throwing arm like mine because he'd always admired the way I threw the ball,” Irvin told MLB.com in 2001. “When he got into the Majors, we renewed our friendship. We used to reminisce about the good old days in Puerto Rico.”

And Clemente never forgot Puerto Rico, nor the minority players who lived there year-round or wintered there. He never forgot that intention he set before his first game, even when he went on to be a perennial All-Star and Gold Glove Award winner, that he would serve the underrepresented populations through his greatness on and off the field.

“Always, they said Babe Ruth was the best there was. They said, ‘You’d really have to be something to be like Babe Ruth.’ But Babe Ruth was an American player,” Clemente said after winning the 1966 MVP Award. “What we needed was a Puerto Rican player they could say that about -- someone to look up to and try to equal.”

Clemente became that example, serving as what current Pirates catcher and native Puerto Rican Michael Perez dubbed “a patriarch” of the island. Thankfully, Clemente had an example from childhood to try to equal -- and eventually surpass -- in Irvin.

“The man was a gem,” Roberto Clemente Jr. said of Irvin, “and he did not know -- Monte really did not know -- how much he had to do with Dad and how much of an impact he had on Dad.”