Dave Smith has spent the vast majority of his 75 years poring over baseball’s smallest details. On a Sunday afternoon in February, his attention was fixed on finding out exactly what happened on every play in a 1919 ballgame between the Tigers and Yankees.

Over the next few hours in his home office, Smith used six newspaper stories from the game to piece together the action. But more information isn’t necessarily better.

“They don’t always agree,” he admitted.

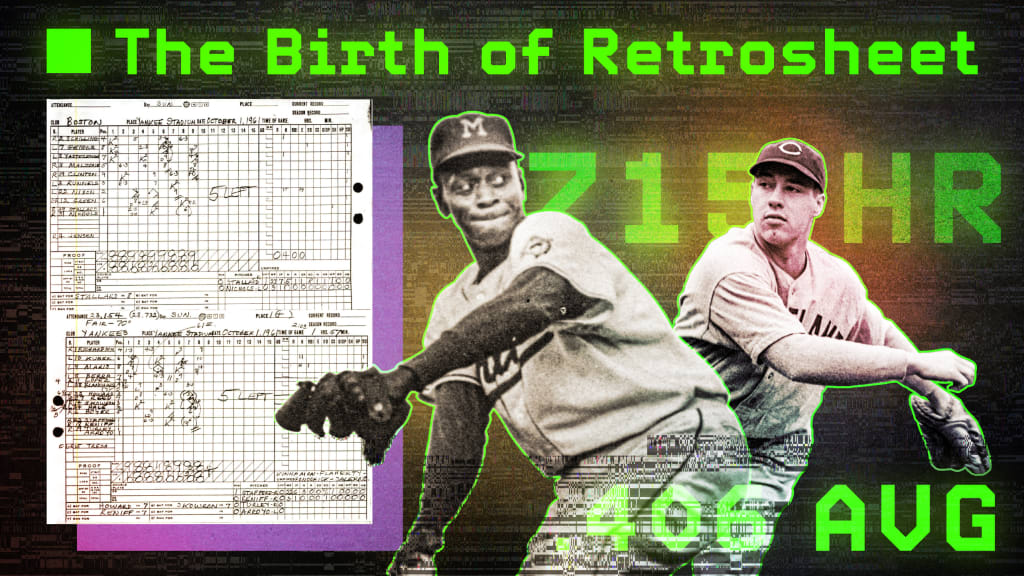

Information and evidence are what Smith craves. A longtime University of Delaware biology professor, Smith categorizes these baseball deep dives as his hobby. But that hobby has a name and a legacy: Retrosheet.

An indispensable source for researchers, writers and fans alike, Retrosheet laid the foundation for today’s most popular baseball statistics sites.

"Before Baseball-Reference, there was no other place to get this except us. There really wasn’t,” Smith said.

For 34 years, Smith along with hundreds of volunteers have collaborated to achieve Retrosheet’s extremely ambitious quest: Providing play-by-play accounts for as many Major League games as possible, archive them and make them available to share with anyone for free.

To date, the organization has produced 184,000 play-by-play accounts for games since 1920 -- all American League and National League games played throughout the past 102 years. If you include just box scores, Retrosheet contains information on 205,000 games since 1901. They are compiling the same data for Negro Leagues games as well.

And there are no plans to stop until every Major League game is accounted for.

It’s a task so immense that MLB’s official historian, John Thorn, stated that it “might have daunted Imhotep, the pharaoh's architect, as he contemplated the pyramid before setting a first stone.”

‘This is the most wonderful thing in the world’

