There’s absolutely no shortage of legendary home runs in baseball history, whether we’re talking about Babe Ruth’s “called shot” in 1932, Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” in 1951, Carlton Fisk’s foul-pole prayer in 1975 or thousands of others along the way. Homers make up something like 3% of plate appearances, yet it feels like they comprise about 80% of incredible baseball moments.

Some exist only in memories, or in print, or on grainy video. Others have plaques or other memorials installed to mark the location.

But only one is so memorable that all you have to do is say "the red seat" and know that people will immediately know what you mean. In the deepest part of right field at Fenway Park, seat 21 in row 37 of section 42 is painted bright red, standing out amongst an endless sea of green. It's such a Fenway landmark that it's even visible on the official seating chart when fans buy tickets from RedSox.com.

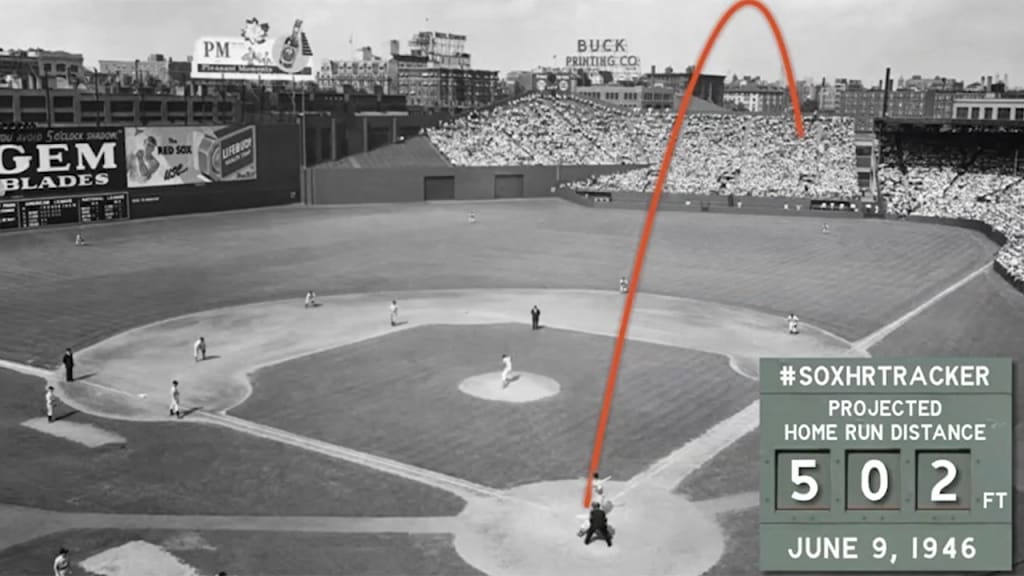

It’s where Ted Williams hit a ball that went a reported 502 feet back on June 9, 1946, and ever since it was painted red in 1984, it has served as a target for left-handed hitters trying their best to measure up to one of the greatest pure hitters who ever played.

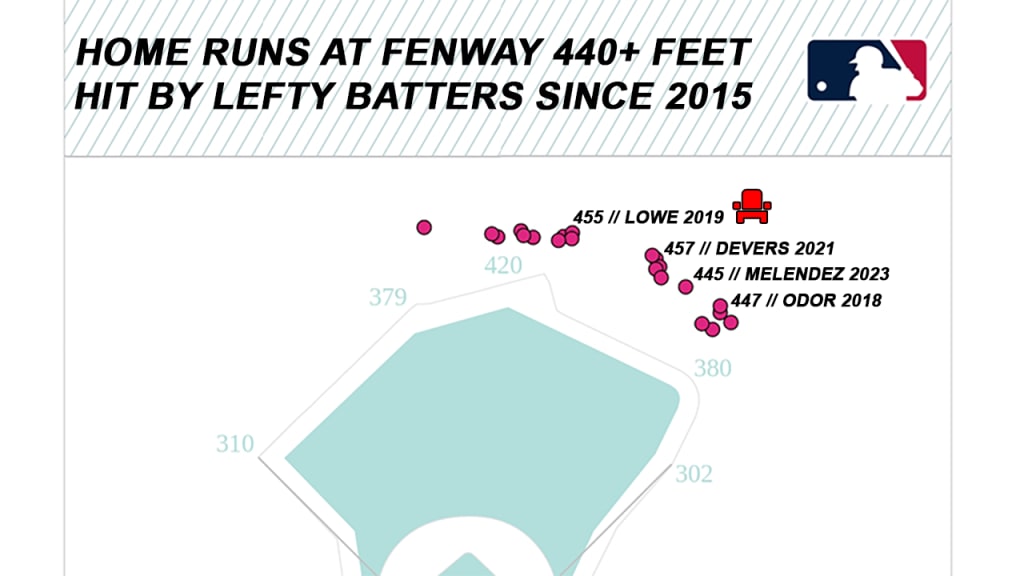

No one, however, has done it in all the years since. No one, it seems, has come even close, to the point that hitters regularly call the location and/or measurement of the seat into question. How, after all, could no one in the ensuing three-quarters of a century manage to come anywhere near the Splendid Splinter?

