You’d think that would be a monumentally successful year, the kind you talk about for decades. For most franchises, it would be. Yet for the 2022 Dodgers, it's almost par for the course. It's getting less play than a local television reporter injuring himself going down a slide.

The main baseball topic, when it’s not coming to terms with the fact Walker Buehler will not be returning, or wondering about Clayton Kershaw’s back, is angst over the struggles of Cody Bellinger and Craig Kimbrel. They are, again, on pace to win 113 games.

Such is the life, we suppose, of a franchise that has been dominant for a full decade now. What we need to do is explain how the 2022 team has been this good despite an endless run of pitching injuries and a handful of no-show appearances from important bats, and we will, but that almost seems somewhat small-picture here. There's a much more important question at play, which is: Have we ever seen a multi-season run quite like this?

A decade's worth of dominance

When the Dodgers win the NL West this year, and they will, it will be their ninth division title in the last 10 seasons. The one time they didn’t, the one massive failure in the last decade ... was last year, when they won a franchise-record-tying 106 games and avenged their second-place finish in a playoff defeat of the Giants anyway.

Since the start of this run in 2013, they’ve won 70 more games than the second-place Yankees, and 266 more than the last-place Marlins. (Yes, you can read that as saying if Miami had a full extra season in that time, and they went 162-0 in that season, they’d still have 100 fewer wins.)

In fact, let’s split the run into two parts, with the 2013-’16 teams (.565 winning percentage, four division titles, no World Series appearances, straddling the Ned Colletti/Andrew Friedman eras) being “the pretty good times,” and the 2017-’22 teams (.644 winning percentage, five division titles [including this year], three World Series appearances [so far]) as “the insanely good times.”

What we want to know, then, is how this run, the 2017-22 run of devastation, stacks up. We’re not talking about titles, necessarily, though of course that’s the ultimate goal. (In large part, it was simply a lot easier to win rings in the pre-playoff days; legends like Jackie Robinson, Babe Ruth, and Joe DiMaggio played exactly zero non-World Series playoff games. Robinson’s 1955 Dodgers finished up against the last-place Pirates on Sept. 25 and started the World Series against the Yankees on Sept. 28.)

No, we’re talking about this, the day-in, day-out dominance, over many seasons, over hundreds of games. We’re talking about the kind of success that basically becomes second nature, to the point that winning is less “exciting” and more “expected.” We’re talking about consistency, we guess. Consistent greatness, not a single flukish run to the Fall Classic.

What we’re talking about, then, is 533 wins in 827 games. Why that random-seeming number? Because that’s how many regular season games (entering this weekend’s Marlins series) the Dodgers have played since 2017, which is when they really turned it up. It’s almost better than “seasons,” because season lengths haven’t been consistent. They have a .645 winning percentage in that time. Has any club ever done that? Well, yes. But it’s been a very, very long time.

Setting aside overlapping spans of the same team era, the best 826-game runs have been ..

- .693 1905-’11 Cubs

- .664 1927-’33 A’s

- .663 1940-’46 Cardinals

- .656 1937-’42 Yankees

- .653 1952-’58 Yankees

- .651 1901-’06 Pirates

- .647 1909-’14 A’s

- .647 1908-’13 Giants

- .645 2017-’22 Dodgers

That’s it -- and look hard at the dates attached to those clubs. Of the eight, seven played a non-integrated, prehistoric version of baseball, barely comparable to today’s game. The only post-war group there are the 1950s Yankees of Mantle, Berra and Ford, who are considered one of the legendary groups of all time -- but even they never went west of St. Louis or played in more than an eight-team league.

What the Dodgers have done, then, hasn’t been done in more than six decades, when the sport and the world were very different places.

Maybe it’s easier to think about it this way. Remember, above, when we said they have both scored the most runs in the Majors, and have allowed the fewest? Should they keep that up, it will be the fifth time in a row they’ve pulled off that dual trick, which …

... would be a new record. It's never happened. This kind of dominance isn’t ordinary. It’s not normal. It doesn’t happen, especially in today’s game. Except, of course, when it does.

What's going right in 2022

But back to 2022, which might end up being the best full-season team in franchise history, despite the fact that it so often hasn’t felt that way, perhaps in part because Kimbrel has struggled, or because the injuries keep plling up -- Blake Treinen hasn’t been seen since April -- or because the pitching stars have so often been Rockies castoff Tyler Anderson or Orioles castoff Evan Phillips or Marlins castoff Alex Vesia or Rockies castoff Yency Almonte or Angels/Yankees castoff Andrew Heaney or Brewers castoff Phil Bickford or ... well, you get the idea. It’s what they’ve been doing for years; find pitchers, make them better.

If that undersells long-time starter Julio Urías and homegrown Tony Gonsolin, it also helps point out that they’ve allowed the fewest runs without full seasons from Kershaw, Buehler, Treinen, Heaney or Dustin May, who should return from injury on the upcoming homestand.

