Heading into the 2021 season, there are two important numbers you need to know: 540 and 1,458.

The first, 540, is the number of innings that teams had to plan for last year across 60 games. The second, 1,458, is the number of innings they'll have to cover this year across 162 games. That’s nearly three times as many, a massive increase from one year to the next. What do you do? What can you do? Those numbers aren't exactly the same for everyone -- you'll have a rain-shortened game here, an extra inning there, a seven-inning doubleheader across the hall -- but you get the idea.

No pitcher in 2020 threw more innings than Lance Lynn with 84. It was the first year in baseball history in which no pitcher threw at least 200 innings, as well as, obviously, the first year in baseball history that no pitcher threw at least 100 innings. That won't cut it in 2021, yet, also, most pitchers aren’t tripling their workload.

If you're looking for a precedent, none exists. The last time the Majors had a season that was shorter than 162 games was back in 1994-95, but even that's not particularly useful for us today, because when the '94 season ended in August, a starter like Greg Maddux had already thrown 202 innings. The next year, he threw 209 2/3 innings. Besides, baseball was just a little different three decades ago, anyway.

Needless to say, there's no consensus on what to do, how to approach this. There's not even a consensus on whether it's good or bad, really. It would seem like you wouldn't want, say, Julio Urías to go from 55 innings last year to 180 this year. But is it helpful for someone like 36-year-old Max Scherzer, who had thrown more innings than any other pitcher since he joined Washington in 2015, to have had to make only 12 starts? Is there a bigger benefit in the rest?

It's not hard to find pitchers who think so, like Tyler Glasnow. "I think if anything, from an overall workload, kind of backing off last year could almost be a positive," he told The Athletic. Glasnow threw only 117 combined regular-season innings from 2019-20, but he's being counted upon to be the ace of a Rays staff that's deep, though without Blake Snell and Charlie Morton.

The point is: We don’t know. The only thing we know for sure is that this season will be unlike any other that's come before it, and because this particular problem is so new -- and because the 30 teams have very different levels of talent and depth anyway -- there isn't one established way to approach it. Some teams will start with six-man rotations. Others will use the "piggyback" method. Still others will just move on forward, business as usual. Some teams will have hard innings caps. Some will look more for changes in analytical data. Many will introduce the baseball version of the NBA’s “load management.”

“The idea of a set five-man rotation is not going to be a real thing,” Cubs president of baseball operations Jed Hoyer said. “I just think you’re better off getting your mind around that.”

Right. You think starters and relievers have blended together before? Just wait for 2021, when teams will use any pitching method they can to simply get to that magical number of 1,458 innings. Who is best equipped? To the best of our ability, based on projections and comments and best guesses, we’ve tried to find out where we all stand.

1. What do the projections say?

Let’s go back to that 1,458 total, the number of innings each team is trying to fill. Let’s use the Mets as an example. They’ve had no problem finding extremely high-quality innings over the years, thanks mostly to Jacob deGrom and occasionally others. But they’ve had a huge problem filling in the depth innings behind him, as Mets fans who have seen far too many fill-in starts from the likes of P.J. Conlon, Tyler Pill, Walker Lockett, Tommy Milone, Drew Gagnon and friends could tell you. The best teams have both.

