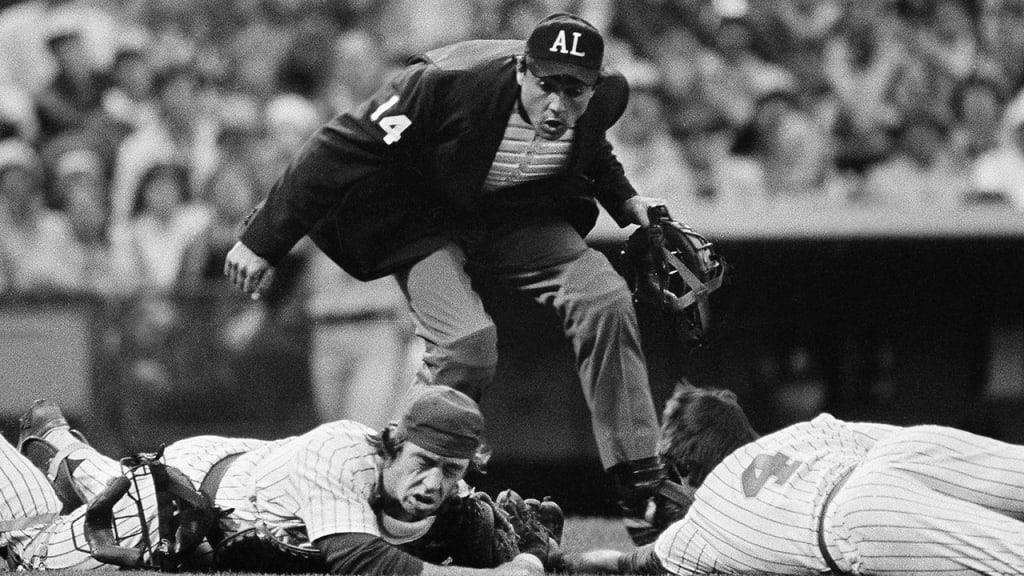

KANSAS CITY -- There was so much sadness at the end. Steve Palermo was born to be an umpire. It was his fate, his destiny, the thing he felt sure that he had been born to do. Then he became a big league umpire, the best umpire, an artist of balls and strikes, a perfectionist who knew his business.

"Strike!" he said.

"Where was that pitch at?" Yankees batter Lou Piniella shouted.

"Why, Lou," Palermo said, "I would think an educated man like yourself would know that you do not end sentences with a preposition."

"Fine," Piniella barked. "What was that pitch at, you $#%$%@?"

Yes, it was beautiful, an umpiring career destined for Cooperstown. Stevie loved all of it, the epic verbal cage matches with Earl Weaver (who Palermo would not call by name for the rest of his life), the practical jokes, the sound of the crowd, the crazy plays and … well, there was this one time with a rookie pitcher named Curt Schilling. Actually, we'll get back to that one.

You probably know that umpiring ended too soon for Stevie. In 1991, he was in an Italian restaurant in Texas -- it was always an Italian restaurant for Steve Palermo -- and someone shouted out about two women getting mugged across the street, and he never thought twice. He and two friends ran into the street, shots echoed in the night, and a single bullet struck Steve Palermo in exactly the right or exactly the wrong place depending on your point of view.

The bullet was a millimeter or two away from hitting an artery and killing Steve.

The bullet was also a millimeter or two away from missing his spinal cord. It did not miss. Palermo immediately lost feeling in his legs. Doctors told him he would never walk or umpire again. He proved them wrong, he did walk -- it took heroic effort and endurance of unimaginable pain. He walked. He played golf. He raised millions of dollars for spinal cord research. He worked in baseball again. Steve Palermo was impossibly tough, impossibly dedicated, a fighter.

But he never did umpire again.

That was the agony. He had his destiny taken away from. He hid that sorrow mostly for the last 26 years of his life, hid it behind his joyous smile, but it was there. "I miss it," he told me once. "I just miss being out there. I don't miss the World Series and the playoffs and all that. I miss the feeling of being out there, the way it sounds on the field, the way players talk, the feeling. My wife says sometimes, 'You miss the jazz.' She's right. I miss the jazz."

Those years after Texas were hard, but there was a lot of joy in them too. Steve and his wife Debbie, they made the best of it, they traveled, they had a million friends, they brought so much happiness to people around them. You just loved every chance you had to be around Stevie and Debbie; they were perpetually young and alive. Stevie worked in baseball again, an umpire supervisor, and he loved that, he worked on ways to speed up the game, worked on ways to make his umpires better (and he defended those umpires to the end, too).

The last four years, though, even that was sapped away. The pain kept coming in waves. And then there was the cancer. He never stopped fighting because that was Stevie's nature. But some fights, you can't win.

"I didn't quit," he told Debbie at the end. "I just ran out of time."

He died on May 14, six weeks ago.

There was so much sadness at the end, and that's why Monday was beautiful. Debbie did not want a memorial for Steve Palermo. She wanted a celebration. That's why she waited time for some of the sadness and shock to dissolve.

And Monday, at the beautiful Kauffman Performing Arts Center in downtown, we celebrated Steve Palermo. Bob Costas, one of Palermo's dearest friends, told stories. Bob Uecker, another buddy, told jokes. Umpire Joe West, Hall of Fame third baseman George Brett and longtime football executive Carl Peterson quickly brushed away tears as they spoke, because this wasn't a day for tears. Stevie would not have wanted tears.

"Debbie said she wanted laughs," Costas told the crowd. "And we should laugh."

And there were laughs, as people remembered Palermo's giant dog. "He doesn't bite," Palermo used to say, "And if he does, he doesn't bite hard." People remembered the way he used to blow bubbles between batters, the back-to-back games he threw out Weaver (one for a balk call, the next for a non-balk call) and his refusal to back down. ("Remember when you yelled at me about that strike call?" he once said to Brett. "Well I looked at the video. And I was right.").

In the end, this gathering of friends stood and applauded, a sound umpires never really hear. It always seemed to me that Steve Palermo was a true American hero, and it wasn't because he went out that night to save people. That was what got him on the cover of Sports Illustrated, and featured on Nightline. It's why he received a letter from President Reagan.

But the heroism -- yeah, that was in how he lived after that, all those years, how he inspired so many people, how he refused to let the unfairness of it all steal his spirit.

Nobody told the Curt Schilling story on Monday, but it's one of my favorites. In 1988, when Stevie was whole and felt like the luckiest man in the world, he was behind the plate for Schilling's big league debut. Do not think about Schilling as he is now -- however you feel about him -- but as he was then: 21 years old, a little bit cocky, a little bit scared. It was just eight months after his father Cliff died, the man who had instilled the baseball dream inside Curt (Cliff put a baseball glove in his son's crib).

Steve Palermo saw a lot of young pitchers debut. He saw a lot of old ones exit the game. He was an umpire. But he was more than that.

"How ya doin' kid?" Palermo asked Schilling as he walked out to the mound before the game began. Schilling looked green.

"Kind of nervous," Schilling said. He was shaking so hard he could barely get the words out. Schilling would someday become the greatest postseason pitcher of his generation. He would pitch with blood coming out of his ankle. He would strike out 3,000 hitters. He would infuriate and galvanize. But in that moment, he was just a kid facing a moment that seemed too big. And his father was not in the stands to see it.

"Tell you what," Steve Palermo said. "You just get that first pitch close, I'll call it a strike, and we'll get this game going."

Schilling nodded. He never forgot that moment; he told me that story more than 15 years later. The first pitch Schilling threw was to Wade Boggs. It was a strike … or at least Palermo called it one. And the game got going.