If there’s a word you associate with Ronald Acuña Jr., it might be “loud,” in all the best ways. His home runs are loud. His rocket throws from right field are loud. All the stolen bases, especially in big spots, are loud; the bat flips and celebrations are all loud, understandably. If not for Mookie Betts having a phenomenal season of his own, Acuña would have had a unanimous MVP NL Award locked up months ago, and it's looking likely he's going to finish first regardless.

There’s nothing wrong with loud, because that’s fun, and exciting. But there’s something else Acuña is doing in the midst of his magical season that’s just about as impressive as anything else he’s doing, and it demands our attention as well. It’s not loud. It’s decidedly old school. It’s about making contact.

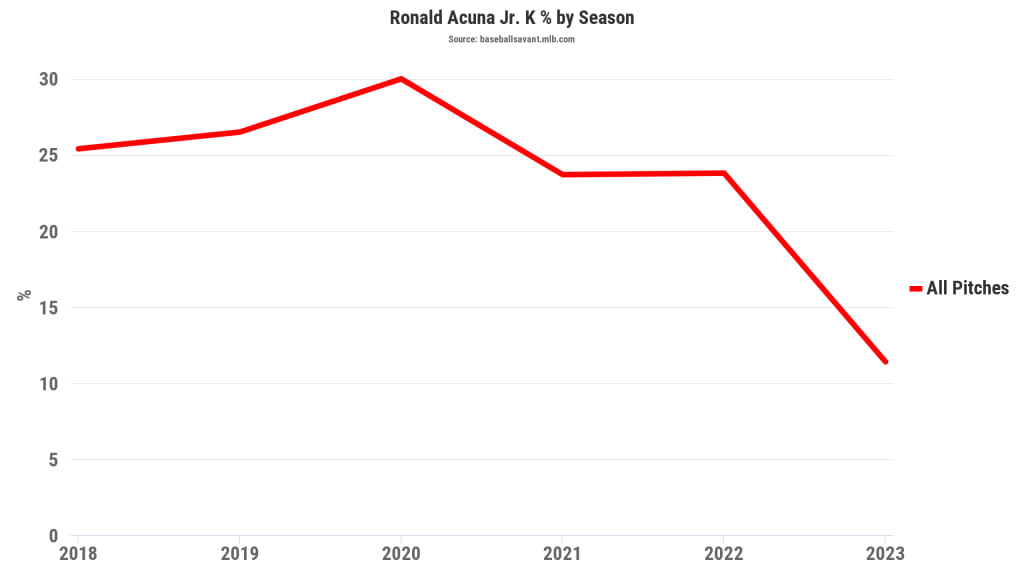

For the first five seasons of his career, Acuña struck out between 23% and 30% of the time he came to the plate, which is slightly higher than average, but nothing out of the ordinary for a power hitter in today’s game. Last year, it was 23.6%, exactly the same as it had been in 2021.

Yet this year, he’s down to striking out just 11% of the time, sixth-lowest rate in baseball entering Tuesday. He’s cut his strikeout rate by more than half, and without the associated drop in power you often see when a hitter prioritizes contact. Acuña is striking out less than Nico Hoerner or Masataka Yoshida. All of a sudden, he’s making contact like he’s choked-up-on-the-bat-going-all-out-for-contact Jeff McNeil, except he’s doing it with 216 more points of slugging.

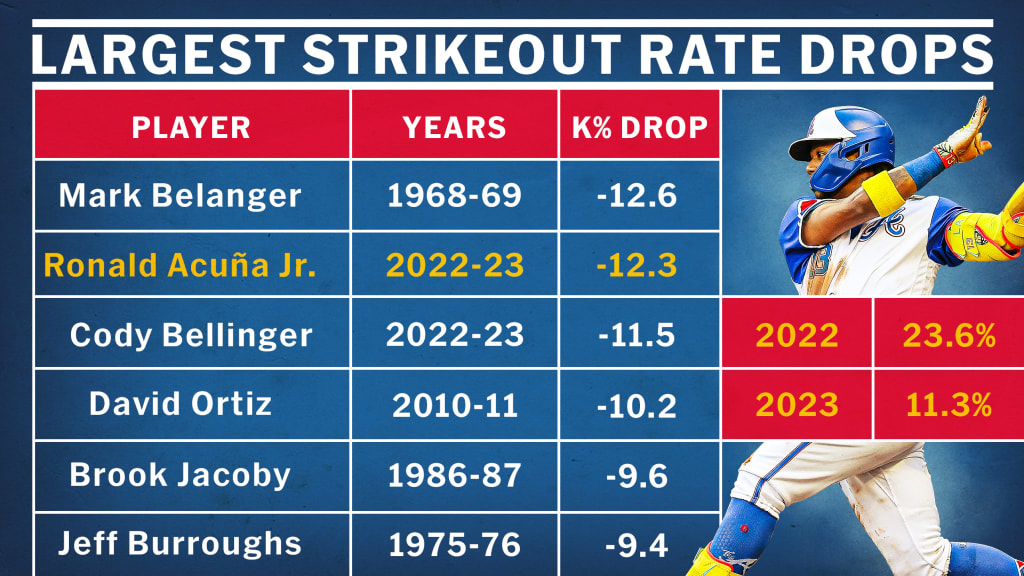

It’s such an impressive drop from last year – it's down by half! Who does that?! – that it felt like it had to stand out historically, and as it turns out, it does. In the history of AL/NL ball, among the thousands and thousands of seasons where a batter had two consecutive seasons in which he qualified for the batting title, there’s only one larger drop in strikeout rate, and it came decades ago.

