Hey … Dad? You wanna have a catch?”

—Kevin Costner as Ray Kinsella, speaking to his father, John, in Field of Dreams

What father among us hasn’t found a lump in his throat, a knot in his belly, eyes misty because of the, ahem, dust in here, when watching Field of Dreams?

For a quartet of former Yankees, every Father’s Day in June — heck, every day — is like that.

They are part of a unique club — fathers who once donned the pinstripes who now have sons also playing in the majors.

Yankees Magazine caught up with the four ex-Yanks to talk about the father-son dynamic, the wit and wisdom they imparted on their respective boys, the immeasurable pride they have, and the common bond that fathers often share with their kids — baseball.

***

“It’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great.”

—Tom Hanks as Jimmy Dugan, explaining the complexities of baseball in A League of Their Own

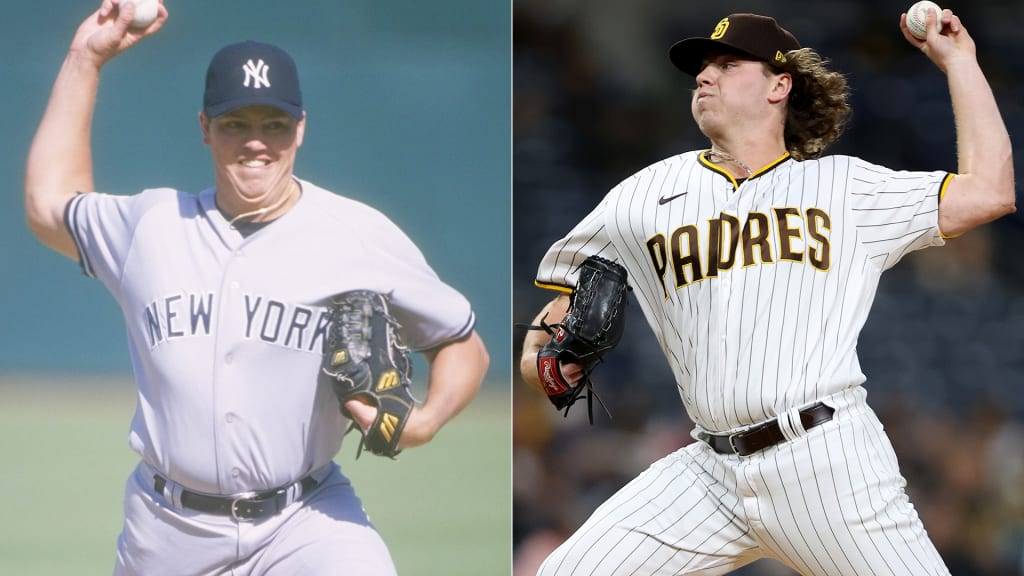

That’s all that former Yankees pitcher David Weathers wanted his son Ryan, a pitcher with the San Diego Padres, to understand about pursuing the same profession that he once had.

Baseball’s path is never easy, whether you’re the son of a major league player or not. David, who appeared in 21 regular-

season games for the Yankees from 1996 to ’97, said the only advice he gives Ryan now is more mental, more cerebral, and less mechanical.

And David said he got that from Joe Torre.

“I’ll never forget this,” Weathers says. “It was 1997, spring training. Joe and I were talking, and he said to me, ‘You know David, with your stuff, you could get Mantle, Maris and DiMaggio out all in a row, but you can’t get the bottom of the order out. That’s what you have to figure out.’ And he was right. I could get the 3-4-5-6 hitters out, but I struggled with 7-8-9. Joe Torre was a guy that truly helped me, and that’s what I tell Ryan. You have to think. You have to figure it out.”

So far, it seems like the younger Weathers has done just that. Through mid-May of this season, the left-handed flamethrower — David was right-handed and readily admits he was not the power pitcher his son is — had been dominant. Ryan had appeared in eight games and posted a microscopic 0.81 ERA, going 2-1 with one save. On April 16, the 21-year-old — the youngest pitcher in Major League Baseball at that moment — wowed observers with 3 2/3 innings of one-hit ball against the defending champion Los Angeles Dodgers.

In fact, Weathers’ paltry 3.6 hits per nine innings even prompted Padres manager Jayce Tingler to start imagining other ways to deploy him.

“He’s going to start some,” Tingler told the San Diego Union-Tribune in May. “I don’t know what’s going to happen. I know he’s capable of coming out of the ’pen. He’s capable of starting. We’re going to need the depth.”

