Francisco Lindor got traded to the Mets last winter, signed a $341 million contract just before Opening Day and then immediately got off to one of the worst starts in Mets history.

No, really. In his first 43 games, a span so chosen because that's when his season bottomed out, he hit .185/.290/.268. Only seven Mets have ever done worse in their first 43, and you don't really want to be on a list with Argenis Reyes or Roy McMillan.

Lindor's April was so weak that it was the worst full month of his entire career. If his May was slightly better, it was only by a matter of degrees, because the .637 OPS he posted was merely the third-worst month of his career. Even now, coming up on the All-Star break, the season line is disappointing: .217/.309/.365, a 90 OPS+. He’s hit, believe it or not, just like Amed Rosario, the former Mets shortstop who went to Cleveland in the trade.

He will, almost certainly, end up with the weakest first half of his career, aside from the truncated 2015 that began with his June promotion to the Major Leagues. Yet we come today not bearing the doom and gloom, because if you’re a Mets fan, you’ve already lived through all that. We come to point out that despite the lousy overall line, it’s actually getting a whole lot better …

April: .542 OPS

May: .637 OPS

June: .837 OPS

... to the point that June is actually one of the 10 best months of his career.

It might not feel like it, because the season line still doesn't look great. So what's going on? How did we get here, and more importantly, are Lindor and the Mets through the bad times? The answer might determine just how far this team can go.

What went wrong?

In order to figure out what’s going right, we need to figure out what went wrong, don’t we? We’d like to say there’s an easy answer to this, but really, none of this is going to be easy. If it was frustrating to watch in real time, it's just as painful to reconstruct after the fact.

Here’s the first problem: A lot didn’t go wrong. At least that we can see through stats; if there was some adjustment period not only from the trade away from Cleveland but also due to the weight of the hefty contract and the early-season booing from Mets fans, well, that would be easily understood. (Blake Snell, who has struggled this season in San Diego, openly talked about how hard it was for him to leave Tampa Bay recently.)

Still, few of the obvious warning signs show up in the metrics. Lindor didn’t really strike out more in the first two months of the season. His hard-hit rate wasn’t down. He didn’t walk less, he walked more. These are the first things you look at, and there was just nothing there. It’s not about his home/road splits, or even his lefty/righty splits, at least in the sense that “they were all bad.”

So your natural inclination is to go to "bad luck," and when you have someone as decorated as Lindor hitting .198 through two months, there's probably a little of that, sure. If you were to look at his .220 Batting Average on Balls In Play through the end of May (i.e., "batting average without the homers") and compared it to the .271 expected average based on the quality of his contact, you'd say that sounds like a lot of missing hits, but also that's not an uncommon thing to happen over the first few weeks of a season, either.

On June 1, Ben Clemens of FanGraphs noted that Lindor was missing out on some luck on some weakly-hit balls, and pointed out that he wasn't getting all the production you'd expect when he did hit the ball hard. Clemens also accurately concluded that, "I’ll level with you ... I can’t figure out why this is all happening at once," and "maybe the answer is that Lindor is just a little off his game and a little unlucky at the same time."

So we’re starting with a mystery, to some extent. We’re not done yet.

Here’s the second problem: The best number we can point to to explain his positive change goes directly against what Mets manager Luis Rojas said he’d been trying to get Lindor to do.

“He doesn’t normally need to pull the ball,” Rojas said last week, in regards to his shortstop finding his power, after Lindor hit a home run just left of center field.