Their pitching has the fifth-highest strikeout rate and the second-lowest walk rate, which seems like a tremendous place to start. When they do allow contact, it’s the lowest hard-hit rate of any team. Even that contact often isn’t great, because they have the second-highest pop-up rate and the third-lowest line drive rate.

They throw the third-most valuable fastballs ... but also the third-most valuable breaking pitches and the second-most valuable offspeed pitches. Almost no one throws more strikes, but at the same time, almost no one gets more chase, either. When the balls are put in play? No defense turns more of those balls into outs.

What comes out in the wash there is that their 2.73 ERA is so far above the 3.99 average for the season, that if you go back to the end of the war in 1945, they’re on track to have the biggest gap between team ERA and league ERA any National League team has had -- and second largest of any Major League team overall in that time, behind only Cleveland’s 2017 club. They do not allow runs.

All of which would be hard enough, if not for the fact that they outscore everyone, too, and here it’s tempting, easy, and not entirely incorrect to point to the highly-paid trio atop the order – Mookie Betts, Trea Turner, and Freddie Freeman. Sometimes it’s as simple as “have great stars,” and they do; the top three out produces every other top three in the game except for that of the Yankees.

But then something odd happens, which is that the lineup can get a little soft in the middle. While catcher Will Smith has been fantastic, Bellinger, Justin Turner, and Max Muncy have all had their struggles, and so the 4/5/6 spots of the order have a mere .707 OPS, which is just 19th-best this year.

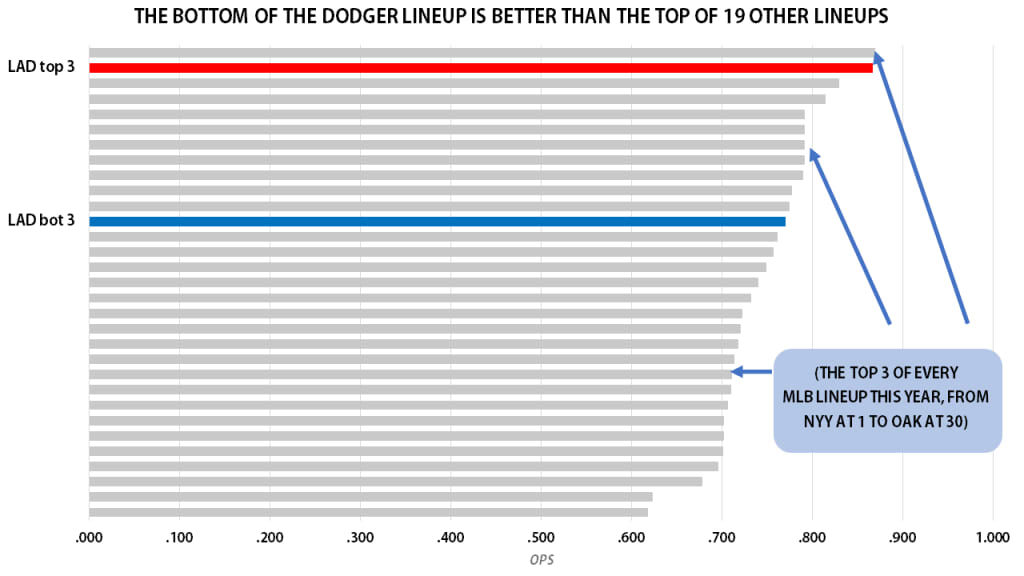

No matter, though. The bottom third of the order -- primarily names like Gavin Lux, Chris Taylor, Trayce Thompson, at times Bellinger, now Joey Gallo, and others -- has been so good (.771 OPS, best of any bottom trio) that it actually allows us to present this otherwise nonsensical chart.

Los Angeles’s bottom three is performing better than the top three of more than half the rest of baseball.

It becomes, then, almost rote to recite the batting version of the pitching stats above, and yet it must be done. No team hits fewer ground balls, because ground balls do not win games; in fact, no team has had a lower ground ball rate than the 2022 Dodgers since pitch tracking came online in 2008. They chase outside the zone less than anyone, because those are not crushable pitches, which is sort of their thing; four of the six lowest chase-rate seasons on record are recent Dodger teams, but not even this Dodger team.

They hit the ball hard, obviously; fourth-best in hard-hit rate and third-best in barrel rate. They’re the fourth-best team with runners in scoring position, but they’re the best team without any runners on at all.

It is, for lack of a better term, relentless. (It’s worth noting here, the pipeline is far from dry; they still have the NL’s best farm system, with flame-throwing Bobby Miller potentially in play to assist later this season.)

What it might not be is exhilarating, in the same way that you might get sick of eating your all-time favorite meal night after night, year after year. Ultimately, all that’s going to matter from this run is how many rings they win, in the same way that the 1990s Braves are remembered more for winning just one title than they are for winning 14 consecutive divisions.

These Dodgers will never win five straight titles like those early 1950s Yankees did; it’s just not possible in today’s playoff structure. They might need to win at least one more to fully get into the "dynasty" conversation, as ill-defined as that can be. But make no mistake, they're already there. They're winning consistently, and regularly, and more often than any team in most of our lifetimes.