Weathers’ natural ability should not come as much surprise; he has been in major league clubhouses since he was 6. He fondly remembers wrestling with Ken Griffey Jr. — another second-generation player — when David pitched for the Cincinnati Reds from 2005 through ’08, and became a Gatorade National Player of the Year after leading Loretto High School to a Tennessee state championship.

“I got to see my dad do it, and I wanted to do it, too,” Ryan told The Athletic. “I don’t think I ever really thought of anything else other than baseball.”

Ironically, David said that as good as Ryan was, and as strong as his work ethic was, it took him a while to have that ‘A-ha!’ moment that his son could play in The Show.

“Ryan was a late bloomer, and his body just started growing and he started getting stronger,” says David, who earned his 1996 World Series ring by allowing just one run over seven postseason appearances. “When he was 15, it was like, ‘Wow.’ I will never forget going inside and telling his mother, ‘Um, he’s throwing seven or eight miles an hour faster than last year,’ The ball was just coming out of his hand so clean. He never threw a curveball until he was 16. We made sure he had fastball command and a changeup, and now that’s what everybody loves about him.”

Well, that and his mental makeup, courtesy of his father.

“The only things I really impressed upon him was that there are going to be days when you get your feelings hurt,” David says. “You’re going to get hit, and hit hard. So, you have to harness your mental side. Because the fact remains, you can’t prepare anybody for the big leagues.”

***

Pop: “You know, my mama wanted me to be a farmer.”

Roy: “My dad wanted me to be a baseball player.”

Pop: “Well, you’re better than anyone I ever had. And you’re the best [darn] hitter I ever saw. Suit up.”

—Wilford Brimley’s Pop Fisher and Robert Redford’s Roy Hobbs in The Natural

Baseball was never a given for Cal Quantrill, and his father, Paul, says that he never pushed it. After all, they were from Canada, where skates and a stick of a different sort were more popular than spikes and a bat.

“He played as much hockey as baseball,” says Paul, who pitched 108 games for the Yankees from 2004 through June 2005. The right-handed reliever went 8-3 during that span of his 14-year career. “My wife and I let the kids do what they wanted to do. Cal always loved baseball, but baseball wasn’t an expectation in our family.”

It is now. After making the majors in 2019 with the San Diego Padres, Cal was traded to the Cleveland Indians in August 2020. Following the trade, he appeared in eight games with the Indians during the truncated 2020 season and put up a sparkling 1.84 ERA. Through his first 11 games this year, Quantrill had a 2.12 ERA.

Indians pitching coach Carl Willis told Cleveland.com that what he likes best about the 26-year-old right-hander is he always knows what he’s going to get — an attribute that comes from having a father who played in the bigs.

“Anything we can bring to the table that’s going to help him get outs, that’s all he’s concerned with,” Willis said. “He’s a really engaging, smart young man who is a good mix of old-school and new-school, and I like that.”

While it might have been a battle between baseball and hockey when he was younger, it’s all baseball now for Cal. And Paul is about to gain a daughter-in-law who extends the family’s baseball ties — Cal is engaged to Eastin Ashby, daughter of former major leaguer and two-time All-Star Andy Ashby.

![After Paul Quantrill pitched for the Yankees from 2004-05, the team drafted his son out of high school in 2013. Cal Quantrill [right] chose to pitch at Stanford, and now he’s making a name for himself in Cleveland’s bullpen. (Getty Images)](https://img.mlbstatic.com/mlb-images/image/private/t_16x9/t_w1024/mlb/dzjrxxsbi9qystnr2gla.jpg)

Ironically, Cal Quantrill was originally selected out of high school by the Yankees in the 26th round of the 2013 draft, but it was fairly well known around the league that he wanted to attend college instead of making the immediate jump to the pros. Indeed, he opted to attend Stanford University.

“That’s the first time I felt he was all-in on baseball,” Paul says.

There was even a moment during his recruiting visit to Stanford when Paul finally felt certain that Cal was going to be a big-league player.

It was his quiet confidence, Paul says.

“The coach asked him what he would bring to Stanford,” Paul says. “Cal said, ‘I’ll be your Friday night starter as a freshman.’ I thought, Wow, that’s quite a statement to make.”

Cal enrolled at Stanford and in February of 2014, on the eve of the season opener, he called home to speak to Paul.

“I’m starting Friday night,” Cal told his father.

“Lots of pride,” Paul says. “Cal became the first Stanford freshman pitcher to start a game since Mike Mussina in 1988. I think I am far more proud of what he did in graduating in three years with an engineering degree than anything else.”

