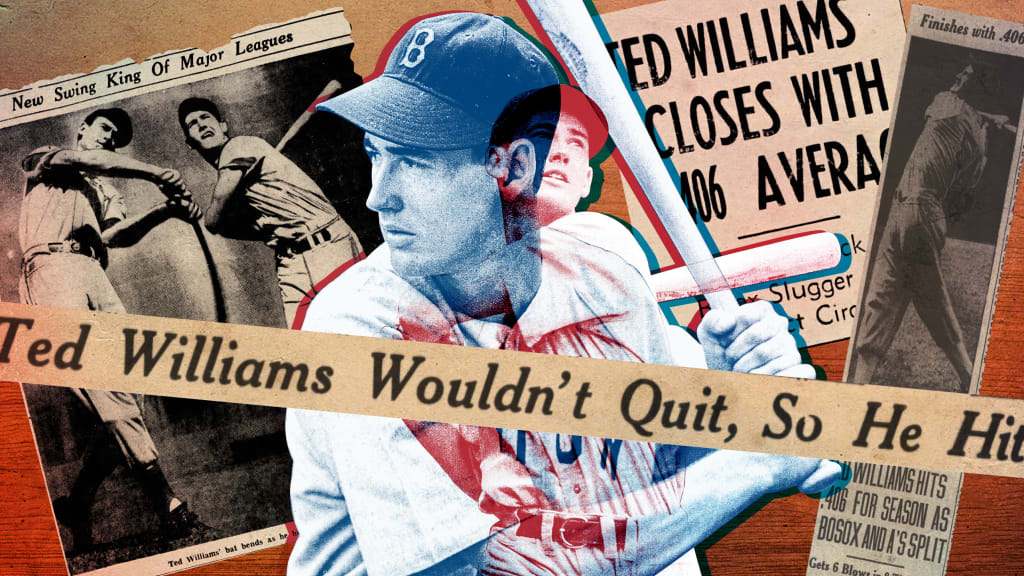

As the story goes, Ted Williams entered the final day of the 1941 season with a .400 batting average and a chance to sit out Boston’s scheduled doubleheader against the A’s, a move that would clinch the first .400 season in 11 years. Instead, the Splendid Splinter played both games, went 6-for-8, and finished with a .406 average, the last time a player in the American or National Leagues finished a season with a batting average that high.

But it’s not quite so simple as a choice between Sit or Play.

First, let’s back it up to the start of the season-ending three-game series in Philadelphia. It was originally scheduled to be a three-day affair, with a game each on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, but A’s owner and manager Connie Mack rescheduled the opening game to be part of a Sunday doubleheader in order to boost attendance with the 22-year-old Williams chasing history. (Sunday was also scheduled to be Lefty Grove Day as Philadelphia feted the 41-year-old Red Sox hurler who had spent his first nine seasons with the Athletics.)

The Red Sox were coming off a three-game series in Washington where Williams went 2-for-10, dropping his average from .406 to .401. And because of Mack’s schedule adjustment, Williams didn’t have just one off-day to think about how he close he was to dropping below .400, he now had two. So he got some hitting in, reporting to the ballpark on Friday for extra batting practice at the suggestion of manager Joe Cronin.

The other thing Williams had to think about was the pitchers he would face – three rookies who had all made their Major League debuts earlier that month.

“They were all kids he never had seen before, and he hated this,” Cronin said, according to Leigh Montville’s book “Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero.” “Ted would rather face the best than someone he had never seen before. Part of Ted’s great success as a hitter was the way he studied pitchers. Even then he got to know more about the pitcher than the pitcher knew about himself. With new kids he never had faced or seen before, he lost his edge. So he was worried about this.”

Williams was right to be worried. In the first game at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park on Sept. 27, 1941, right-handed knuckleballer Roger Wolff, 30 years old and playing in just his second Major League game, held him to one hit in four at-bats, dropping his average further – to .39955, rounded up to .400 in some observers’ eyes (and the official record books).

But not others’. Plenty of headlines the next day looked beyond the third decimal:

“Sox Top A’s; Williams Falls to .399”

“Ted’s Average to .39955; Last Try at .400 Today”

“Williams’ Batting Average Now .39955; Chips Down Today”

“Ted Williams Slumps Below .400 With Two Games Left”

“Williams’ Average Drops Below .400”

“Ted Williams Slips Below .400 Mark”

“Rookie Drops Ted Williams To .399 Mark”

“Ted Williams Batting .399”

He saw it the same way. Rather than ruminate in his hotel room that night, Williams and Red Sox equipment manager Johnny Orlando – who had bestowed “The Kid” nickname on Williams when he arrived at his first Spring Training – went out for a walk. For three hours. And 10 miles (at least according to Williams’ autobiography, “My Turn At Bat”).

