We lost Jerry Remy on Saturday to lung cancer, which he had fought for 13 long and valorous years. Dave O’Brien, the last play-by-play man with whom Remy worked, lost a partner, as did Dennis Eckersley, with whom both Remy and O'Brien always had so much damn fun. But it was more than that with Remy's passing, at the age of 68. This was a profound death in the Boston Red Sox family.

O’Brien talked on Sunday about the way Remy fought cancer, for as long as he did.

“He used all of his bullets,” O’Brien said.

He sure did. No one said it at the time, but when Remy stepped away on Aug. 4, there was a sad, empty feeling for those who knew him or had ever listened to him do Red Sox games for NESN that this time he would not be back.

Even with that, Remy got one more fine night at Fenway Park, where he spent so much of his adult life. The kid who was born in Fall River, Mass., and grew up in Somerset finally ended up playing for the Sox, before he became as beloved a broadcast figure as the Red Sox ever had. Boston brought him out to throw the first pitch before this year’s American League Wild Card Game on Oct. 5 between the Red Sox and Yankees at Fenway, 43 years after Remy got two hits against the Yankees in the famous one-game playoff between those two teams, what will always be known as the Bucky Dent game, on Oct. 2, 1978.

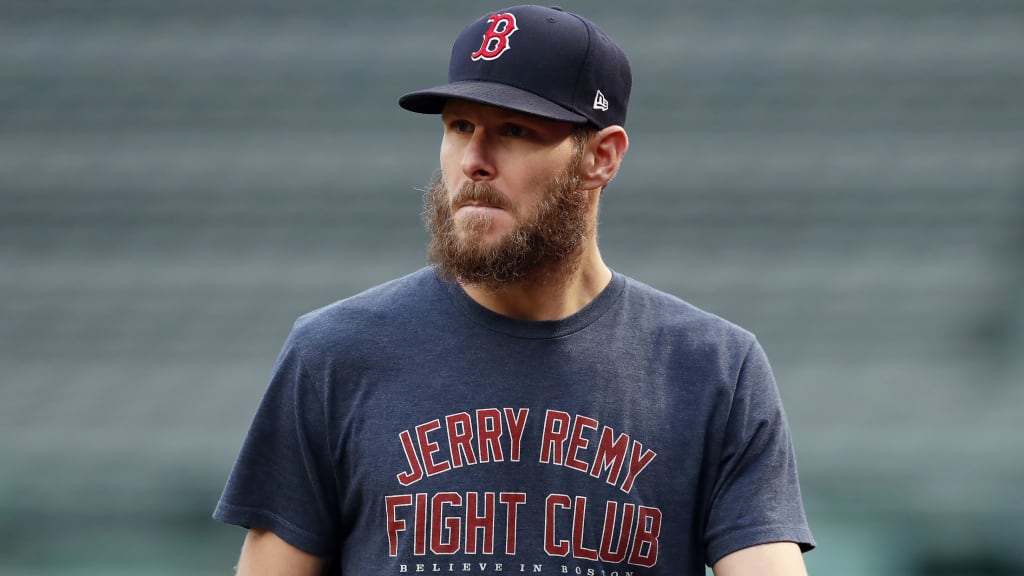

Remy was there to throw the pitch and Eckersley was there to catch it. Then the two men embraced and there was one more Fenway ovation for Remy, the man whose fight against cancer had inspired Red Sox players, coaches and manager Alex Cora to proudly wear “Jerry Remy Fight Club” T-shirts as he went off to battle his disease for the last time. And in that moment, as sick as he was, in the ballpark that became both his office and his second home, he smiled and looked young.

“One tough son of a gun,” O’Brien said as the baseball world was in the first stages of mourning Remy. “It was a privilege to sit next to him.”

Every Red Sox announcer who sat next to Remy understood the power of his connection to Boston fans -- maybe because he was one of their own, the tough son of a gun who became a dirty uniform and a very tough out playing second base for the Sox after they got him from the Angels and brought him to Boston where he belonged.

Of course every baseball fan understands the power of that connection to their team’s broadcasters, whether on the radio or on television. They do become family. They come into your house in Spring Training and don’t leave until October. There is no relationship in any sport that is like the relationship between fans and their hometown announcers, because of the beauty and length of the baseball season. It was just a little better and a little different with Remy in Boston, because fans of the Red Sox knew he was one of them. He was one of their own until the day he died, and he took all of that Red Sox history and all of the fun he brought to the broadcasts with him.

I’ve written this before: There was no better listen in baseball than O’Brien and Eck and the man known as the RemDawg, who was first drafted by the Angels exactly 50 years ago. That was the beginning of a wonderful baseball life that did not end until the Red Sox had made one more October, one he briefly shared with them with that first pitch to Eck before the Wild Card Game.

Remy was a private man who became such a visible public figure in Boston one baseball season at a time, and he was as smart a broadcaster as he had been a player, one who played 10 years in the big leagues and ended up with a lifetime batting average of .275, including having twice hit .300 for the Red Sox. Remy used to joke constantly about having just seven career home runs in those 10 seasons.

“I can take you through them if you want,” he joked one day at Fenway when I’d gone into the broadcast booth he was sharing with O’Brien to say hello. “It won’t take long.”

He was the RemDawg to the end. He was the Red Sox fan who played for them and then broadcast the games, so many of them informed at the end by lung cancer. You just never heard that on NESN, ever.

“There’s going to be a void when I look over that way and he’s not there,” O’Brien said on the phone Saturday afternoon. “I’ve spent half the day in tears. But then I’d hear him telling a story, usually on himself, and then I’d be laughing my butt off.”

O’Brien was not alone in Red Sox Nation on this day. There will be an empty seat next to him from now on, and empty seat in the living room of everybody who cares about the Boston Red Sox.