In 2016, no less a slugger than Hall of Famer David Ortiz expressed disbelief that it was even possible, saying “you see how strong ballplayers are today ... and I’m not saying Mr. Ted Williams wasn’t … but you see how far guys are hitting balls today, and none of them can do it.” (He even once reportedly tried, unsuccessfully, to get there in batting practice with an aluminum bat.) It was a similar tale from 1990s lefty masher Mo Vaughn, who once noted to the Boston Globe that “it's hard to believe anybody could hit a ball that far. I know I've never even come close -- not even in batting practice.”

Earlier this month, present-day lefty power bat Triston Casas stirred the pot back up again when he echoed his predecessors, suggesting that “[the] Ted Williams seat is starting to feel more and more like a myth” and that “it’s looking more and more out of reach as I hit balls better toward that direction,” requiring manager Alex Cora to step in to defend his young first baseman. “He was giving [Williams] a compliment,” said Cora, “to be honest with you.”

Even occasional visitor Miguel Sanó got in on the action when he was in town with the Angels this month, looking back upon the ball he blasted at 495 feet in 2021 and saying “mine I think is longer than that one, I think so 100%," adding that “you already know who hit it over there so I don't think they'll give it to me, but I think my homer was farther."

All of which raises the question: Is it even possible that Williams hit a ball that far, that many years ago, when no one has done it since? Or was he the beneficiary of some -- let’s say -- “friendly home scoring,” meant to benefit a franchise icon and keep a legendary myth alive?

After all, sluggers keep insisting Williams couldn’t possibly have hit it there, sensibly arguing that it’s all but impossible to think that no one as strong or stronger than Williams could have come through in the last eight decades. “I tell [players who ask about the red seat], ‘They say Mr. Ted Williams hit a ball out there,’” said Ortiz back in 2016. “And they’re like, ‘Yeah, right.’”

So: Could he have really done it? And what does it really mean to have hit a ball 502 feet, anyway? This play may have happened 78 years ago, but we can use some modern-day technology to investigate. Spoiler alert: Williams didn’t hit his ball 502 feet. He (almost certainly) hit it farther.

Since this topic keeps coming up, it’s worth noting that it's already been looked into more a few times over the years. We’re partial to Alex Speier’s look in the Boston Globe a decade ago, and back in 2006, home run tracking expert Greg Rybarczyk -- who would later spend a decade as a Red Sox analyst -- did his own investigation as well.

It goes without saying that little has changed about the story since their investigations, but advances in baseball technology have been astronomical since then. At the time Rybarczyk wrote, there wasn’t even reliable pitch tracking. When Speier wrote, Statcast was barely half-a-season into its existence.

Ten seasons on, the technology has been upgraded more than once, added the ability to capture weather data, and each ballpark has been scanned down to the inch. Since 2015, Statcast has tracked nearly 50,000 home runs, and only three of them have been projected at 500-plus feet. No lefty has even managed to hit a ball in Fenway 460 feet, making tall tales like Mickey Mantle’s supposed 565-foot home run seem like exactly that, and making Ted’s 502 seem implausible.