“The night before the final game of the season I walked the streets of Philly with Ted,” said Orlando, who was just a few years older than Williams. “We walked for over three hours, and my feet were burning. Ted didn’t drink, so from time to time I’d run into a bar room to get a drink, and he’d wait outside until I got finished, drinking a soft drink. During the whole conversation all he kept repeating, over and over, was how determined he was to hit .400.”

When the pair returned to the team hotel, Cronin and a coach were sitting in the lobby. Williams joined them and they talked until midnight.

“It was during this discussion that I asked him, ‘How do you want to handle it?’” Cronin said. “He said, ‘I want to play it out. I want to play it all the way.’ As far as I was concerned, that was it.”

The next morning, Sept. 28, Williams and roommate Charlie Wagner, a 28-year-old pitcher, took a cab to the ballpark.

“The ride out was quiet,” Wagner said. “At the park, Ted took early batting practice. Ted wanted to play in the worst way.”

On the mound in the first game of the doubleheader was 20-year-old rookie Dick Fowler, making just his fourth appearance. Williams was batting cleanup, his customary spot in the lineup during the second half of that season (after generally batting third before the All-Star Game). Facing Fowler to lead off the second, Williams singled to right. His average was up to .40089.

Three innings later, Williams started the fifth with his 37th home run; he was now batting .402.

In the sixth, Mack went to his bullpen, calling on 22-year-old left-hander Porter Vaughn. The southpaw had pitched two innings against the Red Sox in 1940 but had spent most of ’41 in the Minors. This was his fourth appearance, and the first against Boston.

Williams singled, raising his average to .404.

The two faced off again in the seventh. Another single: an RBI and a batting average of .405.

Williams had one more at-bat coming, in the ninth. The Red Sox trailed, 11-10, and Mack brought in his third pitcher of the day, Tex Shirley, a 23-year-old right-hander making his fifth appearance. Williams led off, hitting a grounder to second that was booted by Crash Davis for an error. Williams was on first with a 4-for-5 day, but his average slid to .404. (Williams was erased on a double play, but the Red Sox rallied with two outs. Williams’ roommate, Wagner, drove in two runs with a bases-loaded single, then shut down the A’s for a 12-11 victory.)

Between games, the 41-year-old Grove was honored before taking the mound to start the nightcap. The future Hall of Famer didn’t have much, though, giving up three runs in the first in what would be the last inning of his career. The A’s started 22-year-old Fred Caligiuri, making – wanna guess? – the fifth start of his career. But Williams was locked in, leading off the second inning with a single to pull his average back up to .405.

In the fourth, with the Sox now down 4-0, Williams smoked a double that slammed into the right-field wall, leaving a hole in a speaker mounted there. He later said it was the hardest he had hit a ball to that point in his career. But more importantly, his average was now at .406593 – or .407. Williams got one more at-bat, leading off the seventh with the A’s now leading 6-0. He flied out to left to finish 2-for-3, his average settling at .406 – or .405701, rounded up.

That the Red Sox lost, 7-1, in a game called after eight innings because of darkness was secondary. Ted Williams had done it. Rather than sitting out one or both of the final two games of the season to protect his .400 average, the precocious slugger put it on the line and went 6-for-8 to secure his place in history.

“If I’m going to be a .400 hitter,” Williams said at the time, “I want more than my toenails on the line.”

With the season complete, Williams led the Majors in batting average, on-base percentage (.553), slugging (.735), OPS (1.287), runs (135), home runs (37) and walks (147). His 120 RBIs were five shy of Joe DiMaggio's MLB-leading total – and thus five short of the Triple Crown, something Williams would accomplish in 1942 and 1947. And yet, despite all those league-leading numbers Williams finished second to DiMaggio for the AL MVP, likely because the Yankees won the pennant by 17 games over the Red Sox and DiMaggio stole the summer with his 56-game hitting streak.

Williams’.553 on-base percentage in 1941 was also a Major League record that stood for 61 years until Barry Bonds topped it in 2002 (.582), then again in 2004 (.609).

"It was something that required a kind of nonstop consistency," Williams said of his .406 season in 1991. "I never thought of it as going 2-for-5 every day, but that's what it adds up to. I had to maintain my focus throughout. Although I never imagined that all these years later, no one else would do it again.

"If I had known hitting .400 was going to be such a big deal, I would have done it again."