The cab pulled up to Yankee Stadium around 11 a.m., more than eight hours before Jose Contreras was scheduled to throw the first pitch against the Devil Rays.

Just two days shy of his 26th birthday, Sam Marsonek stepped out of the car and made his way toward the ballpark. He had dreamt of this day since he was a kid, before his path to the Major Leagues took him through places from Port Charlotte, Fla., to Pulaski, Va.

“I thought from a young age that I was going to be the best,” Marsonek said. “From the time I was 12, I wanted to break Nolan Ryan’s strikeout record. I was one of the top high school arms, so I thought I had a good chance.”

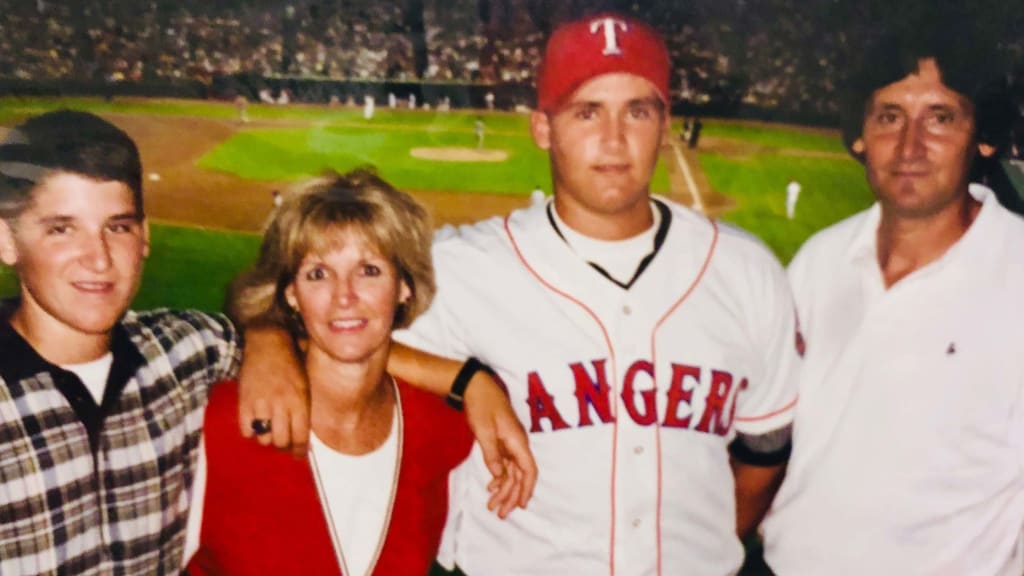

It was July 8, 2004, and Marsonek had finally arrived in the Bronx. A first-round Draft pick of the Texas Rangers in 1996, Marsonek had endured his share of adversity -- most of it self-inflicted -- throughout his first eight pro seasons, but it was all worth it now that he was inside Yankee Stadium, his pinstriped No. 60 jersey waiting for him at his locker.

“I didn’t want them to change their mind,” Marsonek said of his aggressively early arrival that day. “I just walked around the stadium, seeing Monument Park. I walked into Joe Torre’s office -- he was one of the first guys that got there -- and he said, ‘Welcome to New York. As long as you can throw strikes, you’ll finish games that Mariano doesn’t have to come in and close.’”

A couple hours later, Mariano Rivera walked over to welcome Marsonek to the Bronx.

“He smiled and said, ‘Sammy, you’re finally here to take my job,’” Marsonek recalled. “It was awesome.”

To understand the emotions Marsonek felt that day, you must first appreciate the journey he had taken to get there.

Great expectations

Like most first-rounders, Marsonek had all the promise in the world as he embarked on a pro career straight out of Tampa’s Jesuit High School, a program that has produced a dozen other Major Leaguers, including Lou Piniella, Brad Radke and Lance McCullers Jr.

His first season in the Rangers organization did not go well. The 6-foot-6 right-hander posted a 5.29 ERA between the Rookie and Class A Advanced levels, experiencing the first struggles of his baseball life. Before long, he began to drink to help him cope with his new reality.

“Right away, I realized I wasn’t who I wanted to be,” Marsonek said. “I didn’t know how to deal with it. Initially, it was just a way to escape and, really, to sleep. That’s how much I loved the game; it had taken control of my life. How I was doing on the field dictated what I was doing off the field.”