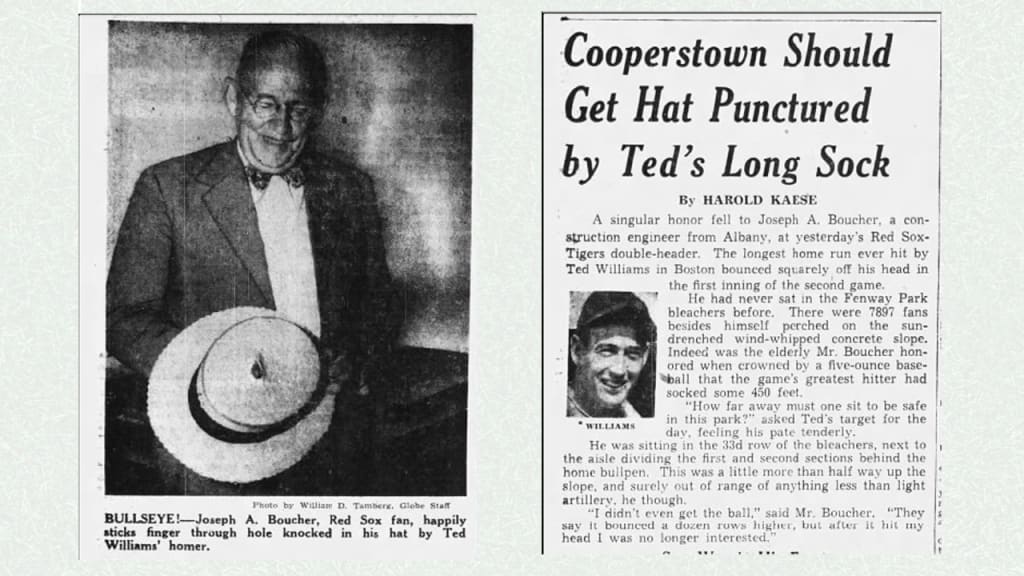

We don’t have any video of the play from 1946, unfortunately, which adds to the myths and legends here. But we also might not need it, because the landing spot of the ball is one thing that is not in question. As Harold Kaese (himself a legend in his field) wrote in the Globe the next day, the unfortunate patron sitting in seat 21 – which was a backless bleacher seat in those days – earned himself a trip to the doctor (and a nice hole in his hat) for his trouble:

A singular honor fell to Joseph A. Boucher, a construction engineer from Albany, at yesterday's Red Sox-Tigers double-header. The longest home run ever hit by Ted Williams in Boston bounced squarely off his head in the first inning of the second game.

“The ball struck the very center of the crown,” added Kaese, “a perfect bullseye. It made a tidy little hole that speaks well for the quality of the headspiece.”

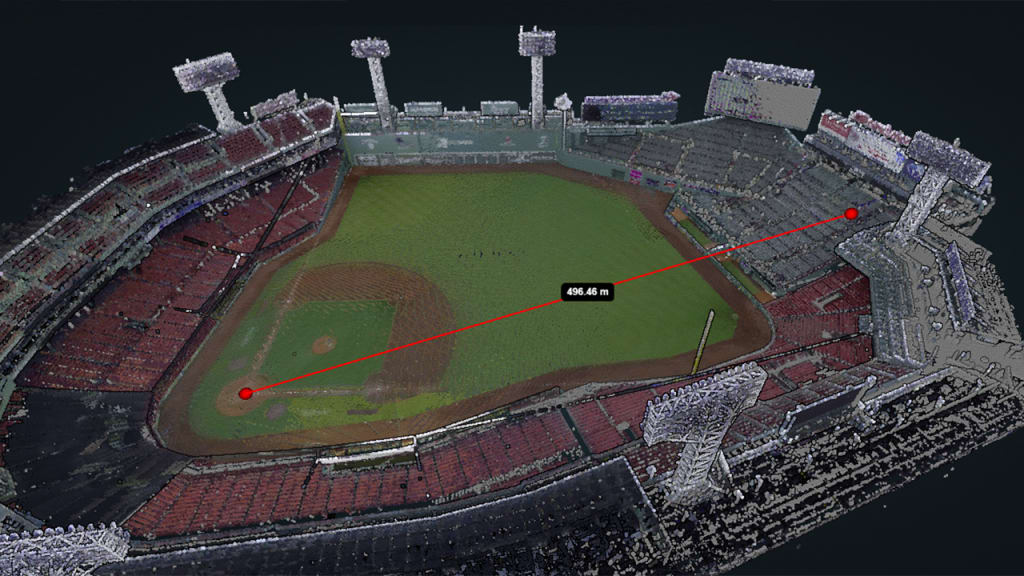

Haberdashery standards aside, that bit of information remains tremendously useful all these years later, because seat 21 in row 37 remains exactly where it was in Williams’ day, just now with a seatback. Since each Major League park has been scanned via lidar (a form of laser measurement that allows for precise calculation of distances), that means that we can measure the exact distance from home plate to Boucher’s seat. When we do that, we get 496 feet.

