Spring Training and the warm, sunny climates of Florida and Arizona are a match made in heaven. It's clearly the best way for teams and players based in northern cities to escape the winter and get ready for the upcoming season -- and maybe pick up a nice tan along the way. Like peanut butter and jelly, Spring Training and a warm climate is a pairing that, once discovered, no one would ever dream of breaking apart.

It's sometimes hard to comprehend while watching games with palm trees and cacti in the background in February and March, but baseball can be affected by the world around it. The most common example, of course, is games getting rained out. But, for large scale nationwide or global events, the entire sport feels the impact. And, for three years from 1943-45, the United States' involvement in World War II forced baseball to remain north for Spring Training.

Fighting a World War required a lot of resources. Items that were needed overseas -- such as canned goods, gasoline and meat -- were rationed at home to ensure there were enough for the war effort. Beyond that, the U.S. government encouraged regular civilians to do their part by planting Victory Gardens to grow their own food.

In that same spirit of cutting back at home to fight the war abroad, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, in coordination with the U.S. government's Office of Defense Transportation, restricted Spring Training travel starting in the 1943 season. With train lines moving troops around the country and the need to conserve resources, teams were instructed they couldn't go south. Specifically, they would have to find sites north of the Ohio and Potomac and east of the Mississippi River to prepare for the upcoming season -- the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns were given exceptions and allowed to remain west of the Mississippi to train near home in Missouri.

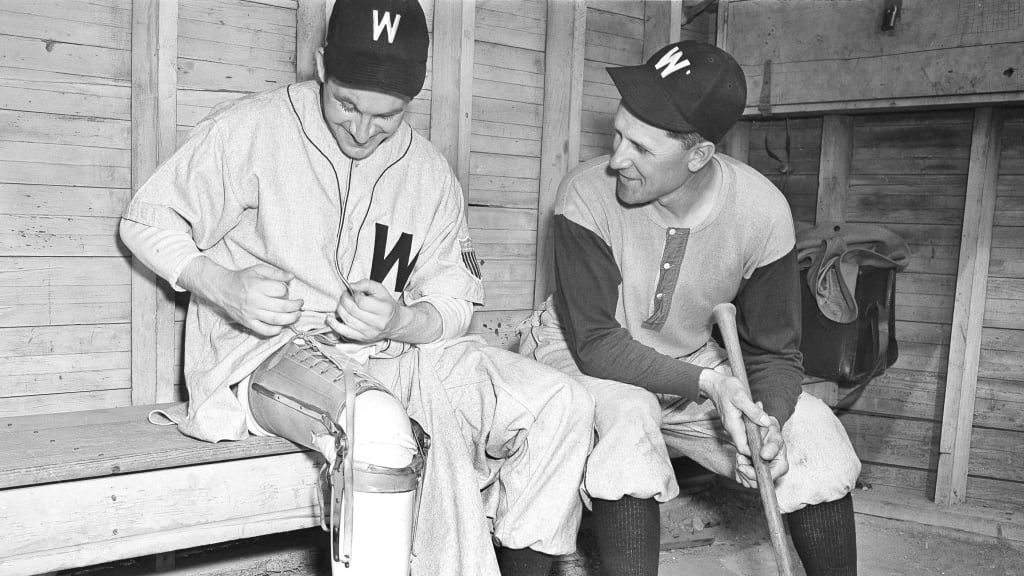

Unsurprisingly, most teams were not prepared with contingency plans to conduct Spring Training in non-southern locales. The announcement that teams would have to stay close to home before the 1943 season set off a mad scramble within each club's front office to find a suitable facility. The Washington Senators checked out what Georgetown and Catholic Universities in D.C. had to offer before settling on the University of Maryland's digs just out of town in College Park, Maryland.