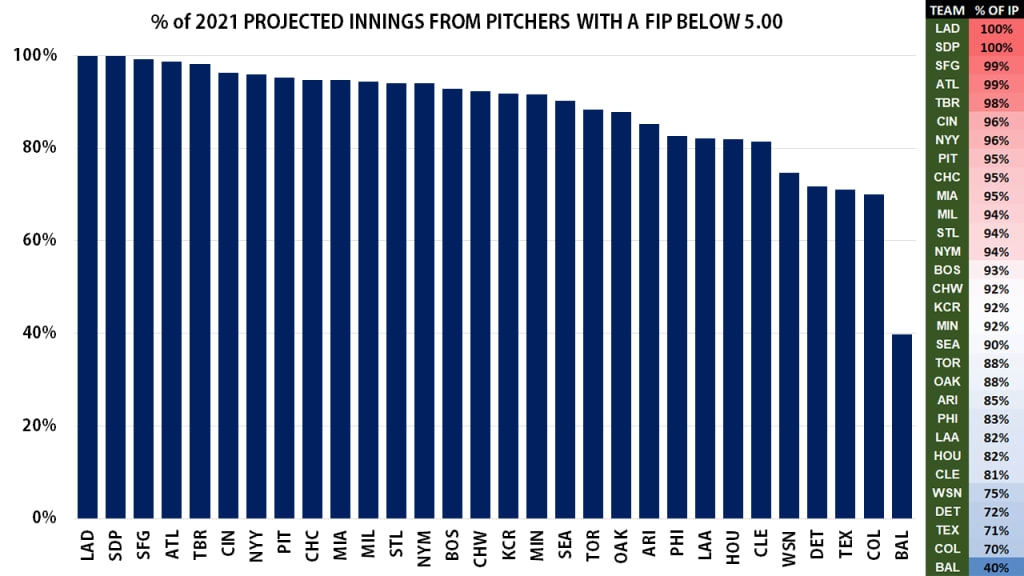

Perhaps, then, maybe the question is less “Who has the most good innings” and it’s more “Who has the fewest bad innings?” There are a million ways to approach this, so we’re going to try to keep it simple. We’re going to look at 2021 projections from the FanGraphs depth charts, which mix Steamer and ZiPs, and we’ll look at Fielding Independent Pitching, or FIP, which is on the ERA scale. We’ll look ahead to 2021 and see how many innings are projected for pitchers with a FIP above and below 5.00. No, having a FIP of, say, 4.98 isn’t “good” exactly, but 5.00 is a decent line to draw to rid us of the noncompetitive innings, like Tanner Roark’s 6.86 FIP last year.

So that’s what we did. We looked at 2021 projected FIP and projected innings for each team. We added up all the innings from pitchers who are projected to have a FIP below 5.00, and then made a chart that shows “What percentage of 1,458 innings are expected to come from competitive pitchers?” It’s fascinating:

You’re stunned to know that the Dodgers, Padres, Braves and Rays are well positioned with pitching depth. (Obviously, someone is going to get hurt or pitch poorly or an unexpected Minor Leaguer will appear; no one is really going to end up at 100% here, but which individual Dodgers pitcher projection can really be disagreed with? If anything, some feel too low.) Teams near the bottom like the Astros, Rockies, Indians and Nationals have a few top-end pitchers, but also considerable depth problems. It’s going to be a long season in Baltimore.

But wait, look to the top: The Reds? The Giants?

It was, really, less than two years ago that we were talking about how the 2019 Reds, in large part due to new pitching coach Derek Johnson, were in the midst of a historic pitching turnaround, and the 2019-20 Reds just had the highest strikeout rate in the NL. They’ve quickly become one of the most respected analytically savvy groups in the game.

You can say a lot of the same things about the Giants, and we did say those things looking at them not long ago. Like the Reds, they’ve quickly become a place where pitchers go to get better, and it’s not just about their pitching-friendly ballpark. We’re not saying those will be the two best pitching staffs in baseball, because they won’t be. But in terms of “having lots of guys who can throw competent innings,” they might be up there.

2. Who has the pitchers who have done it before?

On Tuesday morning, Tigers GM Al Avila spoke to the matter on MLB Network Radio, and he had something really interesting to say.

“Going into this year, [top prospects Casey Mize and Tarik Skubal] didn't get the advantage of building up their innings last year,” Avila said. “As opposed to, say, a veteran guy like Matt Boyd, who, quite frankly, you can pretty much go back to the previous season and look at those innings and be comfortable enough that he can give you the innings you're going to need. The difference is the veteran guys … with the really young guys."

That’s interesting. Boyd threw 185 1/3 innings in 2019, and 60 1/3 innings more last year. Mize and Skubal have 60 1/3 total Major League innings, combined, all from 2020. How much does that matter?

