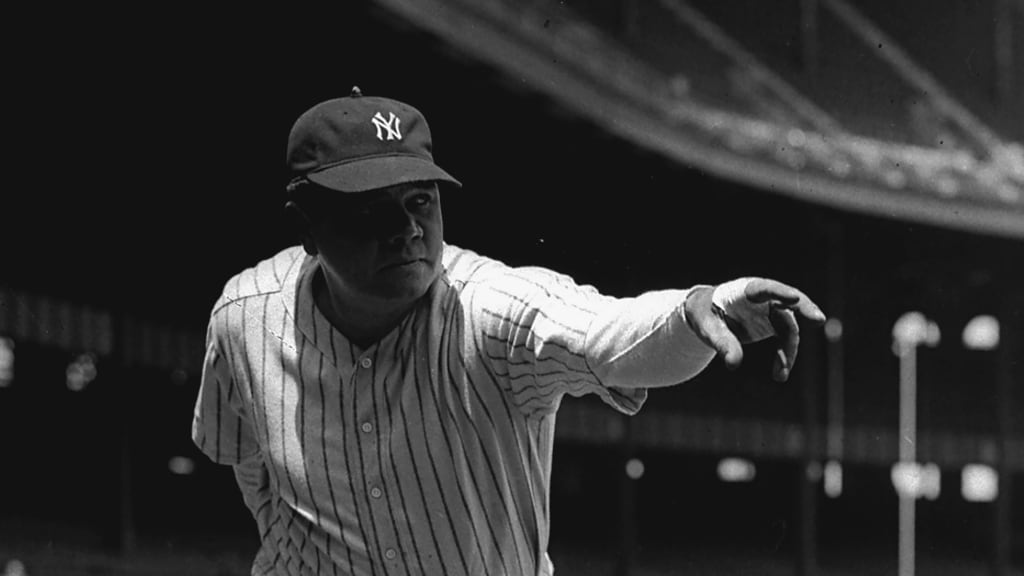

The crowds piled into giant Almendares Park -- excited to see the baseball folk hero they'd only read about in newspapers. The greatest home run masher in the world.

Could he actually be real?

Could there actually be a person who hit 54 homers in one season? Somebody who had the ability to reach distances of 580 feet -- a human who seemingly deposited the ball over fences at will?

Those were the thoughts and words and whispers swirling around Havana's cavernous stadium in the winter of 1920, as the great Babe Ruth arrived for an exhibition series against a couple of local teams.

“[Ruth’s] feats were touted in the papers,” Roberto González Echevarría said in his book "The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball." “But Cuban baseball was not home run centered. Black baseball was very prudent, very tactical."

"[Cuban baseball] was more of a hit-and-run, steal bases, move-runners-along type of game," USA Today writer and Cuban baseball historian Cesar Brioso told me over the phone. "And it really was that way for quite a while."

But, quite unexpectedly, Ruth's thunder was stolen.

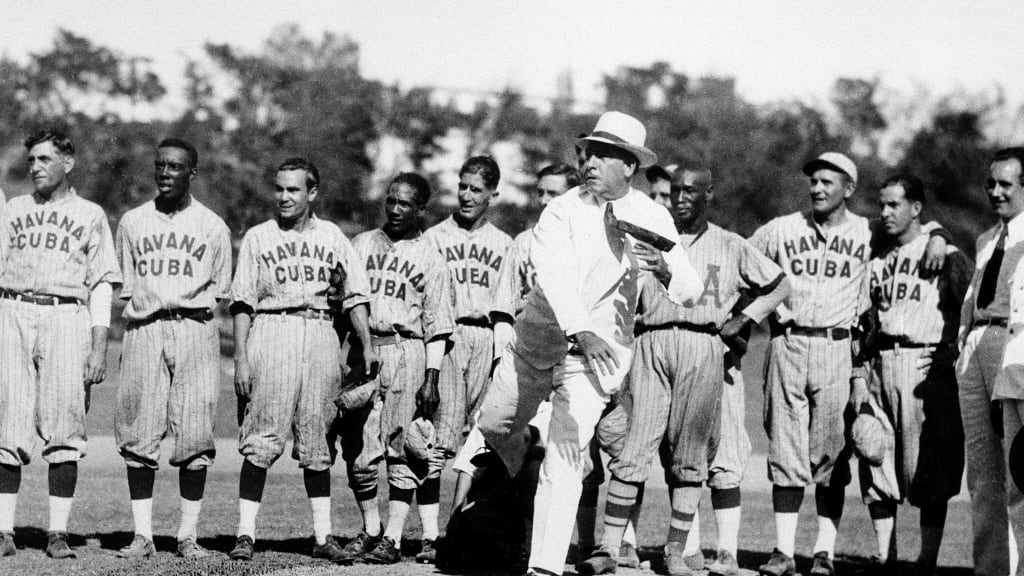

A local legend, one whose own mythical tales rivaled the Great Bambino's, overshadowed the famous guest. A five-foot-10, five-tool center fielder who was said to wield the skills and power of entire ballclubs. A man whose ground balls left craters in the Earth's surface.

The great Cristóbal Torriente.

Although many facets of Torriente's life and career are underreported, the parts that are available suggest he was one of the all-time great hitters in the sport.