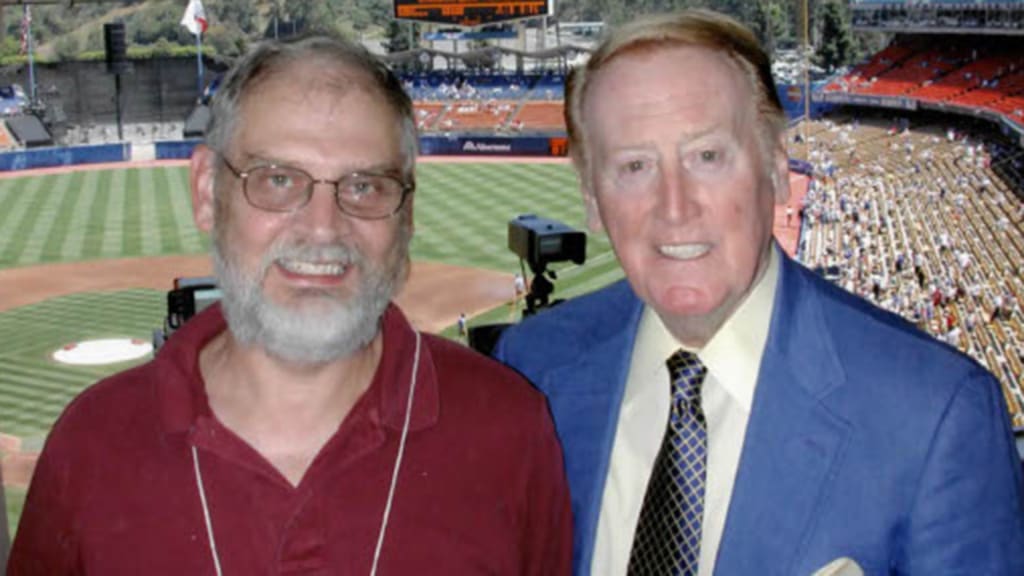

Retrosheet formally began in 1989, but the seeds for the idea were planted on July 18, 1958, when a 10-year-old Smith went to his first MLB game with his father: Phillies vs. Dodgers at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum -- with Smith’s boyhood hero, Sandy Koufax, on the mound for L.A. However, the game didn’t impact Smith’s future as much as what he received at the stadium; his father bought him a Dodgers almanac compiled by Allan Roth, the first full-time statistician in baseball history.

Month-by-month statistical breakdowns on each player. Home and away splits. Platoon splits. They were all here, and Smith was hooked.

“I was absolutely convinced that this is the most wonderful thing in the world,” he said.

Fast-forward to 1983, when sabermetric pioneer Bill James began “Project Scoresheet,” a collective effort by volunteers to record every play of every game, starting with the 1984 season and moving forward in time.

Smith doesn’t consider Retrosheet a sequel or subsidiary to James’ invention, but it did evolve out of it with two key differences:

- Smith was more interested in sharing baseball’s past than its present.

- As Project Scoresheet collapsed over discord due to money, Smith decided his creation would be non-profit.

“The very first decision was that no dime would ever change hands, period,” he said. “It has to be free. And everyone who volunteers for us … they always know from our first conversation, everything you do can and will be given away for free to anyone who wants it. If you don’t like that, that’s great. If you don’t want your labor to be used that way, I’ve got no problem with it. But I’ve told you up front -- and if you don’t like it, now is the time to get out.”

Smith adds that no volunteer has ever asked him for any money for their contributions.

Members of Project Scoresheet were among those who joined Smith in ‘89 to begin capturing baseball’s past, one game and one play at a time.

Early on, Smith discovered that many newspapers of the early 20th century, before the advent of radio and television, published full play-by-play or extremely detailed game stories each day. They were all accessible through the University of Delaware via interlibrary loan.

“We’ve got tens of thousands of games that I got that way,” he said. “... I spent I-don’t-want-to-know-how-many hours sitting at microfilm machines reading on this.”

The Orioles were the first MLB team to allow Retrosheet access to their scorebooks, providing sheets dating back to 1954. Although most clubs ignored Smith’s initial requests to photocopy what they had, eventually every team handed over batches of records. Smith quickly found himself stuffing filing cabinet after filing cabinet with baseball history.

For the first few years of Retrosheet, whatever was found through a variety of sources was compiled and summarized for a newsletter. Whoever wanted their data could get it on a floppy disk.

As word spread of their efforts, people began reaching out to Smith, either asking if he could find a play-by-play account of a certain game or submitting one of their own. Perhaps it was from their first game. Perhaps it was from their last with a cherished family member.

“People are inviting me into their lives 50 years later and they don’t even know it,” he said. “That’s really powerful.”

The legendary San Francisco sports writer Bob Stevens once gave Smith 30 years worth of Giants scorebooks and told him, “I don’t know why I saved these things. I haven’t looked at them in years. I guess I was saving them for you.”

A century of numbers

Inarguably, the most important set of documents in Retrosheet’s possession came from the Baseball Hall of Fame. Specifically, giant year-by-year ledgers that contain a daily record of what each player accomplished in each game of a season.

These ledgers, which Smith guesses each weigh between 20 and 30 pounds and are 25 inches by 30 inches big, feature player stats submitted every day by a game’s official scorer. Those statistics were then compiled and transcribed by the league office. The end result was handwritten player game logs for the large majority of the 20th century. A new line of stats was added to a player’s page for each game played, and each enormous page featured about 40 lines worth of numbers. So, a hitter who participated in 150 games might take up three or four pages in that season’s ledger.