“There’s no data,” Oakland pitching coach Scott Emerson said recently. “Someone would have to really give me some data to support why we should look into guys not throwing as many innings as they did in [2019].”

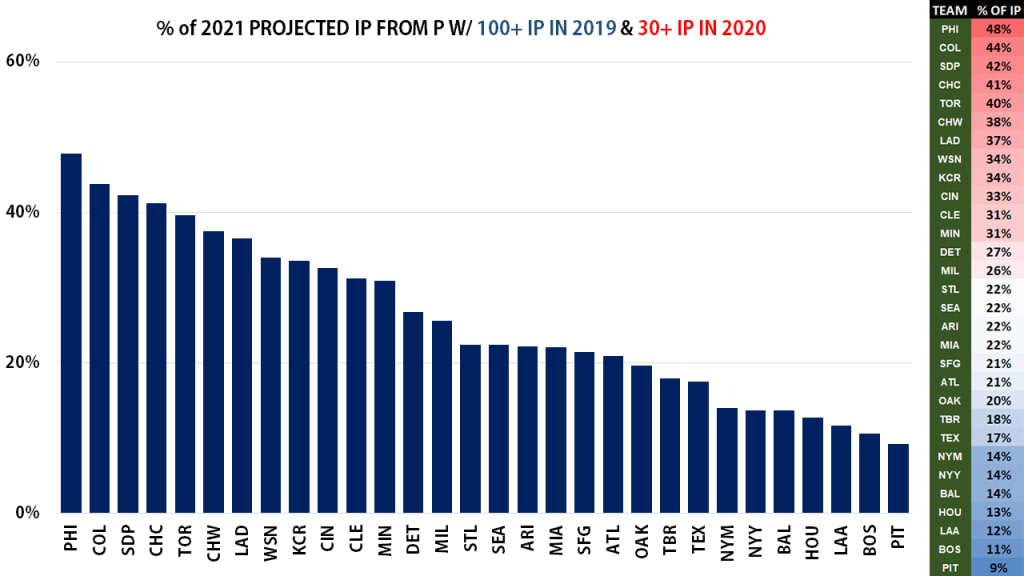

Maybe we ought to look at it like that. Which teams are projected to have the most innings from pitchers who threw at least 100 innings in 2019 and at least 30 in 2020? There were 81 such pitchers, though due to injury (like Dakota Hudson or Mike Clevinger) or departure (like Masahiro Tanaka), not all will be around in 2021.

By that view, it’s good news for the Phillies, who have five pitchers who did that (Aaron Nola, Chase Anderson, Vince Velasquez, Zach Eflin and Zack Wheeler), and more good news for the Padres, who have four of those arms (Yu Darvish, Blake Snell, Joe Musgrove and Chris Paddack), plus plenty of young talent behind them. Of course, all it takes is one injury to one established veteran to ruin the entire idea.

3. What about the pitchers who didn’t pitch in 2020 but still threw?

What this doesn’t do, because it’s all but impossible to account for, is value the work done at the 2020 “alternate sites.” How do we credit younger pitchers who seemingly threw few or zero competitive innings last summer, but instead threw plenty at the alternate sites against competition that was often from a higher level than they'd have faced in real games? We can’t really, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist.

"There were some extra benefits for younger pitchers to be around older players who've been in the big leagues, to face experienced hitters," White Sox farm director Chris Getz said. "The environment also expedited some adjustments. If you're in Arizona or [Class] A ball against lesser competition, you might get away with things that you couldn't get away with at our alternative site."

“It wasn’t like they took a year off,” Oakland’s Emerson said. “These guys were pitching in the summertime whether [or not] it was at their local facilities and throwing.”

Here’s Angels prospect Reid Detmers saying the alternate site “helped me a lot” in his development of a new slider. Here’s Cardinals director of development Gary LaRocque saying that Matthew Liberatore’s time at the alternate site “was a very productive stretch for him -- I couldn’t emphasize that more.” Here’s Reds vice president of player development Shawn Pender saying “all of [Hunter Greene’s] pitches improved” at the site; on, and on, and on.