A strained ligament in his arm limited him to 11 2/3 innings in 1998, and 1999 saw him pitch to a 5.54 ERA at Class A Advanced. The Rangers, it seemed, had given up on the 20-year-old.

“I got labeled as a drinker who couldn’t control himself off the field,” Marsonek said. “I didn’t feel like there was much help out there.”

That all changed when the Yankees traded for him in December 1999.

“Going to the Yankees, a lot of guys with troubled pasts have seen their careers resurrected, so I was just looking for a new opportunity,” Marsonek said. “I felt extremely encouraged there. Guys like [farm director] Mark Newman really poured into me. I got to start over again.”

The Yankees years

Marsonek’s performance on the field improved during his first three years in the Yankees organization, but it was his move to the bullpen -- one he wasn’t fond of, initially -- that sparked his career. He made the International League All-Star team in 2003 and ’04. But even with success on the field, his drinking continued -- as did a handful of brushes with the law, which included three DUI arrests.

When Marsonek was called into Triple-A Columbus manager Bucky Dent’s office on July 7, he assumed he had been traded.

“They sat me down after BP and said, ‘Pack your stuff. You’re headed to New York,’” Marsonek said. “It was a very emotional time for me considering everything I had gone through over the past eight years. It was surreal to finally get the call.”

Marsonek watched his first three games as a big leaguer from the bullpen. The Yankees won all three, with Rivera earning the save in each victory. On, July 11 -- one day after Marsonek’s 26th birthday -- New York held a 9-3 lead with two outs in the eighth inning when Torre signaled to the bullpen, summoning Marsonek to take over for Felix Heredia.

“I don’t remember feeling anything in my body,” said Marsonek, who had family and friends in the stands for his debut. “I felt like I was in the clouds. The run from the ’pen to the mound felt like a mile. I don’t remember feeling the ball, but I wasn’t nervous. It felt right.”

Julio Lugo doubled, but Marsonek got Damian Rolls to fly out to end the inning. Gary Sheffield went deep in the bottom of the eighth to make it 10-3. Then Marsonek worked around a leadoff single by Toby Hall in the ninth, retiring Geoff Blum, Carl Crawford and Rocco Baldelli to end the game.

His final line: 1 1/3 innings, two hits, no runs.

“I got to finish a game,” Marsonek said. “I didn’t give up a run. We won. It was awesome.”

The All-Star break was set to begin the day after Marsonek’s debut, and while he would have preferred to remain in New York, his teammates were all scattering after that Sunday game, so he flew home to Tampa to spend a few days before the team gathered in Detroit to open the second half.

“I caught a flight home and never got back,” Marsonek said.

During a day fishing and drinking with his brother and a friend, Marsonek wiped out on a wakeboard, badly injuring a knee. When he awoke the following day, he could barely walk. He called general manager Brian Cashman to inform him of the situation, though he told the team he had slipped on a dock rather than revealing the true nature of the injury.

“I made a bad decision. A strap on the board came undone, and I blew out my knee,” Marsonek said. “I never felt that low. For all the Yankees had done for me, I felt like I let them down more than anyone.”

Rather than having surgery to repair tears in his meniscus and MCL, Marsonek rehabbed the injuries in an attempt to get back before the end of the season. He appeared in some Minor League playoff games but never made it back to the Majors that season.

“I got back on the field as quick as I could,” he said. “I don’t know if it ever really healed the right way. It still bothers me.”

A long, strange trip

A healthy Marsonek returned to big league camp in 2005, but he didn’t pitch a single inning all spring, instead serving as a backup pitcher for every road game.

“Not that I didn’t deserve it,” he said, “but I kind of knew it wasn’t going to happen again with them.”

Sent to Triple-A at the end of camp, Marsonek’s season spiraled out of control. He posted a 6.61 ERA in 49 appearances, the worst of his career. His failure on the field made him reassess his actions away from it, but every time he tried to make a positive change in his life, his demons would reappear.

“When you had as many DUIs as I had, other arrests, a career in jeopardy, most people would try to stop,” Marsonek said. “I had tried to stop a lot, but I couldn’t stop. I’d go maybe a week, then fall right back into it.”