He holds the highest career batting average in Cuban League history at .352 -- reaching as high as .402 one season. He had a rocket arm and blazing speed. He played in the Negro Leagues starting in 1920, putting up an astounding .411 average in his debut with the Chicago American Giants. He had a 1.000 OPS in four of his nine seasons in the NNL. He joined the famed Kansas City Monarchs for one year in 1926 and easily led the team with a .351 average and .446 on-base percentage. His Negro Leagues WAR is third all-time -- ahead of Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell. Unfortunately, because of segregation, Torriente never got the opportunity to show his stuff at the big league level.

"He's a member of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame -- getting in with the inaugural class," Brioso said. "He's one of the giants of the first half century of the Cuban League and Cuban baseball."

And for this 10-game series in 1920, Torriente was playing for the Almendares Blues -- a team he starred on for many seasons in Cuba. Ruth was in town with John McGraw's New York Giants, getting $20,000 to go down and impress fans who'd never seen him in person. Dinger warnings were put out all over the Atlantic.

“Babe Ruth is playing winter ball in Cuba,” read the Daily Illinois. “Reports have it that boats going from the U.S. to Havana are putting on armor plates to escape being torpedoed by stray homers.”

The hype captivated the entire island.

But in the 10 games against Almendares and Habana, Ruth would only hit one long ball. Granted, it was a momentous blast out of the, at some points, 600-foot dimensions. From the "Pride of Havana:"

The Babe's blast went to the corner between the end of "sol" and the center-field wall or scoreboard. Mendoza says that it may very well have been the longest homer ever hit in Almendares Park; a rough estimate would be about 550 feet.

The Babe hit .345 with five runs and a triple in the series. Some fans began booing him, fully expecting the slugger to be able to hit one out every time he stepped to the plate.

Meanwhile, Torriente hit a blistering .400 and clubbed four long homers in 35 at-bats against the Giants. As mentioned before, even his grounders left impressions on the Giants' fielders.

“I was down in Havana in 1920 with Babe Ruth and about 12 of the New York Giants,” Frankie Frisch said. “That’s over 50 years ago, but I can still recall Torriente. I think I was playing third base at that time, and he hit a ground ball by me, and you know that’s one of those things – look in the glove, it might be there. But it wasn’t in my glove. It dug a hole about a foot deep on its way to left field. And I’m glad I wasn’t in front of it!”

But there was one game that stood out from all of the others: On Nov. 6, in an 11-4 Almendares blowout win, Cienfuegos' native son captivated the crowd with three homers. Three-homer games rarely occurred in the Major Leagues at the time and likely never happened in any of the Cuban League confines.

"When Dick Sisler came [to Almendares] and played there in the '45-46 season, he hit three home runs in a game and he was hailed as this hero," Brioso told me. "They actually had a Dick Sisler Day to commemorate the event."

Some accounts say Torriente's blasts went over the fence, while some suggest they just went over the outfielders' heads and the speedster raced around the bases for an inside-the-park homer. Either way, the Cuban crowds -- mostly there for Ruth -- couldn't get enough of Torriente. They threw cash, change and gold watches onto the field. They presented him with 400 cigars postgame.

"Yeah, in that game it was three, and Ruth had zero," Brioso said. "And that was the big deal, right? It's got all those David vs. Goliath elements. The hometown kid outperforms the great Babe Ruth."

And Torriente even faced off -- one-on-one -- against the Bambino.

Along with being a tremendous slugger, Ruth was, of course, a very accomplished pitcher. His last semi-full season on the mound was in 1919 -- when he put up a 9-5 record and 2.95 ERA. McGraw brought in the Babe from center field to try and stop the Almendares' onslaught during the Nov. 6 game and, after retiring the side in one inning, he faced Torriente with two men on during the next. Here's more from the book, "The Bambino Visits Cuba, 1920" by Yuyo Ruiz:

The Babe and Torriente exchanged glances, apparently trying to conceal a smile according to El Mundo reporter Victor Munoz, but they did not exchange words. On Ruth's third pitch, Torriente's bat broke the ice, sending a ball screaming into the gap between left and center field. Torriente reached second on the hit that drove in two more runs for the Cubans and Ruth was sent back to center field ...

"Torriente Steals the Show from the Babe!" read the next day's newspaper headlines.

From El Dia newspaper:

Yesterday, Cristóbal Torriente elevated himself to the greatest heights of glory and popularity. His hitting will enter Cuban baseball history as one of its most brilliant pages.

And El Heraldo de Cuba:

Ruth could produce nothing worth mentioning in the game that saw Torriente shine.

Now, as some accounts mention and Brioso brings up, there were a couple things that might've dampened the impact of Torriente's dominant performance.

First, Torriente did most of his damage that game against High Pockets Kelly, a position player who pitched a total of three games in his career. Second, there were reports that the games were set up more like batting practice and teams weren't taking the games seriously. It was more of a vacation for the big leaguers than anything else.

Brioso pushed back a bit on this idea, citing a time when McGraw took a team down in 1911 that lost to Havana. McGraw had fined one of his players for taking full advantage of the Cuban nightlife and not playing to his potential. He was extremely angry he lost to these non-MLB players.

"Sometimes maybe some of these players may not have taken it too seriously in these exhibition games," Brioso recalled, "but there's an element of pride when you start losing to what you consider to be inferior talent."

These were competitive professional athletes, John Holway even wrote of how "the Bambino frowned incredulously" when Torriente slid into second after hitting the double off him. The 1920 performance even helped get Torriente into the National Baseball Hall of Fame back in 2006: His outplaying of one of the game's most prolific hitters is highlighted in the last line of the plaque.

As Ruth once said himself:

“Tell Torriente and [José] Méndez that if they could play with me in the Major Leagues, we would win the pennant by July and go fishing the rest of the season.”