“I think we’re stuck in this thing of not giving due credit to what those guys did last year,” Royals manager Mike Matheny told the Kansas City Star. “I’ve watched some of these players improve from 365 days ago. How much they’ve improved, you normally would not see that had they played every day of a typical Minor League season. What they were doing was everyday baseball.”

He’s right. We can’t quantify it, because how could you, really? It’s just another aspect of baseball’s most difficult year that’s going to have unseen impacts on the year to come.

4. What are the different strategies we’re seeing?

“It's a delicate process, and it takes some planning from start to finish,” noted Miami pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre Jr.

Not everyone has the same plan, though. Here, to the best we’re able to tell, is how the 30 teams are approaching it.

The six-man rotations

• Angels

• Mariners

• Pirates

The Angels might have gone to a six-man rotation anyway given the special situation of Shohei Ohtani, really; he’ll be joined by Andrew Heaney, Dylan Bundy, Alex Cobb, Griffin Canning and José Quintana. Mariners GM Jerry Dipoto appreciates the extra time between starts for “pitch development and pitch shaping,” because as he told MLB.com, “we feel like that’s a huge advantage for such a young staff.” After signing Trevor Cahill earlier this month, it seemed quite possible the Pirates would go with a six-man rotation, though GM Ben Cherington hasn't quite fully committed to it yet.

The four-man rotations, to start

Wait, four? We’re talking about teams needing more starters than ever, and these clubs are going the other way?

• Indians

• Royals

Thank the schedule. The Royals, for example, have three scheduled days off in the first nine days of the season; they’ll likely start with four starters before going to five or possibly six.

In Cleveland, “the Indians are looking to utilize a four-man rotation for at least the month of April because they have five off-days,” wrote MLB.com’s Mandy Bell this week. Shane Bieber, Zach Plesac and Aaron Civale will be the top three, and it’s not yet clear whether Triston McKenzie, Cal Quantrill or Logan Allen will be the fourth; all will likely start at some point.

The piggybackers

• Dodgers

• Rangers

• Tigers

This one is difficult to categorize ahead of time, but some teams have been pretty open about the fact that they’ll have some “regular” starters and also some games where two pitchers are each expected to go multiple innings. The Rangers, for example, are thinking of it as a seven-man rotation where Kyle Gibson, Kohei Arihara and Mike Foltynewicz are “traditional” starters, and pitchers like Dane Dunning, Kyle Cody, Taylor Hearn and Hyeon-Jong Yang tandem for the others.

“That is also something we will use most assuredly this year,” Avila said about his Tigers. Meanwhile, the Dodgers will clearly let Clayton Kershaw, Walker Buehler and Trevor Bauer run, but we’ve already seen them use the tandem strategy with Dustin May, Tony Gonsolin and Urías, plus there are options in how Jimmy Nelson and David Price get used.

We’re likely underselling how often this gets used by other teams.

The “what even is a starter anyway?”

• Orioles

• Rays

Even in the best of times, the Rays rely on openers and bullpen games more than most, and now they’re going at it without Snell or Morton. They’ll push Glasnow and Ryan Yarbrough as much as they can, and then throw endless amounts of Rich Hill, Chris Archer, Michael Wacha, Joe Ryan, Josh Fleming, Shane McClanahan, Luis Patiño, Collin McHugh, and on and on and on as needed.

The Orioles have the opposite problem, which is that they simply do not have enough Major League-quality pitching. We’re more optimistic on John Means than most, but manager Brandon Hyde is going to have a difficult time filling out 162 games' worth of pitching.

The revolving five-man rotation

• A’s

• Astros

• Braves

• Brewers

• Cardinals

• Giants

• Marlins

• Mets

• Padres

• Yankees

These clubs will start off with five starters, but it’s already pretty obvious that what you see now is not what you’ll get for long.