Andy Phillips, a longtime teammate of Marsonek and a devout Christian, requested to be Marsonek’s road roommate for the second half of the 2005 season, hoping to be a sounding board for his friend.

“I wanted to love on him a little bit,” Phillips said. “I just saw a guy who was searching to find who he was. The things that he was doing, the life he was living, was destructive. I think he felt like if he just did a few things better, it would fix it -- and it actually got worse.”

As the season neared its end, Phillips invited Marsonek to accompany him on a November trip to the Dominican Republic, telling him they would help out with some youth clinics and play some golf.

“Out of obligation and guilt for what I had put him through, I told him I would go,” Marsonek said. “It was a mission trip. I was flying out of Tampa, coming off a three-day binge with no idea what I was getting into.”

Working with hundreds of Dominican kids, many of whom didn’t have gloves, shoes or even pants, served as an eye-opener for Marsonek. Teammates, including Robinson Canó, had grown up in the area, overcoming the odds to become big league stars. Marsonek had taken it for granted from a young age that he would play in the Majors, and although he had an all-too-brief taste of that dream, seeing these children play the game for nothing more than sheer love of the sport resonated with him.

“Something just clicked,” Marsonek said. “I started to think about my life and their lives. Take away the game from them and they had nothing; take away the game from me, what did I have? Who was I? Those were questions I had never had to think about before. I was a pitcher who was going to get back to the big leagues, but that was all in question now. I’m 27 years old and had never thought of anything else since I was 10.”

Later that night, Marsonek listened to a pastor speak.

“I don’t remember what he said -- I just remember that while he was speaking, I could not breathe,” Marsonek said. “The last thing he said was, ‘If your pain is greater than your fear of change, then you’re ready.’ It took me a while to understand it. It’s hard for most everyone to understand, but I was going through pain because the game was about to be over.”

Marsonek gave up drinking that day.

“I think Sam had clarity for the first time in his life that everything had been chasing, he'd been chasing in the wrong direction,” Phillips said. “It didn't take long for you to be around him to see that this wasn't the same guy. His level of immaturity and the shallowness of his life was gone.”

Marsonek’s baseball career wasn’t over yet, but it was winding down. He signed a non-roster deal with the Cubs in 2006, but he blew out his shoulder in his first live batting practice session. Marsonek worked his way back from shoulder surgery, pitching in the independent Atlantic League in 2007, earning him a shot with the Nationals the following spring.

When he was released on the final day of camp in 2008, he knew his career was finished.

The aftermath

Marsonek coached high school kids for a few years after he retired and later worked with a ministry called SCORE International to put together youth travel teams in the Tampa area. Players came from Florida, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, the Bahamas and Canada. One of his first teams in Tampa even included White Sox star Eloy Jiménez.

“We lost in the state finals that year,” Marsonek said. “I told them after the game, ‘I would never trade this for another day, month or year in the big leagues.’ To that point, my life had been all about me. Every decision I had made was for me. This was about others, and it felt so much better.”

Marsonek also owned a couple of automotive shops in the area, and his wife, Kristen, is a physician. In 2016, SCORE purchased a baseball facility in Greene County, Alabama, called Baseball Country. Marsonek agreed to move there to run the facility, which works with travel players, local kids and pro prospects alike.

Three years later, the Marsoneks bought Baseball Country from SCORE. Summers consist of travel teams that train and compete in multiple tournaments, while the other nine months are filled with retreats and team camps that focus on team building and personal development.

“I thought it was going to be just a place to train players,” Marsonek said. “It’s become so much more than just a baseball facility.”

Marsonek uses his own experiences -- both the positive and negative -- to help teach the kids that make their way through Baseball Country. He even has worked with professional players, some of whom are sent to the facility by their agents or clubs if they’re experiencing their own struggles on or off the field.

“That’s what fuels a lot of what I’m doing now -- mistakes and regrets,” Marsonek said. “Baseball is all temporary; it’s cool to help a kid get a scholarship or get drafted, but it’s ultimately about trying to help them identify who they are as a man.”

Sam Marsonek is one of 11 players featured in Jacob Kornhauser’s new book, “The Cup of Coffee Club: 11 Players and Their Brush with Baseball History” (Rowman & Littlefield publishers). It is available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound.org.