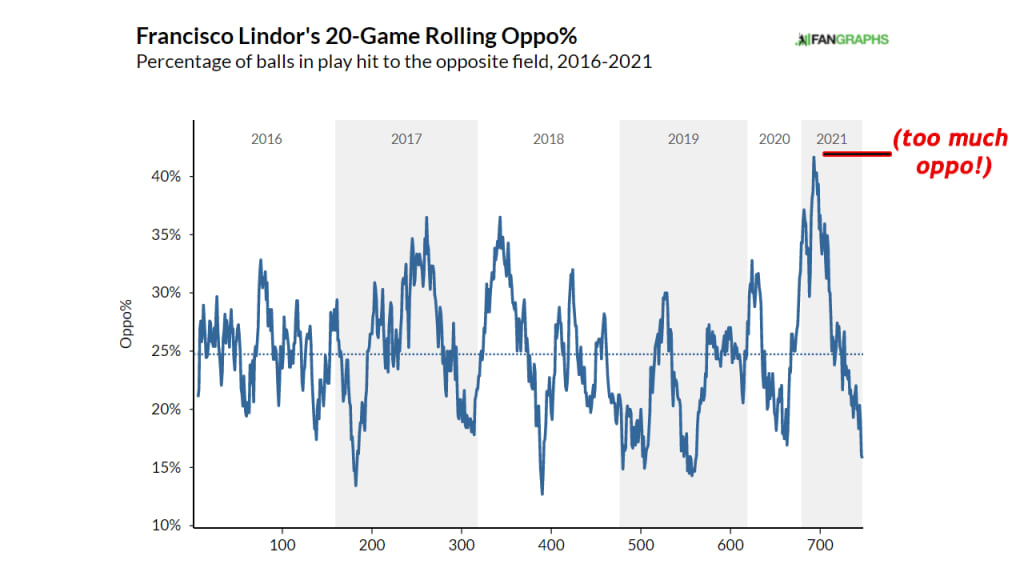

Perhaps not. Ideally, you don’t want to be a Chris Davis type of dead pull hitter, not unless you want to be completely eaten up by the shift. Yet we still can’t stop staring at this rolling chart of opposite field percentage from Lindor, because it just matches his early-season struggles so well. Remember when he said the first two months were two of the three worst of his career? April was the most oppo-heavy month he’d ever had. May was just outside the top 10.

June, for what it’s worth, is the third-least oppo month in Lindor’s career.

Lindor, like almost every hitter, is far less powerful to the opposite field, though in his case we’re talking about the fact that his hard-hit rate is cut in half going oppo.

Lindor's career hard-hit rate

Pull: 45.3%

Straight: 42.7%

Opposite: 22.1%

Think about it like this: In 2020-’21, Lindor’s pull/straight hard-hit rate was 80th of 435, or in the 82nd percentile. His opposite field hard-hit rate, meanwhile, was 176th of 225, or in the 22nd percentile. Completely unsurprisingly, for his career he’s hit .345 with a .613 slugging when going straight up the middle or to the pull side -- and that’s all batted balls, not sorting out weakly hit grounders. It’s good for him.

So some of his problem appears to be, simply, that he was doing less of the thing that leads to success and more of the thing that does not. Easy enough, right?

Except, there's another problem here. In April, when he was going opposite field more than ever, by all indications he wasn't exactly trying to do that.

Those are not exactly the kind of balls that you want to pull, which seems to point to his early season issues being a combination of "going oppo, which has limited utility," or "pulling the ball on the wrong kind of pitches," and while that didn't hurt his ability to hit it hard -- a 47% hard-hit rate on pulled balls in April, right near his career average -- half of them were on the ground.

Worse, there was plenty of indication that his swing was simply out of sync, as expertly broken down in early May by MLB Network's Mark DeRosa, a 16-year Major League veteran, who noted that Lindor's hips were opening too soon and causing the power from his swing to be mostly upper-body driven.

So, then, if we want to find the answer, we've got to solve these two problems. Did he fix the mechanical issues DeRosa outlined? And are the balls he's pulling now better ones on which to do damage?

"To get those types of results more consistently," MLB.com's Anthony DiComo wrote near the end of May, "Lindor has tried nearly everything. In recent weeks, he has focused on one-handed swing drills in the batting cage, in hopes of shaping his swing path closer to what it was from 2017-19 with the Indians -- his best offensive years as a big leaguer. He has tried to emulate his 2017 stance and swing in particular, but the difficult part has been rediscovering the feel of it. That indescribable element -- “feel” -- can often make a swing more than the sum of its mechanical parts."

Let's find out.

