In one of those old-time photos from a bygone era, there is a picture of the 1938 New York Yankees -- including such immortal legends as Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Bill Dickey.

Eighty-four years later, the name George Selkirk might not be as recognizable to Yankees fans as the first three -- all of whom had their numbers retired and are memorialized in Monument Park. But by all accounts, and by all metrics, Selkirk had a stellar career in pinstripes.

The Canadian-born outfielder made two American League All-Star teams, hit .300 or better in five of his nine big-league seasons and appeared in six World Series, winning five of them. His Major League debut in 1934 -- when he was called up to the Yankees after seven years in the Minors -- is still remarkable: 38 RBIs with 13 extra-base hits in just 46 games and 192 plate appearances.

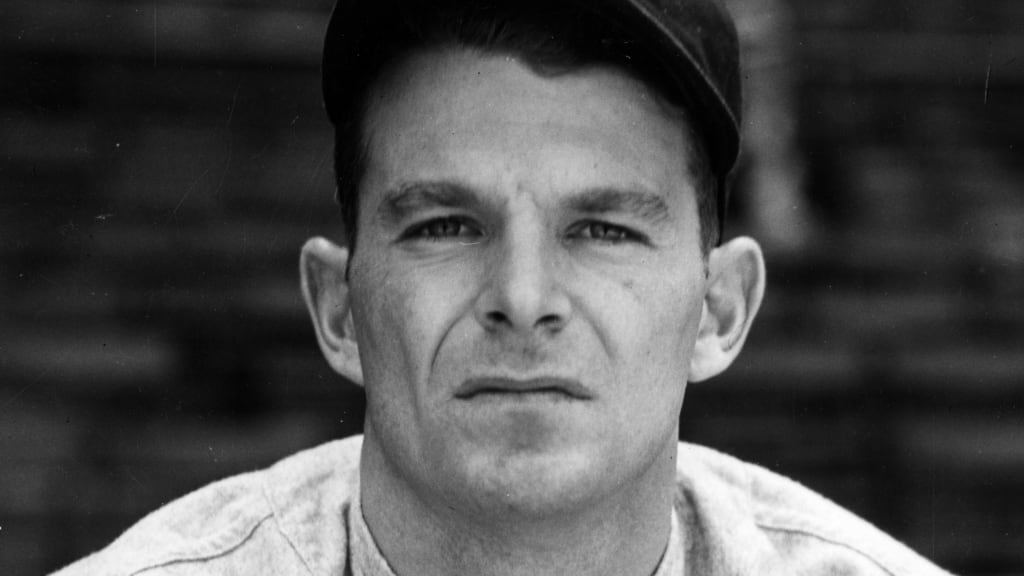

Yet, in many ways, George Selkirk is the forgotten New York Yankee. Some people look at that black-and-white picture, and at the guy next to Dickey staring straight into the camera’s lens, and say, “Who’s that?”

Well, that’s the guy who replaced Babe Ruth, following in Ruth’s footsteps in right field and even wearing the same uniform No. 3.

Selkirk was the guy who helped rekindle the Yankees’ dynasty.

***

Throughout the course of history, the sports world has been littered with players and coaches who took over for legends and were unsuccessful. Some failed due to circumstance -- they were good, but never quite as good as the deity they replaced in the eyes of fans. And some failed because of, well, reality -- they were never really quite talented enough for the ultimate level of sports competition.

George Alexander Selkirk was neither. He was better than good, he deserved his spot on the Yankees’ roster, and he was a key cog in helping to continue to forge the dynasty built in the Bronx during the 1920s.

That’s who he was. As for who he wasn’t? Well, he wasn’t Babe Ruth.

Then again, who was?

Ruth transfixed a nation at a time long before television and satellite and social media. His legend grew through radio and newspaper and magazine accounts. It was not only his talented exploits as a pitcher and a hitter, but also his charisma and outsized personality -- which came bursting through the screens at movie houses across the country courtesy of the short news reels that played before the main feature -- that earned him the adoration of millions.

He was The Babe. The Great Bambino. The Sultan of Swat. The Colossus of Clout. The King of Crash.

He was larger than life.

And George Selkirk knew it.

He knew all about Ruth and Gehrig and Frankie Crosetti and Tony Lazzeri and all the players on a loaded Yankees roster that left little to no room for Minor Leaguers hoping to earn a shot.

It took a veritable act of the baseball gods for Selkirk to finally get a taste of the big leagues at the age of 26, a time when most Major Leaguers are well into their careers. In late July of 1934, Yankees left fielder Earle Combs was racing to track down a well-hit ball in a game against the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman’s Park. Combs’ momentum carried him full speed into the concrete wall, leaving him with a fractured skull. His season was over.

Selkirk’s career was about to begin.

The outfielder was called up from the Yankees’ farm team in Newark, New Jersey, where the left-hander was batting .357 for the Bears. It took him almost three weeks to make his debut, but he finally was inserted into the lineup on Aug. 12, 1934, and he closed out the season with the aforementioned impressive flourish.

