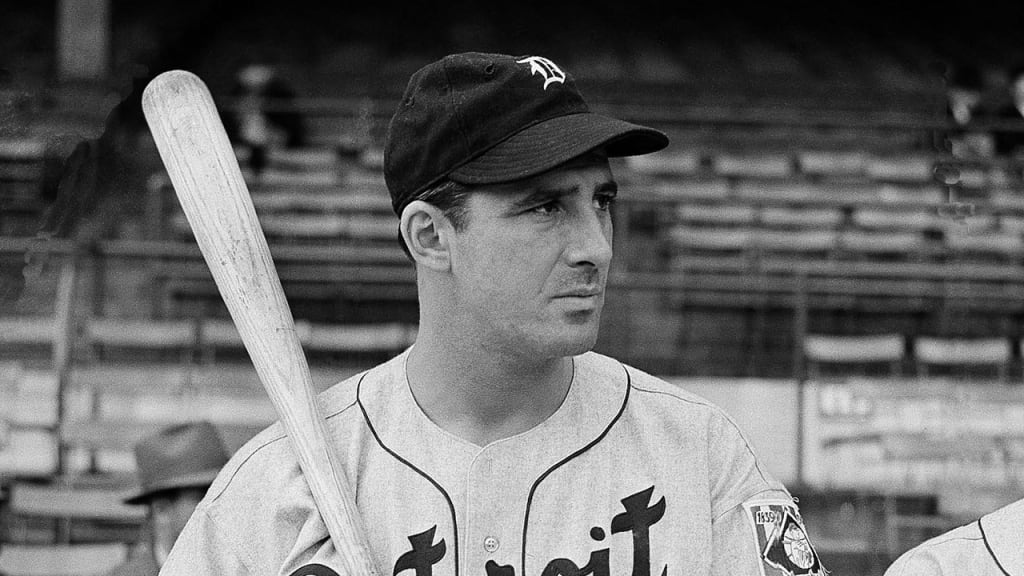

In the summer of 1938, Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg took a run at Babe Ruth's already-mythic record of 60 home runs in a single season. Will-he-or-won't-he speculation dominated the second half of the schedule.

At the same time, war clouds were gathering in Europe as Adolf Hitler's war machine began setting the stage for the conflict that would eventually become World War II.

Greenberg was one of baseball's first Jewish stars. Those three realities serve as the foundation for Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Home Runs in the Shadow of War.

The Nazi atrocities against Jews and other minorities are well-documented. And author Ron Kaplan strongly makes the point that racism, anti-Semitism and strong opposition to immigration was also rampant in the United States at the time.

There's no doubt that Greenberg's religion impacted him over the course of his career. He was the target of slurs from opposing players because of his beliefs just as Jackie Robinson would be a decade later because of the color of his skin. In fact, Kaplan recounts a touching story about how Greenberg, closing out his career with the Pirates when Robinson was a rookie, went out of his way to openly support the Brooklyn Dodgers trailblazer.

What's less clear is how profoundly Greenberg was specifically affected during the season in question -- when he ended up with 58 home runs -- by the troubling developments in Europe. In the quote that opens the book, he says: "It was 1938 and I was now making good as a ballplayer. Nobody expected war, least of all the ballplayers. I didn't pay much attention to Hitler at first or read the front pages, and I just went ahead and played. Of course, as time went by, I came to feel that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler."

Which isn't to say that being Jewish was a non-issue during that historic season. Example: In those less politically correct times, Greenberg and teammate Harry Eisenstat were openly referred to as Detroit's "Hebrew combination" in a Washington Post story.

The most intriguing anecdote revolves around the suggestion that opposing teams conspired to keep him from breaking Ruth's record simply because of his beliefs.

Those suspicions apparently picked up steam in September when Greenberg started the month by being walked 11 times in eight games.

Kaplan reaches no firm conclusion, instead presenting both sides of the story. Yes, Greenberg ended up walking 119 times that season. But Ruth walked 137 times in 1927 when he set the record. And aren't pitchers always going to be tempted to work around the best hitter in any lineup?

There's a fascinating story about Greenberg's penultimate homer, an inside-the-park round-tripper. Greenberg later admitted that he was "out by a mile" at the plate and also called the allegations of a widespread effort to deny him "pure baloney."

On the other hand, Kaplan cites a statistical analysis that appeared in The New York Times that purports to show that Greenberg received more than the normal amount of walks down the stretch.

The backbone of this book is a game-by-game look at the Greenberg's quest during a disappointing Tigers season. The strength is that it is plainly juxtaposed against not only the political situation in Europe but the domestic issues, including fear and bigotry, being faced by a country still recovering from the Great Depression. Telling details, such as how the Joe Louis-Max Schmeling heavyweight championship bout became a proxy for nationalistic fervor.

Greenberg was inducted into the Hall of Fame on the basis of his performance on the field. But, as this volume makes clear, he also encountered hurdles along the way that most players didn't have to contend with.