“Now when he strikes out,” Atlanta hitting coach Kevin Seitzer said when asked recently about Acuña’s season, “it's like we're going, 'What the heck, how come he struck out? He never strikes out.’”

There are caveats all around, of course. Belanger’s drop came after rules were changed following the “Year of the Pitcher” to increase offense. Acuña’s feat has to come with a disclaimer as well, in that it’s pretty hard to cut your strikeout rate if you didn’t first strike out a lot already – that is, it’s not exactly fair to ask Luis Arraez or Steven Kwan now, or Tony Gwynn in the 1980s, or Joe DiMaggio in the 1940s, and so on, to cut an already-miniscule whiff rate even further.

So there’s that, but what he’s done in the context of today’s game still stands out – and there is, incredibly, this: The month with Acuña’s highest strikeout rate this year was April, and it kept on dropping. Now, in September, he’s managed to whiff in just 8% of his at bats (MLB seventh-lowest rate this month) – while also slugging .727 (the fifth-best). He's continuing to whiff less and hit for more power while he's doing it.

But how? That’s the tricky part.

You’d think, perhaps, that Acuña is swinging less. (Not really, in a meaningful way.) You’d definitely expect that he’d be chasing outside the zone less often. (Yes, but only a little.) Maybe he’s watching fewer called strikes go by. (Nope; it’s exactly as often as last year.)

Instead, it’s as simple as this: When he swings, he misses less than he used to.

That’s it. His contact rate is 84%. Last year it was 77%. When he swings in the zone, he’s making more contact, with 86% being up from 80%. When he swings outside the zone, he’s making more contact, with 68% being up from 60%. No matter where the ball is, he's just getting wood on it more often.

“He's always had real good strike zone discipline,” as Seitzer noted, “but he's had a lot of swing and miss in certain areas.”

That backs up the data, and it’s easy to see exactly where it’s happening. Against offspeed pitches, his swing-and-miss is unchanged. Against breaking pitches, his swing-and-miss rate is down a touch. But against fastballs, it’s down enormously, from 23% to 14%.

“[In the past, he’s had a] tough time with high fastballs, you know, he's had some places where pitchers could go if they could get it there that he was vulnerable,” said Seitzer.

That’s not so true this year, as Lance Lynn found out when he tried to hit the top of the zone on Aug. 31. Four hundred and twenty-nine feet later, it was a grand slam to the Dodger Stadium bleachers.

It’s also not just about getting hits on those high fastballs. Sometimes, it’s just about not getting beat, even if it doesn’t immediately turn into a hit. What we mean by that can be seen in the following set of videos, the first two of which assuredly will not end up on any of the numerous highlight reels that will recap Acuña’s incredible season.

Back in June, having already led off the game with a first-pitch homer on a fastball low in the zone, Acuña engaged in a nine-pitch second-inning battle with Minnesota’s Joe Ryan, best known for his invisible fastball delivered from a low release point. Five of those nine pitches were four-seam fastballs, up.

Acuña swung through the first one but managed to work the count to 2-2. Ryan went up with the four-seamer, looking for that high strikeout.

After a splitter in the dirt pushed the count full, Acuña fouled off an inside splitter, and Ryan went back upstairs.

Unable to put Acuña away with his high fastball, Ryan went back low with a splitter. It didn’t end well.

What this shows is that on fastballs along the high edge of the zone, Acuña has turned whiffs into fouls. After fouling off 38% of swings at those high fastballs last year, it’s 49% this year; at the same time, after swinging through 44% of those high fastballs last year, it’s down to 33% this year. A foul doesn’t put a run on the board, but it keeps you from walking back to the dugout until you get a pitch you like better, too.

So: Can it really be all about health? After all, it’s not like Acuña was striking out at Kwan-like levels prior to the 2021 knee injury that interrupted his career. Seitzer pointed out physical impact, saying “it comes back to the health aspect where his lower half is firing the way it's supposed to, which makes him not have to force it so much with his upper body,” but he also made an interesting point about experience -- or the surprising lack of it for a player now in his sixth Major League season.

“Really, you look at it, it's been a long time since he's been completely healthy and had a full season, you know?”

It can be argued that Acuña had only had one previously healthy full season, back in 2019, given that 2020 was a shortened year, 2021 was the injury, and 2022 was, by all indications, a somewhat tentative return to the field. Acuña is simultaneously a veteran of more than 3,000 Major League plate appearances and a player young enough that he was younger than several of the players who received votes in last year's Rookie of the Year balloting. Not only has it been a long time since we've seen a full year at full health, but a lot of roadblocks have been thrown into his developmental process.

“Last year, he wasn't healthy. This year, he's ultra-healthy and he's playing with confidence that we haven't seen for a long time,” Seitzer said. “It's been ultra-impressive.”

It’s hard to disagree.

MLB.com’s Mark Bowman contributed to the reporting of this article.