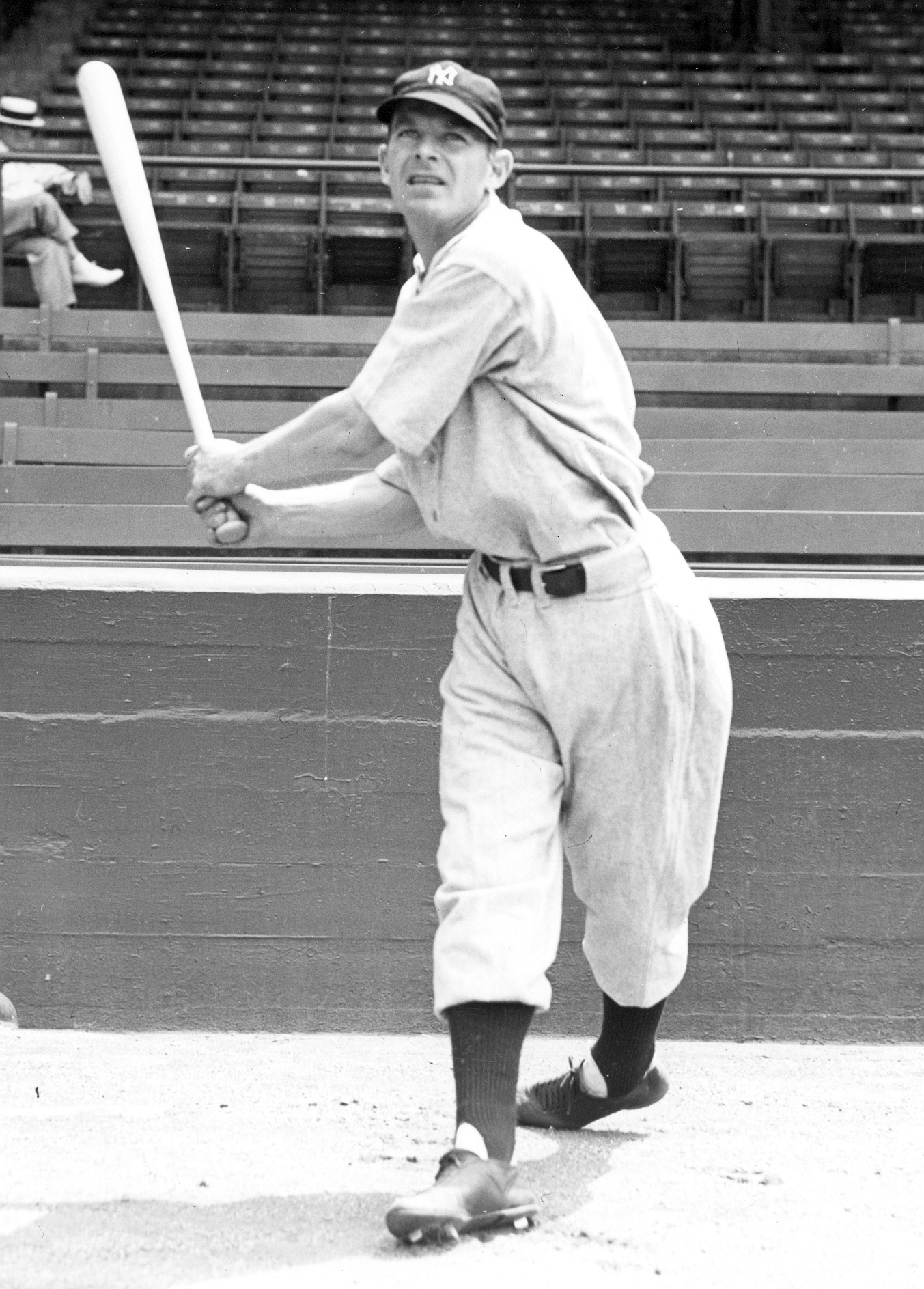

Selkirk was a Yankee and was there to stay, endearing himself to his teammates so much that they co-opted a nickname from his Minor League days and began calling him “Twinkletoes” for his unique running style.

“When I was a kid, I had a lot of trouble with charley horses and stuff. A coach by the name of Spike Garnish told me if I would run on my toes, I might get over it,” Selkirk told Yankees Magazine in 1983. “So, I did. Not only made me faster, but cleared up the leg trouble. [Sportswriter] Ernie Lanigan pinned the label on me when I was with Jersey City. The name stuck.”

Selkirk played the last five weeks of the ’34 season with Ruth, including Ruth’s last game as a Yankee against the Boston Red Sox when The Babe played right field and Selkirk was in left. The Yankees released Ruth prior to the 1935 season, and he signed with the Boston Braves, lasting only until May before he retired.

In the meantime, as the ’35 season opened and the familiar site of Ruth in right field was gone, boos rained down on Selkirk. But he was prepared for the reception. And the boos were short-lived, in part because of Selkirk’s confidence.

“If I am going to take his place [in right field], I’ll take his number, too,” Selkirk told the Brooklyn Eagle in 1936.

Indeed, Selkirk came out for the first game in ’35 wearing No. 3 and proudly wore it for eight seasons.