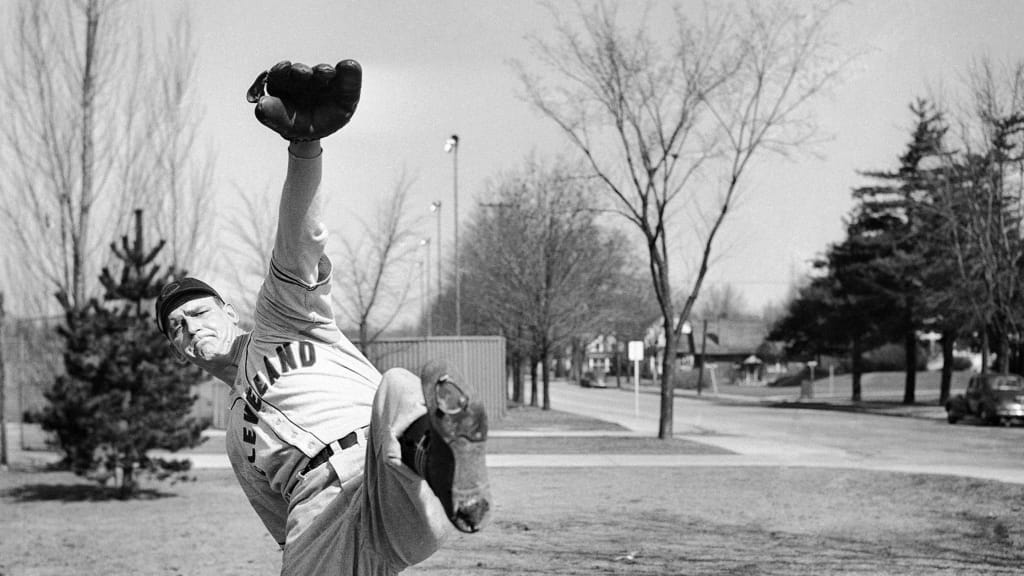

A number of teams found themselves at local schools. The Red Sox trained at Tufts University outside Boston, and the Indians went to Purdue University because Indians general manager Roger Peckinpaugh deemed their recently-built field house as "the last word in field houses."

“It has an earth floor large enough to lay out a football field," Peckinpaugh described. "And we could hold infield practice there as readily as outdoors.” If you forget that there's no sun and that it's a college field house, it sounds splendid.

Of course, communities also got in on lobbying teams to pick them. Frederick, Maryland was one such town: The Frederick Chamber of Commerce pitched their McCurdy Field as a suitable venue. The Philadelphia Athletics held their 1943 Spring Training in Wilmington, Del., but toured Frederick alongside members of the Chamber of Commerce prior to 1944 and selected the site a day after the tour.

The common factor in selecting a site: an indoor facility conducive to baseball. There's a reason teams flock to the south for Spring Training: The weather in cities like Boston, New York and Chicago isn't exactly conducive to baseball in March.

Teams tried to put a positive spin on what was obviously an inferior situation. Gone was the hassle and ordeal of traveling for hours to find warm weather. The Washington Post described the Senators' journey to Spring Training: “The Nats eight-mile trek to spring training camp was very un-thrilling. The athletes assembled at Griffith Stadium in the morning, piled into cars, hit the back road to College Park, and 15 minutes later were being shown to their rooms on the University of Maryland campus.”

The Cubs and White Sox had to travel a bit farther to their 1943 spring home in French Lick, Ind. -- just under 300 miles -- but still much closer than where they had been training in California. Combined with the fact that these wartime camps didn't last as long, the shorter travel figured to reduce costs greatly. The Chicago Tribune even predicted that those savings could cause teams to keep training in the north even after the war ended.

Athletics manager Connie Mack felt similarly. “Personally, I don’t think we’ll ever again put in six or seven weeks way down South," he said in March 1944. "When it comes right down to it, it’s the individual; any player can get into condition in any climate if he decides to do so. No doubt it would be a little better to train in a warmer climate, but I can’t see that it makes a great deal of difference.”

This sentiment, as we'll clearly see, was not entirely in accord with reality.

One problem teams immediately encountered at their new spring homes had less to do with the new digs and more to do with the larger war effort. Namely, all their players were serving in the war.

