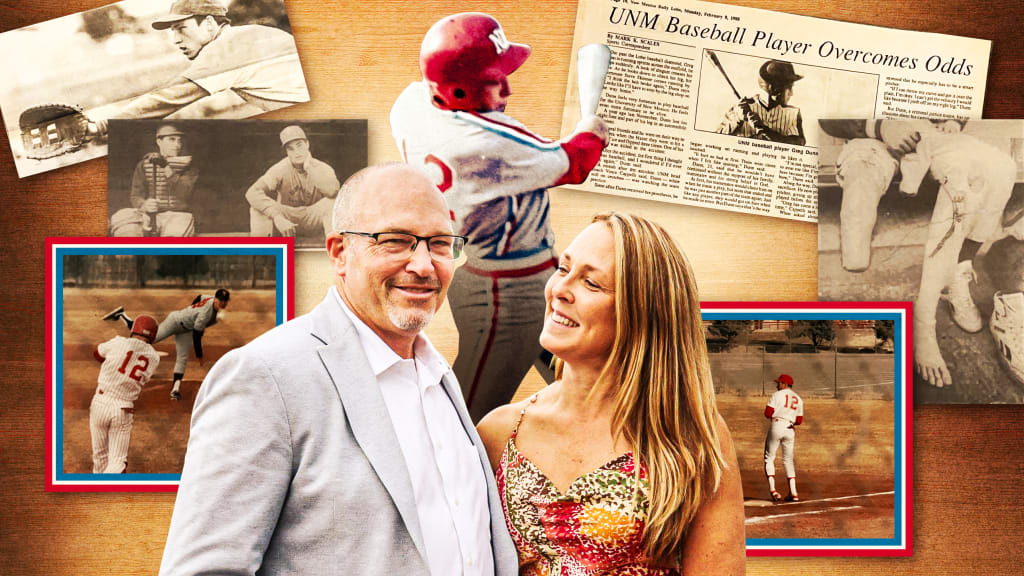

The article was shared with Greg Dunn, as it was shared with so many last month.

It was the inspiring story of an East Carolina sophomore named Parker Byrd appearing in his school’s season-opening baseball game with a prosthetic leg, after having part of his right leg amputated following a 2022 boating accident. The story originally noted that Byrd was believed to have been the first NCAA Division I baseball player to play with a prosthetic leg.

But when the story was e-mailed to Dunn, he knew that last part not to be true. Because he, too, had played Division I ball on a prosthetic leg and has his own inspiring story to tell.

“I used to say that I was just an average college baseball player but that I was the best one-legged baseball player ever in Division I,” Dunn says with a laugh. “But now I’m not, because of Parker. And I’m OK with that!”

One of Dunn’s former teammates at the University of New Mexico, where Dunn played on a prosthetic leg in the 1988 and '89 seasons, alerted MLB.com to his story. Dunn somewhat sheepishly agreed to tell it, despite not wanting to take any attention away from Byrd.

But let the record show that this amazing achievement has, indeed, happened twice.

“[Losing your leg] doesn’t have to be seen as a handicap,” Dunn says.

Dunn lost his leg on Nov. 21, 1986.

He was a sophomore at UNM and expected to be the Lobos’ starting shortstop in the 1987 season. He went on a ski trip to Colorado with some fraternity brothers. En route, on a windy highway in northern New Mexico, they came around a curve and hit a patch of black ice that sent their sport-utility vehicle rolling.

“I was in the backseat and had my seatbelt on,” Dunn says. “I was thrown out and went flying through the air. I woke up, and I was laying on my stomach, and the first thing I did was I tried to stand up, and my leg wouldn’t move. I looked down, and my leg was in a completely different direction.

“The first thing I thought was, ‘I’m not going to play baseball again.’”

The vehicle had landed on one of Dunn’s friends, killing him. The others in the vehicle somehow came out unscathed. With the blood pumping from his right leg, Dunn desperately needed a tourniquet. One of his friends wrapped a belt tight around his leg to stop the flow.

“I’m pretty sure that’s why I lived,” Dunn says. “I lost seven pints of blood out of 12. A friend of mine came and laid next to me, and we started praying. I had this experience, this feeling as though the Lord came and was with me, and, to be honest with you, my pain went away.”

Stranded in a remote area, it took hours for an ambulance to get Dunn to a nearby Native American reservation, where he remembers lifting his head to see a bone where his right leg had been. He then had to be driven to Farmington, N.M., to get the blood transfusion that kept him alive.

The first morning Dunn awoke in the hospital after having nearly half of his leg amputated, his UNM head coach, Vince Cappelli was there by his bedside, crying.

“You’re going to be a member of my team until you graduate,” Cappelli promised.

“OK, Coach,” Dunn replied, “then I’m going to play again.”

Dunn looks back now at that moment as a turning point.

“I had this person that truly loved me,” he said of Cappelli, who passed away in 2002. “He was really rough on the outside, but that coach loved me more than he loved baseball.”