The early years of these accounts from official scorers had plenty of missing data, such as strikeouts for hitters or the number of hit-by-pitches charged to pitchers, but they are the “gold standard,” according to Smith, and serve as the backbone of Retrosheet’s earliest box-score files.

“Without [the ledgers], we’d be dead,” Smith said.

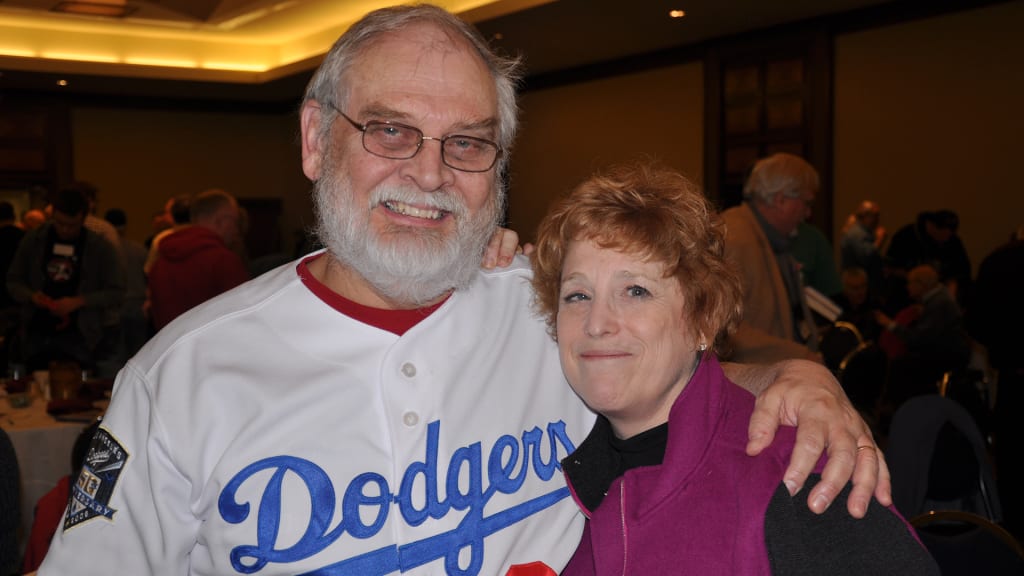

The Hall of Fame microfilmed multiple copies of the entire set of ledgers -- dating from 1903 in the NL and 1905 in the AL and covering every year into the 1990s – and let Retrosheet purchase one. Smith admitted this gigantic cache wasn’t cheap, but he felt lucky that his wife, Amy, told him, “Your hobby is supposed to cost you money.”

Now, considering how that treasure trove of information was put together, you are probably wondering one thing:

How are Smith and company so sure that what they input into Retrosheet is the absolute truth?

Perhaps the official scorer made a mistake a century ago. Maybe the press coverage contains contradictions.

The quick answer: They do the best they can with what they have.

“Dave, in particular, doesn’t want to say we’re right,” said Tom Thress, who became Retrosheet’s president in June after Smith decided to take a step back from the organization. “We create a plausible account and it’s kind of left as an exercise for the reader.”

With the help of those scorebooks, newspaper articles, radio and TV accounts, et cetera, Retrosheet deduces the most likely occurrence of each play. These “deduced games” -- like that 1919 Tigers-Yankees game that Smith was working on -- comprise a large chunk of Retrosheet’s play-by-play output. Whenever Retrosheet’s determination differs from the official scorer’s files, that’s noted in the site’s discrepancy files.

Smith says that just in the 1920s alone, the American League and the National League each have more than 2,000 discrepancies each year.

“I’ve been challenged by people -- sometimes it’s a little annoying -- ‘How do you know that you’re right?’ Well, I don’t know that we’re right. I’m not presenting truth. I’m presenting what we have the best evidence for. And if you give me better evidence, I’ll change what we have.

“But in the meantime, the best evidence is what the official scorer wrote down and got transcribed onto these logs. Sometimes, they made mistakes and so we keep track of places where we differ from them.”

Retrosheet takes off

Retrosheet’s maiden venture to compile a full play-by-play record of the 1983 season took three years to complete. But by that point, the internet age was peeking over the horizon, and Retrosheet’s website launch in 1994 enabled it to find, upload and disseminate information to its rapidly expanding fan base at exponentially faster rates. According to Thorn, Retrosheet represented “the new frontier in statistical baseball research, in tandem with sabermetric analysis.”

By the mid-2000s, Retrosheet’s reach and impact within the baseball community were easy to spot. Smith recalls a story told by David Vincent, Retrosheet’s founding secretary and the Washington Nationals’ official scorer from 2005-15. As he strolled through the press box during a Nats game at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium, Vincent glanced over the shoulders of six or seven sportswriters. All of their computer screens displayed the same site: Retrosheet.