Right away, this explains some of the confusion, and it’s nothing more complicated than “there’s more than one way to measure a home run.” When the Red Sox claimed that Williams’ blast went 502 feet -- after initially claiming 450 feet, it should be noted -- they were almost certainly measuring that distance from home plate to the impact point, and we’re willing to chalk up the difference between their 502 and our 496 to the difference in 1946’s best estimates to 2024’s more precise measurements.

Either way, that’s not how home run distance is measured today. Instead, distance is projected all the way back to the ground. That was the chosen method in part because of places like Fenway Park, where two identically hit balls over the Green Monster shouldn’t have a difference of dozens of feet of distance, just because one clanked off a light tower and the other managed to sneak through onto Lansdowne Street.

For example, when Casas hit the blast that stirred his comments, it was measured at 429 feet into the bleachers. But what that really means is that the impact point was 421 feet away, and given the speed and angle of descent, it was projected to have gone eight additional feet before returning to ground level.

So by today’s measurement standards, Williams didn’t hit his home run 502 feet. He instead hit it something more like 525-530 feet, based on lidar estimates, which for our purposes is both good (it explains why no one has been able to come close since!) and bad (that’s an even harder to believe figure!) Which is it?

Now that we’re measuring on the same scale, there’s primarily two things that could explain a ball traveling much, much farther than you’d expect. The first is the composition of the ball itself, which we’ll set aside since we have absolutely no information to refer to, since the ball bounced through Boucher’s hat, off his head, then was lost to history.

The second is the environment, meaning altitude or humidity or wind, as was the case in Texas on the warm day that Nomar Mazara hit a Statcast-record 505-foot homer in 2019. Not only was it a windy day, but the wind had damaged wind screens in Arlington, which hadn’t yet been repaired and seemed to allow even more airflow to carry the ball farther.

Wind, as Dr. Alan Nathan once found, can add 18.8 feet for every five mph of wind in the right direction. Last season, MLB data scientist Clay Nunnally used Weather Applied Metrics data to look at Jarred Kelenic’s monstrous 482-ft blast in Wrigley Field; that one that gave Cubs broadcaster Jon Sciambi an opportunity to admire a true tater, saying, “Oh my goodness … I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a ball hit there.”

Nunnally’s analysis showed that the ball was pushed an additional 49 feet just by wind, the longest wind-aided push of the season. Over the previous three seasons, balls hit with similar exit velocity and launch angle were hit an average of 440 feet, though with a spread of a few dozen feet in each direction, given the different environmental conditions each of those balls faced.

So yes, wind matters -- and it was windy that long-ago June day in Boston, which is more than a little bit of an understatement.

The ball was “wind-whipped” and “borne on a high wind,” as Kaese wrote the next morning. “A rare and brisk northwest breeze made Yawkey Yard a home-run heaven for southpaw clouters and a couple of right-handers,” as Globe colleague Gerry Moore followed up with the next day.

The Globe’s Sunday headline blared that the “storm disrupts lights, phones, uproots trees,” and alongside Kaese’s front-page story on Monday, the paper ran a story about how electrical storms on Saturday night and ensuing winds on Sunday caused “damage [that was] the worst in 60 years,” and that “fresh westerly winds … added to the weekend casualties by upsetting small boats and causing several drownings,” as well as passing along stories of babies delivered under flashlights at hospitals that had lost power.

If that all sounds like a storm that was created entirely to further a legendary moment, we’d forgive you for thinking we’re describing the clock tower plot of “Back to the Future,” set nine years later. But we can do better than mere anecdotes. We have numbers.