Well, not exactly all of them, but certainly enough to be noticeable. The Red Sox's first workout at Tufts in 1944 featured more members of management (six) than players (four).

Branch Rickey and Leo Durocher transformed the Dodgers' Bear Mountain camp into a de facto tryout for the team. While many of their veteran players were overseas, Dodgers camp was populated by teenagers too young to get drafted into the war.

It was also an opportunity for veterans to prolong their careers, especially those who were classified as 4-F -- unfit for military service. In order to field a team during the war, owners and managers were going to have to lower their standards for players. Even Durocher -- a "player-manager" who hadn't played a full season since 1938 -- gave fielding a shot despite bad knees and bone chips in his elbow.

A lack of players wasn't the only problem facing teams during these years of northern Spring Training. They were also trying to play baseball and get ready for the season in the midst of winter. And winter didn't really care.

By selecting facilities with ample indoor space, teams clearly and rightly anticipated sub-optimal baseball weather. But, the country wasn't flush with indoor ballparks and these indoor spaces were mostly college gymnasiums. This limited the range of activities and drills teams and players could do to get truly ready for the season.

These indoor practices also didn't seem as focused as we think of now with players stretching and going through drills in unison. On a human level, that's understandable. Looking around some college gym at a war-depleted roster with winter raging outside the doors likely didn't do wonders for morale. When weather forced them to practice indoors at their shared hotel in French Lick, Ind., -- which was often -- the Cubs and White Sox had their infielders and outfielders train in the auditorium while pitchers and catchers worked out in the room next to the auditorium with an improvised dirt stage and a backstop made of hotel mattresses.

The conditions were bleak, but some teams appear to have made the best of it. The Yankees trained in Atlantic City in 1944 and '45 -- they spent '43 in Asbury Park -- and held a contest where they tried to hit the 137-foot high ceiling. The Senators' indoor sessions at the University of Maryland are said to have involved more basketball than baseball drills.

It was the exhibition games where the fun really started. It goes without saying that an actual baseball game can't be relocated to a college gymnasium or a hotel auditorium if the weather becomes hostile. The Dodgers staged an amusing photo of Branch Rickey and the team groundskeeper attempting to dig out home plate at Bear Mountain, but it reveals a truth: Snow was a constant issue.

In 1944, the town of Frederick declared a half-day holiday so fans could take in a game between the Athletics and Yankees -- the only exhibition the A's played against another Major League club. The encouragement worked as 1,500 fans showed up. Unfortunately, the weather had other plans. It started snowing in the fourth inning, but play continued and the snow eventually stopped. In the eighth inning, it came back with a vengeance, reaching blizzard-like conditions. The umpires were forced to cancel the game and it was never resumed. Such was Spring Training in the north.

But the best story comes from Cardinals camp in Cairo, Illinois. Along with the Browns, the Cardinals received special permission to host Spring Training west of the Mississippi. Despite warnings of the town's history of spring flooding -- it is located where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi -- things worked out pretty well for their first two seasons in town. Sure, they probably experienced the baseline level of discomfort every other team faced and there was that diphtheria outbreak in 1944, but at least they avoided the flooding and won NL Pennants in 1943 and '44 and the World Series in 1944.

Luck turned in 1945. When the team showed up in Cairo, they discovered that the banks of the Mississippi had flooded and the field was unplayable. The town did everything to get the field in shape from digging ditches to using fire pumps, but each day they arrived at the park to find it flooded once more.

At one point, the water in the outfield was four feet deep, so pitcher Max Lanier, first baseman Ray Sanders and third baseman George Kurowski grabbed their fishing poles and went fishing in it. It was at that point that team management decided it was time to return to St. Louis.

With the war ending in 1945, teams returned to warmer climates for Spring Training in 1946 and, to no one's surprise, players responded positively to not being forced to play baseball out in the cold or inside dusty old gyms. According to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the Indians were in better shape after two weeks in Florida than they were at the same point during any of their years in Indiana.

Spring Training baseball has remained in the south ever since and, based on the results of this three-year trial run in the north from 1943-45, it would probably be a good idea to keep it that way.