“That was when I knew we had really hit it,” Smith said.

Today, those screens might be more likely to display Baseball-Reference or FanGraphs, both of which acknowledge their use of Retrosheet’s play-by-play data on their homepages. That’s just fine with Smith; making Retrosheet’s discoveries accessible to anyone free of charge is one of the organization’s chief tenets.

“America’s national game, the primary record of what happened,” he said, “it just seemed so appropriate that it should be made available to everybody.

“The fact that other people find it interesting kind of blows my mind. That it’s usable by other sites is just superb. I couldn’t be happier about that.”

No matter the level of outside interest, Retrosheet’s ultimate mission of presenting play-by-play data for every Major League game continues apace. A development a few years ago, however, made the mission simultaneously more comprehensive and likely impossible.

The Negro Leagues are Major Leagues

Taking inspiration from Bill James’ Win Shares metric, Thress used Retrosheet’s play-by-play information to create his own metric -- Player Won-Lost Record -- years before he first volunteered for the site in 2014. He remembers his first assignment called for him to deduce what happened in a 1949 Phillies game, and he has been enraptured by the process ever since.

“I’m always dazzled by how much was recorded at the time and how much of what was recorded has survived to the present,” Thress said.

In 2020, Thress, an economist based in Chicago, had an idea: He wanted to incorporate Negro Leagues players and stats into his won-lost metric and suggested that Retrosheet should delve into that history the same way it has tackled the American and National Leagues.

“My first thought was this is the most wonderful thing I’ve heard in a long time,” Smith recalled.

Near the end of that year, MLB bestowed Major League status upon seven professional Negro Leagues that operated between 1920 and 1948.

If Retrosheet’s goal is like putting together a massive puzzle, more pieces had just been added.

“I guess we’re all in,” Thress thought when the announcement came down. “We’ve got to do this.”

Thress and Smith knew that this endeavor would be much more difficult than Retrosheet’s work on AL and NL games. There were no giant ledgers to guide them. Many records from the time have been lost, and those that survived give sparse details.

There were games that received a lot of coverage: Black publications published full play-by-play of the Negro League World Series during the 1920s as well as of East-West All-Star Games in the 1930s and ‘40s. For season-level data such as team rosters and approximate schedules, Retrosheet’s starting point is the Seamheads Negro Leagues database, which is also used by Baseball-Reference. Those resources were where Thress and other volunteers began Retrosheet’s reconstruction of the Negro Leagues.

Beyond that, things get very murky. The site has released files for Negro Leagues seasons from 1942-48, but the details within are thin. A box score may contain only a handful of hitters and one starting pitcher, much less a full play-by-play account. Thress says that he dreams that he will have his own Bob Stevens moment, when someone contacts him after finding a pile of Negro League scoresheets in their grandfather’s attic. Any information that sheds more light on the rich history of this side of baseball is welcome.

“Because it’s so hard and it’s so rare to actually find really good stuff, oh my God, you’d find a box score and you’ve hit the lottery,” Thress said. “It’s just an amazing feeling.”

Negro League exhibitions and barnstorming games are also within the site’s purview. That includes a 16-game barnstorming tour that pitted the Bob Feller All-Stars against the Satchel Paige All-Stars in 1946. In this case, more information is better.

“Dave likes to say that the thing about Retrosheet is it’s huge but it’s finite,” Thress said. “There’s a finite number of games. In terms of AL/NL, there are. And Retrosheet will finish it. God willing, they will finish in my lifetime.

“The Negro Leagues throw a little twist in there because, in theory, there were a finite number of Negro League games, but we don’t necessarily know what that number was. Throwing the Negro Leagues in there has, to some extent, made the completion of the project impossible whereas -- in theory, it wasn’t before. But we’ll see.”

The work continues

Smith guesses that between 400 and 500 volunteers have contributed to Retrosheet over the years, with about a dozen people working on this baseball labor of love at any one time. They will likely complete deducing games from the 1919 AL/NL season within a few weeks and then move on to 1918. Thress is among those wrapping up the 1940 Negro Leagues season and beginning the site's dive into 1939. He is also looking into the 1900 National League season. Others have started deducing games from the 19th century, predating those enormous ledgers.

Smith understands there are box scores and plays that Retrosheet will probably never be able to display. But that doesn’t lessen his drive to help finish what he started.

“Finding the games to complete the set, that is my biggest push,” he said. “Always has been.”