“Instead of being just another outfielder, one who was no Tris Speaker or Earle Combs in the outfield, I was expected to make the fans forget all about one of the greatest players in the history of the game, Babe Ruth,” Selkirk told the Eagle.

Yankees manager Joe McCarthy later told the authors of Lefty: An American Odyssey that Selkirk was one of his favorite players.

“George was under heavy pressure that first year, but he came through brilliantly,” the manager said. “No player ever had a tougher assignment.”

Selkirk had an outstanding rookie season in 1935, especially given the circumstances. He batted .312, hit 11 home runs, 29 doubles and drove in 94 runs, second on the team only to Gehrig’s 120. The Yankees finished three games behind the eventual World Series champion Detroit Tigers.

Selkirk had arrived, and it wasn’t just as Ruth’s replacement or as a spark plug. He was a vital part of the Yankees engine that appeared in the 1936, ’37, ’38, ’39, ’41 and ’42 World Series during his tenure in the Bronx, winning all of them except the last. He batted .290 overall, .265 in 21 postseason games, and he was an American League All-Star in 1936 -- playing alongside rookie center fielder DiMaggio -- and again in 1939.

In fact, his first All-Star campaign often gets overshadowed by the great 1927 Yankees, but the 1936 Yankees won the American League pennant by a whopping 19 1/2 games with a 102-51-2 record and had five players -- including Selkirk -- drive in 100 or more runs. Selkirk led all American League right fielders in fielding percentage that year as well.

Selkirk made his name playing baseball at Rochester Tech in upstate New York as a catcher, but he was born in 1908 in Huntsville, Ontario, before his father relocated the family of five to America and they became U.S. citizens.

He was originally signed by Rochester of the International League in 1927, but when he heard a team in the Eastern Shore League needed a catcher, he jumped at the offer. The Yankees eventually purchased Selkirk’s contract, starting him on his journey to crack the star-studded big-league roster.

In addition to Ruth, Selkirk is also inextricably linked to another famous Yankee from that era -- Gehrig. According to a story in Canada’s National Post, Bill Hine, Selkirk’s son-in-law, said his famous father-in-law would share a hotel room on the road with none other than the Iron Horse. The two players had an affinity for wrestling -- another sport Selkirk competed in at Rochester Tech — but the freakishly strong Gehrig often got the better of him during their playful hotel room matches.

“They rassled and rassled in a hotel room because hotels in those days didn’t have much to offer in the way of a workout room,” Hine told the paper. “Lou was stronger. Lou was winning most of the matches, even though George was well configured and was a man that kept in shape. He didn’t put on pounds. I never saw George looking like a businessman. He always looked like he was an athlete.”

Until one day.

“One day, Lou all of a sudden went limp. George didn’t want to hurt him,” Hine said, noting that his father-in-law quickly backed off.

“Lou, what’s wrong?” Selkirk asked Gehrig.

“I don’t know,” Gehrig replied.

“Lou professed innocence,” Hine said. “He just didn’t know. That was the start … a sensitivity that something was wrong.”

The something, of course, was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Gehrig voluntarily ended his consecutive games streak at 2,130 on April 30, 1939, and retired from baseball on July 4, 1939, when he delivered his famous “Luckiest Man” speech at Yankee Stadium. He died on June 2, 1941.

By that point, Selkirk had become more of a reserve player. In 1943, he enlisted in the United States Navy and served in World War II. But after coming home in 1946, he still lived a baseball life. Selkirk managed in the Yankees’ farm system for several years, and in 1953 he joined the Milwaukee Braves organization and was named the American Association Manager of the Year.

Selkirk then worked as a player personnel director for the Kansas City Athletics and helped bring in a young right fielder who also eventually made his way to the Yankees and was mentioned in the same breath as Ruth -- Roger Maris, whom Selkirk acquired from Cleveland in 1958.

“He could have used another season in a top Minor League to get the experience he needs,” Selkirk told John E. Peterson for his book, The Kansas City Athletics: A Baseball History 1954-1967. “But there is no telling how far he can go. He has all the tools to be great.”

One of Selkirk’s greatest contributions to the game came during his playing days. Recalling Combs’ injuries running into the wall at Sportsman’s Park that paved the way for Selkirk’s promotion to the Majors in 1934, Selkirk was chatting with reporters midway through the 1935 season when he made an observation. There should be a cinder path, he mused, about six feet from the outfield wall. Such a path would let an outfielder know that he had left the soft, silent comfort of the grass and now had something crunching under his feet, a signal that he was close to the outfield wall. Major League Baseball took Selkirk’s suggestion and implemented what is known today as the “warning track” in 1949.

Selkirk died in 1987 at age 79 and was deservedly inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983, as well as the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame in 2005. He will forever be remembered as the man who replaced the greatest baseball player in the history of the game, but his belief in himself ensured that he is no mere footnote.

“Did I worry? Well, I tried not to,” Selkirk told the Brooklyn Eagle more than 80 years ago. “Ruth, you know, had always been my baseball hero, but never had I thought I would be taking his place.”