Paul says now, with Cal firmly entrenched in the big leagues, he serves more as a sounding board.

“We have lots of chats after games, but I am an anchor,” Quantrill says. “What can be dangerous as an ex-player is becoming part of his process. I don’t need to be a part of that. If he asks me a question, I answer the best I can.”

Paul then pauses and laughs.

“You know, Cal calls his mom when he feels like he needs some love,” Paul says. “He calls me when he feels like he needs to be critiqued.”

***

“You could be a kid for as long as you want when you play baseball.”

—Cal Ripken Jr.

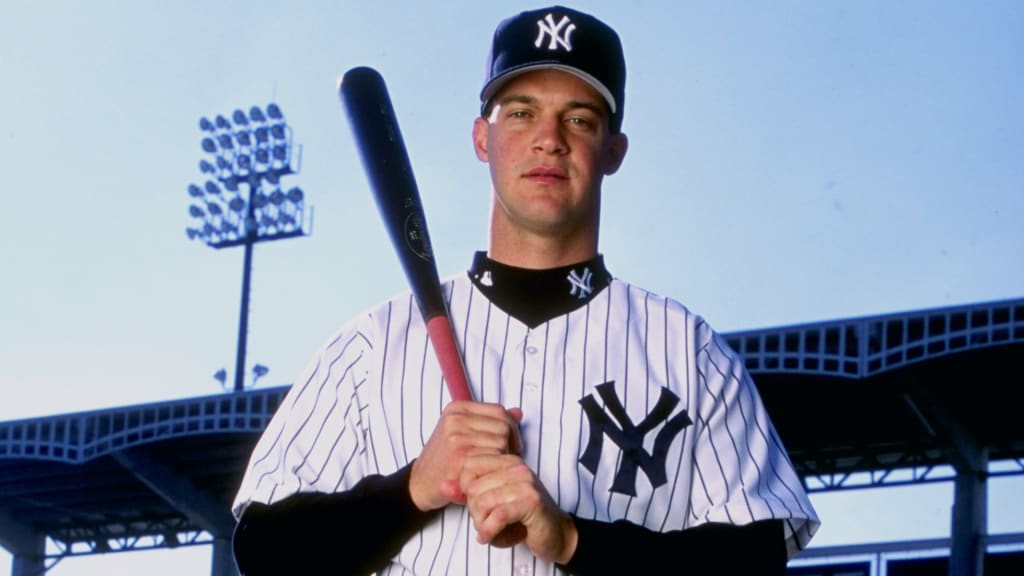

Charlie Hayes’ cell phone blew up almost every day in September of last year from family and friends. He was greeted at his baseball academy in Houston by well-wishers.

The former Yankees third baseman, who squeezed the final out of the 1996 World Series in his glove to give the team its first championship in 18 years, was even stopped by strangers who knew the face.

It wasn’t about him, though.

It was about his son, Ke’Bryan Hayes.

Ke’Bryan, also a third baseman, was called up to the Pittsburgh Pirates last season and exploded onto the scene. In 24 games, the then-23-year-old had 32 hits, batting .376 with five home runs and 11 RBI. Hayes finished sixth in National League Rookie of the Year voting despite not making his debut until Sept. 1.

Charlie wasn’t living vicariously through his son’s success, but he loved seeing it happen.

“I always believed in this kid,” says Charlie, who was plucked from the Yankees by the Rockies in the 1992 expansion draft but returned to New York via trade from Pittsburgh just in time for the team’s championship run in ’96. “I’ll be the first one to say every decision that he’s made has been the right one. I’m so excited for him. Whatever he achieves, he has understood the process. I don’t think we ever had a dinner at our table where sports wasn’t discussed, and those discussions turned out to be priceless.”

![His dad, Charlie [left] caught the out that secured the 1996 Yankees’ World Series title. But Ke’Bryan Hayes [right] is determined to stand on his own. A September call-up last year, Hayes earned Rookie of the Year votes by batting .376 with a 1.124 OPS for the Pirates. (Getty Images)](https://img.mlbstatic.com/mlb-images/image/private/t_16x9/t_w1024/mlb/gohnqw1jbkzyhp0zta3m.jpg)

Ke’Bryan was drafted as the 32nd overall pick in 2015 and was thrilled to play for one of the teams that his father had.

“Just to be able to wear the same major league uniform that my dad wore is really special and, hopefully, I can get up there to the major leagues,” he told My FOX Houston at the time.