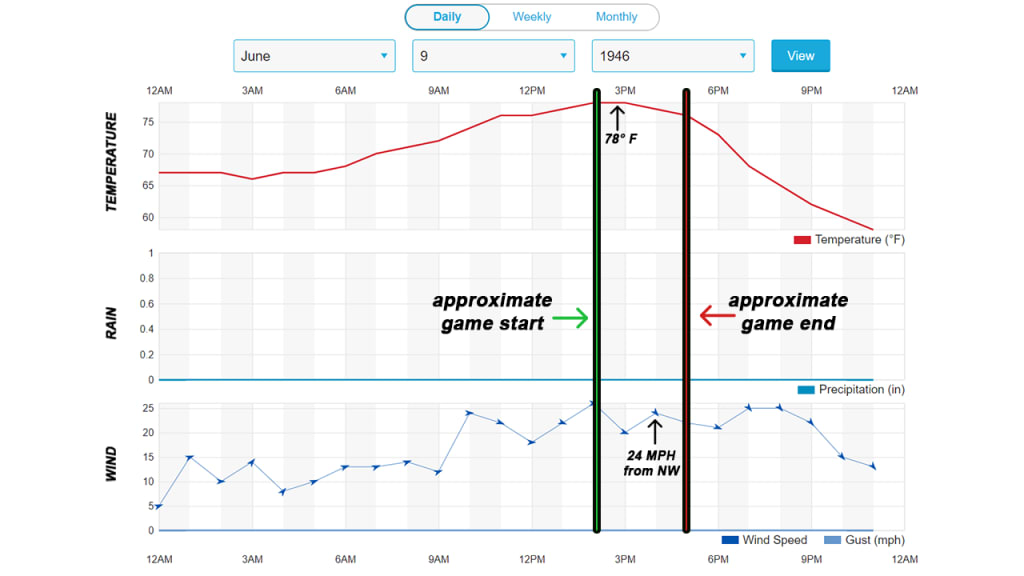

Hourly wind data, believe or not, is easily available even from 1946. While it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment of Williams’ blast, it was the first inning of the second game of a doubleheader in the final year before Fenway Park received lights. We know the first game lasted two hours and six minutes, making it reasonable to think the second was a mid-afternoon start to avoid losing the end of the game to darkness.

While that’s more of a guestimate than an exact time, the story doesn’t really change in that window: temperature in the high 70s, no precipitation, and prevailing winds above 20 mph out of the northwest -- which leaves open the possibility to brief gusts well above that.

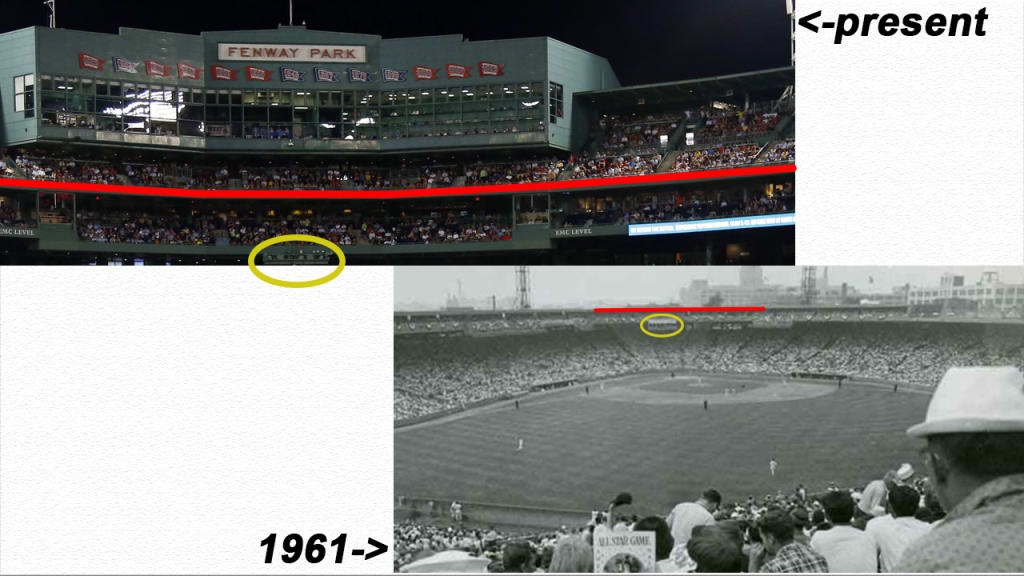

But there’s wind, and then there’s being able to catch the wind, and this is the trick that’s easily forgotten. That famous press box that sits above home plate, the one with the iconic “Fenway Park” sign and the collection of pennants the team has won over the years? That didn’t exist in 1946. It was first added in 1982-83, then renovated in 1989 to add club seating underneath it, then known as the 600 club.

You can really see the difference in this comparison between a shot from 1961 -- note the All-Star Game program in the bottom, and Fenway did indeed host one of the two games that year -- and one taken in 2014. Look how much more exists above that original red line, now.

As Nunnally noted in a presentation given to the SABR Analytics Conference in Phoenix, Ariz., not only was the batter literally Ted Williams in the prime of his career, but Fenway at the time had “what [was] essentially the shortest stadium wind shadow of any Major League ballpark.” As he continued to explain, “Ted’s home run entered the jet stream before it passed first base, [and so,] approximately 90% of this trajectory is spent in unabated wind.”

"Hits with the highest apex can be pushed around,” added Nunnally, speaking more generally about wind and not specifically about Fenway, “changing their landing position by 100 feet or more,” all of which largely confirms the estimates that Rybarczyk made nearly 20 years ago.