The swing seems like it might be different

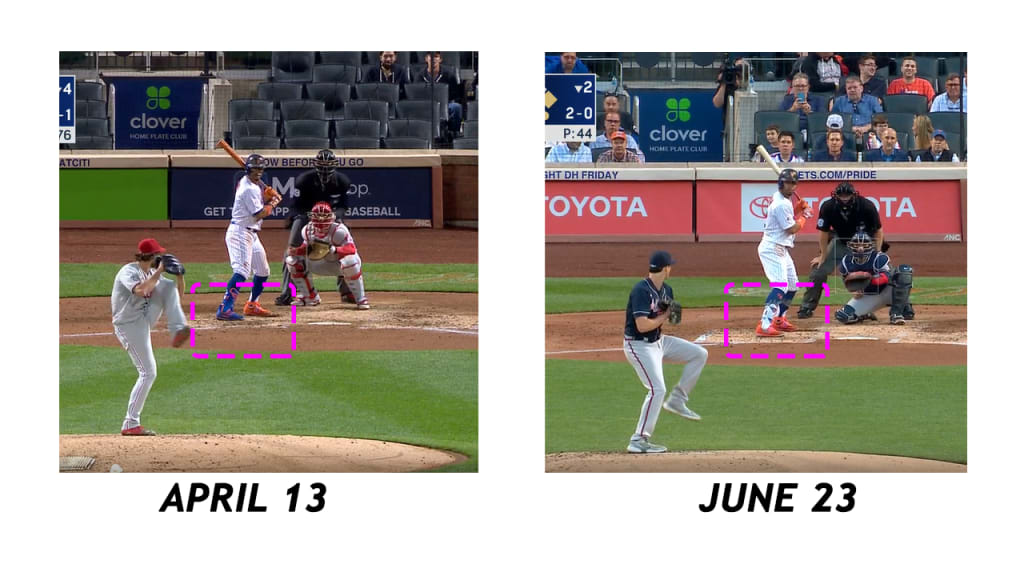

We are not swing doctors. Many an analyst has been led astray by a slightly different setup at the plate and thinking that's The One True Answer. But, since we have improved production in one pocket and DeRosa's breakdown in another, let's see what we can see. One thing seems clear enough; after starting the season in an open stance, he's more recently begun using a closed one.

There's evidence, too, that he's doing a better job of hitting the ball where it's pitched. In the first two months of the season, while batting lefty, when he hit a ball that came in on the outer third of the plate, he pulled it 35% of the time. In June, that's just 20% of the time. Conversely, he's taken those outside balls to the opposite field five times in the first three weeks of June after doing so only seven times in the first two months, while, remember, going opposite field far more. (It's similar, though less stark, hitting righty.)

And so, the end result of this seems to be some combination of comfort, of approach, of stance, of, as DiComo wrote, "feel." Lindor slugged a mere .243 in April, .344 in May and .500 in June. It's probably not right to say he's "back," necessarily, because the production has been coming in clusters -- he was 2-for-12 in between Saturday's two-homer day and Wednesday's homer -- but the trendlines are, at least, pointed up.

The truth, likely, is that the 2018 version of Lindor -- the one who hit 38 homers with a 132 OPS+ that he hasn't approached before or since -- is probably not coming back, because what looked at the time to be a full breakout from a 24-year-old ascendant star now looks like a career year. But he doesn't need to, either. So long as Lindor can be the regularly above-average bat he was in Cleveland, paired with what is still elite shortstop defense, he'll be worth the contract.

It can be done, anyway. When we said seven Mets got off to worse starts through 43 games than Lindor did, we joked about Reyes and McMillan, while glossing over the similarly doomed careers of Al Weis, George Altman, Frank Taveras and Bobby Pfeil. The worst all-time start to a Mets career, however, belongs to an infielder who went to high school in Florida and was traded from a Midwestern AL team, just like Lindor. In 1985, Howard Johnson didn't get his average over .200 until July 4. He'd end up hitting 192 homers as a Met, with an OPS+ of 124. It can be done.