Charlie is certainly a big reason for Ke’Bryan’s early success, but the elder Hayes refuses to take full credit. He has three boys, including Tyree, who was drafted by Tampa Bay in the eighth round in 2006. Tyree never got past the minor leagues, but what he learned from his father and his own experiences were invaluable in helping prepare Ke’Bryan for what was ahead.

“Being a professional athlete, and then being the parent of a professional athlete, that can be a tricky thing,” Charlie says. “I never wanted to lose my father-son relationship with any of my kids, so I pushed, but I wasn’t overbearing. In fact, I get a lot of credit when it comes to Ke’Bryan, but I think it’s really his brother. I passed on what I knew to Tyree, and Tyree passed it on to his brother. And as I think about it now, those kids during the summer would be outside seven, eight, nine hours a day working on their game.”

When Charlie was home in Texas during the offseasons, Ke’Bryan would be waiting. The youngster took 400 swings a day in the batting cage, Charlie says, and was diligent about it.

“His success didn’t surprise me last year because the better the competition was, the better he gets,” Charlie says. “He puts in the work. He made a commitment to the game. What he doesn’t know, he figures out.”

In his first at-bat of this season, Ke’Bryan homered at Wrigley Field off Cubs pitcher Kyle Hendricks on Opening Day. But a wrist injury sent Hayes to the injured list after just two games.

Charlie, who spent three of his 14 seasons in the bigs with the Yankees, knows the feeling.

“Injuries. Part of the game,” he says. “But that’s just another thing he’ll figure out.”

***

“Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel, not just to be as good as someone else but to be better than someone else. This is the nature of man and the name of the game.”

—Ted Williams

Now, you would think that somebody who has hit more than 120 home runs since bursting onto the scene in 2017 has just about mastered this great game we know as baseball. But Los Angeles Dodgers star Cody Bellinger is constantly working on his craft, no matter what his accomplishments are so far, and no matter how old he is.

“I love that about him,” says his father, Clay Bellinger. “He had a batting cage put in at his house, and I was just over there last week. He asked me to throw to him while he recuperates (from a hairline fracture in his left fibula). And I never felt like, ‘Man, I’m throwing to an MVP.’ I just felt like a dad throwing to his son.”

Clay Bellinger played for the Yankees for three seasons, from 1999 to 2001, winning two World Series rings. The Bellinger clan earned another one last season when Cody and the Dodgers beat the Tampa Bay Rays in the Fall Classic.

Cody was also the 2019 National League MVP after slugging 47 home runs, knocking in 115 runs and batting .305, on top of winning Rookie of the Year in 2017.

Good bloodlines, no?

But Clay says he and his wife never had to push Cody toward baseball.

“He picked up a bat one day, and that was that,” Clay says. “He and Cole, his younger brother, would just play catch and hit with each other all day.”

Cole Bellinger is a former minor leaguer who played in the San Diego Padres system and is good friends with Ryan Weathers. In fact, it was a camaraderie with other players’ children that also helped draw Cody into baseball.

“It was never who was in the clubhouse, it was who was in the family room at Yankee Stadium,” Clay says. “Cody would love to come to games, but what he really loved was hanging out and playing with Scott Brosius’s kids, or Paul O’Neill’s kids, or Andy Pettitte’s kids or Tino Martinez’s kids.”

Clay said he knew exactly when Cody had the stuff to be a major leaguer.

“Little League,” Clay says without hesitation. “He was so small but so good. His swing was such a good swing at an early age it was just a matter of time of getting some weight on and growing.”

Fathers and sons and baseball.

It’s one of the most unique arrangements in all of sports. In fact, according to Baseball Almanac, there have been only 248 pairs of fathers and sons who have both played in the majors. It dates back to when Jack Doscher made his big-league debut in 1903, becoming the first son of a former major league father to play at the top level. His dad was Herm Doscher, who made his debut in 1876.

And 1876 is generally regarded by SABR as being the first year of professional baseball. So, according to Baseball Almanac, between then and now, more than 19,700 players have appeared in a major league game.

“That’s an exclusive club for sure,” Quantrill said with a laugh.

“But,” Quantrill continued after a pause, “we all know it’s about more than just numbers. There’s almost a romanticism about it.”

Indeed.

Fathers and sons and a baseball and a glove and a bat. It doesn’t matter if it’s in the backyard, or the local park, or in a custom batting cage. It doesn’t matter if the ball is hit off a tee, thrown underhand or served up as a nasty curveball. It doesn’t matter if the sound comes in the form of the thump from an oversized plastic bat, or in the form of the ping from aluminum or the thwack of wood.

It’s baseball, and it’s fathers and sons. Nothing better.