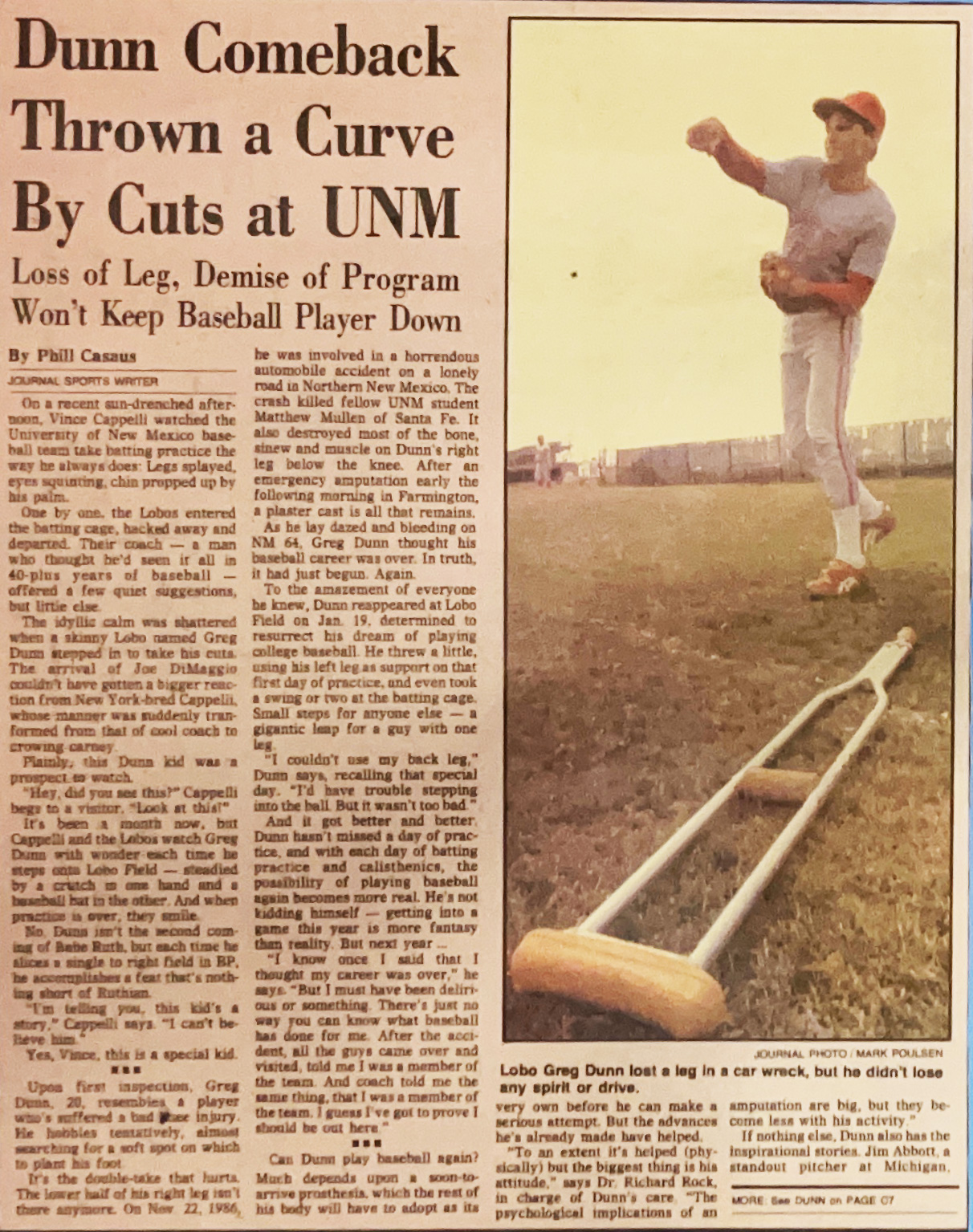

Dunn received a prosthetic leg a few months after the accident. And throughout the Lobos’ 1987 season, Cappelli would hit him ground balls an hour before practice.

Finally, in February 1988, Dunn defied the odds when he made a start at his new position -- first base -- for UNM in a game against Texas Tech. He went on to appear in 20 games that junior season and 41 in his senior season, compiling a .200 average (25-for-125). He specifically, fondly remembers a base hit off a Wichita State right-hander named Greg Brummett, who went on to pitch in the big leagues for the Giants and Twins.

He also remembers mixed reactions to his feat.

“I had some people on the team that were absolutely amazed and encouraged me more than you could believe,” he said. “And I had some really tough times with guys on the team that didn’t like the fact that a one-legged guy was competing with them for a position. I had some haters, to be honest with you.”

That Lobos team actually only existed because of the fundraising efforts of Dunn’s father, Tom, who had also played ball at UNM. Soon after Dunn’s accident, the school cut the baseball program.

“I told my dad that losing the program is worse than losing my leg,” Dunn said. “He went out and, through the community, raised enough money that they reinstated the program.”

That reinstatement allowed not only Greg Dunn but his younger brother, Reed, to play for the Lobos. The program remains intact to this day.

Interestingly, Dunn wasn’t the only member of his UNM teams to overcome physical adversity.

“It’s hilarious how it turned out,” he said. “My name was ‘Greg With One Leg,’ and we had a guy on the team named ‘Ty With One Eye’ and another guy named ‘Joe With No Toes.’ We used to crack up. And those guys were fantastic athletes.”

Athletes who, like Parker Byrd all these years later, didn’t let anything get in the way of pursuing their baseball dreams.

These days, the 57-year-old Dunn practices law in upstate New York, where he and his wife, Kirsten, raised nine (yes, nine) children and tended to a farm. He looks back fondly on his collegiate career.

And he roots for Byrd.

“I would just tell him to enjoy life, you know?” Dunn said of Byrd. “To appreciate the fact that God gave him this chance to play and to just try to enjoy it. That time of life goes by so quickly and, before you know it -- even if you’re two-legged -- your baseball career is over and done. You don’t stay a prime athlete for long. So I’d encourage him to just get some base hits and make sure his batting average is better than mine!”