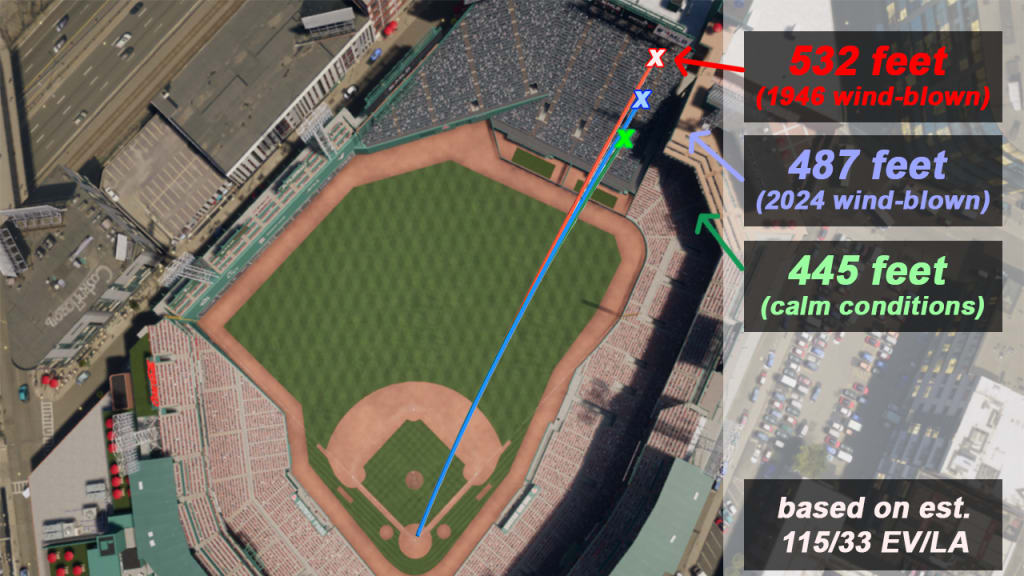

In order to really illustrate this, we took Dr. Nathan's estimates that the ball was hit at 115 mph of exit velocity and 33 degrees of launch angle, then turned to our friends at Weather Applied Metrics to "remove" the top parts of Fenway Park from their model to mimic what it looked like in 1946, thus allowing for the jet stream to be lower.

By inputting what's known about the weather that day -- 78 degrees and 45 percent relative humidity, plus the wind -- along with reasonable estimates about batted ball spin rate and axis, the model suggests that a ball like Ted's hit on a neutral day in Boston might have gone 445 feet. A ball hit like his on an identically windy day in present-day Fenway Park might have gone about 487 feet, showing the effect of the wind.

But a ball hit like Ted's was in 1946, in that weather, in that ballpark? It's reasonable to think we're talking more than 530 feet now.

When Fenway was updated in the 1980s, Red Sox players felt this, even if they didn’t know the science or the math. In 1999, future Hall of Famer Wade Boggs was in the final year of a career that had seen him playing at Fenway both as his home field and a regular visitor for 18 seasons and 854 games. He noted how differently the field seemed to play immediately after the 1989 renovations. “It was obvious,” he said. “The days of the cheapies were over."

Boggs was right, and continues to be; based on Statcast estimates in 2023, Fenway Park was tied for being the park that was the least favorable for the ball carrying, mostly because of cold weather and near sea-level positioning. (Of course, that’s on average; it was nearly 80 degrees on the day Williams hit his shot.)

But it’s not just about “preventing cheapies,” either. It’s about the fact that the conditions that Williams had in his favor, the ones that almost certainly pushed his ball out by dozens upon dozens of feet, just can’t exist today. It’s one thing to have had the good fortune to have hit with a version of a tropical storm at your back, but even with that, 2024 Fenway is simply not the same park as 1946 Fenway -- and that’s not only about the Green Monster seats and the party decks.

“I got just the right trajectory,” Williams told the Globe in 1996, on the 50th anniversary of the homer. “Jeez, it just kept going. In distance, it was probably as long as I ever hit one.”

It almost certainly was. It might have been as long as anyone has ever hit one -- and it might not be possible, Triston Casas is probably relieved to hear, for anyone in Fenway Park to do the same ever again.

Thanks to MLB’s Clay Nunnally, Weather Applied Metrics's Doug Sinton, and Dr. Alan Nathan, Professor Emeritus of Physics at University of Illinois, for invaluable scientific research that contributed to the production of this article.