The Braves will start with Charlie Morton, Max Fried, Ian Anderson and Drew Smyly, then slot in someone like Bryse Wilson, Kyle Wright, Huascar Ynoa or Touki Toussaint when a fifth starter is necessary, and then it’s all going to change anyway when Mike Soroka can return in another month or so. Miami has a talented but young rotation, so to avoid end-of-season shutdowns -- “I personally feel like it's important that they pitch in the month of September,” Stottlemyre said -- there are likely to be skipped starts here and there.

Houston’s Dusty Baker doesn’t want to use a tandem strategy or a six-man rotation, but Framber Valdez’s injury and Jake Odorizzi’s late addition will force him to get creative. The Cardinals, too, have dealt with spring rotation issues, leaving plenty of questions behind Jack Flaherty and Adam Wainwright. The Mets are similar, knowing they’ll start without Carlos Carrasco and can expect Noah Syndergaard later on.

“We’ve always thought about five guys traditional with six guys options,” said Oakland's Emerson, and veteran Mike Fiers is likely to be that sixth man -- replacing someone, not adding to -- when he returns from a sore hip.

“I think most times this year, you will see us stick to five,” said Brewers manager Craig Counsell, though he later gave the game away, saying, when asked if Josh Lindblom or Freddy Peralta would win the No. 5 spot, that “no matter what we decide there, I would assure that by the end of April, [both are] starting games.”

Meanwhile, the Padres will start without Dinelson Lamet in their rotation, expecting that he’ll then join the group early in the season. Ditto for the Yankees, who can’t really count on anyone past Gerrit Cole, may end up giving starts to each of presumptive “fifth starters” Domingo Germán and Deivi García, and will later welcome back Luis Severino.

The traditional five-man, for as long as it lasts

It won’t last all year, obviously. Each team knows that. But these clubs appear to be content to go with a traditional five until circumstances force them to do something else. (Which, of course, they will.)

• Blue Jays

• Cubs

• D-backs

• Nationals

• Phillies

• Reds

• Red Sox

• Rockies

• Twins

• White Sox

“We haven’t talked about anything more than a five-man,” D-backs manager Torey Lovullo said, and the five names were clear enough, though that was before news came that ace Zac Gallen was injured. “No six-man rotation yet,” said Cubs manager David Ross early in camp. “If you do go that route, you're short in the bullpen a guy.” While Hoyer was clear there won’t be a set five-man rotation, he’s likely just reading the tea leaves for later on. Meanwhile, the injury-stricken Blue Jays would like to let Hyun Jin Ryu, Robbie Ray, Steven Matz, Tanner Roark and Ross Stripling go for as long as they can before needing to dip into their reserves.

Minnesota’s had a different spring, in that all five of its starters -- Kenta Maeda, José Berríos, Michael Pineda, Matt Shoemaker and J.A. Happ -- have been healthy, and Randy Dobnak (with his new slider) and Lewis Thorpe have been impressive. Again, there’s no reason to think this quintet stays whole all year, but they might also just let them ride until they have to do something else. It's a nice problem to have.

The Nationals are likely to attempt one of the more traditional five-man rotations in the game, though the age of this group makes it very unlikely they'll all stay whole; say the same for Boston and its rotation of arms with recent health problems. Still, that’s a baseball issue, not a pandemic issue. The Rockies, White Sox and Phillies fit here, too.

There’s not one right way to do this. There might not be a right way.

“The way we generally look at that is we don't have hard and fast rules or place blanket policies on players,” Cleveland president of baseball operations Chris Antonetti said. “What we try to do is think about each player as an individual and what positions them to be healthy and successful.”

"You really have to look at it on an individual basis, day to day,” noted Avila.

That's exactly right. It's all you can do. Baseball, for years, had been trending away from the traditional starter/reliever relationship anyway. After what happened in 2020, you can expect '21 to exacerbate that movement. It's going to be unlike anything you've ever seen before.